The sentences below have become a popular

I am a poet and I don’t know much about Pi. But if all information that has ever existed can be found in it, then the volumes of work that math artist John Sims has produced must be Pi incarnate.

I first met John Sims in 2010 when he was curating a year long Art Wall at the Bowery Poetry Club in New York City. He was looking for poets who wanted to collaborate conceptually with artists who integrated math into their work. I soon realized that this was no simple collaboration—this was an invitation to become a part of John’s vastly complex and ever-replicating worldview, one that brings math into forms of civil and political works of art that expose the very matrix that power and injustice create in the world. And most importantly, Sims’ work shows how to change it.

Sims has collaborated with hundreds of artists, writers, mathematicians, teachers, social activists, neighbors, and curators; his work has appeared in museums, social clubs, neighborhood blocks, and poetry readings—he is fearless in the way he moves through and integrates diverse worlds, dissipating any notion of separation between human beings and their potential to understand math and art. Math is a unifying principle and art is infinite in its potential to create forms and shapes—and this is Sims’ field of inquiry, urgency, and play. His expansive sense of generosity is as infinite as is his energy.

John and I had the following conversation on Google Docs—often we were writing and editing at the same time, and seeing the trace of each other’s thought process made it seem as if we were sitting right across from each other in a cafe.

–Kristin Prevallet for Guernica Daily

Guernica: John, you are an artist for whom boundaries between conceptual ideas, performance, political urgencies, aesthetic beauty, community, and viewer participation do not exist. Your work moves between multiple worlds with a seeming ease, as if forms do not sit still for you. You’re a math artist, and yet, politics seems to be the spine in the body of your work. Math seems so purely conceptual—how do you think about the connection between math and politics?

While much of my work is generative and redesigned, it’s really about the stimulating shift in the structure of the emotional space—that raw space that frames one’s political expression.

John Sims: I think politics, especially visual politics, is a main artery of my work. I usually start with an object of design, as metaphor, as a portal to a deep conversation and exploration about issues and themes of justice, supremacy or simply of beauty or the convergence with unmitigated excitement. Much of my work is about colliding opposites and congregating the counter-intuitive, pushing for a space of political experimentation. And while much of my work is generative and redesigned, it’s really about the stimulating shift in the structure of the emotional space—that raw space that frames one’s political expression.

Guernica: The confederate flag project seems to be a really clear example of this. You recolored that flag, turned it around, stripped it of its brutal symbolism and replaced it with symbols of unity, collectivity, beauty, and people coming together in spite of difference. And then, you burned the old symbolism in public rituals, which I’ve got to say is a bit of a shaman move…definitely all about exposing raw spaces and the emotional expression that occupies them. But what about Math? How does math get to that emotional rawness, that ability that you have to reframe the very frames that this culture seems to hang onto with such hurtful consequences? Because if it can do all that, I wish I had paid more attention to it in school!

John Sims: First, it is interesting that you mentioned the “shaman move“ because I’m a big fan of Joseph Beuys, who is often referred to as an artist and shaman. His work, which traversed the performative to the pedagogical to the social anthropological, invites one to explore unsuspecting raw spaces for emotional, psychological and political examination.

Guernica: Beuys makes a lot of sense as a source of inspiration for you. He believed that the artist is one who sees symbols (i.e. the confederate flag) as forms that are always in flux. And the emotional attachment to symbols must be transmuted in the same way. Do you see mathematics as an emotional field within the infinite permutation of forms?

John Sims: There is structure to these particular types of forms. And perhaps part of my motivation here is to find the right mathematical language and process to best conceptualize and map these forms from one space to another. For instance, in the installation Square Root of Love, which I did with Karen Finley, I sought to explore the relational nature of love using the language of algebra. In another installation, inspired by the topology of the Hangman’s noose, I looked at all the unique knots up to eight crossings, and presented them as a rope installation. The mathematics allowed me to see beyond the retinal and the political and emotional context into a space where symbols as form can run naked waiting to be re-dressed.

Guernica: One thing I really admire about how you work is how your artistic vision is so often collaborative…you are a curator as well as an artist.

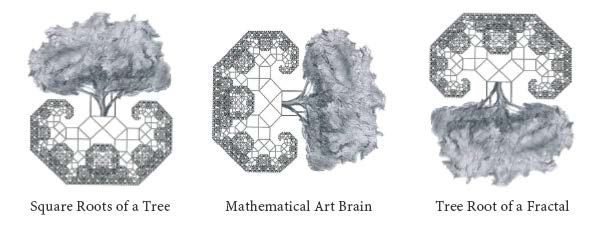

John Sims: Absolutely. Working with the collaborators in mathematics and art adds more voice to these conversations. One of my favorite examples of this is when I was the Coordinator of Mathematics at the Ringling College of Art and Design, where I co-curated with Kevin Dean a show called MathArt/ArtMath. This was inspired by my Square Root of a Tree graphic series, which I think explains my process the best.

Anyway, that show featured a range of about forty-five artists, including MC Escher, Sol LeWitt, Howardena Pindell and fashion designer Jhane Barnes. Curating this show enabled us to push beyond the politics of segregated curriculums, public confusion on the subject, and stuffy classrooms. The curating became another way to organize, protest and challenge.

Guernica: One of the concepts you brought into form that I really love is the “Cartesian Hive.” It seemed to be your metaphor for how you draw people together into a network, and how each person’s work can come into relation with each other through the intersections of math, art, politics, and symbolic logic. You expanded the hive to include poets, and ended up bringing a bunch of us together into what you called a “Rhythm of Structure: Mathematics, Art and Poetic Reflection.” You had an art wall for an entire year at the Bowery Poetry Club, it was awesome!

The aim of the show was to present mathematics, not as a servant of science, but as an enabler of the arts

John Sims: That show featured nine exhibitions, a catalog, and a documentary of over seventy-five artists and poets including Sol LeWitt, Adrian Piper, Karen Finley, DJ Spooky, Dread Scott, Dorothea Rockburne, Mark Strand, Bob Holman and you. It featured collaborations with both a high school art class and a graduate class at NYU. The range was very dynamic. The Cartesian Hive piece (my favorite) was created around the Square Root of a Tree graphic and is inspired by my quilt work. But my big favorite was in fact the cover image of the catalog which, like the exhibition, was designed like a nine patch quilt.

Guernica: Right—one inspiration leads to another leads to another leads to another, into infinity! Where does it go from there?

John Sims: Well, that show prepared me for Square Roots: A Quilted Manifesto, featuring music, poetry, video art, Pi dresses and thirteen mathart quilts, which I did with Amish quilters. The aim of the show was to present mathematics, not as a servant of science, but as an enabler of the arts and also to engage a wider discussion of the importance of mathematical literacy as a political necessity to navigate in a world with so much data and visual deception.

When you add the context of demographic issues, curriculum politics, classroom tracking, supremacy, and IQ testing, we see that there is an unspoken war between Art and Mathematics.

Guernica: Yes—your Seeing Pi Quilt definitely has a pedagogical aspect to it. I remember that when I first saw it at Dorsky Galley in Queens, NY, I understood Pi in a brand new way—ideas about recursiveness and replications into infinity really do make the world seem more alive in its possible futures, rather than its stuck past.

John Sims: I was motivated to do this Quilt project because I wanted to get my students excited and inspired. Because I see how much emotional pain mathematics and its instruction induces in the average person and certain underrepresented groups, like artists. When you add the context of demographic issues, curriculum politics, classroom tracking, supremacy, and IQ testing, we see that there is an unspoken war between Art and Mathematics.

Guernica: Math becomes torture for so many kids and that really does seem unnecessary.

John Sims: And yet, mathematics literacy and mastery is very important in identity formation in terms of cultural access. This is why its instruction is crucial. And when you look at The Algebra Project by Bob Moses (mathematics educator and veteran Civil Rights Activist), you see quite quickly how critical mathematics education is for extended social justice activism.

Guernica: Now I am beginning to understand your Recoloration Proclamation series of projects. Abraham Lincoln’s “Emancipation Proclamation” poetically states: “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” But that phrase, “forever free” has lots of strings attached because the country never really achieved color blindness. And consequently, color continues to matter and inhibits African Americans from their designated and rightfully earned freedom. How does math work within the consequences of this history?

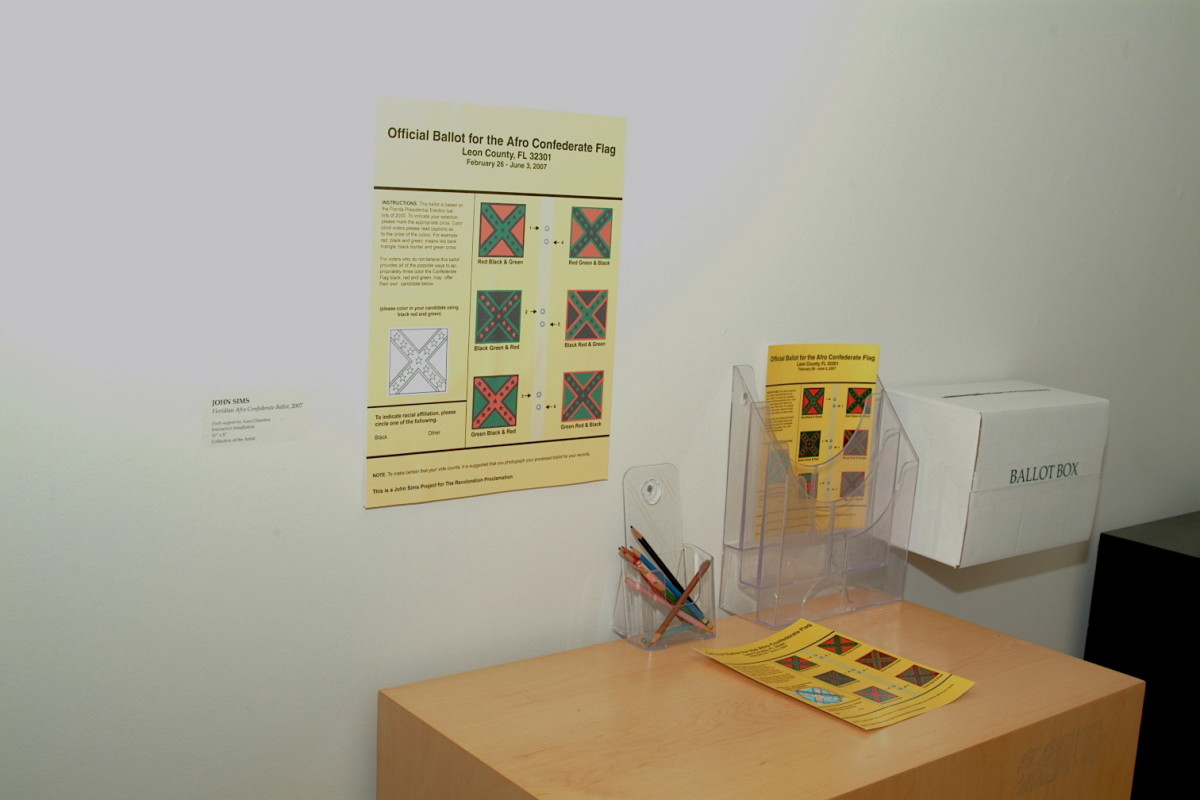

John Sims: The genesis of this recoloring was certainly shaped by my mathart dialectic—I find the visual average and combinatorial possibilities between opposite sides of struggle to be very stimulating, and this is where the real action is. Hence my mathart brain and AfroConfederate Flag definitely come from the same place of thinking.

I think flags and colors can be strongly connected to identity, especially of a group. So recoloring the Confederate flag red, black and green (the colors of black nationalism) was a way to protest the ethnic and historical cleansing promoted by the Southern Heritage movement. That creative protest became a “visual sit in” and an Occupy Flag gesture to make the statement that Black history, culture, and trauma matter, especially when talking about the Civil War.

First, I showed a recolored flag in a Soho Gallery, then took the show to Harlem, and then to Gettysburg, where I introduced my Proper Way to Hang a Confederate Flag installation—the flag hanging from a noose. Things got really crazy and political . All of this will be in my forthcoming documentary.

Then after the Gettysburg Drama I had an exhibition at the Brogan Museum in Tallahassee, FL, where I redesigned the 2000 Florida hanging chad ballot and created a voting station where people could choose among six combination versions of red, black and green Confederate flags. This revoting on the recolored Confederate flags speaks to the freedom to protest and the freedom to assert one’s voice in unjust spaces.

I then made a recolored bumper sticker, and this lead to my Recoloration Proclamation, a fifteen year project that includes over twenty flags, a gallows installation, video work, a play, a film and the AfroDixie remixes. This project made me I feel like I was George Washington Carver grinding away on my flag peanut. But moving the work beyond the art space into the media and traditional spaces is sometimes where the real work and engagement needs to happen. So the work has gone from Soho to Harlem to Gettysburg to Tallahassee to a KKK gallery in St. Petersburg. And I ended up recoloring other flags too—moving beyond the rebel flag.

Guernica: A KKK Gallery in St Petersburg? What on earth is that and how was your work received there?

John Sims: That was a trip. I was passing out AfroConfederate bumper stickers with my math students. The Klan folks seem to be harmless. It was the snipers on the rooftops that were scary….

Guernica: John, you are fearless. You walk into these situations that could provoke reactions of violence and hatred, and you diffuse it. Are there other examples where you have confronted social violence in this way?

John Sims: In 2015, I was in Baltimore two days after the Baltimore drama. I was there for a group show called Evidence: Identity Through Fiber at the Creative Alliance where I presented a wall installation called Journey of the Political math artist, featuring the flags, quilts and the rope piece.

This show was critical for me, because two things happened: one, I (this self-proclaimed political math artist) quickly responded to the Baltimore situation. After seeing the Baltimore flag and its geometric structure, I redesigned it red, black and green. Within a couple of days, I found someone to make two different physical versions of it in time for the opening. I must say, it felt good to see the mathart collaborating with the political art in a historical moment.

The second thing that happened was after walking around Baltimore under curfew, attending various galleries and visiting the epicenter of the riots, I knew the time was right to finish what I started in Gettysburg: bury the Confederate flag.

On Memorial Day a few months later and in honor of the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, I organized thirteen Flag Funerals. This was a simultaneous burial and cremation of the Confederate Flag in each of the states indicted by the stars in the flag. From each of the thirteen teams, a poet contributed to the poetic medley:

This all happened three weeks before the Charleston Church Shootings, which unfortunately is what lead to the removal of the Confederate flag from the state grounds in South Carolina.

Guernica: It’s incredible that you buried the flag and then that tragedy happened. Clearly a lot of different and opposing energies are at play around that flag, and you’re bringing it into a space of mourning, which is what it is now and always has been. I also had the privilege of participating in a Dixie Remix Listing Party that you hosted at the Bowery Poetry Club in New York City, and you spoke there about how difficult it is to know that art can have transformative power, if only people would pay attention to it. It almost seemed as if you felt that the project and all of the poets who came forward with their eulogies could have stopped those murders from happening. It was a really powerful evening listening to the thirteen shifting forms of Dixie within the context of all the racial violence that is happening. Is music for you another kind of mathematics?

John Sims: In all of my projects I have a music element, but music is a very important way to engage the emotional space. In some ways, the AfroDixieRemixes is the audio version of the AfroConfederate flag work. To take this socially complicated song and have it redone in thirteen different black musical styles over thirteen years with local musicians was a great experience. After you listen to the Gospel version of Dixie you never hear that song again the same way.

Now I am taking the music on the road with these listening parties around the country where I am inviting poets and writers to respond to the AfroDixies. I think the poetic voice is so important and in some ways I see it as emotional mathematics, where individual expression is a portal to universals. And so I am very grateful to work with poets like you. More work to do. Now I’m trying to wrap it up into the Recoloration Proclamation documentary film project.

Guernica: What does your studio look like at this moment?

John Sims: My studio, sometimes an extension of my studio brain space, is set up at the moment to seduce thinking and mental reflection—a sort of concept laboratory and presentation space for my friends, art colleagues, potential patrons and collectors. I have art, books, and musical instruments everywhere. A big white square work table to sort out ideas and draw schematics for things to come—space to properly interrogate fresh ideas before they’re introduced for multi-media wardrobing. The space is organized in a Bauhaus sort of way but comfy like a New England cottage and three blocks from the Gulf of Mexico. But another question here, is what does the space feel like. Well, it makes me feel like thinking and working. Being me is the journey through mind, hand, and heart by way of mathematics, art and politics.

Guernica: Well John, this interview is being conducted in honor of Pi Day. I would assume that every day is Pi day for you because your work seems to be composed by the very energy of Pi itself, whether directly or indirectly. Do you celebrate Pi Day? A big party or anything like that? It seems a lot more fun than the fourth of July, that’s for sure!

John Sims: In 2015 we celebrated the Pi Day of the Century: 3/14/15. For that I created the Pi Day Anthem featuring the mathmusician and internet sensation Vi Hart.

So here I am for the celebration of Pi Day—March 14—as a way to continue to expand the conversation around connecting mathematics to nature and the arts. But it’s also a place to start demystifying mathematics and putting it into a cultural context.

Guernica: You never stop do you? The forms keep on evolving and growing and intersecting with ever expanding hives of people and concepts. You’re like the center of a mandala that expands infinitely, symbolically guiding us through the abstractions of math and art to the essence of reality. Do you think about your work spiritually in this way?

John Sims: In some sense I am drawn in by long-term big battles whether they are the socio-politics of Mathematics vs. Art, or the ongoing fight over the symbols of the Civil War. I plan to present these intersecting battle narratives in my current book project, Journey of the Political Math Artist. So there is a place where politics through the pursuit of social justice becomes a spiritual journey.