“My Monticello,” the anchoring novella in Jocelyn Nicole Johnson’s debut collection, follows Da’Naisha Love, a young Black woman born and raised in Virginia, through a near-future world of environmental and social collapse. Cell phones no longer work; gas and electricity are unavailable; mobs of racists have taken over. Love leads a diverse group of neighbors fleeing a violent white militia to find refuge in Jefferson’s home and plantation, Monticello, where she once worked. Da’Naisha Love is also connected to Monticello in another way: she is a descendent of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson, as is the ailing grandmother Love watches and worries over. The makeshift refugee community becomes a family, staking their claim over the land, their history, and their future, ultimately leaving room for love and hope.

Johnson’s collection explores the deep connections between our nation’s legacy of white supremacy and the climate crisis in which we now find ourselves. Her stories play out the consequences — foreseen or not — of a past unexamined and unreconciled. My Monticello is a formidable book that bears witness to this country’s legacies and tackles the most intractable and urgent issues of our time with originality, vision, and a rare warmth and humanity.

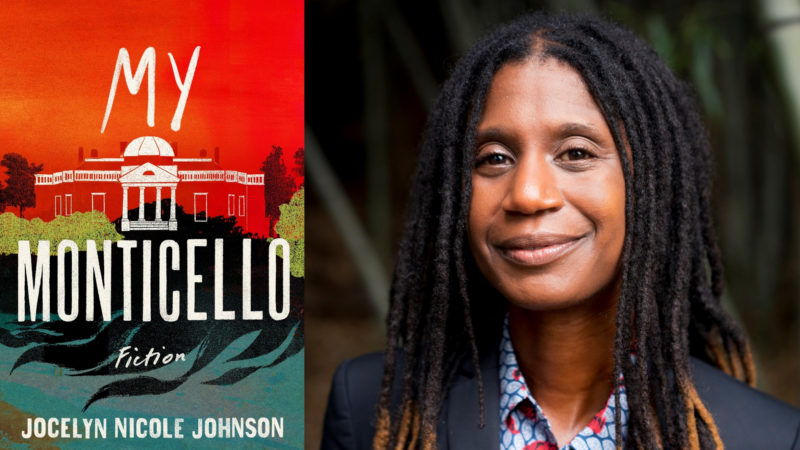

This combination of qualities may well be the product of wisdom and experience accumulated over time: Johnson has lived and worked in Charlottesville, Virginia for over twenty years, teaching art to public school elementary students. She recently described herself as a “50-year-old literary debutant,” with the publication of her much-anticipated debut collection, and the announcement of a deal with Netflix. One might also argue that it took time for the literary world to catch up to Johnson and her extraordinarily timely stories, all uncannily prescient in evoking how a warming planet and unrestrained racism combine to bring existential dread to a fever pitch.

This interview is a sort of homecoming for Johnson, whose first published short story “Control Negro” appeared in Guernica after our editors read it in the slush. “Control Negro” went on to be chosen by Roxane Gay for the Best American Short Stories 2018 and read on radio by LeVar Burton as part of PRI’s Selected Shorts series, and is included in the new collection. I spoke with Johnson from her home in Charlottesville.

—Elaine H. Kim for Guernica

Guernica: Tell us about the origin of “My Monticello,” the titular story in your collection. What were the seeds, and how did it bloom in the way that it did?

Jocelyn Nicole Johnson: The collection grew out of twenty years of living in Charlottesville, Virginia — in particular, the last few years after the Unite the Right rally here on August 12, 2017. After white nationalists descended on our town, displaying a very specific brand of violence and vitriol towards Black and brown Americans, there were a lot of opportunities to learn about the local history of racism, going all the way back to the founding fathers. Here in Charlottesville, that’s Thomas Jefferson — Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation home, is right on the hill, a few miles from town and about ten minutes from my house. I went to a local event and, at the end, a descendant of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson — a Black woman — was introduced to the audience. I saw her in town later, doing something mundane like pumping gas, and I was like, Wow, she lives here. Something connected for me seeing her physical being, seeing her here, so close to Monticello and that history. That was the spark for me.

And then came the basic elements of the novella: a group of neighbors who live in Charlottesville, in a near-future time of environmental and social unraveling, experience an exaggerated version of August 12, 2017, where they’re forced from their homes and have to flee. They go up to Monticello. The person who would tell the story was a young Black descendant of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings. I had those pieces, but did a lot of filling in, learning about Monticello and figuring out what could be believable to a reader. I certainly thought a lot more than I ever had about Thomas Jefferson and the stories told about him.

Guernica: Can you talk more about Da’Naisha Love? How and why is it that she’s the one to lead this group in this moment, and to this place, Monticello?

Johnson: Living in Charlottesville, the stories you hear about Monticello have changed a lot, but they certainly didn’t center someone like this protagonist: Da’Naisha Love, a young Black woman who grew up in Charlottesville, who goes to the University of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson’s premier university that sits in the middle of town and takes up so much space. What would it mean if you went to Monticello and those stories had been centered on someone like Da’Naisha? I think I would have experienced a certain amount of energy in that, a certain amount of wonder and validation. And I love this idea not only of Da’Naisha and her grandmother, who were direct descendants, but also of this diverse group of neighbors being able to go into that house and feel that it was meaningful to them personally, to be able to touch all the things — not with malice, but with some of that preciousness removed. Having them all be able to touch and use history, and through those objects think about the whole situation in a different way. For me as a Black woman, a Black American, there’s this extra layer of this isn’t yours that gets conveyed both explicitly and implicitly. I really wanted it to be the opposite for Da’Naisha and for this community in the novella.

Guernica: Exemplifying that opposite is the phrase “We Are Here,” which shows up a number of times in the novella, in different contexts. The phrase first appears as giant letters signaling for help; then the main character, Da’Naisha, shouts it to interrupt a burgeoning conflict. Finally, Da’Naisha whispers those same words in comfort. Why this phrase, again and again?

Johnson: Those words were definitely important to me, in the sense that Da’Naisha and the group’s existence is enough — they don’t have to be extraordinary. They don’t have to be perfect people, and they certainly aren’t. They don’t have to prove their worth; their existence and their humanity inside Monticello is enough. Those words are kind of an announcement that anything might happen — and that’s kind of all they have. There’s something wonderful about being acknowledged, and about acknowledging a moment you’re in, both for yourself but also for the future. There’s this idea in history of who is marked, who is on the list, whose name is there. Who is remembered. I think all those ideas are in that phrase.

Guernica: In many of the stories in this collection, and certainly in the novella, the characters — mostly Black, living in the South — are living in and/or aware of climate disaster. There’s often a looming sense (or explicit reality) of existential dread. What’s this juxtaposition about for you?

Johnson: I think that’s just me as a human being. As a Black Southern woman, I’m full of dread. And I think, in this weird way, writing the dread out, speaking it, and giving it to characters — and then giving it to readers — was a bit of an exorcism in that. It made me think, Well, if I share this with other people, if I say now this is true and this is an issue and also these feelings are real, then they could share them with me and I wouldn’t have to feel like I had to fix it alone. There are big systems that need attending to, and these big environmental and social and structural systems are frayed. But we’re also negotiating the day-to-day things — some of them so important, like caring for our children, and some of them superficial, like thinking about what clothes to wear or buying things that we don’t really need to distract and soothe ourselves to get by. How do we do all these things at once?

Guernica: One of the fascinating things about your work is how you tie in our history and legacy of slavery with the gradual destruction of the earth. Can you talk about this a little bit?

Johnson: I think how we do anything is how we do everything. The way America does racism is very connected to the way America does capitalism and colonialism, and is connected to what we value and the stories that we tell ourselves. In America, it’s often about every person for themselves and the valorization of a certain kind of freedom — where your freedom can entirely infringe on someone else’s and even destroy them without penalty, particularly if you look and sound a certain way. I think that racism and the climate crisis are connected in that way. I also think that one exacerbates the other: environmental issues exacerbate racism, or are filtered through the lens of racism, in obvious ways like where a refinery is placed or where pollution ends up or, when there’s a storm, which neighborhoods have protection or where investment goes.

Black and brown people experience not only devastation at the end of climate change, but also more subtle deprivations: a loss of shade trees and the inability to go out into nature for rejuvenation. I think there is a mythology that Black and brown people don’t care about nature or the environment, and I don’t think that’s true. It certainly isn’t true for me. This is another simplified story that isn’t the whole story; it isn’t the story at all. I think it serves those who benefit from climate change. It’s another way to quiet or discount a group of people.

Guernica: The community built in “My Monticello” is intergenerational, from the very old and dying to the yet-to-be-born. It’s also very diverse — racially, ethnically, and in terms of national origin. What were you thinking about as you built this group, which grows over the course of the story? What was important to you about creating this community?

Johnson: I’ve been a public school art teacher for many years, so that is my bread and butter: a bunch of people who are different and don’t really want to be in the same room, but are. They live in the same neighborhoods and are forced to create a community. Teachers are tasked with creating the conditions for that community to happen, and the very best teachers do it really, really well. I believe in those public spaces and the opportunities they present; they might be the only time you come together with a bunch of people you don’t necessarily want to be with. So I played with that: Da’Naisha is studying to be a teacher, and I used a lot of the things teachers do to create community. Her way of bringing the group together is this kind of hasty constitution, which is a very first-week thing to do as a public school teacher, generating a list of intentions and what our community is going to do together.

I also based the neighborhood in the novella on First Street, which is right near my home. It’s very diverse and includes a cluster of public housing. In the story the characters are mostly fleeing from public housing. There are people from all over, who immigrated to the United States from all over the world. There are people of all colors, people of all ages, people of all ways of being in that space. I wanted the neighborhood in the book to have that quality as well, as I believe in the possibility of placing a lot of different people together and then finding some commonality.

Guernica: You skirt an edge, particularly in “Control Negro” and “My Monticello,” between the present and a very near future, where what’s come to pass feels both unthinkable and also completely, frighteningly possible. We also see, in “My Monticello,” glimpses of what has occurred, including the Unite the Right rally and the murder of Heather Heyer. Can you talk about these gestures and the connections you make between our current reality and an imagined near future?

Johnson: Books come out so long after you’ve written them. When I first wrote “My Monticello,” it was maybe a year out from August 12, 2017 and a lot of things hadn’t happened yet. There hadn’t been the storming of the Capitol. This very concerted assault on democracy hadn’t been waged yet. The [2020] election hadn’t yet taken place. I had imagined the novella would be more fantastical than it actually became — even the way that storms and weather have changed in a short time since then seems dramatic, not to mention the global pandemic. In a way, we’ve become closer to some of the predicaments in the story.

But when I wrote it, I thought of the story as a kind of warning to myself, a series of questions. What happens if our situation continues unaddressed? What happens if we don’t address environmental and social issues, or even just infrastructure problems in general — what could happen, and what might that look like, and how can we talk about not just the future but how our present relates to what’s happened in the past? There’s so much nostalgia for the past, and I thought, Well, what if that nostalgia gained energy and came to fruition? What if it unfolded right now? Because that past is also about America’s brutality towards Black people — what would that look like, what forces would underpin that alternate reality to make it come to life?

I think there’s a way we can look away, distract ourselves. We can go buy something on Amazon, we can close ourselves off, and I wanted to immerse myself in those questions as a way to keep myself present and awake and hopefully make choices with care and hope. And not hope because “everything’s going to be better” — there are much smarter people than me who’ve been working on all these things tirelessly, and they’re not easy problems — but I think every moment we’re awake to reality is an opportunity to inch towards something a little bit better. If it can inch towards horrible, it can inch towards slightly better; we can alleviate and ameliorate and find kindness and find community and care for one another.

Guernica: In many ways, the subject matter your stories and characters explore are both the most intractable and the most urgent issues of our time. Given this, where would you say your work — and your characters — land on the spectrum of hope and despair?

Johnson: I absolutely love all my characters, even the hard-to-love people. I think that’s why I’m a public school teacher: I kind of love the person who’s a mess, and I love the person who is difficult. They’re all doing the best they can, even when they’re doing things I really wish they wouldn’t do; I hope that comes through. Some of the predicaments are bleak, but I don’t think the characters are. They all want something; they all want to be cared on; they all love or care about someone, or long for something. And I hope readers identify with that.

I often think about how a story force like QAnon can make people do things that don’t make sense to me and are harmful — but then there could also be a force that could make people do things that are wonderful and helpful and restorative. There could be a story we tell ourselves that would help us undo the harm that has been done. We’re so motivated by community and story. I think about that all the time, how that is a possibility. And I also think that, no matter what, we can still do good. Even if we can’t fix everything, we can fix something. We can start.