All images courtesy of Greg Reynolds and Bywater Bros. Editions

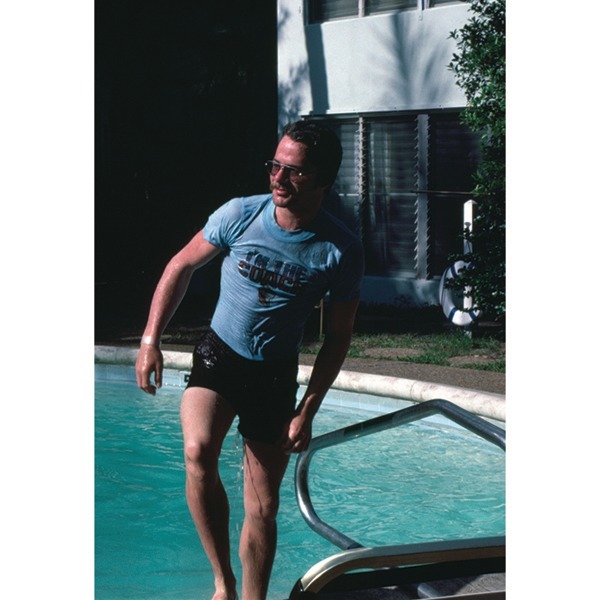

In his new book, Jesus Days, 1978-1983, photographer Greg Reynolds presents a fragment of his past, a time of personal repression: the denial of his homosexuality. Born into a Southern Baptist family in Kentucky, Reynolds joined the evangelical InterVarsity Christian Fellowship as soon as he left college, entering a world that prohibited drink, drugs, or sex before marriage. He became a dedicated youth minister, conducting Bible sessions and supporting young Christians at home and on mission. One summer, he was given a Pentax K1000, a 35 mm, single-lens camera. Without any prior training, he captured casual images of his friends, family, and work. A few years later, he went into therapy, came out, left the religion, and moved to New York to study film at Columbia, closing the door on that part of his life.

Decades later, Reynolds found the box of dusty Kodachromes at his parent’s house. Something compelled him to look at them. “There’s a bit of theater in looking at slides,” he explained during a recent phone interview. “Until you put the carousel into the slide projector and throw those things up on the wall, you don’t really see them.” The images revealed themselves to him gradually. His natural talent for composition and beauty is striking, and his connection to his subjects is straightforward and true—there is no self-conscious vanity, or Instagram aesthetic. Also unmistakeable are Reynolds’s hidden longings. The camera singles out his male contemporaries with understated eroticism, while his women friends radiate warmth and friendship. He was in love with his best friend, and not with his girlfriend, whom he felt he should marry. Yet his gaze is untroubled by his secret. “It wasn’t a miserable life,” he said. “Miserable would be not being fully yourself, hiding yourself, but it was a loving community, with friends and people you cared about.”

Reynolds was intimidated by the artistic life, and could not see himself in it. The organization helped him deflect and avoid. “There’s this conflict that you can be in: not the right situation, but at the same time, you can feel safe and secure in it,” he said. “I felt protected. I didn’t have to deal with sexual feelings, I didn’t have to put myself in a position where I would feel afraid.” He found a therapist who, while Christian, had no agenda to turn him straight. “I came to grips with my being gay, recognizing it, and accepting it. That act in itself—when you’ve really faced this fear, and given up your friends and job for it—gives you the strength to go on and pursue what you wanted to pursue.” New York was freedom, but the break was not clean. For a long time, his old thinking would reappear. He carried guilt about coming out, and then, later, embarrassment about his time with the organization.

But all of this was gone by the time he saw the images again. Recognizing their value as both the evidence of a growing artist and insider snapshots of a once-flourishing religion, he decided to publish them in a photobook. “People had responded to [the pictures],” he said. “The only way I could bring conclusion and closure was by taking an action.”

—Alex Zafiris for Guernica

Greg Reynolds is a photographer based in New York City and Kentucky. Jesus Days, 1978-1983 is out now on Bywater Bros. Editions.