By Jan Bindas-Tenney

Green Valley, Arizona, happens all of a sudden—like a speed bump—with long green golf courses in the brown desert, sandwiched between the Santa Rita and Sierrita mountains. The arid expanse stretches wide, full of prickly pear and saguaro cacti, ocotillos stretching their strange spiny arms. The green tailings of an open-pit copper mine leave tall fake mesas along the road. Then there’s Green Valley, a lush enclave lined with palm trees. A series of culs-de-sac—the retirement bungalows in neat arabesques and spherical trigonometries—dead-end where white-haired men in Speedos and women in flowered bathing caps fill an outdoor pool, bouncing beach balls lazily over a net. At the public library a line of golf carts crowds the front entrance. Under the shade of pavilion roofs 30,000 retirees in pastel cloth jackets bask in 330 days of sun per year.

In the preparation for sanctuary there will always be some erasing, some genocide, some bleaching of the alleys.

Green Valley is a leisureville tucked away from the ills of late capitalism where American retirees look to live out their golden years in the sun. Many argue that utopian seclusion is impossible: political theorist George Kateb asserts in his 1963 book Utopia and Its Enemies: “Give up the vision of utopianism, though it may be a worthy vision, because there is no way to go from the real world to utopia; or if there is a way, it could be none other than the way of violence.” He argues that in the process of seeking perfection, dead bodies will always turn up on the outskirts of town. In the preparation for sanctuary there will always be some erasing, some genocide, some bleaching of the alleys.

In this case, there are dead bodies in the pecan fields. Leisureville’s boundary abuts the last border checkpoint heading north from Sonora, Mexico. People walk through the desert to Green Valley heading north. Some show up dehydrated, some show up and die. Border patrol car-chases buzz the streets while helicopters hover at night.

The Green Valley Samaritans meet every two weeks at the Good Shepherd Church, a low-lying modern building with brown carpet and wooden chairs. Harry and Ed run the water drops; they drive deep into the desert to leave gallon jugs of water along migrant trails.

I realize that when these old folks look at the desert, they see Jesus. … They see tired pilgrims who need saving.

Everyone turns my way as I arrive at the meeting. Several women smile and nod. A grandma stands up holding a walking stick, a sandal, and a bloody cloth. She says that during one of her searches she found these items all in a line—like a message from God. She says this is miraculous. I realize that when these old folks look at the desert, they see Jesus. They see the sand dunes of the Middle East and the second coming. They see tired pilgrims who need saving.

Harry, Ed, and Jack usually head out early on Friday mornings when the sun is still rising pink over the Santa Rita Mountains. They agree to take me with them. Ed and Harry meet at the church, pick me up by the McDonald’s, and then pick up Jack farther south by the Long Horn Grill. The Grill is closed now, but it has a twenty-foot tall big-horn sheep skull for an entryway. Jack tells me that “it’s been in the movies, you know.” Ed is wiry and all smiles, deep wrinkles around his eyes and lightness in his step. Harry is a bit younger and stockier; he has buzz cut hair and strong shoulders—a former firefighter. Both Ed and Harry wear bright red baseball caps that say SAMARITAN in white lettering. Jack has white hair pulled back into a ponytail and a scraggly mustache yellowed from smoking. Jack hunches over, looking his age. Harry drives.

Jack creaks into the car and holds his head in his hands, “Don’t mind me, I’m in a bad mood. Just had a terrible run-in with Border Patrol.”

“Oh yeah?” Harry and Ed ask.

Jack continues, “They pulled me over on Arivaca Road and the kid asked me to get out of the truck. Nope. Give me the keys. Nope. Give me your license. Nope. I’m going to call the Sherriff. That’s when I knew he was really full of shit. He said he was just doing a routine search. I said search away! He asked for my keys. I said nope.”

“Did he call the Sherriff?” Asked Harry.

“No, he didn’t. I knew he wouldn’t. Eventually he let me go. He must have called ahead, because when I got to the Border Patrol checkpoint they just waved me through. My face is still hot.”

Harry and Ed stay quiet. Harry drives south toward Walker Canyon—National Forest property with active migrant trails. The guys have seventy-two gallons of water in the back of the car stacked in milk crates. They talk about television, that Jewish channel with the funny ethnic comedians, how broadcast is better than satellite dish: The Three Stooges, Mr. Ed, and I Love Lucy. Ed pretends to be one of the stooges and puts his hand vertical between his eyes. “It really does work!” He says. They joke with each other, poke fun, and laugh the whole way.

Harry tells a story about going to Walgreens in Green Valley with his wife late at night and seeing two young migrants sitting on a bench. One of them asked to use his phone. Harry let him, he talked for a while, and then the kid passed Harry back the phone. The voice on the other line asked Harry to tell him where he could meet his son; Harry gave the man directions and ended the call. The young men disappeared into the night. They are somebody’s sons, Harry said. They are somebody’s fathers.

Harry, Ed, and Jack make five stops in Walker Canyon each carrying two gallons of water in their packs as they ramble slowly along the gravel path. With steep rock walls, the canyon twists and rises with tall trees on either side, peeling sycamore, and the scaled plated bark of alligator juniper trees. At the first two drops the water from a couple of weeks ago is still there, untouched. Ed makes notations in an old spiral notebook: date, usage, new, remaining.

“These spots haven’t been very busy, but we come back anyway. Sometimes trails get active for a couple months then the traffic drops off. It takes us a long time to switch drops, though. We want to make sure if people need it, the water is there,” reports Ed.

I imagine what it must feel like to walk in the desert for days without water, to come upon a cluster of vandalized, empty gallon bottles.

At the third spot the guys find twelve gallons of water vandalized, empty plastic bottles with pen-sized holes poked in the bottom and all the water drained. I imagine what it must feel like to walk in the desert for days without water, to come upon a cluster of vandalized, empty gallon bottles.

“This is disgusting,” Harry says, picking up a couple empty gallons and throwing them back down.

Jack fumes. “Fuck these motherfuckers. Let them come find us here now. I’ll show ’em.” He raises his fist above his head and shakes it.

Ed offers to go back to the car to get more bottles. He walks most of the way back and realizes that he forgot the keys and has to run back again. Jack says he’ll stay there with a radio and wait for the Border Patrol to try to come and vandalize one more gallon of water.

“Leave me here. Let them try to do that with me here,” Jack makes boxing motions with his hands as he totters on a cluster of rocks. Jack’s back hunches; his skin is sallow and he breathes heavily.

Harry offers, “I don’t think it’s a good idea, Jack. We won’t be able to hear you on the radio because of the mountain.” He points up; Jack finally agrees. They walk slowly back to the car. Jack mutters under his breath; he has “always” been a troublemaker. The first time he got arrested he chained himself to a nuclear power plant in New Hampshire back in the ’60s. Jack moved to Green Valley a couple years ago when the northern Vermont winters got hard on his joints. He has three children, eight grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

As Harry starts the car and heads towards drop number four he says, “Yeah, last time we were here, remember we saw those Border Patrol guys who wouldn’t even talk to us. It’s always a bad sign when they won’t even talk to you. I bet it was them.”

“They are always a bad sign, period,” says Jack.

“They usually show up after drop number four,” explains Ed. He guesses that there must be some kind of motion sensor hidden in the bush. When we get to drop four, we each carry two gallons again on the short path through the woods. The sycamore trees are bright yellow and orange, a piece of Eastern fall fire in the dry desert. The jugs they dropped a month ago sit on a rocky incline half empty, some empty with tops off.

“We have some usage here,” says Harry. A couple of the bottles have teeth marks on the blue caps and may have been chewed by an animal. “Eight new bottles will be good.” On the way back to the car a young pink-cheeked Border Patrol agent on a four-wheeler wearing a green uniform revs up the path. He slows and kills the engine.

“How ya doing?” says Harry, raising an arm in greeting.

“Good. How about you?”

“Oh, great,” says Ed. “Wonderful weather we’re having here.” He points to the sky, which is overcast—an anomaly for Southern Arizona. Ed asks if it’s been busy.

“Real busy,” says the young man.

“Yeah, busy vandalizing our water,” says Jack as he walks by in a huff and sits on the back bumper of the car.

“We don’t touch your water,” says the Border Patrol agent. Everyone nods in agreement, says their pleasantries, and continues on.

“I can’t stand ’em,” says Jack.

Drop number five is uneventful. No usage, no vandalism. Everyone piles into the car to head home. On the way out we spot two Border Patrol agents on horseback heading in the way we came.

As we drive home from the water drops, Harry turns back and, almost whispering, he says:

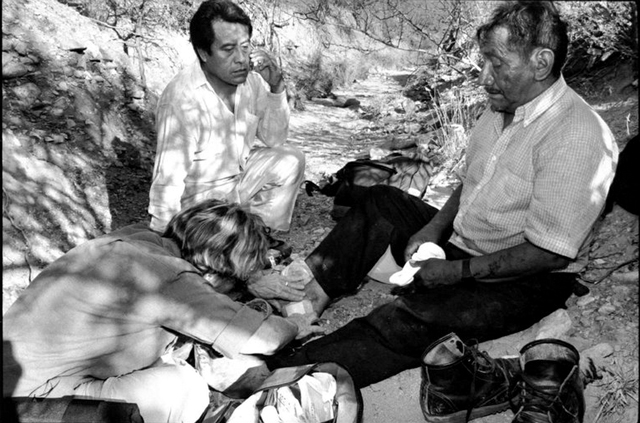

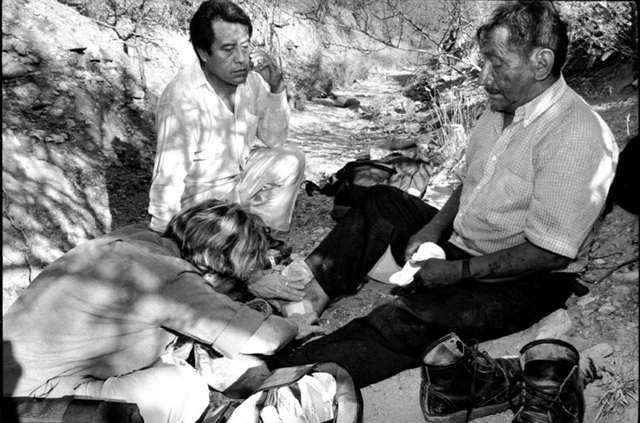

“Once, right here under that tree, my neighbor, who speaks some Spanish, found these two guys who had just walked in from the desert. They were in trouble, dehydrated, vomiting, with bad ankle sprains. I helped them out.”

Harry pauses.

“A couple months later my neighbor saw one of the guys working for a roofing company in town. He ran up to her—‘remember me? remember me?’ He asked about me and said he would fix both our roofs for free whenever we needed it. He gave her a free coating a couple days later.”

Harry smiles as he drives.

Harry says the black dust from the copper mine settles thick on everything in his house. He can’t stand it. As the guys pull into the realty office parking lot, a line of cars waits for McDonald’s coffee across the street. Two elderly women in bright yellow cloth jackets zoom by in a golf cart and beep their horn. A billboard for the Titan Missile Museum looms above the highway overpass: “Duck and cover!” The sun is high now that the morning clouds have burned off and the Santa Rita Mountains rise and fall like the silhouette of a giant face lying down in the desert. A man in a baseball cap stands on the median on Continental Road with a sign: “Marriage: One Woman, One Man.” Ed and Harry throw their hands up and sigh.

“So, we’ll meet the same time same place next Friday?” Ed asks. Harry nods.

Jan Bindas-Tenney is a candidate in the nonfiction MFA Creative Writing Program at the University of Arizona. For the past decade she was a labor and community organizer. Her writing examines social and environmental injustice, place and displacement, and what it takes to form community. Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in CutBank’s, All Accounts and Mixtures, Cactus Heart Literary Magazine, and Squalorly Journal, among other places.