By Jacqueline Feldman

On Saturday, trucks decked out as floats stretched from Montparnasse Tower toward where the Eiffel Tower pokes the sky. Years ago, this parade was called Gay Pride, then re-dubbed into French: La Marche des fiertés. Paris’s march, an American import, dates to 1971. It differs somewhat from its counterpart in the United States in that the French are less familiar than Americans with civic parades, and more prone to political marches.

Recently the French have marched for gay marriage and against it. France became the fourteenth country to legalize same-sex marriage in May. Proponents here call it mariage pour tous, marriage for everyone. The law also opened adoption to same-sex couples. Marriage is the American sticking point, but adoption has been more controversial than same-sex marriage in France. Marchers against the new law who called themselves the Manif pour tous (Protest for everyone) continued to demonstrate after its passage. In January, the group drew 340,000 marchers, according to police, or 800,000, according to its organizers. In late May, it still drew 150,000, according to police, or one million, according to Manif. Uniting conservative and religious groups, mostly Catholic ones, the anti-marriage cause has also helped far-right nationalist groups to form and fester amid recession and Hollande’s unpopularity. Sometimes Manif activists were violent during marches, rushing police barriers May 26, throwing smoke bombs, metal bars, and beer bottles, singing “La Marseillaise.”

The attackers said, “Hey, look, gays,” then pounded de Bruijn’s face into a red mess.

Before the Pride march, Ronan Rosec, secretary for national organization SOS Homophobie, manned a pink-blanketed table beside the floats. “Homophobes who had stayed very discreet these recent years, since the vote on the law to legalize civil unions, showed their faces,” he said. Behind him, the sun came out over the parade. “Fraternité has been seriously forgotten in these recent months.” On the table lay copies of the organization’s latest report, which shows a threefold increase in homophobic acts reported to its hotline in the first months of 2013. These included instances of discrimination and hate speech as well as violent acts.

Shortly before the law’s passage, Wilfred de Bruijn, a Dutch man who lives in Paris, was attacked while walking with his partner. The attackers said, “Hey, look, gays,” then pounded de Bruijn’s face into a red mess—a photograph of which spread virally over social media. “This is the face of homophobia,” de Bruijn wrote on Facebook. Legislative supporters of the law received death threats. Before the law was officially published, a gay bar in Lille was attacked. Men with shaved heads wounded three who worked there. One said he took a chair to the head. Another man was wounded during a simultaneous attack at a gay bar in Bordeaux. Vandals filmed themselves defacing a community center that was hosting LGBT-association events in central Paris. Wearing white masks that resembled those of current German neo-Nazis, they plastered the center in posters reading, “Don’t touch marriage.” They belonged to a far-right offshoot of Manif pour tous that calls itself Printemps Français, after the Arab Spring.

A 78-year-old man shot himself in Notre-Dame before fifteen hundred tourists and faithful after having lamented the marriage law on his Islamophobic blog that day. Marine Le Pen, who leads France’s National Front Party, tweeted her respect for a “final gesture” that “tried to wake up the people of France.” Thousands of rightist mourners gathered at the cathedral. Two weeks later, Clément Méric, a 19-year-old student and leftist activist, was killed in a fight with skinheads linked to a group called Revolutionary Nationalist Youth. A few days before Pride, a crowd of six thousand assembled at the Garnier Opera to march in Méric’s memory. Méric’s high-boned, heart-shaped face stared from anti-fascist posters across the city. He looked nearer 12 than 19.

Hours before the Pride march Saturday, the marchers were testing speakers, climbing stepladders, exhaling into balloons, and eating sandwiches. A clutch of orange, helium-filled balloons slipped off a truck and quickly rose above Montparnasse Tower. La République a dit oui!, “The Republic said yes!” read the float for Hollande’s Socialist Party. “It’s more than a victory, because this is a historic moment,” said Frédéric Felix, president of Gai Moto Club, an association of motorcyclists that traditionally leads the parade in Paris.

Behind white face paint, expertly lined lips and eyes, false eyelashes, and complexly patterned tights, they sang hymns.

For other marchers, the day was less than purely celebratory. Activists who believe Hollande has failed them picketed politicians who were readying to march. They chanted that the Socialists were “hypocrites” and “traitors,” referring to medically assisted procreation, which is not open to same-sex couples in France. Fatima-Ezzahra Benomar, founder of a feminist and LGBT group called Les efFRONTé-e-s, was one of the protesters. “For us, equality is not only marriage and adoption,” she said. “The left has not kept its promises.”

A speaker from Inter-LGBT, the organization that runs Pride, invoked the recent, victorious law but also the work that remains to fight discrimination and extend reproductive rights in France. The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an order of drag queens, offered their traditional blessing of Pride. Behind white face paint, expertly lined lips and eyes, false eyelashes, and complexly patterned tights, they sang hymns. “Be proud, my sisters,” said one. “Be proud, my friends… above all, be militant… I wish you all a very, very good march.” Another played a recording of church bells, amplifying it with a megaphone. When these Sisters consecrated the Pride march in Toulouse, they dedicated it to Méric.

As the parade set off, marchers were still improving their kits with silver spray paint. Drag queens—continuously photographed by onlookers—wore platform boots or chiffon wings. Two young women, Joanna Abadie, who is 28, and Karime Desplace, who is 32, wore matching t-shirts that read, “She said yes” and “I said yes.” Abadie had proposed to Desplace the previous day at a park with a view of the city, after they went out for Chinese food. Asked whether this march bore special importance for her, Abadie said, widely smiling, “Not any more for us than for anyone else.”

Spectators shared orange juice and beer and candy. A man sold rainbow flags and heart-shaped plastic sunglasses out of a shopping cart. A woman sold leis for two euros apiece. Marchers on a float for LGBT policemen sprayed the sidewalk-bound with Super Soakers, blowing whistles. Confetti erupted from the floats. One truck carried white cardboard cutouts of hanged men cut, much larger than life, wearing nooses and the flags of countries where homosexuality is punishable by death.

A man dressed as the Queen of England in a powder-blue gown and crown walked surrounded by men in kilts and black peaked helmets, waving Union Jacks. He dragged on an electronic cigarette—trendy in Paris—as his entourage passed Notre-Dame-des-Champs, a nineteenth-century church with a series of paintings about the Virgin Mary. Paris is separated from, say, San Francisco, by the visibility of its history. The present is not easily unloaded of its past. An inflated condom about three stories tall was competing with Montparnasse Tower. Teenagers climbed atop bus-stop shelters, making them shake. The parade molted fliers, cigarette cartons, and lollipop sticks, and these covered the road.

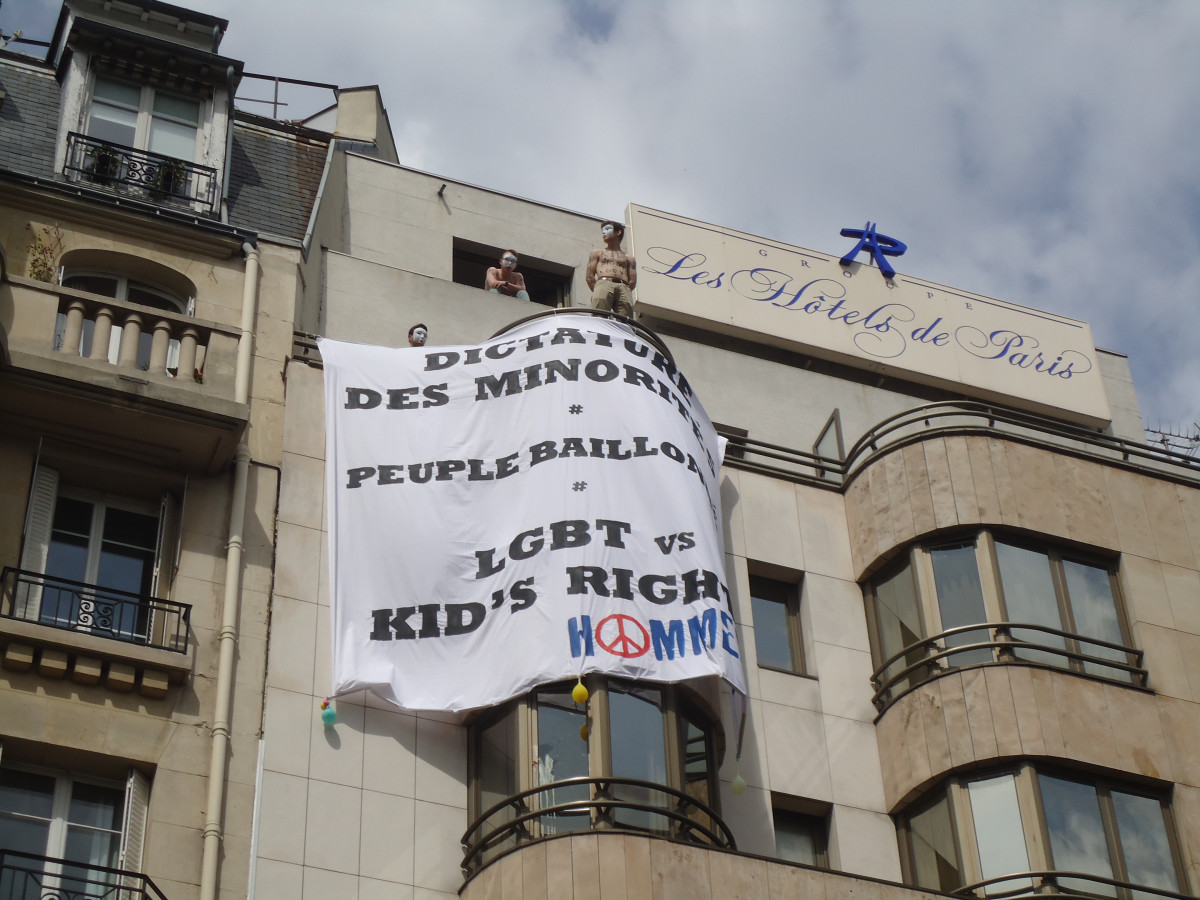

At Vavin the marchers met with a white banner two stories long and just as wide over a hotel façade. On a top-floor balcony stood five men who wore the same white masks as the recent vandals. They belonged to a new group called Hommen, which adheres to the Printemps Français, purporting to speak for a “silent majority” of French. The group believes it protects a kind of French family that is imperiled when gay couples adopt children. The banner read, “Dictatorship of Minorities / A People Silenced / LGBT vs. KID’S RIGHTS HOMMEN.” Hommen had recently interrupted the French Open in protest and otherwise punted for glory. Now the men stood absolutely still, their arms stretched skyward, their hands clenched into fists.

“There is an increase of fascism everywhere in Europe…Homophobia has found a flag.”

Some marchers turned their heads and stopped. Many gave the men the finger. Some shouted for them to come down. Hervé Marsal and Claude Beecher, a gay couple who will wed this August, rushed into the hotel with a few others, but the masked men would not answer to knocks at their door. Marsal and Beecher said they wanted the men to remove the banner, or at least their masks. “Obviously they are too cowardly,” Beecher said. “There is an increase of fascism everywhere in Europe… Homophobia has found a flag.”

A dozen armored policemen gathered before the hotel, protecting the men on the balcony. Marchers waving the red flags of the French Communist Party now were chanting: “Facho, bastard, the people will have your hide.” Others started a call-and-response chant that had reverberated during rallies for Méric: “No fascists in our quarter, no quarter for fascists.” The men on the balcony stood motionless.

Pride marchers under anti-fascist banners and anarchist ones now stopped en masse, halting the parade. A young woman with pink sequined fabric wrapped around her head led chants through a megaphone: “Stay there, don’t come down”; “Antifascists, rise up, rise up”; “Paris, Paris, anti-fa.” The policemen donned helmets, facing down Pride. The marchers punched the air and chanted, “Police, go please, homophobes, assassins.”

Eventually the marchers continued. They walked and danced past the Luxembourg Gardens and the Arab World Institute, threading Sully bridge to reach Bastille. They blew bubbles. D.J.’s spun. Gaga blasted. Men along the way sold sausages from carts and Heineken from baskets strapped to their shoulders. At Bastille, a stage was illuminated, and those who’d walked far crowded the steps of the sleek, modern opera house, resting, having cigarettes or ice cream. A concert started there and went on into the night.

The men of Hommen stayed on the balcony. After the last float—a car decorated as a pirate ship—police vans slowly followed, then came city cleaners. Confetti, fliers, and trash circled in aerial eddies over the sidewalk before the hotel. All but five policemen wandered off. But Hommen stayed. Men in uniforms swept the street with brooms and leaf-blowers. Green vehicles blasted the boulevard with water, leaving a misty film. The remaining police left.

The white-masked men stood motionless on the balcony. They watched the street re-fill with normal traffic. Families passed below them. Hommen looked down on women with strollers, girls in sundresses, a straight couple on bicycles, a man in a wheelchair, a pregnant woman in a pretty scarf, an elderly straight couple in matching denim jackets, and a guy with tennis equipment. From such a height, these people must have appeared small and powerless to the shirtless men. Walking toward Montparnasse train station, they must have seemed to be running away. Hommen stood still above the hateful banner.

Now it was not clear what the men stood for. The parade’s many speakers were now inaudible. There was little confetti anymore. There was no one to stand against. But the men had secured a position of great and fearful height from which to look down on all Paris. Thusly established, they did not move.

Jacqueline Feldman is a writer and Fulbright fellow in Paris. Read more of her work on her website.