Panorama of Fenway Park in 1912

The first, and last, time a professional sports team made me cry was 1978, when the Boston Red Sox lost a one-game playoff to the New York Yankees to determine who would go to the postseason. I was ten. Perhaps it is telling that I’ve never thought of the Yankees as having been responsible. The Red Sox made me cry, by losing. The game had started in the afternoon and I’d raced a mile home from school to catch it in the early innings, watching on a twelve-inch, black-and-white set. The Red Sox took an early lead, but then in the seventh inning, with two runners on base, Bucky Dent, the Yankees’ anemic shortstop, mishit a pitch and popped it a mile high. The wind was howling across the Boston Fens that day, as it used to do. It took hold of the ball and, impossibly, carried it right over the thirty-seven-foot-high Green Monster, opening up a pit in my stomach that wouldn’t really close for twenty-six years.

The final score was five-four. A friend of my parents who was visiting from New York saw me unable to stanch the flow and smiled and said he cried the same way when the Brooklyn Dodgers lost their final playoff game five-four in 1951. Same thing, he said. But it wasn’t. The Dodgers lost fair and square on “The Shot Heard ’round the World,” a screaming line drive by Bobby Thompson. The Red Sox lost on a friggin’ popup.

Today, people think “The Wall,” as it came to be known, was built to compensate for the shortness of left field—to make it a little tougher for batters to hit a home run. But in 1912, the Dead-Ball Era, few batters could hit the ball that far. Frank “Home Run” Baker would lead the American League in home runs in 1912 with ten. He led the league every year from 1911 to 1914, never hitting more than twelve in a season. The Wall was supposed to change behavior outside the park, not inside.

Yet from the start, it had a strange impact on the game. A ten-foot embankment was built on the field side of the wooden wall to support it. It started at about the three hundred-foot mark on the field, rising upward at a steep angle to meet the wall. This became a natural gallery for overflow crowds, who in those days would be packed onto the embankment, becoming a living part of the game.

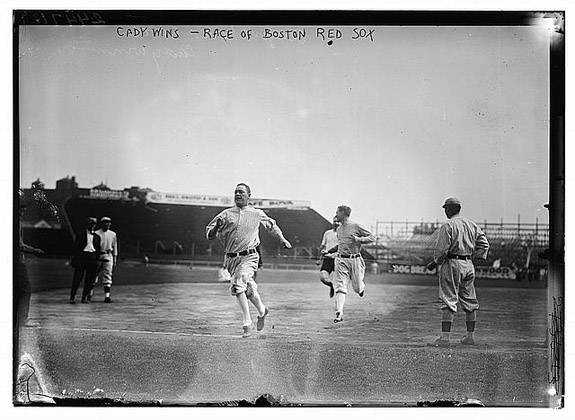

Try running backward while tracking a flying baseball over your head. It’s a lot harder than it looks. Now try doing it and—no peeking!—let the field be littered with bodies as it rises sharply beneath you. It quickly became sport at Fenway to watch left fielders wipe out in front of The Wall. The Red Sox own left fielder of the time, Duffy Lewis, became so good at scaling the embankment that it came to be known as “Duffy’s Cliff,” the first of many Fenway features to take on a proper name. “They made a mountain goat out of me,” Lewis later recalled. Lewis’s heroics, in the field and at the plate, helped the Red Sox win the 1912 World Series, four games to three, over the New York Giants, completing Fenway’s wildly successful first year.

The Sox went on to win three of the next six World Series. They were the kings of the American League, and Fenway Park was their palace. They had a budding young star named Babe Ruth. No one could have predicted that, after trading Ruth to the Yankees in 1919, they would not win another World Series for eighty-five years, and that, like some haunted battlefield, Fenway Park would gradually take on entirely different associations.

Duffy’s Cliff was leveled as part of a major renovation in 1934. It had become an embarrassment for the Red Sox, who in 1932 had acquired a famously inept fielder named Smead Jolley. Concerned about Jolley’s ability to navigate Duffy’s Cliff, the Red Sox coaches spent days training him how to climb it. When Jolley’s chance came in a game, he flawlessly ascended the slope, retrieved the ball, turned to throw, slipped, and tumbled. Asked about it after the game, Jolley snarled, “They taught me to climb up the damn hill, but not how to come down.” Not learning their lesson (and continuing a long tradition of favoring overweight sluggers over athletes), the Red Sox replaced Jolly in 1933 with Bob “Fatty” Fothergill, who was shaped like a jelly doughnut. Legend has it that, not long after his arrival, Fatty Fothergill scrambled up Duffy’s Cliff after a fly ball, tripped, rolled all the way down, and retired from baseball shortly thereafter.

The Wall was raised to its current thirty-seven-foot height as part of that 1934 renovation. By then, livelier baseballs were flying out of parks at unimagined rates—Babe Ruth had smacked sixty homers in 1927—and left field in Fenway had become a joke. So The Wall was raised to thirty-seven feet, new concrete footings were installed, and a hand-operated scoreboard was added at the base of The Wall. The scoreboard (now in its second edition; the rusty original sits in a warehouse in South Dakota) is still manned by three young men standing in the narrow vestibule inside the wall, watching the game through horizontal arrow slits. They use red and green lights to track balls, strikes, and outs, but they update the scores of all American League games by hanging twelve-by-sixteen-inch metal plates on the inside of the wall that show through square windows in the wall; national league scores must be updated by hanging plates on the outside of the wall. Between innings, a door mysteriously opens, and a Wall elf emerges carrying a stepladder and whatever plates he needs.

The 1934 renovation also added new right-field bleachers, which were merged with the center-field bleachers at an oblique angle that must have driven the carpenters nuts. No effort was made to blend together the various walls. The right-field stands simply stopped when they ran smack into the center-field ones in a bizarre triangle 420 feet from home plate, having first taken a detour midway along their length so they wouldn’t block a garage door in the center-field wall. The resulting walls go from thirty-seven feet high in left field to sixteen feet high in center field, then a mere four feet high in right, all of them meeting at random angles. The impression is of a park constructed from whatever pieces were lying around the yard. The fence makes six abrupt turns from left field to right, where it suddenly goes into a swooping curve. This is not unlike the route I’ve followed every time I’ve made the questionable decision to drive through Boston, a city whose cow paths ossified into streets more than three centuries ago. Perhaps every city gets the ballpark it deserves.

In his next line, however, Updike turns around and nails the place in twenty words. “Everything is painted green and seems in curiously sharp focus, like the inside of an old-fashioned peeping-type Easter egg.”

It’s easy to forget how weird it is that Major League Baseball fields are irregular. Imagine if a National Football League team announced that they were going with an oblong field, or an NBA team decided to raise its basket to eleven feet. No way. Uniformity and fairness are sacrosanct. Yet in baseball, the field dimensions vary wildly from park to park and have a strong influence on the game. Somehow baseball’s whimsical past has been grandfathered into the businesslike present, to the point that quirks and asymmetry are almost standard in the design of the new “retro” ballparks. A waterfall here, a passing train there. Yet most of these quirks feel as arbitrary as the cul-de-sacs and street names in a new subdivision. Only Fenway came by its features and place names—the Green Monster, the Triangle, Williamsburg, Pesky’s Pole—through evolution. And, like all evolution, there was no master plan, just ongoing adaptations to new situations, a century of ad-hoc solutions that, from a distance, might be mistaken for design. Form follows function. And suddenly you have a platypus on your hands.

The Wall didn’t become the Green Monster until 1947, when millionaire owner Thomas Yawkey decided to paint the entire edifice green, perhaps as a way to give the park some sense of unity. Those who decry the handful of green-and-white ads that adorn The Wall today should have seen it before Yawkey’s paint job, when every square inch was festooned with ads for cigarettes and gasoline and BVD underwear. Today the park is painted a proprietary shade known as “Fenway Green,” which has a weird blue-gray tint and is the uninspired color of something you’d pick up at an Army Navy surplus store. One’s overall impression, upon walking up the ramp into the stands and seeing the field for the first time, is not of grandeur or gravitas, but rather of something built by an awkward child.

“Fenway Park, in Boston, is a lyric little bandbox of a ballpark,” John Updike began his famous 1960 New Yorker piece about Ted Williams’ last game. It’s the most-quoted line ever written about the park. Pure poetry. And pure fantasy. There’s nothing harmonic about the place. It’s as lyric as a pinball machine.

In his next line, however, Updike turns around and nails the place in twenty words. “Everything is painted green and seems in curiously sharp focus, like the inside of an old-fashioned peeping-type Easter egg.” Indeed, it all seems right in your face, the field and the stands and especially the Green Monster, as if you were wearing 3-D glasses and expected your hand to touch the Wall when you groped out in front of you. Tip O’Neill got it right when he compared Fenway to “an English Theater. You’re right on top of the stage.” And the fans are just as fickle, ready to turn on a single flub. This is especially true in the left-field corner, where the Green Monster meets the high stands that encroach within inches of the foul line, allowing fans to lean out over the left fielder and use him as a sort of sporting human sacrifice. Ted Williams used to spit back at them. Carl Yastrzemski once wore cotton balls in his ears. “The big thing about Fenway is the crowd,” says pitcher Dennis Eckersley, who knew good times and bad there. “It’s like in the days of the Romans in the Colosseum … they’re right on you. There’s no other park like that.”

The left-field stands approach the foul line at a forty-five-degree angle until they are within inches of it, then turn and parallel it all the way to the Green Monster. The strange angle provides for some truly weird plays, because any ball hit past third base (and thus fair) with a little angle or curve to it will ricochet off the Budweiser ad in front of the slanting stands and take a right turn, ending up somewhere behind second base. Left fielders new to Fenway are usually headed full speed into the left-field corner when this happens, and have to be rescued by the shortstop. At Fenway, fair is foul, and foul is fair, as veteran left fielders eventually learn. But on September 1, 2011, Yankees left fielder Brett Gardner, one of the best, experienced the opposite. A ball hit by longtime Red Sox catcher Jason Varitek skipped off the third-base bag (fair!), hit the front corner of the stands, and took a bounce that seemingly defied the laws of physics, doing a tightrope walk along the top of the wall, then slipping down to the base of the wall and hugging the edge of the stands all the way out to the far left corner of the Green Monster. An extra run scored and Varitek wound up with a gift double. “We’ve played here a lot and you know the angles of the field, the different dimensions and how balls kick off places,” Gardner said. “That probably never happened before as long as this park’s been here.”

Yet bad bounces are a defining feature of life at Fenway. I present Exhibit A: The Ladder, which sits bolted to the Green Monster, running from a point above the scoreboard to the top of the wall, and projecting a few inches out from it. The team is fond of pointing out, though really it goes without saying, that this is the only ladder in play in Major League Baseball. The ladder has been responsible for much weirdness, including at least two inside-the-park home runs, one of which in 1963 caromed from the ladder to outfielder Vic Davalillo’s head before rolling away. At least then it had a purpose; after each game, the grounds crew would climb the ladder to retrieve balls hit into the screen atop the Green Monster. (The screen was there to protect windows on Lansdowne Street.) But since the Monster Seats replaced the net in 2003, the ladder has been an atavism. It exists solely to screw things up. In a June 2010 game, Red Sox rookie Daniel Nava suffered a virtual fielding meltdown at the hands of The Wall, including a shot that rattled around the ladder and allowed an extra run to score. “I was like, ‘No way this ball is going to go off the ladder.’” Nava sighed after the game. “‘Oh, it went off the ladder.’ ‘Oh, it hit the ladder and got stuck in the ladder.’ It happens. I can’t control that.”

The usual justification for such irregularities is that it takes us back to the carefree sandlot games of our youth. If you hit the ball just right and it got into the alley between the Hendersons’ house and the Greeleys’, well, you could run all day. I grew up playing in a literal sand pit, with fifteen-foot walls chewed out of a hillside by excavators forming a natural amphitheater and home run fence. Clawing up those sandy slopes after fly balls was my own version of Duffy’s Cliff.

But professional ball players aren’t really expected to play the game like kids. Not when hundreds of millions of dollars are at stake. From 2001 to 2008 the Red Sox had a left fielder who played the game exactly like the preternaturally gifted, and distracted, thirteen-year-old he had been growing up in New York City, and it was problematic. Manny Ramirez—a hulking, dreadlocked Dominican-American—was the greatest natural hitter of his era and a total space cadet. He took fielding about as seriously as flossing. Manny used to disappear into The Wall between innings, through the scoreboard operators’ door, sometimes delaying the start of the next inning. What was he doing in there? Getting a drink? Peeing? Once he slipped into The Wall during a sixth-inning pitching change, a window opened, and he could be seen chatting on a cell phone. The general consensus was that he wasn’t treating the game with the proper respect. This, despite the fact that Manny was ordering his pizza, or whatever he was doing, just a few feet below the most ridiculous ladder in America. Boston as a city is borderline OCD about its rituals and traditions. But the ladder begs the question: When does tradition become debilitating?

The Red Sox managed to make it to the World Series in 1946, 1967, 1975, and 1986, losing every one of those series—every one—in seven games. I wasn’t around in ’46 or ’67, was too young to be scarred by ’75, but I have every play from 1986 burned into my hippocampus. That series had actually looked pretty good for the Red Sox for a while. They won Game Five at Fenway Park to take a three-two game lead over the Mets, then in Game Six, they took a five-three lead in the top of the tenth inning. The first two Mets went quietly in the bottom of the tenth. The Red Sox became the only team to ever come within one strike of winning a World Series and then lose it. (The Texas Rangers equaled this feat last October.) Gary Carter singled. Kevin Mitchell singled. Ray Knight singled. Five-four. Bob Stanley threw a wild pitch to Mookie Wilson, scoring Mitchell and sending Knight to second. Five-five. Wilson dribbled a slow roller to first, but the ball took a weird hop and Bill Buckner, a good defensive player almost crippled by injuries, let it roll between his legs. Game over. The Red Sox blew another lead the next night and lost Game Seven, too. I didn’t cry. I was in college. You can’t cry over a baseball game when you’re in college.

Why not ritualize the trauma? Entomb it, like a Wellfleet oyster shellacking a painful sand grain in nacre, and turn it into a pearl?

But Wade Boggs, the Red Sox third baseman, sat alone in the dugout after the game and blubbered. Boggs, who more than any other Red Sox player made The Wall his lodestar, tailoring his swing to flare doubles off of it. Boggs, the most scientific of hitters, nonetheless staggered by superstitions. Boggs, who ate chicken before every game, after having once gone five for five in a minor league game after a chicken dinner. Who took exactly 150 ground balls in fielding practice every day, took batting practice at 5:17 p.m. every evening, ran his wind sprints at 7:17 p.m., and followed the same indirect route from the dugout to his fielding position every time. Who traced the Hebrew word for life, chai, into the dirt of the batter’s box before every at bat.

A few years later, when it was announced that the tunnel being constructed in Boston to link I-93 and Logan Airport would be named the Ted Williams Tunnel, some wise guy proposed naming it the Buckner Tunnel instead, with the cars rolling through a giant arch in the shape of the first basemen’s legs, an oversized glove hanging at the top of the arch, a little too high. I was all for it. Why not ritualize the trauma? Entomb it, like a Wellfleet oyster shellacking a painful sand grain in nacre, and turn it into a pearl? This is what human beings have always done to cope with the malign forces they believed were conspiring against them. At times it has felt like the only coping mechanism at Fenway, which has been running the same drama in its little English theater for a hundred years: A story about chance. At Fenway, pop flies become home runs. 418-foot drives into the Triangle, easy home runs in other parks, settle into the glove of the center fielder like the white moth settling into the fat, dimpled spider’s grasp, in that archetypal New England poet’s take on the same issue. Who’s in charge here? When asked about their epic 2011 collapse, Red Sox first baseman Adrian Gonzalez replied, “I’m a firm believer that God has a plan, and it wasn’t in his plan for us to move forward.” Bummer.

“When confronted with numbers like these, you have to start to ask a few questions, statistical and existential,” Silver will write. “One should also have the license in situations like these to turn to various divine and karmic explanations.”

They were as dead as dead could be. Down three games to none to the Yankees in the best-of-seven American League Championship Series. They came from behind to win Game Four in extra innings, then won Game Five in extra innings, too. But they wouldn’t have won in any park other than Fenway. That’s because with the score tied in the top of the ninth, the Yankees had a runner on first with two outs. The Yankee batter laced a ball down the right-field line that hit fair and then bounced about four feet and two inches into the air, just clearing the tiny right-field wall and skipping into the stands for a ground-rule double, which means the runner on first was awarded third base. In any park with a normal wall, that ball stays in play, the runner scores, the Yankees win, and the Red Sox don’t go on to win that game in fourteen innings, the next two games, and the World Series in four straight over the St. Louis Cardinals. In case anyone doubted the surreal nature of everything that followed, the moon saw fit to go into a full lunar eclipse during the final hours of the series, and a blood-red orb hung in the heavens as the Red Sox exorcised their demons at last. Sox pitcher Curt Schilling wrote on his blog, “God has his fingerprints all over this game.”

I step onto the field at Fenway for the first time and walk out toward the Green Monster. In center field, the garage door is up to reveal people packed into the Bleacher Bar, a new watering hole chiseled beneath the center-field bleachers in yet another push to monetize every square inch of the platypus. Atop the Green Monster, a bridal party is milling about the Monster Seats. As I approach the wall, a roar goes up in the Bleacher Bar. Have the Red Sox scored? No, it turns out, the crowd is watching the Patriots. Recognizing the scent of disaster, the city has already begun to emotionally distance itself from the Sox, to go back into the defensive crouch.

In fact, the Sox will lose again today, and in a few days will complete the most improbable collapse in baseball history, snatching defeat from the jaws of victory on the season’s final play. On his New York Times blog, the statistician Nate Silver will calculate the chances of all the unlikely things happening that were necessary to prevent the Sox from making the playoffs at one in 278 million. “When confronted with numbers like these, you have to start to ask a few questions, statistical and existential,” Silver will write. “One should also have the license in situations like these to turn to various divine and karmic explanations.”

The Monster rises up before me. I’m surprised to see that it’s covered in ball marks. Scuffs and microdents, a palimpsest of moments past, of stirring hearts and lumpy throats. In my mind, I see Fisk’s home run clanging off the foul pole in ’75 to win Game Six of the World Series. I see Bucky Dent’s popup, see Yaz’s knees buckling in despair as the ball floats over the wall. And I see the Orioles’ Mark Reynolds smash a Josh Beckett curve ball into the Monster Seats four days ago, in the final game of the year at Fenway, to hasten the Sox’s demise.

Everywhere are the ghosts of left fielders past. To my left—I’ve heard of it but never before seen it—is the garage door where Yaz used to hide so he could sneak a cigarette between innings. Over there is the patch of grass where Manny Ramirez fell while chasing a ball, got up, then fell again, landing on the ball, which had to be extricated from beneath his rump by the centerfielder. It’s the same patch now patrolled by Carl Crawford, whom the Red Sox signed for $142 million before the season, and whose Fatty Fothergill-like flop on the final play of the final game sealed the Red Sox’s doom.

I step onto the warning track and try to picture Duffy’s Cliff, fans in top hats jeering the visiting left fielder. Then I reach out and touch the Green Monster. It’s hard as fate. No give. Sheet metal and rigid plastic. Strips of tin hold the sections together, some of them twisted and jagged. I wouldn’t want to run into it. The green and red lights that keep track of balls, strikes, and outs are domed, like old Cadillac taillights, just waiting to kick a ball sideways. Inexplicably, one of them is flat—a replacement for a smashed light, perhaps? The scoreboard, with its 127 recessed windows, is a minefield of rivets and sharp corners. I lean my back against it and stare straight up. The Monster soars above me, like some pockmarked god of randomness, eager to reinsert itself into the affairs of the nine on the field. Soon it will once again leer in the face of some redheaded kid who sits sniffling in the stands on a cold, blustery October night, questioning how some pop-fly homer could have possibly happened, staring around at this quizzical little bandbox and wondering who came up with such a design to appall. If design govern in a thing so small.