On the evening of September 22, 2015, James Zbeghn was unwinding in his home in the city of Ganta, a commercial hub about five hours north of Monrovia that lies at a crossroads between Guinea, Cote D’Ivoire, and the remote, dense forests of southeastern Liberia. As night fell, Zbeghn noticed that his son Cephus still hadn’t returned home. Cephus was a seventeen-year-old who earned small amounts of cash for the family by renting a motorcycle and ferrying people around Ganta. He rented the motorcycle he drove from a neighborhood entrepreneur, but generally he was home by then to return it.

Around the same time, another boy from the neighborhood, Jacob Vambo, dropped by Zbeghn’s modest family home in the quiet suburb. Zbeghn overheard Jacob’s conversation with another one of his sons, who was sitting near the house with a group of friends.

“Where’s Cephus?” asked Jacob.

Zbeghn was struck by his son’s confused reply: “You carried my brother today, you now come to ask me about him?”

Jacob seemed skittish, Zbeghn says, and intimidated by his son’s questions and the presence of his friends. He quickly left—without explaining where he’d last seen Cephus, which raised the suspicions of Zbeghn and the rest of his family.

After Jacob left, the evening passed into night, and Cephus still didn’t come home. Zbeghn visited the police station the following morning to report his son’s disappearance. He was surprised to see that Jacob was already there, dealing with a separate matter, related to the theft of a package of palm oil. Zbeghn pulled an officer aside and explained what had happened the previous night, accusing Jacob of knowing what happened to Cephus and where he was. When questioned, Jacob feigned ignorance, but when Zbeghn, an officer, and the owner of Cephus’s rented motorcycle searched Jacob’s yard, they found the bike under a tarp.” It was missing the colorful distinguishing fiberglass coverings that protect the engine, which would have made the bike easier to recognize, but the owner could tell it was his.

At daybreak, Cephus was still missing, prompting Zbeghn to alert the local police. Jacob was arrested shortly thereafter. For three days, police investigators interrogated Jacob. Finally, he broke, offering a startling confession. Cephus was dead, his body left in Jacob’s family’s sugar cane farm about thirty minutes outside Ganta.

Sergeant Adolphus Zuah, commander of the police detachment in Ganta at the time, was one of the officers on the scene. He theorizes that Cephus and Jacob had set out to steal a goat from a nearby town, but that Jacob decided to kill Cephus and take his motorcycle instead.

But rumors that traveled around Ganta in the days following the discovery of Cephus’s body hinted at something much uglier than a run-of-the-mill robbery. Whispers of a gruesome crime scene, with body parts extracted from the teenage boy’s corpse, were making the rounds in Ganta.

In an interview, Zuah dismissed the claims, saying that the body was too decomposed to tell if any parts were missing, despite only three days having passed between when Cephus was murdered and when Jacob led police to his corpse.

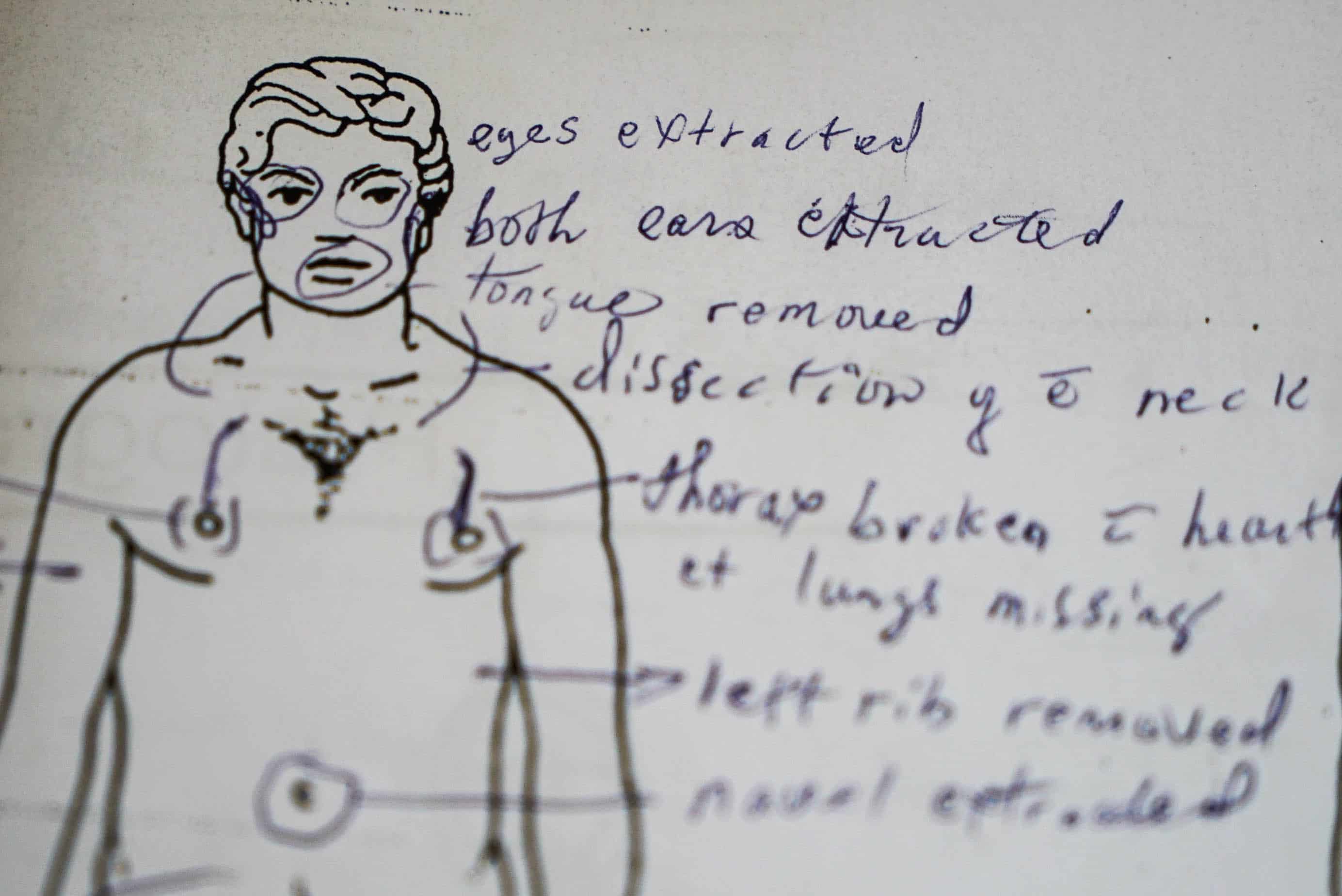

However, court transcripts from Jacob’s eventual trial tell a much more troubling story than the one offered by Zuah. And so does Jerry Tuah, the medical officer who examined Cephus’s body. When told of Zuah’s claim, Tuah shakes his head: “It isn’t true. Major organs were missing, along with his eyes, tongue, and ears. It was so terrible to see a young man killed in that manner.” Cephus’s arm and leg were broken, indicating that there was a struggle before he died.

Murders that fit such a disturbing pattern are common enough in Liberia to have a name: “ritual killings.” But when asked if they take place in Ganta, Zuah shakes his head: “I haven’t seen it.”

Photos of the crime scene in the case file offer a horrifying counter-argument. There are long gashes in Cephus’s torso, and a gaping hole above his breastbone reveals an open chest cavity. Patches of skin are missing from the skull. It’s difficult to imagine a seventeen-year-old committing such a brutal murder—and Jacob claims he did not.

Jacob admits he lured Cephus into the sugar cane patch, but he says he didn’t kill him. In his version of events, the murder was carried out by a powerful, high-ranking local government official, who offered to help pay for Jacob to attend university—in exchange for a favor. “I need some parts from a human and I would like you to find someone for me,” Jacob says he was told by the real killer, who, if the story is true, has converted the currency of his elite status into a brazen escape from justice, and is still walking the streets of Ganta as a free man.

***

The term “ritual killings” often evokes a mix of revulsion and sensationalist fascination among non-Liberians, and can play into ugly stereotypes about Africa: “witch doctors,” superstitious villagers in dark jungles, and fantasies about “juju”—West African magic. But for Liberians, they’re a real—and in some areas pressing—social problem. In late 2015, the United Nations released a human rights report about Liberia that devoted an entire chapter to the issue. In response, Ellen-Johnson Sirleaf, Liberia’s outgoing president, admitted that ritual killings were on the rise and vowed to “bring this ugly situation under immediate control.”

Local headlines in Liberia occasionally describe mysterious murders, where a body turns up missing vital organs and other parts. It can be hard to distinguish fact from fiction in many of these cases, which often turn out to be routine deaths or robberies. But other cases aren’t so easily dismissed, and nearly never include the arrest of a suspect. For many Liberians, the deaths point to the state’s inability to protect its citizens—or hold the powerful accountable for crimes they commit.

Long before Liberian authorities managed to assert their rule over the far-flung hinterland in the early 1900s, occult groups in the remote southeast used human blood to “feed” objects that were said to be a source of their powers, allowing them to turn themselves into leopards at will. In the post-war era, corpses have turned up missing their eyes, tongue, and other vital organs, particularly during election season. Liberians associate these killings with political elites, who are said to use the parts in rituals that they think will give them a spiritual edge in winning an election or receiving a promotion.

Ritual killings aren’t unique to Liberia. There’s evidence that they’ve taken place across West Africa, and are connected to the practice of what’s often called “witchcraft” or “juju.” Emmanuel Bowier, an expert on Liberian history who served as the country’s Minister of Information in the late 1980s, points out that similar killings have taken place throughout human history.

“Over the centuries in all civilizations, there’s this association between blood and power. This kind of thing has happened all over the world; it’s not a Liberian or African thing,” he said in an interview.

And belief in the presence of unseen forces that can be harnessed for personal gain is far from exclusive to Africa. Churchgoers in America are told that they can be healed through the “power of prayer,” and sports fans may believe that wearing a special jersey or waving a yellow towel might help their team win a game. The notion of ritual killing has even appeared in Western literature, as in Alan Moore’s graphic novel From Hell, which portrays Jack the Ripper as a high-level mason in Victorian England who carried out the famous murders partly to achieve a higher spiritual consciousness.

Witchcraft itself plays a complicated role in many African societies. The occult has become associated with satanic worship in Western consciousness, but in Liberia witchcraft is a neutral practice, connected to power and tradition. Practitioners are said to perform rituals meant to heal or protect people, or, if inclined, for more menacing purposes, like curses.

The creation of the modern state in Liberia fundamentally altered the practice of witchcraft. According to the historian Stephen Ellis, as descendants of the freed American slaves who founded the country came into contact with rural societies, they encountered traditional religious practices, and over time a kind of melding of cultures occurred. Some aspects of the occult became monetized, as practitioners with a reputation for skill began offering their services in exchange for pay and influence. In some cases, rituals requiring human blood or body parts were among the services on offer.

Before the war, a popular belief connected ritual killings to Liberia’s influential and secretive Masonic Society, an import brought by the former American slaves. For many years, membership in the Masonic Society was a prerequisite for participation in the highest strata of Liberian public life, and its opaque and elitist practices became associated with the exclusionary politics that eventually drove the country to war. Upon taking power, one of the first acts of Samuel Doe, the rough-hewn non-commissioned officer who overthrew the Liberian oligarchy in 1980, was to ban membership.

Today the practice of ritual killing is rare, but widely feared—and suspected—by the Liberian public nonetheless. In fact, the relatively recent historical record shows that these fears are not just sane, they are in fact rooted in very public experiences, as a dramatic episode involving some of the nation’s most high-profile elites reveals.

In the mid-1970s, a group of senior public officials in southeastern Liberia was tried for the ritual murder of a fisherman. These were no mid-level bureaucrats. The investigation implicated the equivalent of a state governor and a US congressman, among others. Both were members of the Masonic Society. They were ultimately convicted and hung, on the orders of then-President William Tolbert.

According to Bowier, ritual killings are less common now, but they still happen. Sitting in the sun-bathed courtyard of his house in Monrovia, he shares his belief that the high stakes at play in this year’s elections are likely to provoke more killings, as some candidates look to gain any edge they can. He looks to have had a point. In the late summer, protesters in Gbarnga, a key city in central Liberia, marched to demand answers over a spate of young women who turned up dead and missing body parts. One was only 12 years old.

“It’s like how we pay a mortgage every month, they pay mortgages to their power,” says Bowier. “This is why the killings won’t be only one time. Every year or whatever period of time, you will have to make a sacrifice to that god on that shrine.”

***

Jacob Vambo now resides at the Sanniquellie Central Prison, a high-walled compound about an hour’s drive from Ganta. He was tried as an adult, although he and his attorney insist he was only seventeen at the time of Cephus’s murder. In February 2016, he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Jacob is lanky, with a slight frame and a soft face that makes him look even younger than he is. It’s hard to picture him overpowering and killing someone. Jacob isn’t well; his time in prison has made him ill, and he coughs frequently when he talks. But when he tells his story, he’s forceful and clear.

According to Jacob, the murder was carried out on behalf of a senior member of the Liberian government named Sam Kehleay. It’s an incendiary accusation, but he’s repeated it consistently since he confessed. Kehleay is the county coordinator for the Ministry of Agriculture, an important position in a region that’s historically been known for its farming prowess. Kehleay is well known in Ganta, and his father-in-law is Francis Kporpor, the Chief Justice of Liberia’s Supreme Court.

Jacob says he first met Kehleay in the summer of 2015 while working as a security guard at Star Bar, a local nightclub. Jacob would park and watch over his jeep, and Kehleay took a liking to him, calling him “small security.”

“After a few months, he asked me who was supporting me and if I was a student,” Jacob recalls. “He said I was too small to be a security guard.” That night, Kehleay gave Jacob a ten-dollar tip as he was leaving the club, which he says he spent on drinks for his coworkers.

Over the next few weeks, Jacob claims, Kehleay struck up conversations with him, asking what he wanted out of life and offering at one point to help him pay for university. One night, Kehleay invited Jacob to sit with him. He ordered a round of drinks and brought up Jacob’s future again, saying that he could bring him to Monrovia and find work for him. But he said he needed a favor.

“He said, ‘I want you to do something for me,’” Jacob recalls, sitting in the cramped, muggy office of the prison warden. “I need some parts from a human and I would like you to find someone for me.”

Jacob says he was shocked and didn’t know how to respond. When Kehleay noticed Jacob’s apprehension, he said to him, “Plenty things make a man.” He assured Jacob that he didn’t have to worry because he had “backing in the government” and would protect Jacob if there was any trouble. Kehleay said it “wasn’t compulsory” and that he shouldn’t be afraid. A few nights later, Jacob says Kehleay slipped him $45—a large sum for a young Liberian.

In mid-September, 2015, Jacob says, Kehleay came back to the club. The last few visits he hadn’t interacted much with Jacob, but this time he pulled him aside. Jacob says he brought up registration fees for university, offering to give him the money if he came to pick it up from Kehleay’s house in a nearby town the following day. When Jacob’s shift ended, he claims that he saw Cephus riding his motorcycle and flagged him down, explaining that he’d be paid once they reached their destination.

According to Jacob, Kehleay wasn’t at home when they arrived, but his daughter said she’d been left with instructions to direct him to their family farm down the road. The two rode toward the farm, but couldn’t find Kehleay there, either. Since Jacob’s family owned a sugar cane patch on the same road, he suggested to Cephus that they stop to cut some stalks to sell in Ganta. He says Cephus parked his motorcycle on the side of the narrow dirt road and the two of them walked into the patch and sat down in the shade.

Not long after, Jacob claims, Kehleay entered the patch with two men in ski masks. He says that Kehleay must have been searching for them when he saw the motorcycle parked on the road. The two men were muscular, with strong physical builds. “Sam pointed me out to them, and they attacked Cephus,” Jacob says. “One of them hit him with a stick and the other stabbed him in the neck with a knife.”

Jacob claims that he hadn’t known he was carrying Cephus to his death, and says he was shocked by the brutal attack. In his telling, he ran out of the sugar cane patch, jumped on Cephus’s motorcycle, and sped back to his home in Ganta, leaving the brutal scene behind him. After a few panicked hours spent trying to gather his thoughts, he decided he had to talk to Kehleay, so he returned to his house. On the way, he says a black jeep and white pick-up truck passed him on the road.

When he reached Kehleay’s house, Jacob says he was admonished for running away. Had Jacob seen the jeep and pick-up on the road? “Those were your comrades,” Kehleay said. “I wanted to introduce you to them.” When Jacob said he was uneasy about what had happened, Kehleay repeated the phrase he’d used weeks earlier in the club: “Plenty things make a man; you don’t need to be afraid.”

Jacob says he was racked with guilt. As night fell, he resolved to confess what had happened to Cephus’s mother. But when he arrived at their house, he hesitated, instead asking if Cephus was home. When Cephus’s brother and friends confronted him, he ran away. The next morning he was arrested.

For the next three days, Jacob says, he was beaten by police officers. At first he remained silent, waiting for Kehleay to make good on his promise and rescue him. But when Kehleay didn’t show up, Jacob started talking. His interrogators had threatened that he’d be raped in prison, so in his first confession he claimed his brothers had helped him kill Cephus on Kehleay’s behalf. He says he thought they’d protect him if they were imprisoned as well. Investigators rushed to arrest Jacob’s brothers but were skeptical of his claim about Kehleay.

Nonetheless, they invited Kehleay to the station. When he arrived, he was brought into a room with Jacob and Zbeghn. Kehleay denied Jacob’s story and said that he’d never met him before.

“I was angry,” Jacob says. “I told them I had witnesses that could prove we met in Star club.” Before leaving, Jacob says he saw Kehleay write something on a sheet of paper, fold it up, and leave it on the desk of the chief investigator. That was the last time he saw Sam Kehleay.

A few months later, Jacob was tried for murder. While cases in Liberia often take years before they are brought to trial, Jacob’s case moved through the system with rare speed. A public attorney was assigned to defend him, but a jury found him guilty. At the end of February 2016, he was sentenced to life in prison.

“I told the court that I’ve committed a sin in front of my heavenly father,” Jacob says. “I beg for forgiveness from God for taking Cephus to that area. I’m not saying I don’t deserve punishment, but let justice prevail for Sam also.”

***

The story Jacob tells is detailed, but without witnesses or evidence to back it up, it’s impossible to tell how much of it is the truth. There are good reasons to be skeptical. Kehleay would have been taking a huge risk to bring a teenager he barely knew into a violent conspiracy, and if Jacob was so upset by the murder, why didn’t he go to the police straight away? Also, if what he says about Kehleay is true, it’s hard to imagine that he had no inkling of what might happen to Cephus after Kehleay’s daughter pointed them toward the farm.

Jacob also hurt his credibility by initially accusing his brothers of helping to murder Cephus. The next day he recanted, telling the version of the story that he’s stuck to since then, but it doesn’t make him look reliable. His brothers were tried along with him but acquitted. In their testimony, they attributed Jacob’s false statement to a family feud and said they’d kicked him out of the house earlier that summer.

But the behavior of the Liberian police after Jacob’s confession is far more troubling than the inconsistencies. His brothers were arrested within days of the confession, but Kehleay was barely investigated at all. His house wasn’t searched; he was never formally interrogated, and there’s no record of the police attempting to track down the witnesses that Jacob said could place the two of them together at Star club.

“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark,” says Mewaseh Paybayee, Jacob’s public defender. “If a suspect is named, he should be investigated. The police didn’t do well.”

Paybayee also points out that Jacob’s size would have made it difficult for him to inflict the kind of damage that was done to Cephus’s body. “He doesn’t have the strength to kill that person on his own. It’s an organized crime.”

Armstrong Wonleh, a police investigator in Saniquelle, a city north of Ganta where Jacob was tried, says that they looked into Kehleay but there wasn’t enough evidence to charge him with a crime. “Sam Kehleay said he doesn’t know Jacob. If you don’t have probable cause, how can you charge a person?” He adds that police couldn’t find Jacob’s witnesses. “Those people don’t work in the club anymore, so their whereabouts are unknown.”

But two of the witnesses Jacob named in court live within walking distance of the club, and neither was difficult to locate. One, a young waitress named Massa, says she served so many people that summer that she can’t remember if she saw Jacob and Kehleay sitting together. The other, a security guard, also says he can’t recall seeing the two of them interact. A bartender who works at the club does remember Jacob buying a round of drinks for the staff one night, which he said was strange given his meager salary. But none could conclusively back up Jacob’s story.

All three said the police hadn’t interviewed them. Contrary to Wonleh’s account of their disappearance, any of them could have been located in a matter of hours. But by now, enough time has passed that their memories of the events leading up to Jacob’s arrest are cloudy, and their value to an investigation is less than it would have been immediately after the murder. Their names also became public during Jacob’s trial. If anyone had cause to tamper with, bribe, or intimidate them, they wouldn’t have been hard to find.

And what of Kehleay’s daughter, whom Jacob says directed him to the area where Cephus was killed? According to Wonleh, she was never even interviewed. “The thing about Sam’s daughter being involved, I don’t have any knowledge of that,” he says.

The facts surrounding Cephus’s brutal murder are now unlikely to ever be definitively established. But it seems clear that Kehleay’s elite status helped insulate him from the kind of scrutiny and investigation that Jacob and his brothers were subjected to.

Wonleh says Jacob isn’t reliable, and that he thinks he made up the story about Kehleay. If Wonleh is right, Jacob is a gifted storyteller. His account of Kehleay’s involvement includes a series of specific events, sums of money, and small details, like the types of vehicles that passed him on the road and the “small security” nickname. At the very least, it’s hard to understand why the Liberian police didn’t spend more time trying to determine whether Jacob was telling the truth, especially given the brutality of the crime.

In person, Kehleay is heavyset, with a deep, raspy voice. He’s been gardening in his compound, and swats at flies buzzing around his head. When questioned about Cephus’s death, he asks, “What did the police say? I don’t want to glorify rumors.” He claims to have never met Jacob and that making false accusations is just “some people’s way of life.”

Kehleay says he didn’t follow the case in court and knows nothing about the murder. He makes sporadic, brief eye contact as a young woman pulls up weeds in the garden behind him.

“Nobody paid me to call [Kehleay]’s name,” Jacob asserts. “He’s not the only big person I know in the county. I’m a security guard, I know people much more important than him. Why would I call his name?”

***

The written statement of the chief investigator in Jacob’s case is dated September 29, 2015. The following morning, Ganta erupted into one of the worst riots in Liberia since the end of the civil war, after another motorcyclist turned up dead. The town was already on edge over Cephus’s death, and when a rumor began to circulate that the motorcyclist’s body had been drained of its blood on behalf of a wealthy businessman, the city erupted into chaos.

The rumor was later disproved, and the death was credibly attributed to a botched robbery attempt, but not before the local police station was ransacked and the businessman’s properties set ablaze. UN peacekeeping troops and Liberian police paramilitary units were deployed to Ganta, and in the wake of the riot, two were found dead and fifty were arrested.

“It was like wartime,” says Leslie Duyea, a reporter with one of Ganta’s radio stations.

The riot was a stark display of the tensions that exist in a traumatized country, not long removed from the experience of war, where many don’t know whom to trust for information or protection and an underpaid and poorly motivated police force are either unable or unwilling to protect the country’s citizens. Ritual killings are an extreme example of the insecurities that Liberians face on a daily basis. But the killings are indicative of a worrying dynamic that extends far past Liberia’s borders: When the powerful are seen as predators that cannot be brought in check, what loyalty does one truly owe to the state?

In July 2016, the UN peacekeeping mission formally handed over security responsibilities to the Liberian government for the first time since its civil war ended, thirteen years earlier. But many people in the country are nervous over the prospect of security forces long associated with corruption and violence resuming their authority.

The assumption underlying the handover is that Liberia’s police are capable of fairly enforcing the rule of law. A lack of accountability for elites and unequal justice for the poor were huge factors in Liberia’s catastrophic unraveling in the 1990s. Now, there’s an active civil society and press in the country, and a great deal of money and energy has been spent by donors and the government in efforts to establish a fair justice system that works for all Liberians. Jacob’s case suggests that this has not yet come to pass.

“Ritualistic killing is a difficult thing to fight,” says Sam Kingsford Collins, spokesperson for the Liberia National Police, “because you likely won’t know the doer.” But Jacob’s case indicates that even when police have a lead on a suspect, they might still escape justice.

All of this calls into question what lies ahead for Liberia, in a year when so much is at stake. Liberians went to the polls on October 10th to vote for a successor to President Johnson-Sirleaf, in an election that observers hope will see the first peaceful transition of power between administrations in nearly fifty years. Allegations of election fraud have put a stop to the process, with a runoff between former football star George Weah and current Vice President Joseph Boakai now suspended pending an upcoming supreme court ruling on the legitimacy of the first round of voting. The court case can be read as a sign that the rule of law is functioning as it should in Liberia, but it’s also raised fears that an eventual handover will be marred by hurt feelings and suspicion. Regardless of who becomes the 25th president of Liberia, the blue-helmeted United Nations peacekeepers who draped a psychic security blanket over Liberia since 2003 are essentially gone, and a new era for the country is fast approaching.

Ultimately, the events in Ganta last summer are less about a rare and bizarre occult practice than a troubled justice system. Whether or not Kehleay is guilty, the failure by police to thoroughly investigate him points to a lack of competence, or worse, a willingness to help powerful individuals evade the law. It’s a microcosm of why Liberia’s judiciary is so widely mistrusted, and helps to explain the violent riot that took place only days after Cephus was killed.

The County Attorney for the region that includes Ganta—roughly equivalent to a US District Attorney—said late last year he was considering re-opening the investigation into Cephus’s death in the wake of attention by the press. “If we have a prominent person committing a crime, the law will take its course, we can assure the public of that,” he says. “But we can’t make sweeping statements until the police investigate. We prosecute, not persecute.”

Given the length of time that’s passed since the crime, it’s unlikely that new evidence will turn up. As Liberians look hopefully toward the dawn of a new period in their history, Jacob remains in prison, Kehleay is still on the job, and James Zbeghn has lost his son.

“There is no justice in Liberia,” Zbeghn says. “This is the reason why mob violence happens. They can kill my son, but God’s judgment is before them.”