Since the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began investigating Communist influence on the film industry in 1947, the Hollywood blacklist has performed various cultural functions. An early and unusually open volley in the cultural Cold War, it first served to pry apart the Popular Front and to signal that in the post-war era, Communism would have no acceptable place in American life.

Later it was, along with much of the rest of the second American Red Scare, stripped of its real politics, and restaged as a First Amendment morality play, one that would allow liberals to condemn McCarthyite excesses without having to acknowledge the significant role Communists had played in the development of twentieth-century American popular culture. Here, the blacklist could both stand as the exception that proves the rule of the United States’s commitment to fostering free expression, and buoy the cynicism that absolves such expression of any real political consequence.

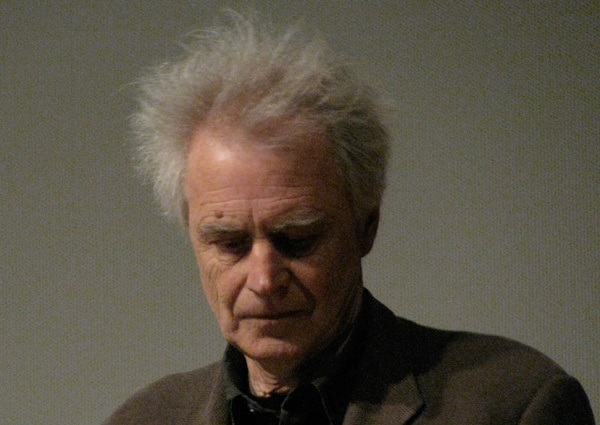

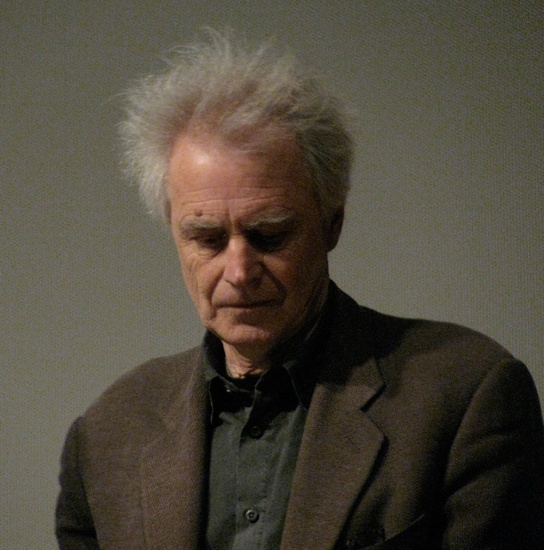

Few have done more to counter this mythology of the blacklist than filmmaker, writer, and teacher Thom Andersen. His 1985 essay “Red Hollywood” was the first in a series of what he would later describe as “fugitive and ephemeral” contributions to blacklist scholarship. Primarily historiographical, the essay is a caustic dissection of the ways commentators have employed the blacklist and its victims. Andersen savages three generations of liberal historians and cultural critics for their refusal to face the true political and aesthetic stakes of the HUAC hearings, and provides a sensitive sketch of the social forces and political goals that animated Communist screenwriters, directors, and actors.

Like HUAC, Andersen charges, blacklist historians across the ideological spectrum remained entirely incurious about the films actually made by Communists in Hollywood, assuming they lacked even the slightest political or aesthetic import. This question of the Hollywood Communists’ actual production, and the significant impact it made on American politics, has occupied Andersen’s subsequent work: the French-language book Les communistes de Hollywood: Autre chose que des martyrs and the video essay Red Hollywood (1996), both made in collaboration with film theorist Noël Burch.

Comprising clips from more than fifty films, interviews with blacklistees, and a commentary read by filmmaker Billy Woodberry, Red Hollywood shows that Communists were able to produce a genuinely radical body of popular films. Examining the output of the Hollywood Communists thematically, it reveals that these deeply committed cultural workers could not help but infuse their collaborative productions—fluffy genre exercises and self-serious prestige pictures alike—with a feeling for the everyday life of the class struggle, and, during the brief window opened by the Popular Front, the evils of fascism. As blacklist filmmaker Abraham Polonsky explains: “There was no plot to put social content into pictures…. Social content is what pictures are about. You can’t make a picture about human life without social content.”

Neglecting neither the constraints imposed by corporate mass production nor the hard-won and limited freedoms achieved by those working within the system, Red Hollywood offers a sophisticated rebuke to both the vulgar Marxism that sees a clean equation between cultural superstructure and economic base, and the liberal myth of the autonomous Hollywood auteur.

When Red Hollywood first appeared in 1996, it marked Andersen’s return to filmmaking after a twenty-one-year hiatus that he filled teaching at SUNY Buffalo and Ohio State and writing. In the years since, he has been comparatively prolific, producing a small handful of shorts, features, and mid-length works, most notably Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) and Get out of the Car (2010)—related examinations of the imagination and experience of Los Angeles, the city of his upbringing and his home again since 1987, when he began teaching at the School of Film/Video at CalArts.

Long out of circulation, Red Hollywood was recently remastered and lightly re-edited for theatrical tour and home video. Its reappearance is timely. In his book The Cultural Front, Michael Denning observes that the foreclosure of the Popular Front put an end to its mass-cultural elaboration of the “labor metaphysic” that artists on the left had shared with audiences throughout the ’30s and ’40s: “the assertion of the dignity and beauty of working-class arts and entertainment; the alliance between unions of industrial workers and unions of artists; the defense of arts and crafts in the face of commercial exploitation; and the profound sense that the dialectic between work and art, labor and beauty, was fundamental to human culture.”

In the wake of Occupy, and in the face of disappearing funds for cultural work of any kind, such labor theories of culture have found a new currency among a generation of politically engaged artists and viewers. These people demand a heartier cultural politics than the Rancierian alibis and shallow social-practice theatrics offered by the art world, which the knee-jerk auteurism of official film culture does not even pretend to provide. Red Hollywood supplies a foundation for a more useful tradition of political aesthetics, rooted in the mass party and circulating as mass culture, and participating in a mode of resistance that doesn’t need to be discovered against the grain or from within the cloister.

—Colin Beckett for Guernica

Guernica: When did you start seriously thinking about the Hollywood blacklist?

Thom Andersen: I grew up in Brentwood, a part of West Los Angeles, during the 1950s. Many of my friends then had parents working in the motion picture industry. The blacklist was something in the air, but something that wasn’t talked about. So I was naturally curious about it. I read the only book I could find about the blacklist, John Cogley’s Report on Blacklisting. I agreed with his criticism of the House Un-American Activities Committee, but, as I recall, I found the analysis of the films of blacklist victims written by [film critic] Dorothy Jones crude and overly schematic. I was an anti-Communist—how could I not be growing up in the 1950s?—but I never felt any passion for that cause.

The films of the blacklist victims were dismissed and the cultural impact of the blacklist was ignored.

I became what we called a “radical liberal”: I got my news from I. F. Stone’s Weekly—when I was young, everyone read it, even Howard Berman, who later represented part of the San Fernando Valley in Congress. You wouldn’t think of him as a radical. I was against the House Committee and the Taft-Hartley Act, I supported Hubert Humphrey and then Adlai Stevenson against John Kennedy in 1960, I helped to pack the galleries at the Democratic Convention in Los Angeles for Eugene McCarthy’s nomination speech for Stevenson. During the year I spent at UC Berkeley [1961-62], we Democrats found ourselves allied with the Communists against the more radical Trotskyists. But then I transferred to film school, and politics receded in my mind.

I think it was the publication of Victor Navasky’s Naming Names that made me think more about the blacklist. The book was unnecessarily vicious, and it explained little. There was absolutely no political content. He really tried to eliminate politics from that book and turned everything into morality. And once again, the films of the blacklist victims were dismissed and the cultural impact of the blacklist was ignored.

Guernica: When did you start moving further left? It’s clear that, though you didn’t identify as a Communist, you were approaching things from a materialist standpoint by the time of the essay “Red Hollywood.”

Thom Andersen: Maybe I was always a materialist in my way. At the time of the essay, I also felt a sense of disgust at the nouveaux philosophes [the philosophers who broke with Marxism in the early 1970s] in France. I actually first learned about them through this film Solzhenitsyn’s Children…Are Making A Lot of Noise in Paris (1979), a documentary Michael Rubbo made for the National Film Board of Canada. I felt kind of like: These people need Solzhenitsyn to react against the left?

In the United States, anyway, anti-Communism was something we had kind of always already known, and we were moving away from it. Communism didn’t have any influence on people my age. In that light, the nouveaux philosophes just seemed kind of silly, sanctimonious, and full of themselves.

Guernica: “Red Hollywood” seems to me to contain a fuller-throated defense of the contributions of American Communists, if not the CPUSA itself.

Thom Andersen: I think it’s more anti-anti-Communist than it is pro-Communist. I suggest that the Communist Party was in the tradition of the American left and not a foreign body in the way that people liked to regard it even at the time I wrote the essay.

Guernica: You also deny that they were “liberals in a hurry,” as you suggest Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund paint them in The Inquisition in Hollywood.

Thom Andersen: That’s not the right way to put it, but on the other hand, pretty much everything they advocated that seemed radical and extreme in the ’30s and ’40s, during the Popular Front, is now part of the mainstream of liberalism, except their defense of the Soviet Union. Their only position that hasn’t been taken up by mainstream liberalism is their black nationalism—that is, the notion that blacks in the South should form a separate nation. I guess my position was evolving. I probably didn’t get interested in Marxism until the early 1970s.

Guernica: How did that happen?

Thom Andersen: It wasn’t really through experience since I wasn’t among the people in Los Angeles, radical filmmakers and others, who decided to support the “back to the factories” movement, mostly autoworkers. That didn’t appeal to me at that particular time.

I think my interest in Marxism started with EP Thompson. I read all of his books that had been published then. I started with The Making of the English Working Class, but the one that left the most permanent impress was his 1955 book on William Morris, who was also an artist as well as an agitator and propagandist.

Guernica: I would have to imagine that another contextual influence for you, writing “Red Hollywood” in the mid-’80s, was the sharp rightward turn in Hollywood movies that accompanied the Reagan era.

Thom Andersen: I probably didn’t really understand Reaganism yet when I was writing it. This period was a tempestuous time for me politically because of politics internal to Ohio State University. There was a struggle within the department of photography and cinema, of which I was a part, between the old guard and new guard. The guy who was the chair at that time, Ron Green, was young and didn’t have a lot of academic experience. I think his appointment was controversial even though he wasn’t aware of that. He thought he had a mandate to completely change the department. The first people that he hired were me and Klaus Wyborny [the German-born scholar and filmmaker], who left after a year, was replaced with Noël Burch. And the next person hired after that was Allan Sekula [the American academic and filmmaker].

Quite a number of people were involved in the Committee in Solidarity With the People of El Salvador, which was a big political cause at the time. There was a photograph of Allan in the local paper, The Columbus Dispatch, wearing a Ronald Reagan mask and burning money. That was the end. It turned the dean against Ron Green.

So there was this purge. Allan, myself, and James Friedman, a photographer who wasn’t political at all but was associated with Ron Green, were all denied tenure. It would have gone smoothly enough except one of the old guard kind of got freaked out when another faculty member said to him, “We gotta get rid of the Jews and the Communists.” It’s kind of what they did, but putting it that way didn’t make it sound so good.

That was going on when I was writing the essay, and probably influenced the writing of it, making me more sympathetic to the blacklisted people and to Hollywood Communists because I rather felt the same way. I guess I had this naïve belief that people in academia and other places would hear about this and protest, write letters to the authorities at Ohio State protesting it, but we were left exposed. Even the AAUP [American Association of University Professors], it turned out, was actually telling stuff we had told them to the other side in the department.

Guernica: When did you and Noël Burch decide to make what was initially supposed to have been a higher-budget film, and became the video Red Hollywood?

Thom Andersen: Noël would later claim it was his experience at Ohio State—or specifically, the film history class I taught—that turned him away from formalism and made him understand the political significance of film, and locate films as part of a greater, concrete social reality. But it seemed to me he had already turned away from formalism by the time he got there.

After he left Ohio State, he went back to France and made What Do Those Old Films Mean? (1985), which as far as I can remember was the first real movie to treat movies as social documents, or put them into a social context. I thought it was great.

When he later came back to the United States to teach at UC Santa Barbara, we started to work on the movie, just looking at a lot of films. There were a couple of years we spent doing research. We wrote a version of the film script in 1988, and tried to raise some money. We applied for a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, which of course had gone through this big transformation under Reagan. Back in the ’70s they had funded Seeing Red (1983), for example, and a number of films on contemporary political situations.

I didn’t think this was that kind of film. I thought it was more academic, historical. I thought of us as scholars even though we didn’t have PhDs.

It was Marco Müller, who was head of the Locarno International Film Festival, who inspired us to finish it a few years later. By ’94, it seemed feasible to make a version of the film just from VHS tapes. It was when non-linear editing systems had just become common and the school got one, an AVID. And it was actually made during the course of a summer.

Noël came out to Los Angeles and stayed with me and we figured it out from scratch. We didn’t really follow the earlier film. I don’t think we even referred to the script. We just decided to start over. The earlier film had more historical context, which I think was too much, but not enough. There are things that were second nature to us that, of course, younger people wouldn’t necessarily know anything about. So we tried to show just enough that it would make sense to someone who hadn’t lived through the period or read histories of the period. I’m not sure we succeeded.

We pay our respects to these people precisely so that we can continue policies which are completely antithetical to what they stood for.

Guernica: Why have so many mythologies about the blacklist lingered when many of their material supports have dropped away or been altered?

Thom Andersen: There’s no one alive today who defends the blacklist except for Richard Schickel [the American journalist and film critic who currently writes for Truthdig]. It’s an example of something I talked about in Los Angeles Plays Itself in relation to L.A. Confidential (1997): “History is written by the victors, but it’s written in crocodile tears.” We have a Malcolm X stamp, a Paul Robeson stamp, a Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. We pay our respects to these people precisely so that we can continue policies which are completely antithetical to what they stood for.

Guernica: It seems that on the one hand, culture and art can be anything so long as it’s not political. On the other hand, if it’s a popular art, it cannot be political enough. It doesn’t fulfill whatever criterion might be taken for the left—what you term the perceived “double moral corruption” of the blacklistees.

Thom Andersen: Well, I tried to show that the liberalism of Hollywood is superficial and there’s a deeper ideological current that is profoundly conservative.

Robert Duvall was once asked how he got along as a conservative in Hollywood. He said: “…name me one black or Hispanic head of a studio or agency. So, how liberal is it out there in Hollywood, really?”

The motion picture industry is an industry which, better than any other, has resisted integration, or even making a place for women. Every year, the percentage of women directors in Hollywood drops. Every year, the percentage of women writers in Hollywood drops.

Guernica: One of the things that’s interesting to me about the blacklist is that, in the larger context of the cultural Cold War, it follows a very different pattern than in other fields, it’s much more open. The CIA doesn’t get involved until the mid-’50s—Congress intervenes instead.

Thom Andersen: I’m not sure the anti-Communist films were that significant. I think most of them didn’t have a lot of conviction behind them, except maybe Elia Kazan’s. There was a turn to the right in Hollywood in the 1950s, but the fact that a number of anti-Communist films were made is only the most superficial aspect of that.

I guess another one that was made with a sense of conviction was My Son John (1952). It’s actually, I’d say, quite a profound film about what happens in a working-class family when the son goes away to college and his values become very different from those of his parents, which is not something that necessarily has to do with Communism per se. It’s a much broader subject, and I think My Son John is the only film that considers it.

Guernica: One difference between the film Red Hollywood and the essay is that the structure of the film is more dialectical. There’s a lot of disagreement between what might be seen as your and Noël’s initial line—as presented in Billy Woodberry’s narration—and some of the interviews themselves.

Thom Andersen: You could say that we tried to allow the films to speak for themselves without making too many claims for them or judgments about them, aside from taking them seriously, and having a sympathetic view of the political project behind the films. There’s a lot less didacticism than in Los Angeles Plays Itself, certainly. Although I think if someone went back and read [the Polish-American Communist writer and editor] V. J. Jerome’s little pamphlet “The Negro in Hollywood Films,” they would agree with his criticism of the films for sure.

It was tempting to say that Paul Jarrico [the blacklisted screenwriter and film producer, who is featured in the film] was wrong. That is when he says, “If someone was going to rescue these people, who would it be except for some liberal white Southerners? It wouldn’t be the Black Panthers.” One could have said, “Well, it could have been the Communist Party.”

Guernica: The whole “Race” section of Red Hollywood is really interesting. It’s the only way in which the politics of the films by Hollywood Communists are wholly unsatisfactory.

Thom Andersen: That’s why I think it’s important to have the quotations from Jerome, because one might say it’s a matter of judging something by standards that didn’t exist then. Just as some people defend The Birth of a Nation by saying that it’s just what people thought back then, which is an ahistorical way of looking at it.

The American left today has decided to devote itself to causes it can win, like gay marriage, bicycle lanes, banning smoking.

Guernica: I wanted to ask you about the question of nostalgia. You’ve talked about some of your work as “radical nostalgia,” and much of it seems to take the cast of a classic left melancholy. You conclude Red Hollywood with a Polonsky celebration of “lost causes.”

Thom Andersen: In Ethics, [French philosopher] Alain Badiou writes that the “possibility of the impossible” is the only real principle of an ethic of truth. What Polonsky says, that the only causes worth fighting for are lost causes, is not so far apart.

What they share is a kind of rejection of the idea of politics as the art of the possible, which is a great problem of the American left today—that it has decided to devote itself to causes it can win, like gay marriage, bicycle lanes, banning smoking. Thereby turning politics into the art of the trivial, a petit-bourgeois politics, a kind of recycling.

Guernica: Red Hollywood now wouldn’t spur just nostalgia for a certain form of mass politics, but for cinema itself, which only twenty years after it was made has a radically diminished place as the standard-bearer for mass culture.

Thom Andersen: Yeah, and the development of American television from being a unanimous medium into a medium that reflects the divisions among people.

[French film critic] Serge Daney used to say that films should divide. It’s true, but the corollary of that, one could say, is that television unites, television was all about finding what was within the mainstream, as sometimes is said—what were political positions that could be accepted by everyone, what was the nature of the political consensus, and how far did that extend. It was kind of fascinating. And, of course, I guess, probably at that time, I yearned for a television that divided, but now that we have it, I yearn for a television that would unite.