Midway through his documentary television series All in the Best Possible Taste, the artist Grayson Perry visits a show home in a new residential estate in southeast England. The house is a full-scale version of the other homes available for purchase in the estate, furnished and decorated to give prospective buyers a sense of the living environment that could be theirs. The woman guiding Perry around explains that the house encapsulated a lifestyle that she felt could suit her own—so much so that she decided to buy the show home itself, and all of its contents (even the crackers in the cupboards). “It was like moving into a hotel,” she tells Perry. “All I brought was my handbag. It was all done.”

The scene exemplifies the notion of an aspirational purchase—buying into a decidedly middle-class neighborhood—but receives special focus in the show for what it says about taste. The choice to buy the fully decorated house over its identical but undecorated neighbor precludes the need for future taste decisions. Rather than coming to reflect the owner’s taste, the show home becomes the owner’s taste: a middle-class palate bought ready-made.

Perry’s artistic interests coalesce around how taste is informed by class, and his TV show is a kind of anthropological safari through the landscapes of Britain’s three taste “tribes”: working class, middle class, and upper class. As research, he trains his binoculars on rituals: primping for a night out at the social club in postindustrial Sunderland, sipping rosé while perusing Jamie Oliver kitchenwares, selecting the appropriate pink trousers for an after-polo reception. He is particularly interested in default choices, those positions and judgments made unconsciously—from hosting dinner parties and purchasing cars to simply having curtains. He doesn’t come down heavily on either side of the tastes he explores, but does critique close-mindedness and occasionally ridicules stuffy behavior. Perry’s aim is to push society to reflect on the motivations or pressures that produce their decisions. As he explains in the interview that follows, “I’m trying to do therapy on the whole society, by saying, ‘Here’s what you’re like. If you like it, great. If you don’t, you can change it. But if you don’t know that’s what’s going on, you’re stuck with it. You’re a victim of it.’”

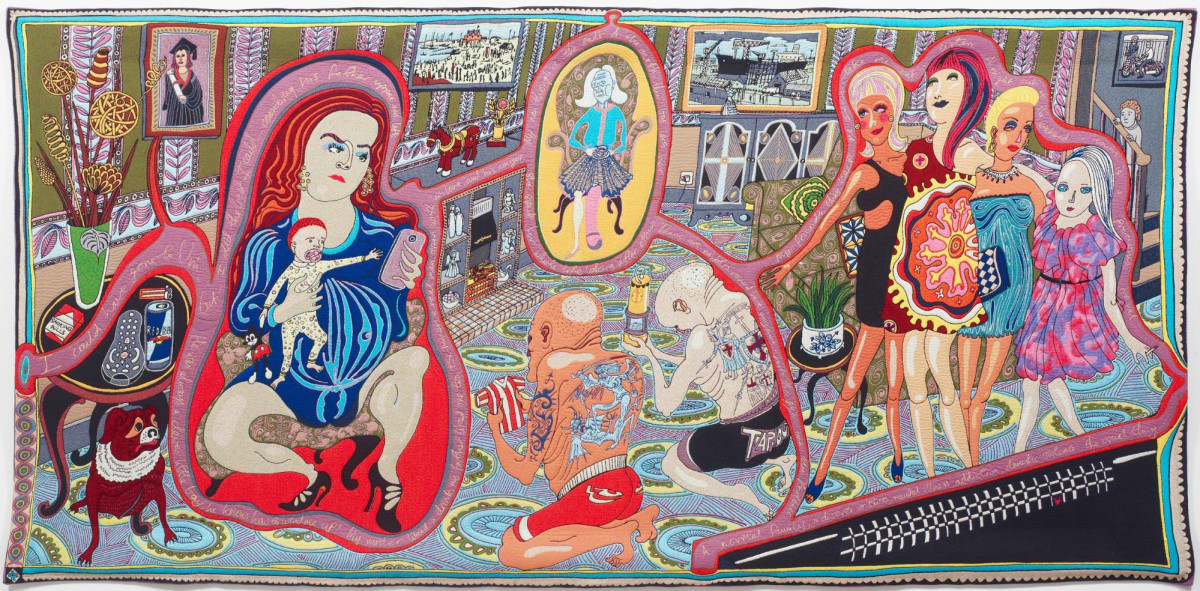

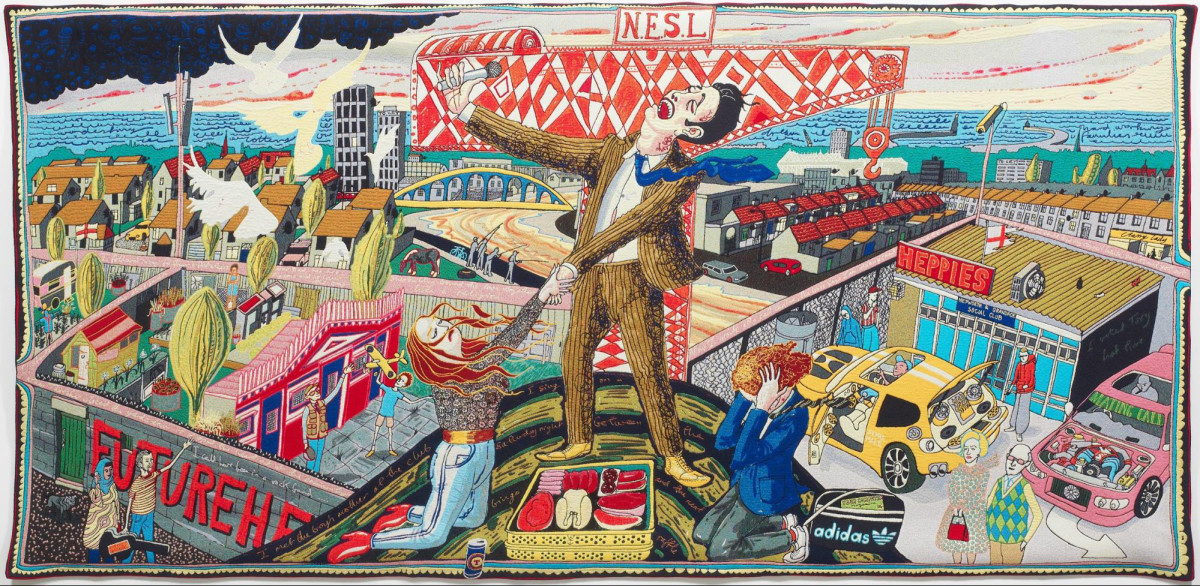

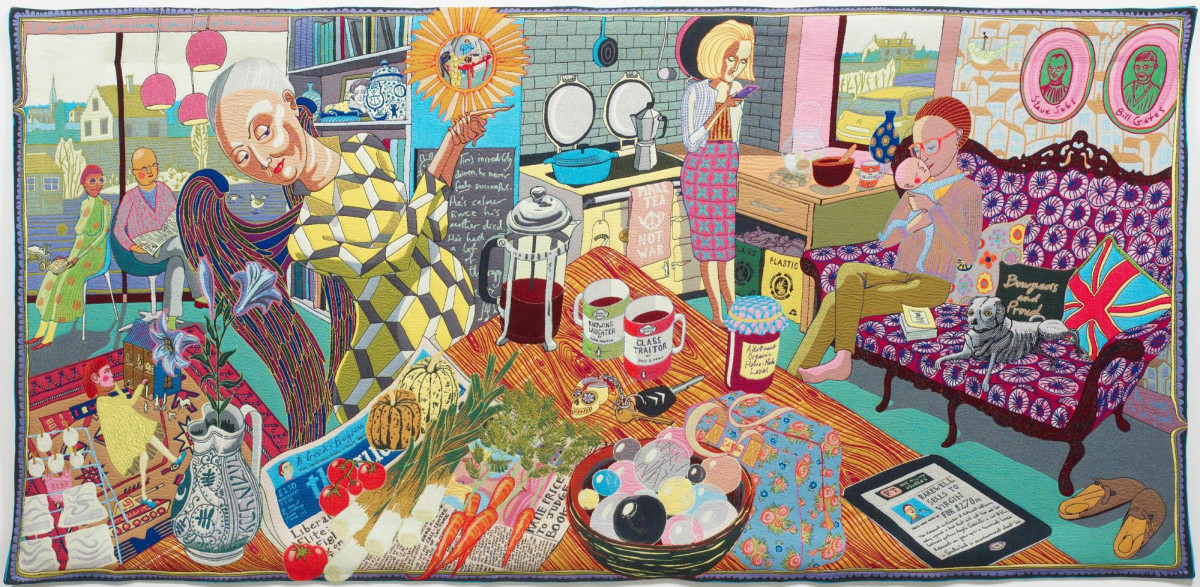

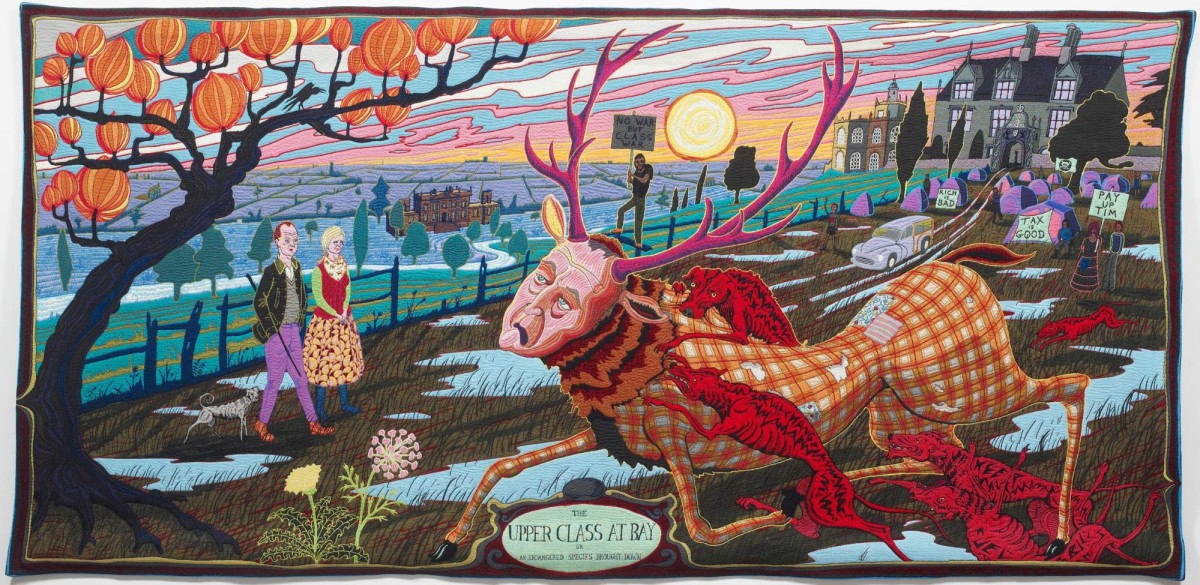

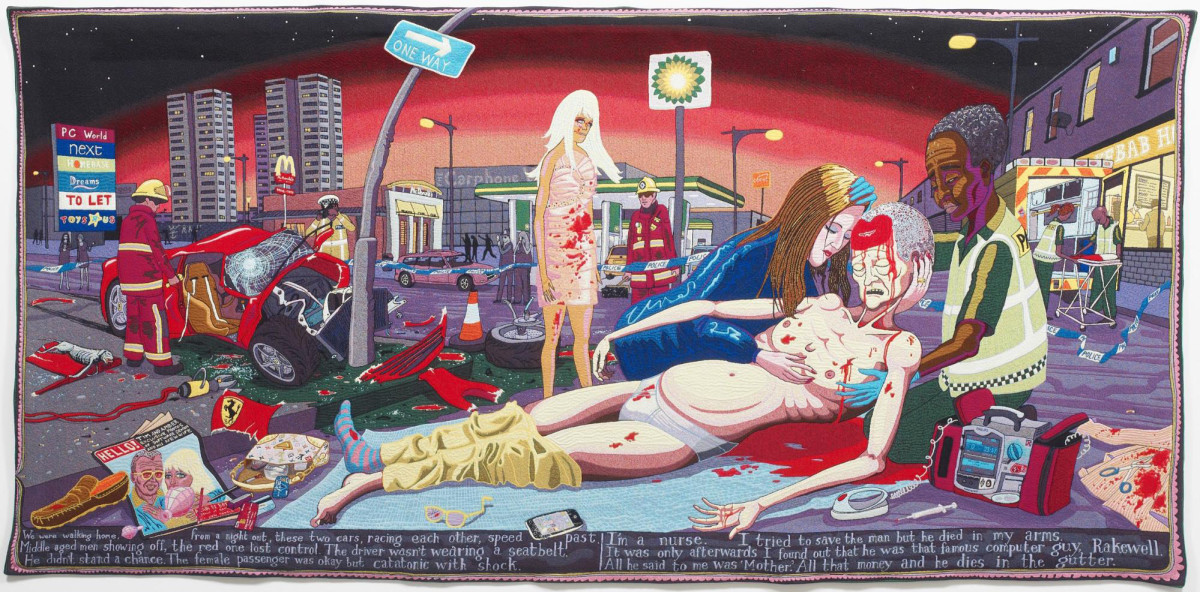

Navigating these territorial and often peculiar tribes in class-anxious Britain is no mean feat, but Perry has an uncommon combination of background, credibility, and frankness that jells across class lines. He grew up in a working-class family in Essex, and as a teenager realized he was a transvestite. With the encouragement of his school teacher, he went to art school, and found pottery his medium. He was awarded Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize in 2003 (he retains the distinct title of being the only transvestite potter to have won), and has curated a show of his own works alongside objects made by unknown people throughout history at the British Museum. In 2012 Perry’s documentary observations of class and taste were spun into six huge tapestries entitled “The Vanity of Small Differences,” a modern-day interpretation of William Hogarth’s morality tale “A Rake’s Progress.” And last month saw the release of both a new television show, Grayson Perry’s Dream House, in which he fulfills his dream to build a secular temple in Essex, and the publication of his latest book, Playing to the Gallery: Helping Contemporary Art in Its Struggle to Be Understood, which probes taste and comprehension in the world of contemporary art.

Each year, Perry hosts a competition in which students at London’s Central Saint Martins art school are asked to design him a dress. The criteria: the dress must be as unfashionable as possible. When we met in New York last month, Perry was wearing one of the winners, a vivid yellow frock covered in twirling teacups. It was the most colorful item in the boutique hotel in which we sat. (“Between you and me, they kind of tend to all look the same,” he confided.) Our conversation took in the objects (for the middle class, the ubiquitous French press) and telltales of taste, the damaging effect of the Internet on the germination of culture, and how the posher you are the less you have to prove.

—Henry Peck for Guernica

Guernica: Where does taste begin?

Grayson Perry: Well, taste is a phenomenon. Most of taste is unconscious—it comes from your upbringing, from your family, from your society, your gender, your race; it’s a melange of all those things. The basic premise of taste, as Stephen Bayley, the cultural critic, said, is that taste is that which does not alienate your peers. Most people want to fit in with their tribe in some way or another, so they give off signals, whether it’s with their clothes, their behavior, their car, their whatever, and gain status. Every tribe has a hierarchy, and that’s what taste is: it’s an unconscious display of who you are, and where you want to be.

Guernica: What was the taste landscape of your childhood?

Grayson Perry: I come from a working-class family in Essex, which is like the New Jersey of Britain, if you like. I grew up in a house that had no books. None at all. Not really any music, and certainly no paintings. We watched the television. Being from Essex a lot of our roots would have been in the East End of London, so real old-fashioned working-class culture—singing songs, going to the seaside and eating fish and chips and sitting on the beach. I never went to an art gallery until I was sixteen—it was part of my O Level course. Art for me was always something you did, it wasn’t something you looked at.

Guernica: In Playing to the Gallery, you describe a significant moment of realization in a childhood art class. Can you recount that?

Grayson Perry: That’s going right back to when I was in primary school. We had a pottery lesson and I was misbehaving so they put me at the girls’ table, which was like the ultimate punishment, but for a transvestite it probably keyed into something. I was a formative transvestite; I didn’t know I was a transvestite at that point. I had to wear this blue plastic smock, and I just remember getting my first twinges of sort of fetishistic sexual pleasure from a teacher snapping me into the PVC smock. And also a slight feeling of humiliation, which is an amazing aphrodisiac. And then also making a pot. So maybe there’s a confluence of things going on that have some bearing on my later life… That’s my creation myth, if you like.

You have to reach the terminal velocity where you go through the sound barrier of self-consciousness, and then pop out the other side where you’re confident enough to handle it.

Guernica: Looking at the three class taste tribes you trace in the TV program (working, middle, upper), it struck me that working-class taste and upper-class taste share certain qualities—namely, a sense of nostalgia and holding on to a past identity—while middle-class taste seems to not.

Grayson Perry: There’s a desperation in middle-class people to try to be individual. I think it’s an illusion on the whole, because curiously they all end up being an individual in the same way. Because not many people are creative, really. They’re kind of individualistic but within a very narrow bandwidth of what is acceptable at the time in fashion, or what they’ve seen in magazines. Genuine maverick taste is quite rare. Say someone chooses their tattoo, right, they have a tattoo. They’re a groovy person and they have a tattoo. The real decision they made was to have the tattoo. It’s not what the tattoo is. All tattoos are basically the same. But it’s having the tattoo. They all mean the same thing, the tattoo. What is on the design is bollocks. It’s squiggly blue lines that you have on your arm.

It’s always the default position I’m interested in, the things that people do without considering it. The fact that they’ve chosen to have curtains. Middle-class people, in Britain, anyway, tend to be the intelligentsia; they’re well educated, they’re very aspirational, they’re very anxious because they’re looking down thinking, “Am I going to go that way?” or they’re looking up saying, “Oh, I’d quite like a bit of that action.” They’re the most self-conscious about it, and best informed.

Guernica: How conscious are domestic choices?

Grayson Perry: Your bobos [bourgeois-bohemians], they all agonize over their kitchen work surfaces, which is one of the epicenters of taste in the middle-class home. One woman told me, very proudly, that her kitchen work surfaces were recycled chemistry benches. And I thought, “Wow. That’s a cliché and a half to deal with.” She could name the paint shades in all her rooms as well. And the most middle-class moment was when we went up into her bedroom and I looked at the curtains, and they were sort of off-white sheet material, and she said, “Oh, they’re not curtains. They were dust cloths I had made into curtains.” And I said, “Wow, that’s the most middle-class thing I’ve ever heard. Not only are you using dust cloths as curtains, you told me you’re using dust cloths as curtains.”

Guernica: You note how a lot of effort goes into making aesthetic choices appear individual and distinct, when they are actually studiously self-conscious.

Grayson Perry: Self-consciousness, I’m very interested in that. To be creative, you need to be unselfconscious. It’s like the sound barrier when you’re an art student. You have to reach the terminal velocity where you go through the sound barrier of self-consciousness, and then pop out the other side where you’re confident enough to handle it. A lot of people never make it through and that’s a real block to being creative. You’ve got to not give a shit.

Guernica: Moments in your show convey self-righteousness in taste. How do people use taste to demonstrate their morality?

Grayson Perry: Well, the British middle class particularly want to appear good people. In the past they would have gone to church, or they would have done good works for charity, or whatever. Now, you do organic, and you recycle. Mainly it’s lip service to green issues. Because the greenest thing you can do is nothing. The greenest things you can do are: a) not have children, and b) don’t go anywhere and don’t buy anything. Of course that will be an anathema to the middle classes. So it’s a sort of superficial morality on the whole, having an allotment full of vegetables that you probably never get round to eating because there’ll be too many all at once.

Guernica: You make a distinction between displaying cultural capital and being showy with your money, but isn’t it all about consumption, fundamentally?

Grayson Perry: It’s all about status. Cultural capital is something you accrue, and it’s a subtle thing. Middle-class people in particular are more aware of it. They want the culture they consume to sort of rub off on them somehow. A big part of culture is to be seen to be consuming it. Just having art in your house. The Kindle has sort of ruined the status of reading, showing off what book you’re reading on the train. I was talking at the Met [recently] about the fact that when I made the tapestries to go with the show, I put loads of art historical references into the tapestries, because that will give a chance for all the middle-class people who come to the show to show off their knowledge. They can say, “Ah, that’s a Carlo Crivelli, and that’s a Hogarth reference, and that comes from a van Eyck,” and stuff like that. They want to be the best, and it panders to that. It’s like the knowing laughter in the difficult art-house film where some reference is made. You’re watching The Great Beauty, or something: “Oh, yes, that relates to some older film! Ah ha ha ha ha. Did everybody hear that? I understand that.”

Guernica: What determines the shelf-life of taste?

Grayson Perry: Capitalism will push it on and make you buy more stuff. We’re not in a folk culture anymore where you weave your own smock or whatever, so there’s a constant driver. It’s so sophisticated now, the way that things are sold at us. All that sort of tipping-point stuff. I’m sure they do it with huge awareness, how to implant a brand or a certain item into the consciousness of the buying public. How we feel that we are being authentic but in fact it’s all being manipulated. That’s what I feel. And I think the only way you can step out of it is not worry about being fashionable. It’s my dread to be fashionable. I tell the students when they design my clothes, for god’s sake don’t do anything fashionable for me, because then I won’t be able to wear it next year. Because it will have the signifiers on it: a certain detail or cut or image and that will be very dated.

In the working-class community, the shipbuilding and the coal mining had gone, but the emotions are like supertankers, they take ages to turn around.

Guernica: But if you’re unselfconscious, why are you concerned about being unfashionable?

Grayson Perry: I’m concerned with not ever being fashionable.

Guernica: You said you don’t want to be fashionable because that implies that at some point you’ll become unfashionable.

Grayson Perry: Yeah, exactly, that’s just a purely practical thing—I don’t want to hate my dresses. Because I’m just as prone to wanting to stand out. I hate fancy dress parties. I want to be the only tranny in the room. I’m just willing to put in the effort to stand out in other situations. I don’t put myself above this situation, it’s just that it’s my job, so therefore I put a lot of effort into it that other people wouldn’t be willing to do. They wouldn’t be willing to look ridiculous, to put in the money that I put into my clothing, and the amount of time I take to get ready when I go out. It’s boring, a lot of the time.

Guernica: You focus a lot on objects, and the power of objects to convey a certain sense of identity. But where does taste manifest in behavior?

Grayson Perry: It’s manners. If you’re in the culture business, you’re not so locked in to your class, or you can have fun with it. Someone like me, I can’t really pretend to be full on middle-class because at some point I will say just one word wrong, or mispronounce a word—I’ve got a really bad habit a lot of working-class people have which is I use long words, in the right context, so everybody thinks I understand what I’m talking about. Actually, if you really pinned me down, I wouldn’t know what the word meant.

What I found in Sunderland, in the working-class community, the shipbuilding and the coal mining had gone, but the emotions are like supertankers, they take ages to turn around. The social side of it carried on, but then it was looking for something to attach itself to. One thing I’ve learned is that our emotions, we have them in our bodies, and we look for things to put them on to. I’m sure we all know someone who’s anxious, and it’s looking for something to be anxious about. It’s not the thing causing their anxiety; it’s them attaching their anxiety to the thing. And so, when you see a working-class community that has those old style bonds and needs within its structure, it then finds things like the gym. The gym has become where they literally pump iron instead of make it.

Guernica: What about how appearance reveals taste?

Grayson Perry: My wife screamed when I first came into the kitchen not wearing a shirt. Because one of the most powerful signifiers of status and class for men in Britain is how much flesh you expose. You’ve got your sleeves rolled up now, that’s almost a bit too high for a middle-class person. Your elbows are showing, normally it’d be below the elbows at the most. Never wear shorts in the street, stuff like that.

Guernica: I’m giving off telltales left and right. And these signifiers are apparent before even speaking a word.

Grayson Perry: Oh, totally. You start at the hair, their body language, you can see it in the face a lot of the time, their facial expression. A lot of working-class people think the world’s done them a disservice because they have what you call an external locus of control. They think things happen to them, they have no control over the world, so they blame the world and there’s a sort of tension.

My bible during the making of All in the Best Possible Taste was Kate Fox’s Watching the English. It’s an absolutely brilliant book. She’s an anthropologist, and she just did the English. She really, really put in the hours on it. She says that you think of youth culture as being sort of generic, almost global now. But the middle-class youth will have a more toned-down version of the extreme haircut. And they will have a cotton-rich hoodie. There are subtle things to show you they are middle class even when they’re in a gang of gray-hooded kids hanging about on the street corner. It’s amazingly pervasive.

Awareness is really important, and that’s what I try to do in my practice and in my TV. Because the minute you’re aware of something you change it. It’s basically therapy. I’m trying to do therapy on the whole society [laughs] by saying, “Here’s what you’re like. If you like it, great. If you don’t, you can change it. But if you don’t know that’s what’s going on, you’re stuck with it. You’re a victim of it.”

Guernica: How did the different taste tribes you met respond to the categorizations you were exploring?

Grayson Perry: The upper classes were slightly mystified because they wouldn’t ever publicly admit that they’re even upper class. The theory I heard was that it came from right back in the eighteenth century. The British aristocracy were terrified of revolution because we were practically the only European country that didn’t have a revolution. We had the civil war beforehand, but we didn’t have an uprising of the people against the aristocracy like other countries had. They were terrified that was going to happen, so they almost behaviorally tamped themselves down. Like, “Would you mind awfully being my slave? That’s absolutely lovely of you to be my slave, thank you so much.” And I think that kind of attitude of ameliorating how you behave and how you boss people about, and how you retain your authority, is a very, very British thing. It’s in our DNA.

Guernica: In the US, social scientists have pointed out that the “middle class” has been chipped away at over the last few years, since the financial crisis. What used to signify aspiration and the possibility of success is now associated with failure and stagnation. So as the campaign season has started, candidates are already going through linguistic hoops to avoid saying “middle class.” Instead they’ll say “Everyday Americans,” or “The People Who Work for the People Who Own Businesses.”

Grayson Perry: We had the same thing in Britain. We had “Working Families.” Kate Fox says a really interesting thing about the fluidity of class distinction. She says the big con that’s happened in Britain is that they’ve persuaded a large section of the working class that they’re middle class, so that they feel like part of the stakeholders in certain things. She interviewed a hairdresser and asked what class she thought she came from, and the hairdresser said, “Ah’m probably middle class.” So she asked, “What makes you think you’re middle class?” “Ah’m not one of those lazy chavs, benefit scrounger people.” The only thing that was separating her, making her middle class, was that she wasn’t right at the bottom of the pile, the underclass, really. I’ve noticed in America that “middle class” is used just about the average American, whereas in Britain in many ways it’s like the top third of society.

Your high-culture person who likes reality TV is always going to have a certain number of inverted commas around it when they watch it.

Guernica: How was that reflected in the UK general election in May?

Grayson Perry: I think it’s turkeys voting for Christmas. There must have been a lot of relatively poor people who were voting for the Tories. How they been conned into that, into thinking that they’re voting for someone who’s going to help them!

Guernica: How do you explain the subversion of taste expectations—for example, an otherwise highbrow person obsessed with reality TV. Is there an arbitrariness to the boundaries of taste?

Grayson Perry: I would say the boundaries are still really there, because your high-culture person who likes reality TV is always going to have a certain number of inverted commas around it when they watch it. There’s always going to be an element of ironic detachment in their enjoyment of it. I do it myself—you don’t just enjoy the program, which is often quite good fun and enjoyable, you’re also enjoying yourself enjoying it. It’s a meta-experience. There’s a brilliant TV program in Britain right now called Gogglebox. All it is—it sounds banal—is they choose a completely diverse group of people from across the country and they just film them watching the telly. They all watch the same program. They’ll cut between an Indian family up north, a posh couple in the south, a black family in Brixton, a gay couple in Brighton. They’ve chosen the families really well, and it is absolutely hilarious. And moving, sometimes, because they’ll have them all crying, and they’ll cut from one to the next and they’re all holding hands on the sofa and throwing funny comments to the telly. I always say to people if you want to see what Britain looks like, watch Gogglebox. It’s brilliant and funny and warm and clever.

Guernica: How much TV do you watch?

Grayson Perry: People are often horrified that I watch a lot of TV. But I say that’s my business! That’s where I get all my culture. TV now, especially the big American box set–type TV, is our literature, the high culture of our time. Things like The Wire and Game of Thrones—they’re the most crafted, well-funded, brilliantly devised things. And I think that people who turn their noses up at them are doing it at their cost. Telly is now heritage, because the Internet is now the devil. It used to be that telly was the devil, and now computer games are the devil, and the Internet. So telly’s been allowed to sort of sit there, and it’s got a gold frame around it now. We watch telly in a different way. I grew up with it so it’s like my heritage. My wife’s middle class, she could hardly watch television at all. I had to teach her how to do it. And now she’s more of an obsessive. I mean, she watches much trashier telly than I do.

Guernica: Given the importance of objects to taste, what objects do you have in your home?

Grayson Perry: I’m pretty lackadaisical because my business is supply, not consumption, on the whole. But like many an aspiring middle-class person, we’ve got way too many books. Because that is you showing your cultural capital, the physical form. Middle-class people always want to be filmed in front of a bookshelf. And our house is very messy, but that’s also a signifier, that you don’t care. It’s like the car thing: the posher you are the cheaper the car. If you have a very flashy car it’s very vulgar.

But there’s a bit of me that still takes pride in having something flashy. I quite like having a flashy motorcycle. And dressing up. I like to be unapologetic. If I got a car, I would have a really flashy car. Because of my position in the system, I feel like I can do that and get away with it. Whereas someone who’s insecure, they might want to be seen to do the right thing. I mean, people are absolutely in hock to it. My sister, she is tied up in knots trying to be a tasteful upper-middle-class person. And I think it cripples her life. She’d never design a house to be comfortable. A working-class person, if they had the money to buy a big house, they would buy a big house. They wouldn’t care necessarily what it looked like, it would have to work well, it would have lots of conveniences in it. A middle-class person would put the money into a house that has history, looks fantastic, but might be really inconvenient and have lots of little rooms and wiggly staircases where you bang your head on the beams or something. They would spend their money on the address and the look of the house, and the postcode.

Guernica: And the draft. The house has to be drafty.

Grayson Perry: Drafty, yeah, no double-glazing because that would be distasteful.

Guernica: How do you think digital technology is affecting taste? When Pandora or Netflix suggests what you should listen to or watch, are you essentially outsourcing your taste to algorithms?

Grayson Perry: Yeah, but they’re rubbish choices. They’re like the choices your aunty makes for you. It’s bollocks. It’s nerds. It’s people solving a problem that didn’t exist. I buy music on iTunes, and when Genius came along, I thought, OK, we’ll see what it comes up with. I never bought anything on Genius, it never makes a suggestion I want. Because it’s always following you, it’s never leading you. It’s seen what you’ve done before, and it’s making decisions on that. In the same way that the ads that come down the side of your browser, they’re about things you’ve already bought. I don’t need a bicycle, I was buying a bicycle last week!

Nothing is allowed in isolation to grow over years or decades and then pop out into the world consciousness as a pretty fully formed subculture.

Guernica: So you think people don’t actually pay attention to these things?

Grayson Perry: I think if people really want music they’ll search it out. iTunes used to have celebrity playlists. That one used to work for me. Because I’d find a celebrity whom I respected, and I’d look into their playlist, and that would lead me off in a direction. Often they would have interesting choices, and that would take me into places I wouldn’t normally know. And that was human contact, it wasn’t an algorithm.

A lot of people who work in computers think that the world is like them. And a big mistake that a lot of people in charge of culture make is they do autobiography as analysis. So they think, “It’s all like this!” And what you want to say to them is, “No, it’s like that for you. But I think you need to pan out a bit here and realize that we are all different.” And I think nerdy computer guys get off on gadgets and algorithms and all that, but human beings don’t.

Guernica: How is the web influencing culture?

Grayson Perry: The big difference about culture now with the web is that nothing germinates anymore. It’s force-fed. It’s like trying to grow culture really fast—the web is like a kind of hothouse. So somebody tweets something and it’s gone global and it’s already in mush. Nothing is allowed in isolation to grow over years or decades and then pop out into the world consciousness as a pretty fully formed subculture. I always use the example of mods in Britain. Mods started the jazz clubs in Britain in the late ’40s. They didn’t really come into the national consciousness probably until fifteen years later. By which point they had an underground style and a music and everything had all developed. Now, within a few days, somebody says, “Ah, there’s a hip club down in blah blah and let’s go down there and we’re going to start a club like that,” and then somebody in the Philippines will start a club like that and somebody in South America will start a club like that. It’ll all become, “Oh, yeah, we’re so fucking cool.” No, you’re not. You’ve just seen it on the web.

Guernica: You’ve described how good taste is about not alienating your peers. So do you have to forgo good taste to make good art?

Grayson Perry: If you want to be successful in the art world you’ve got to look to the art world; you don’t make it for the bloke next door and then hope the art world is going to look at it. That’s one of the big mistakes people make. Craft people, for instance, they’ll call themselves a potter or a craftsman or whatever, then they’ll hope that the art world is going to somehow recognize them as artists. It’s not going to happen. You’ve got to call yourself an artist and point yourself at the art world and make art for the art world. But of course the art world wants to be antagonized, that’s the great thing about it. If you can antagonize the art world, you’re made.

The art world is a slightly different place in that it’s so self-conscious and so sophisticated about issues of taste, but it still has the element of fitting in. I sometimes think when I make a lot of my artwork that it’s too colorful. It’s just not going to fit in with the design of the collectors’ houses, I better make a black-and-white artwork, or a beige-and-white artwork that will fit in to all the collectors’ houses better—more domestic friendly. I remember when I did the taste tapestries, I went around with [my gallerist] Victoria Miro and I’d not seen them hanging up before. We went around the gallery and they’re incredibly well lit and they’re kind of glowing off the wall with violent color. And I said, “Ooh, god, are they a bit much?” and she said something like, “Well, they’re not the most aesthetic.” [laughs] I thought, “You’re not meant to say that!”