Since 2005, a cataclysmic change has occurred in mapping. That period marked the beginning of crowdsourcing on Google Maps, a corporate giant whose name has now become almost synonymous with the word “map,” and, at the same time, the advent of OpenStreetMap, an open-source platform through which sheer volunteerism has made possible a so-called complete map of the world. Anybody with a smartphone or computer can now put a point on the map, meaning anybody can draw a map. This has shifted the power of mapmaking from experts to ordinary civilians, with all the attendant consequences and complexities.

Bill Rankin and I began our conversation on this subject, from which portions of the interview below have been adapted, at a conference in May for the New Museum’s Ideas City Festival. The theme of the event was “invisible cities,” but as I mentioned in my opening remarks, I think most things about cities are, in fact, visible. Streets, trees, grass, parks: all are visible. Oftentimes, when people say they’re exposing the “invisible city,” what they’re actually doing is putting data on a map, which can help you navigate a part of the city you might not normally go to. When the sociologist Saskia Sassen talks about invisibility in relation to slums and refugees and financial iniquity in her book Expulsions, what she’s really saying is that these are “invisible” because they are not visible in data.

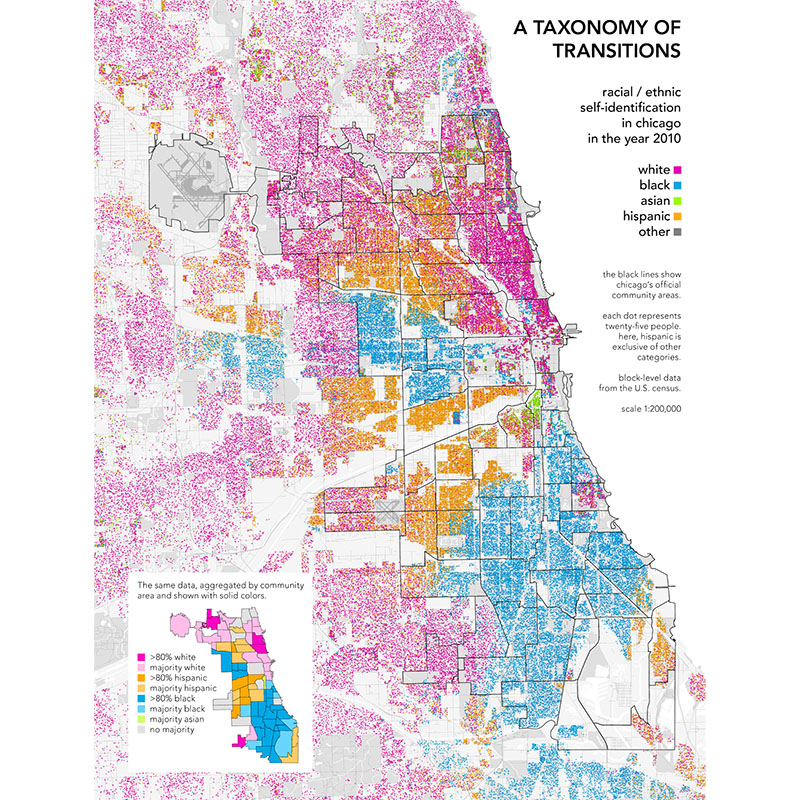

Bill teaches at Yale and has a dual PhD in the history of science and architecture, but he also makes the things he writes about, and actively theorizes about the things that he makes. He is the founder of radicalcartography.net, a website I visit often, that features hundreds of maps of everything from subways to global agriculture, exposing the limits and politics of projection methods, and other geographic information system (GIS) oddities. What I know him for, however, is a particular way of producing census maps that he advanced, particularly in the United States, which involves placing one dot on the map for every twenty-five people, instead of the more standard practice of showing people through averages or neighborhood majorities. This development has made population diversity visible on an unprecedented level, and has changed the way we look at race and segregation in cities across the United States, to name just one application. It has raised the bar for activist mapping, for accessible mapping, and for civilian-oriented mapping in general.

In my own practice, I am the director of the newly formed Center for Spatial Research—formerly the Spatial Information Design Lab—at Columbia University. Like Bill, I make things that I write about, mostly with spatial data, and theorize about what I make, often to expose the limits of data and maps. My book, Close Up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics, is a record of my early work with new mapping technologies—projects using GPS, remote sensing, and GIS technologies. I like to think of myself as one of the first artists who used GPS in a way that intentionally underscored its disorienting architectures and politics, and who has written about the pre-history of the use of the satellite imagery so naturalized on Google Earth, declassified only sixteen years ago. Nowadays, I act in collaborative teams across disciplines, on a range of topics from conflict urbanism to neuroscience, from critical cartography to critical data visualization. Like Bill, my work consists of making arguments with maps and data.

—Laura Kurgan for Guernica

Laura Kurgan: Today, in some sense, maps as we know them might as well be called data visualization, rather than cartography. What is your take on this distinction, in terms of your practice? We obviously both see value in making data visible in new ways, as maps.

Bill Rankin: This might be a case of a distinction without much difference. I think seeing mapping as a form of data visualization is really important, since it gets us away from the idea that maps simply mirror reality. Instead, a map is just one way of representing a given set of data—and data doesn’t just mean statistics, but also things like the location of coastlines and railroads. The same data can be represented in many different ways, and the finished map is more an argument about the world than a simple description. If there’s a case to be made for cartography as something distinct from visualization, it’s that spatial data, or geographic knowledge more broadly, raises a distinct set of political questions about spatial governance and identity.

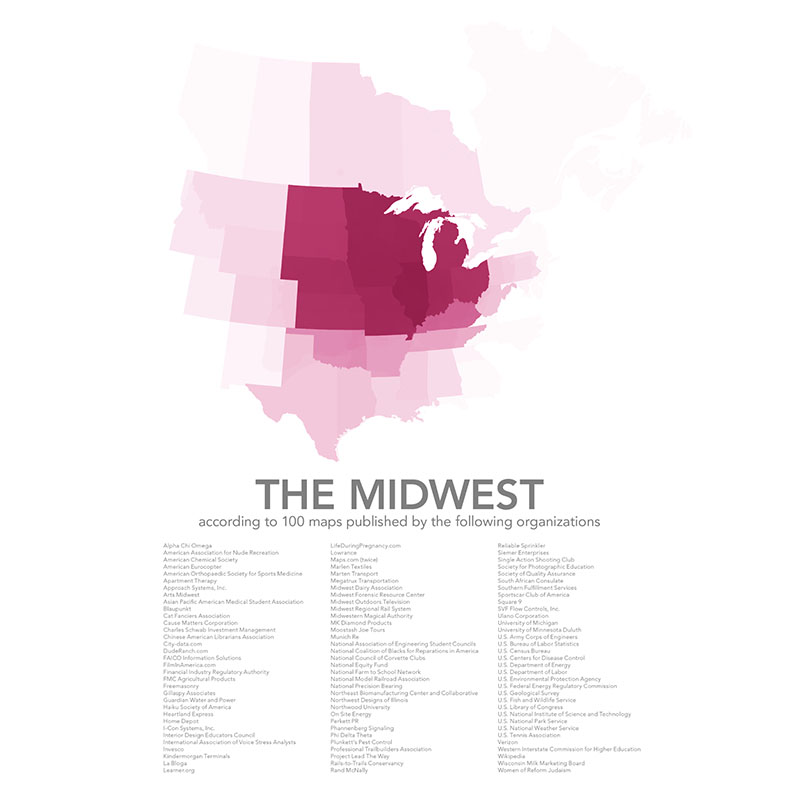

What I like about this map is that it makes it clear that the boundaries of the Midwest, culturally, are in fact quite fuzzy.

Laura Kurgan: Your website is called “radical cartography,” which obviously relates to the political questions you just mentioned. Can you elaborate on these politics and the ways in which you make arguments with maps?

Bill Rankin: For my own practice, I think this comes down to the word “radical,” because there are two different things that this word might mean when applied to cartography. One option is that radical could refer to the content of the maps. These maps would show things that are important for radical or activist politics—such as Trevor Paglen’s map of CIA aircraft movements or Eyal Weizman’s excellent mapping of the West Bank. I think this kind of mapping is really important and very useful, politically, but I actually think it takes a somewhat limited view of what “radical” might mean. What’s more interesting to me, and what I spend a lot of time thinking about, is that “radical” can instead refer to the way the map is made. It would be a radical process, rather than just radical content.

There’s a lot of interest today in bottom-up surveying and participatory data collection—and I hope we can talk more about this kind of mapping—but my own focus has been on rethinking the graphics of the map itself and the rules that are used to translate from raw data into finished cartography. For me, this mostly means using other people’s data in ways that they wouldn’t have used it themselves, in order to make new kinds of visual arguments. And again, the idea of visual argument is really crucial. It’s the way the map is drawn that makes the political intervention.

Take the example of census maps. The problem with most demographic maps is that, like a pastel-colored map of territorial states, they tend to assume that the relevant demographic boundaries fall exactly at the edges of official neighborhood areas and that all such edges are clean and well-defined. My alternative, which uses block-level data and hundreds of thousands of colored dots, isn’t just about showing more detailed data. It’s also about challenging implicit arguments about boundaries, homogeneity, and the so-called “inner city.” My map of Chicago, for example, which has now inspired many others, was certainly not the first map ever made of segregation. But it does show segregation in a new way. And I’ve been really pleased to see so many other dot maps being made now—everywhere from the New York Times to the Civil Rights Museum in Memphis. I get a lot of emails from people who say that they now see their cities in a different way. This is the power that cartography can have.

Another example is a more recent map I made of the American Midwest. And again I’m really interested in the question of boundaries and how to represent them cartographically. I started by collecting 100 different maps of the Midwest from the Internet; I then just overlaid them all together to see what kind of agreement, or disagreement, there was. What I like about this map is that it makes it clear that the boundaries of the Midwest, culturally, are in fact quite fuzzy. There’s a ton of disagreement. Obviously this isn’t as pressing of a social concern as segregation, but it’s still making an important argument about place, meaning, and collective imagination.

Overall I’d say that there are two ways I’m trying to radicalize cartography. The first is to place more emphasis on social landscapes, rather than the physical landscape alone. This means no longer seeing the road map or the aerial photo as the default. The second is to reimagine boundaries. Most of what we know about boundaries comes from maps, and by making new kinds of maps we can start to think about boundaries in new ways.

Racial/Ethnic segregation in Chicago. Map by Bill Rankin.

Laura Kurgan: You said you often take existing data sets and present them in a radically new way. I’d like to probe a little deeper into the census dot maps. Being somewhat of a GIS person myself, I know GIS professionals have all kinds of theories about how many dots the human eye can perceive, and worry that once too many dots pile one on top of each other, the dots lose meaning. Before interactive maps, dot maps were not that popular in GIS. Chloropleth maps, which assign one color associated with a legend across a political or geographic entity to represent a number range, were much more popular, and still are. There is something to this argument: at the wrong zoom level, piled up dots can’t be understood as a specific number of people. Today, faster computation allows faster rendering of data in real time on screens, and the zoom has radically altered web mapping platforms. While many who view maps online take the zoom for granted, nowadays many maps demand the zoom to a specific area and more data appears at that zoom. The zoom allows users to make sense of dot maps—for example, you can read a diversity of color at a specific scale.

Bill Rankin: Let me take the bigger question here, which is about GIS. There’s a long history of research that’s about trying to find hard-and-fast graphic rules for cartography. How do people perceive the sizes of circles on a map? Can the everyday map user distinguish six shades of gray, or seven? Do people make more reading errors when data is shown with squares instead of circles? This is not where I’m coming from. I’m coming from a design background, and now I’m a historian writing about the politics of geographic knowledge. So I’m not so invested in the psychometrics of map reading, because this often leads to maps that pass certain tests but that don’t pass the most important test, namely, does this actually tell us what we want to know?

A lot of the mapping that I’ve done is actually trying to push back against GIS, because the graphic language of GIS is coming from this long tradition of psychometrics and the idea that mapmaking can be reduced to a set of quasi-scientific rules. And I usually find myself wanting to do things that the software is really not intended to do—I want to experiment. So I use GIS opportunistically, and I’m often mashing it up with other software in order to get away from the idea that all maps should follow the same set of rules.

Laura Kurgan: Steve Romalewski, director of the Center for Urban Research at CUNY, put it to me in a conversation the other day, that “maps should eliminate, not obscure.” By this he means that a map should eliminate data that is unnecessary to an argument. So, for him, Brandon Martin-Anderson’s census map—which shows one dot per person—is fine computationally but demands a zoom, only a zoom, and hence, “does not allow population patterns to emerge from a larger-scale view.” What do you think about this debate, and about the directions others have taken with the dot census maps?

Bill Rankin: I’m not really worried about how many people there are per dot, and I agree that what really matters is understanding population patterns. I chose twenty-five people per dot because that made the most legible map at the scale that I was using, which showed Chicago on a nine-by-twelve-inch page. If I had been making a wall map, I definitely would have used fewer people per dot. I think it’s great to have these interactive dot maps where the number of dots per person changes automatically with the zoom level, as long as the map is still legible at every level. The politics here are not really about trying to give every person their own dot—although I certainly understand the symbolic appeal—but more about showing internal diversity within neighborhoods and within the large areas that demographers and urban planners are used to working with. How do you break into the pastel-colored shape and show the granular, multivariate data instead of averaging things out using a standard-issue choropleth map?

The contested boundaries of the Midwest. Map by Bill Rankin.

Laura Kurgan: I do think that one dot per person has a rhetorical weight, but we should move on. Let’s change gears a bit and talk about some other politics of current-day mapping. It’s clear that OpenStreetMap has really changed international disaster response, most recently in Nepal. At CSR we are working right now on a project to map damage in the city of Aleppo, in Syria, one of the most continuously inhabited cities in the world, over these last years of the war. On OpenStreetMap, Aleppo has some roads, it has some buildings, it has some landmarks, but much of the city has far less detail. Conversely, refugee camps, to which many Syrians have fled, particularly Zaatari, are mapped in copious detail, because the aid agencies are there. In some cases, what’s lacking on Google Maps but pronounced on OpenStreetMap is more indicative of the politics of these mapping resources than the politics of what’s happening on the ground. In mapping Nepal, after the recent earthquake, there seems to be a competition among a lot of mapping platforms that are built on top of OpenStreetMap to become the platform for disaster mapping, though they don’t, or perhaps can’t, share their data. What’s your take on demanding that data on open-source mapping platforms remain open?

Bill Rankin: I’ll start again with the broader question, which is about the politics of open-source data. First off, this is often framed as a debate that’s just about the corporate control of information, which I don’t think is quite right. There’s at least one other very important player, which is the government. There are a lot of countries—such as the UK or Canada—where mapping data is not made freely available to the public. Instead, they sell it, and it costs a lot of money. But in the US, the law says that anything created by the federal government is automatically in the public domain, and I think this is a great policy. Some of this government data is not so good, but a lot of it is very good, and it’s coming out of publicly funded scientific research—things like ice cap monitoring, land use changes around the world, remote-sensing data that can be used to document genocide, and so on. This is public data that can be used for the public good. This is the kind of data I’m most interested in. And this kind of data needs to be part of the conversation about open source. There are certain kinds of mapping that simply cannot be done in a bottom-up way—satellite mapping, for example.

The other thing that I would say is that there’s a politics here about who gets to decide what’s mapped. It’s hard to argue against making maps for disaster response or humanitarian aid. But it gets a bit more fuzzy in cases like informal settlements, where there’s some real debate about whether making those settlements visible to the state is actually beneficial or not—whether there’s a politics of remaining hidden that might be more strategic.

So even though there’s a lot to be said for crowdsourced mapping, it does foreclose certain political options, and it often bypasses important public debates about what kind of data should be collected and how it should be used. And these aren’t questions that can be answered in the abstract or from afar; they have to be rooted in specific political contexts.

Technology, like war, can often be a continuation of politics by other means.

Laura Kurgan: You’re hinting at a balance that needs to be struck between striving toward an impossible complete map of the world and the danger of trying to map things that should remain invisible, or unmapped.

Bill Rankin: I actually see great value in running a lot of these questions through a legal regime, where they are considered in public and in a way that is designed, at least in theory, to protect against brute-force majority rule. This process certainly has its flaws—it’s often inefficient and lags many years behind changes in technology—but in the US, the rights guaranteed by the Fourth and Fourteenth amendments are real and should be taken seriously. So I’m worried when a crowdsourcer or an NGO is the one to decide where the boundary is between visibility and privacy. And this should be doubly true when intervening in other countries or cultures.

For example, the next step in open-source mapping may be to collect information about individual households. This can certainly be done in a way that protects privacy, and I can imagine ways that an address-aware OpenStreetMap could contribute to the public good. But if the goal is to get around the privacy regulations that constrain the census, then I would worry about technology being used to subvert democracy. Technology, like war, can often be a continuation of politics by other means.

Laura Kurgan: I agree with you about the lack of regulatory structures around citizen mapping. But the debate by the mappers themselves often involves what should be done by the government and has not, versus what they can provide to their own neighborhoods and cities, for a start. Code for America is a good example—they develop apps that allow volunteers to step up when government systems are lacking. A lot of what they enable are mapping projects. What if they do a better job than the government, and for less money?

Bill Rankin: Again, there are certain kinds of data that can only be produced by governments or huge organizations, and I think there’s real value in this kind of data. There’s also a lot to be said for the kind of data that’s been collected by OpenStreetMap, absolutely. And then there are areas where the lines get fuzzy. Even if citizen mapping ends up being cheaper than government mapping, how would we make sure that all neighborhoods are given the same attention? Where is the line between holding government accountable and replacing government altogether? Just because there are debates about efficiency doesn’t mean that we only have two choices—all government or all crowdsourced.

Privacy and security are major issues here, too. Google Street View has already raised privacy issues, especially in Europe, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Google or Facebook or some other company with a huge amount of personal data started experimenting with new kinds of mapping to rival the census. Right now there are also regulations about the allowable resolution for aerial photography, mostly coming from the military. I can imagine these being challenged or circumvented by new kinds of drone mapping. These are the border cases where it’s important to talk about what kinds of mapping should be done, and by whom, and how that data is then made available.

But I do think that whatever public data does end up being collected should be freely accessible, and volunteer organizations and NGOs don’t always share their data. In my own work I’m often frustrated when all I can find is a finished map, because that finished map has already been put through a certain set of goggles—a certain lens that is showing me one version of that data. I want to be able to look at the data myself and see what else I can learn. And maybe I’ll find that the data is really problematic and shouldn’t be used at all.

Laura Kurgan: An audience member at our Ideas City panel raised the issue of mapping indigenous land and working with indigenous populations to make maps. As you said in your response, this can involve “encountering cultures that have no mapping tradition that we recognize at all. Their geographic knowledge—often very sophisticated knowledge—is not map knowledge.” You asked: “What do we do? Do we try to translate that knowledge into a mode that we understand? Do we invite other peoples to make maps even if they don’t see the value?” Can you expand a little on this issue?

Bill Rankin: This is really the same issue that we’ve been talking about, just in a broader perspective. In the 1990s, when anthropologists first started writing about “counter-mapping”—where NGOs help indigenous groups make their land claims legible within a Euro-American system of land ownership—there was a real discussion about the pros and cons of freezing and rigidly spatializing these systems of land use that were quite fluid and social. But now, twenty years later, I see very little debate. The assumption is usually that making maps and collecting spatial data for GIS is always the right answer and will inevitably lead to increased political representation and a better distribution of resources. But I’m not so sure. At the very least, there can’t be a one-size-fits-all solution—different situations call for different strategies. And we need to ask whether the goal is to help people—which often has unintended consequences—or to empower people to be part of a political process. The former is about making decisions for others; the latter requires relinquishing control in ways that aren’t always easy.

Completeness is as much about what’s been ignored as it is about what’s been mapped.

Laura Kurgan: Let’s finish by going back to the question about the so-called completion of the map of the world. What do you think about the news that OpenStreetMap has essentially finished its task, and now the issue will just be keeping it up to date?

Bill Rankin: The question of completeness is always a question about what we want to map. The criteria for OpenStreetMap, for example, is that the map should include anything that’s visible. But of course there are lots of things that are not visible that we still care about: things like the value of a farm, demographic changes over time, or even just temperature, rainfall, and average cloud cover. Completeness is as much about what’s been ignored as it is about what’s been mapped. It’s also worth noting that the line between visible and invisible isn’t always clear. Are street addresses visible? What about political boundaries?

Our starting point has to be that replicating the entire world is simply not an option. Sure, it might be possible to catalogue all the physical stuff; this is the traditional cartographic project. (Although it’s worth remembering that this is scale dependent. No one is proposing to map the location of every individual tree or every pile of gravel.) But there’s always going to be a discussion about what else we care about. And this isn’t just about the sheer difficulty of mapping everything; there are also phenomena just now coming into being that have never existed before. Climate change is one obvious recent example. There’s always going to be a question about what should be represented and how the data should be captured.

The other thing I would add, more on the side of cartography than data collection, is that working on new kinds of graphics and representation is also a powerful argument against completeness, even if the data doesn’t change at all. We especially have to be careful not to think that the options available in the current software are the only options that exist. For example, in one of my courses I assign Jacques Bertin’s Semiology of Graphics, an important and ambitious book from the 1960s. Bertin spends a lot of time exploring all the ways that the same dataset can be represented with dozens of different graphic techniques, and it’s amazing how few of them are possible with GIS today. So I think it’s really important to spend time with these kinds of sources—or just with pen and paper—and to think collectively about what kinds of maps we want to make. And then we should find the tools, and the data, to make them.