In September 2001, a few days after the World Trade Center attacks, the novelist Don DeLillo walked to Ground Zero. Civilians weren’t being allowed in lower Manhattan without proof of residency; DeLillo slipped past the barricades with his editor, who lived downtown. “It was a gray landscape, virtually empty,” DeLillo recalls. “A few people wandering around. Stacks of garbage bags on the sidewalk, uncollected. An elderly man trying to talk a policeman into letting him back into the shop he owned. I had a sense of an old city—an old, partly ruined city in another culture, somewhere under siege. The few people I encountered, most of them were on cell phones, describing the scene.”

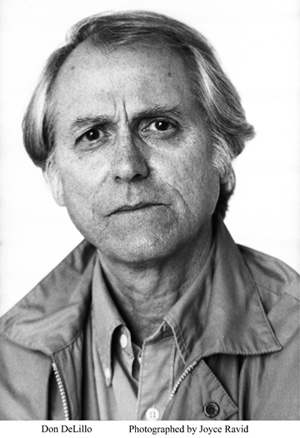

DeLillo originally traveled to Ground Zero with vague intentions of writing an essay about the attacks. (The essay was eventually published in Harper’s in December 2001.) “But I was thinking as a novelist,” he says. “I needed to see things, to literally smell things. I wanted to start at street level.” DeLillo is 70, with a slight build and glasses that look outsized on his thin face. His default expression, at least when he’s being interviewed, tends to the severe, that of a priest from some obscure ascetic order. This morning, sitting in a library at his publisher’s office in midtown Manhattan, he’s wearing a grey V-neck sweater over a green collared shirt. He speaks in a gentle, slightly high-pitched Bronx accent that always seems on the verge of collapsing into a lisp.

With his fourteenth novel, Falling Man,published in May, DeLillo has turned his attention to the events of September 11th and its aftermath. The book opens with an investment banker, covered in ash and holding a briefcase, walking from the burning towers. The man doesn’t stop until he reaches the apartment of his wife, from whom he has been separated, and young son. The rest of the book traces the effect of the attacks on the family’s fragile reconciliation, with various interludes touching upon a Las Vegas competitive poker tournament (DeLillo once played in a weekly game), a leftist German art dealer with a shadowy past and the indoctrination of one of the Saudi hijackers. There are also haunting appearances by a performance artist called the Falling Man, who throws himself from New York landmarks in a pose mimicking the famous photograph of a man plunging from one of the towers.

As many critics have noted, the fact that DeLillo would attempt a “9/11 novel” is hardly surprising. He’s been writing 9/11 novels for the past thirty years. Terrorists have been making regular appearances in his books since Players(1977) a satirical portrait of a young urban professional couple. (The husband becomes involved with a terrorist group that is plotting to blow up the New York Stock Exchange, where he works; the wife, meanwhile, is employed by a firm called the Grief Management Council, which is based in the World Trade Center. At one point, during a rooftop dinner party in which the wife gazes at the towers, a neighbor casually notes, “That plane looks like it’s going to hit.”) Other favorite DeLillo themes—conspiracy theories, cult violence, religious fanaticism, large-scale cataclysmic events, the terror of crowds, secret histories, lone men in small rooms plotting dramatic acts of violence—all but make Falling Man seem inevitable. The word “paranoid,” seemingly required in early reviews of DeLillo’s work, has since been replaced with “prophetic.” (He owns up to neither: “What I try to do is understand the currents flowing through the culture around us. That’s where all the paranoia comes from in my early novels.”)

DeLillo grew up in a working-class Italian neighborhood in the Bronx. His parents were immigrants from Abruzzi. His mother worked as a seamstress and his father, described by DeLillo as “a blue collar man who ended up wearing a suit,” worked as a payroll clerk for Metropolitan Life. DeLillo played sports as a kid, and was not especially bookish. (Sports figure prominently in several of his books, including his second novel, End Zone,about nuclear war and a college football team, and Underworld,

which opens, famously, with a panoramic scene at the 1951 World Series. DeLillo also published a novel called Amazons, about a female hockey team, under a pseudonym in 1980, but has never publicly acknowledged the book and refuses to allow it to be reprinted. First editions can now fetch up to $400 on eBay.) It wasn’t until DeLillo worked a summer job as a parking attendant, when he was eighteen, that he began using his downtime to pursue serious reading. “We were called parkies,” he recalls. “I wasn’t wearing the standard outfit that such people were supposed to wear, and I just sat, disguised, on a bench in the playground, reading Faulkner and Henry James and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Not knowing that I would become a writer, certainly. Not knowing that at all for several years. But I suppose I was beginning to sense the power of serious literature.”

After attending Fordham University, he began working as a copywriter at a Manhattan advertising agency. “Print ads, very undistinguished accounts,” he says. “I hadn’t made the leap to television. I was just getting good at it when I left, and maybe that was a secret reason for me to leave.” DeLillo’s friends assumed he’d quit his job to write. “Actually,” he says, “I quit my job so I could go to the movies on weekday afternoons.”

[Interview by Mark Binelli]

Guernica: It would seem like writing about September 11th would be incredibly daunting. You’ve written about similar events in other novels, like the toxic cloud that passes over the city in White Noise, but there’s generally a certain amount of irony and distance.

Don DeLillo: It is daunting, extremely. And the fact that I decided to go directly into the middle of the event didn’t make it any easier. I didn’t want to write a novel in which the attacks occur over the character’s right shoulder and affect a few lives in a distant sort of way. I wanted to be in the towers and in the planes. I never thought of the attacks in terms of fiction at all, for at least three years. I was working on Cosmopolis on September 11th, and I just stopped dead for some time, and decided to work on the essay instead. Later, after I finished Cosmopolis, I had been thinking about another novel for some months when I began thinking about what would become Falling Man. What made it happen was a visual image: a man in a suit and tie, carrying a briefcase, walking through a storm of smoke and ash. I had nothing beyond that. And then a few days later, it occurred to me that the briefcase was not his. And that seemed to start a chain of thought that led to the actual setting of words on paper.

Guernica: Did this image just come out of nowhere, or from a photograph, or from stories of people you knew?

Don DeLillo: It just came out of nowhere, as these images tend to. It frequently happens that I begin a novel with just a visual image of something, a vague sense of people in three dimensional space.

Guernica: Which of your other novels started that way?

Don DeLillo: Well, certainly The Body Artist. I imagined people at breakfast, people who know each other intimately, probably a husband and a wife, speaking in unfinished sentences, in grunts, in coughs, as people do, particularly at that time of day. And I wondered what it would be like to sit down at that kind of dialogue, in which sentences are rarely completed and thoughts are rarely followed up and one person is not really listening closely to another. That’s all I had. And that’s when I began writing.

Ultimately it’s not religion, it’s not politics and it’s not history. It’s a kind of blood bond with other men. And the intensity of a plot, which narrows the worlds enormously.

Guernica: One of the characters in Falling Man, Hammad, is one of the 9/11 hijackers. Did you ever consider writing the entire book from his perspective? You’ve written so much about terrorism in the past.

Don DeLillo: I did not want to write a novel that had a great deal of political sweep. With the terrorist, I wanted to trace the evolution of one individual’s passage from an uninvolved life to one that becomes deeply committed to a grave act of terror. And that’s what I did. Not that I planned this beforehand. I mean, what I do, almost always, is I just start writing and through a character arrive at a sense of an overarching scheme, perhaps, under which he moves. With Hammad, I wanted to try to imagine how a man might begin as a secular individual and then discover religion, always through the power of deep companionship with other men. This is the force that drives him. Ultimately it’s not religion, it’s not politics and it’s not history. It’s a kind of blood bond with other men. And the intensity of a plot, which narrows the worlds enormously and makes it possible for men to operate without a sense of the innocent victims they plan to destroy.

Guernica: You often write about that sort of self-imposed asceticism. In Falling Man, there’s a great scene in which some men involved in a weekly poker game begin to impose absurd limitations on what they can and cannot do, which ends up mirroring some of the rules imposed on the hijackers by their leaders.

Don DeLillo: That’s true. Although I wrote the poker scene largely because I thought it was funny. I’m not sure I have a clear explanation for the asceticism of my characters in general. There are examples in a number of novels, including Great Jones Street, where a rock star abandons his career and lives in an obscure room somewhere in lower Manhattan. Maybe I have an ascetic gene that I haven’t given full recognition to, except in my fiction.

Guernica: You don’t personally yearn for those sorts of limits?

Don DeLillo: Only in a very general sense, in that I’m not very gregarious and don’t mind spending periods of time alone.

Guernica: In a number of your past books, your characters have also expressed ambivalent feelings about the idea of terrorism. In the opening of Players, you describe the “glamour of revolutionary violence, the secret longing it evokes in the most docile soul…” And in Mao II one of the characters says of terrorists, “It’s difficult when they kill and maim because you see them honestly now as the only possible heroes for our time… the way they live in the shadows, live willingly with death.” Did what happened on September 11th change your own thoughts about terrorism?

Don DeLillo: No. I tend to write through character consciousness, and different people in my books have different feelings about this matter. One of the characters in Falling Man, Martin, makes a greater attempt to understand the complaints against the narcissistic heart of the West. The character he argues with, Nina, does not disagree with this in theory, but when the attacks occur, something else occurs, which is a terrible outrage.

Guernica: Did you struggle with similar responses yourself, after the attacks?

Don DeLillo: No, I didn’t struggle. I knew I was totally opposed to what happened and to the reason for it.

Guernica: What were your feelings about some of the more extreme radical groups in the Sixties, like the Weather Underground? Someone in Falling Man, referring to a character who may have a violent radical past, says, “Maybe he was a terrorist, but he was one of ours—godless, Western, white.”

Don DeLillo: Groups like the Weather Underground were not outsiders. They were not the Other, as the Islamic terrorists are seen by those of us in the West. That has seemed to make it easier for such men and women to reenter society, and continue to be admired. I don’t think that would be the case with terrorists of other skin colors or other languages.

I marched and I protested against the war in Vietnam, along with many, many thousands of others. But I never quite understood the bombs that were placed in science labs or office buildings.

Guernica: I think one of the former Weathermen won a bunch of money on Jeopardy.

Don DeLillo: Is that right? I wasn’t aware of that. Well there you are. And of course there have been documentary films about American terrorists, and in most cases I know of, they carry a certain amount of respect and admiration.

Guernica: What were your feelings about those sorts of violent radical acts at the time?

Don DeLillo: With that kind of radicalism, on the one hand, one understood the roots of it. On the other hand, much of it seemed mindless and obscured by elements of the lifestyle of that era. You know, I marched and I protested against the war in Vietnam, along with many, many thousands of others. But I never quite understood the bombs that were placed in science labs or office buildings.

Guernica: What kind of affinity did you feel, if any, towards the Sixties counterculture?

Don DeLillo: Well, I was never either pro-culture or counter-culture. I was in a kind of middle state. It’s a little hard to describe, actually. I lived in a very minimal kind of way. My telephone would be $4.30 every month. I was paying a rent of sixty dollars a month. And I was becoming a writer. So in one sense, I was ignoring the movements of the time. My first novel is not deeply involved with any of that.

Guernica: Was this sort of minimalist living part of just being focused, or was it more a factor of you being a poor, struggling writer?

Don DeLillo: More the second than the first. But the fact that a character in my second novel ends up in the West Texas wilderness and a character in my third novel becomes a recluse in a room somewhere is a further indication of my state of mind at the time.

Guernica: People have speculated that Bucky, the rock star in Great Jones Street, is based on Bob Dylan, who had his own reclusive period.

Don DeLillo: No, no. I mean, people always say that about characters in everybody’s novels. But I’m not aware that Dylan and Bucky have anything in common.

Guernica: Was it fun writing song lyrics for that book?

Don DeLillo: It was. But that’s one of the books I wish I’d done differently. It should be tighter, and probably a little funnier. And there’s a literary element I wish I didn’t explore concerning, if I remember correctly, a drug that is literally silencing people.

Guernica: Have you ever tried to write songs outside of fiction?

Don DeLillo: Never. I am very unmusical. I can’t carry a tune. I would never be able to play an instrument.

Guernica: Do you listen to music when you write?

Don DeLillo: No. I listen to music when I am exercising—jazz, occasionally rock, occasionally qawwali [Pakistani devotional] music. But mostly jazz. The music I like best is kind of frozen in my mind from the Sixties and Seventies. I still listen to the same jazz music I listened to when I was eighteen years old, and like and admire it just as much: Coltrane and Monk and Miles Davis. This was the great discovery I made when I was young, and I am still discovering it. And in rock, it’s all those people that made the rock revolution. I used to go to the Fillmore East and see Jefferson Airplane and Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa and Joni Mitchell. Sha Na Na.

I knew I wasn’t writing hits.

Guernica: Who would you say were your biggest literary influences?

Don DeLillo: Well, you know, people don’t seem to link my name with Norman Mailer, but in a number of ways, Mailer was a strong force, because he was at the center of the culture and I was at the opposite end, so to speak. And I admired his writing and his opinions and the fact that he was a writer who was highly visible. Again, largely because that is the last thing I would want to be myself. And so I remember living in one room for years, and one of the books I kept picking up was Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself. That was nonfiction of all sorts, and I just found it endlessly interesting. Before that, there were Joyce and Faulkner and Hemingway and Flannery O’Connor and a few other writers.

Guernica: What about Pynchon?

Don DeLillo: I’ve always respected him. He put American fiction on another path, which was worth following.

Guernica: In what way?

Don DeLillo: Well, I think I’ve said this before, but it was as though Hemingway died one day and Pynchon was born the next. And fiction changed in that manner, abruptly, from pure realism to something more cosmic.

Guernica: Have you met him?

Don DeLillo: I’d rather skip that.

Guernica: I was hoping you’d say he was part of your weekly poker game.

Don DeLillo: He wasn’t.

Guernica: Do you have any favorite genre writers or books?

Don DeLillo: I don’t really read much of that. I don’t read detective work and I am afraid I don’t read graphic novels.

Guernica: That’s interesting, because your books often make little feints in that direction. I’m thinking about, for instance, the shooting at the end of White Noise.

Don DeLillo: That was intentional. If I can recall my design accurately, it was to reduce the idea of death to a tabloid level. Running Dog, I think, would also meet your definition. I wrote that book in four months. I hope it doesn’t look it. Maybe it does.

Guernica: Were you thinking of Running Dog as a sort of refraction of genre material or as an actual attempt at—

Don DeLillo: I knew I wasn’t doing utterly serious work, let me put it that way.

Guernica: But did you think it might be a hit?

Don DeLillo: I knew I wasn’t writing hits.

Guernica: Going back to Falling Man, I was thinking about how Bin Laden’s name is misheard as “Bill Lawton” by the kids, which makes him sound very mundane, and also how certain characters keep seeing the World Trade Center towers in a still life of bottles and other kitchen objects. Was this a conscious decision, taking an event that was so overwhelming to so many people and yoking it to the more mundane?

Don DeLillo: Absolutely. I was thinking about the impact of history on the smallest details of ordinary life, and I wanted to see if I could trace an individual’s interior life, day-by-day and thought-by-thought. It occurs to me that this could be the novelist’s initiative, even more than the story—to find the smallest intimate moments that people experience and share in conversation. I had none of this in mind. I just wanted to get the characters clear and, over time, create a balance, rhythm, repetition. This is what became satisfying to me. I was writing out of sequence and then began to fit the parts together and, as I say, look for these balances and the way in which the past yields the presence and vice versa. Sometimes this is what I think novelists do that makes them similar to painters. Abstract painters in particular. Looking for things in one part of a canvas that echo things in another part of a canvas.

Guernica: There was an essay in the New York Times a couple of years ago by the writer Benjamin Kunkel about terrorists and novels, and he used you as a primary example. Here’s another quote from Mao II: “What terrorists gain, novelists lose. The degree to which they influence mass consciousness is the extent of our [the writers’] decline as shapers of sensibility and thought. The danger they represent equals our own failure to be dangerous.” It seemed to me like Kunkel took your idea and basically extrapolated from that, arguing that writers really do believe what your character said, that writers feel less relevant in the age of terrorism.

Don DeLillo: I don’t know about that. The person in the novel who makes this statement isn’t even the novelist. He’s a publicity director for a terrorist group. I don’t know if I would make it that clear myself. But I do think, when I wrote that book [published in 1991], because of terrorism and dictatorship and turmoil in various countries, I perceived a new level of significance for the simple news of the day, on radio, on television, in the newspapers and in the magazines. The news seemed to have more force than it had in previous years. Now does that really affect the influence of novels in our time? That’s a very shaky premise. There may be some connection. But I wouldn’t want to make too much of it myself.

Guernica: And what about the notion that novelists want to be dangerous?

Don DeLillo: I’ve always felt that my subject was living in dangerous times.

Mark Binelli, the author of Sacco and Vanzetti Must Die!, is a contributing editor at Rolling Stone. His first article for Guernica, in May 2006, profiled the Daily Kos’s Markos Moulitsas Zúniga.