When she was twenty-six years old, Jill Freedman saw policemen knocking down Vietnam War protesters in New York City. Passionately anti-war, she asked a friend for a camera and began photographing their confrontations. She had never used a camera before, but everything clicked into place. “I knew that I had found my thing,” she said. “It’s like music, the rhythm of it. Photography was just natural to me.”

A Pittsburgh native, Freedman grew up in the heavily Jewish Squirrel Hill neighborhood. She still has fond memories of Mrs. Weinstein’s Deli, famous for its latkes and blintzes. She majored in sociology at the University of Pittsburgh, but spent her junior and senior years singing in a jazz group that played in steelworker bars. “You could do what you wanted,” she said. “Nobody was listening.” After graduation, she headed to Israel by ocean liner, spending 1961 and ‘62 in an apartment above the famous Bezalel Art School and singing in local clubs. These were modest performances, she said, adding that she “played the seven chords that I knew on the guitar.”

Freedman was deeply affected by accounts of the Holocaust. Although her parents did not want to talk about it, she found old issues of Life Magazine in the attic with photo essays on the subject. It was in these magazines that Freedman discovered the work of W. Eugene Smith, whose images focused on regular people who lived regular lives.

After two years in London, Freedman settled in New York City where she landed a job as a copy writer at the prestigious advertising firm of Doyle, Dane, and Birnbach. The pay was good and the office was fun. But everything changed on April 4, 1968, when she learned that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated.

“I was very upset about King’s death,” she said. “I saw a guy in overalls, a recruiter, standing in Central Park. He was trying to get people to join the Poor People’s Campaign. I was angry. Why, I kept asking myself, do the good people always seem to get it.” So she joined the Campaign. “Whatever was going on, I was not going to miss it.”

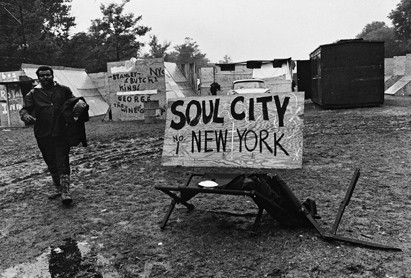

Thus began Freedman’s journey on the Greyhound bus caravan to Resurrection City, the name of an encampment on the National Mall that was at the center of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s attempt to tackle economic and social injustice.

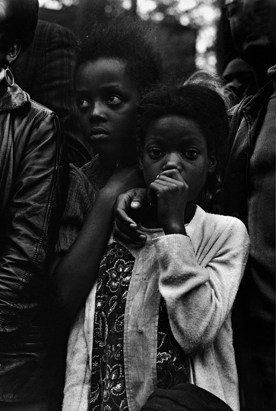

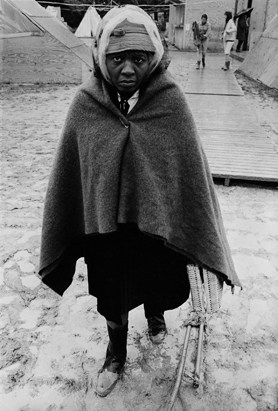

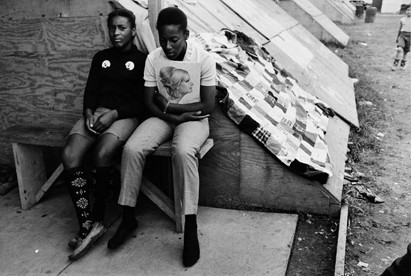

Freedman was one of several thousand people—blacks, whites, Puerto Ricans, and Native Americans—from nearly all fifty states who settled in the wooden and canvas shanties they planted in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial. Over the camp’s six week lifespan from May 13th to June 24th, 1968, Freedman tramped around in the muck, fought off mosquitoes, and photographed occupants’ daily lives. “This was the first story that I ever shot or wrote,” she said. “I wanted to get everything and people welcomed me because I, too, was living in the mud.”

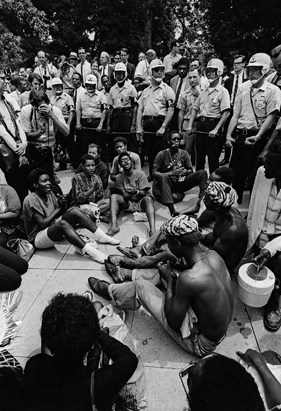

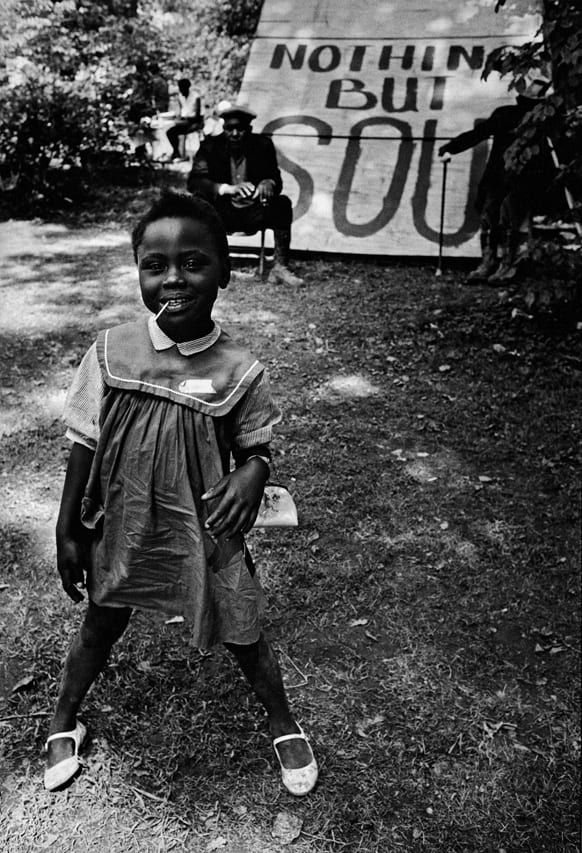

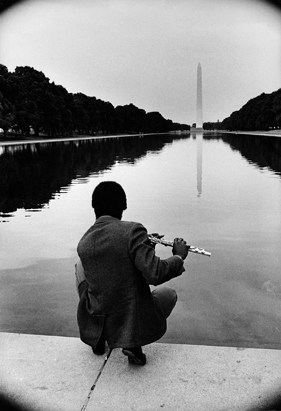

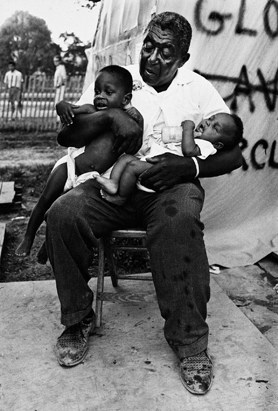

Freedman certainly did shoot everything: A proud African American woman, her hands clasping her umbrella, barefoot on the steps of the Capitol; a grandfather holding his two grandchildren in diapers; a girl smiling at the camera, standing in front of a shanty with the words “NOTHING BUT SOUL” printed in large letters; a woman watching TV inside a shanty; an old woman in mud-covered boots taking a rest inside a shack; kids playing on a tire swing next to a shack; protestors clapping and chanting next to baton-carrying police on the day the Civil Disturbance Squad shut down the encampment; a demonstrator playing the flute by the Reflecting Pool. We see a young Freedman, too, her Nikon around her neck, arms crossed, and standing next to John Mosely, a demonstrator who brought his wife and large family to live in Resurrection City.

A foreword that Freedman wrote in 1970 for Old News: Resurrection City, 1968, still rings true in the recently published 2017 book, released to accompany the first exhibit of these photographs, Jill Freedman: Resurrection City, 1968, on view at the Steven Kasher Gallery until December 22nd.

Of course, it was old stuff from the start. Another nonviolent demonstration. Another march on Washington. Another army camping, calling on a government that acts like the telephone company. Even poverty is ancient history. Always have been poor people, still are, always will be. Because governments are run by ambitious men of no imagination. Whose priorities are so twisted that they burn food while people starve. And we let them. So that history doesn’t change much but the names. Nothing protects the innocent. And no news is new.

“Those words are so true today,” Freedman said, launching into an anti-Trump tirade. “There’s no such thing as progress. If anything, in civil rights we evolve, we devolve. Trump is very dangerous. He has no idea what nuclear is. He will get us all incinerated.” Freedman would never vote Republican, but she is mad at the Democrats, too, “because of what the DNC did to Bernie Sanders,” her chosen candidate.

Things were different in 1968. “We believed that the PPC would make a difference,” she said. “The people in Resurrection City were some of the best folks I ever met in my life. Black, White, Hispanic, Indian. Look at my pictures. This was about being human.”

Gallery director Steven Kasher describes Freedman’s photos as a kind of family album. As an expert on the Civil Rights movement himself (he has curated nearly forty shows on Civil Rights and the counter culture of 1960s over the past twenty-five years), Kasher has seen all of the archive. “Jill’s images stand out because she was embedded with the protest,” he said. “Jill is the kind of person who bonds immediately. She’s incendiary. She has a kind of fiery response and identification with people.”

Kasher dubs Freedman a latter-day Weegee. Why? “Because Weegee was radical. He treated everyone equally in a radical way. If you were a bum on the street or the governor of New York, you got the same treatment: skeptical, satirical, with a comedic sense. Freedman is like that, too. It’s her character. Everyone is treated with the same humor, sensitivity, admiration and empathetic response. Except some of the cops in Resurrection City, who were the bad guys.”

Complementing Freedman’s bold photographs is her lean, poetic text. Not an extra word. She said that she does not like to write, and confessed that she often “writhed on the floor” struggling to get the right word. She despises purple prose and admits that “every time she gets rid of an adjective or adverb,” she is happy.

If you forget about things like traffic lights and dress shops and cops, Resurrection City was pretty much just another city. Crowded. Hungry. Dirty. Gossipy. Beautiful. It was the world, squeezed between flimsy snow fences and stinking humanity. There were people there who’d give you the shirt off their backs, and others who’d kill you for yours. And every type of in between. Just a city.

Her words are unflinching. Freedman digs deep into the human psyche, acknowledging the good, the bad, and the in-between: a line of cops, nightsticks in position facing a row of demonstrators, who are holding hands; a striking shot of a policeman’s back, his fingers curled around his nightstick, as he confronts a group of demonstrators, their heads held high, their faces resolute, some even with defiant smiles. Good and evil, right and wrong, with life in the mud nearby continuing as ever—people dancing, and children playing.

Freedman’s description of her final night in Resurrection City, June 23, 1968, when the cops moved in and tear-gassed the demonstrators, is haunting. She was babysitting Cato, the seven-year-old son of a friend, when someone saw the cops. “Weird plastic faces, yards away,” Freedman writes, “filing stealthily along the fence. Hundreds of them. Thousands. Why? What do they want? At this hour? So many of them? What are those big guns? And a flash of fear runs, silent as cops, up my spine and over my scalp.”

Freedman describes how Cato insists upon finding his kitten before fleeing. She comforts the child by telling him that “they’re not shooting bullets, just gas,” and that the cops “don’t want to hurt us. They just want to scare us.” As they run from the gas, not sure of which direction to go in, her eyes begin to sting and her throat to feel sandy. “We are trapped like rats, the bombs bursting in air, we wait our turn, this being a democracy,” she writes.

The night ends with Cato referring to the cops as “The dirty bastids.” The demonstrators, as Freedman describes them, were “a rag-tag crowd that didn’t have time to dress for the party… People testifying. People clapping. Black Powa, Black Powa. Freedom now. All together: Now.”

Powerful, poignant, poetic.

I understand that they had to attack the people of Resurrection City, because they were afraid. Afraid of the strength that has withstood the endless rain; the stinking mud, the mosquitoes; the cold, the wet; the bad food; the respiratory epidemic, born of the elements nursed by the gas.” Although the cops have “shot enough to knock out half of Washington, DC, and a little bit of Virginia, too,” ultimately, they have failed. “How do you gas a song?” Freedman asks. “You can, unfortunately, kill a man, but how do you kill his dreams. When the dreamers hoarse and red-eyed, righteous and inevitable, sing louder than before. And breathing this music, overcome by love, I get a funny feeling that this is the last time. The last time for something we have known and grown comfortable with. But only the start of something we have yet to feel, much less understand.

Most press accounts of Resurrection City, then and now, describe it as a failure, a protest that had little effect on changing federal economic and social policy. But Jill Freedman’s photographs remain as a tribute to its historical importance, an intimate documentary of life on the National Mall in 1968.

Freedman and Kasher are currently working on a future project that Freedman calls Madhattan, editing largely unpublished photos of parties, events, and street scenes from 1970s and 1980s. So far, they have come up with over three hundred images. Recently, despite her conviction that social media is largely garbage and chatter, Freedman has begun to embrace the Internet, putting up pictures on Instagram and Facebook.

Kasher admits that Freedman’s work is often scruffy and dirty and maybe “too wacky and wild for the world,” but he is convinced of its quality. “She should be in a museum,” he said.

Jill Freedman: Resurrection City, 1968 is on view at Steven Kasher Gallery, 515 West 26th St, New York, NY, through December 22