Collection of Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Gift of Lannan Foundation

On a steamy May morning south of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Erica Bowers Welch, a 46-year-old mother of eight and grandmother of three, debated the Book of Jeremiah in her Old Testament college class at the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women (LCIW). She listened intently as her professor reviewed information for their final exam, which would take place the following week. With her sharp cheekbones, accentuated by hair piled high on her head, Erica exuded a flair that defied the drabness of her prison-issued blue shirt. She sat with her twenty-three classmates at battered tables in the chapel classroom. A map of Jerusalem in the time of Jesus was the only thing disrupting the cinderblock monotony of the walls.

Jeremiah, explained Dr. Kristi Miller, is a book about being oppressed by a foreign power (the Babylonians) but also about how faith in God freed the Israelites. “God does not play with those who oppress others for their own gain. It is a message against people in power. God takes seriously those who abuse their position of power,” she explained. The lesson seemed unusually apt for a maximum-security prison setting.

As Erica and others listened, Dr. Miller drilled them with potential exam questions. “How long were they in captivity in Chapter 25?” The class answered automatically: “Seventy years.” There were a lot of murmurs and sighs. Erica is over a decade into a forty-seven-year sentence, and most of the other women are lifers without even the possibility of parole. Most of them will die here. When Erica finishes her bachelor’s degree in Christian ministry next year as part of the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary’s (NOBTS) first graduating class, she won’t return to the free world. She and her classmates will be sent forth to spread the word of God and, the seminary hopes, reduce violence throughout the vast Southern prison archipelago.

The prison seminary is part of an experiment sweeping through some of the most notorious prisons in the South. In Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida, and elsewhere, Baptists and prison administrators are molding an army of prisoner missionaries. In the past, these prisons were the epicenter for punitive incarceration. Most of them are former slave plantations or convict-leasing farms where bodies were measured solely in profit and loss. Now these prisons are at the vanguard of a movement where belief in the necessity of punishment coexists with the hope for an individual prisoner’s redemption. The seminary’s idea of freedom for a prisoner is for them to find Jesus and convert others without ever leaving prison.

When the NOBTS program opened at the women’s prison in 2011, Dr. Miller and the warden asked Erica to apply based on her incident-free record and high scores on the academic test administered to new prisoners. Initially one of a pool of a hundred applicants, Erica was admitted into the class of twenty. When I asked Erica about her favorite aspect of college, she replied, “Breaks.” But Erica is grateful to be in school. There is no other way to obtain an associate degree or four-year bachelor degree in prison in Louisiana. Prison is about time, relentless and banal, and Erica has the relative luxury of spending her days in the chapel, in class, and in the computer lab or library.

LCIW is a decrepit facility with squat whitewashed buildings that is meant to hold 1,098 but is currently bursting with 1,200 women. Simply to give women at the prison something to do, the administration sends hundreds of them to pull grass, what they call “goose picking.” On the day I spent there in early May, it was sweltering by noon. As I walked along dirt paths toward the chapel with Dr. Miller, I saw clusters of women vying for a bit of shade, plucking idly at the sparse lawn, already shorn to a half-inch or less.

Erica will study English Composition, Math, and World History, but the college degree is secondary to the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary’s ultimate purpose: widespread conversion. The seminary’s mission is to win unbelievers to Jesus. It hopes Erica and others will become emissaries of moral rehabilitation and “evangelize their peers within all areas of the prison and other institutions of the Louisiana Department of Corrections.”

In just a few years, ministry students have founded fifteen prison ministries that include visiting and sharing the Bible with women in solitary confinement, counseling the elderly, and teaching a biblical parenting group. Sheila, a current student and self-described former lesbian, runs “Turning Point,” an ex-gay ministry which she says will lead women “out of the darkness of homosexuality.” As a devout Christian, Dr. Miller insists that any person might be reached by God. She doesn’t mind if women join the program solely for the education, and not their Christian convictions. “Who is to say that even if someone is in something for the wrong reasons that a seed won’t plant?”

Dr. Miller is an elegantly lanky woman in her early forties with wavy auburn hair, a strand of pearls she touches as she speaks, and a wary demeanor. She has a PhD in the Old Testament, with specializations in Hebrew and Greek, which she says is unusual for Baptist women. Most women at NOBTS are encouraged to go into church education or counseling. Dr. Miller’s advisor warned her she would never be hired as a professor despite her academic credentials. Reflective of the chauvinism inherent in seminary culture, a man’s name was listed in the directory instead of hers when she taught Hebrew on the main seminary campus.

During lunch in a sandwich shop in the nearby town, Dr. Miller and the other chaplain, also a graduate of NOBTS, murmured a short prayer before we began eating. They tentatively asked if I too had experienced sexism as a professor. I told a story about an older man whose class ended shortly before mine began in the same cavernous lecture hall. Each day, without fail, three times a week, he’d ask in a booming voice, “Are you really the professor? You’re so young!” as my students filed in. They both laughed bitterly about the wife of a Baptist seminary president in Texas who teaches a class called “How to pack your husband’s suitcase.”

They lamented the conservatism of their own religious denomination. In order for Dr. Miller to become a chaplain, she had to sign an agreement that her chaplaincy would never transfer anywhere beyond the prison. She admits that her true passion is for teaching Hebrew at a seminary campus. There is more than a hint of irony to the fact that she has empowered women at LCIW to become college graduates as an employee of an institution that consigns women to extremely limited roles. In some ways, Dr. Miller is as confined as Erica, her student.

Earlier in the morning class, Dr. Miller had concluded her lecture by reminding the women of verse 31 of Jeremiah: the idea that even under oppressive conditions, their true ruler is God. “As Christians, this should be your big take-home. They write the law on their hearts and have obedience to something on the inside.” For the women in the room, most of them in their late thirties to fifties, being loyal to a liberatory God over an often petty and cruel prison administration is easier in theory than practice.

This is the first time many of the women have been treated seriously as students.

After class, the women drifted to the library or computer room. They were a sea of pink, yellow, gray, and blue t-shirts and prison denim, each woman quietly defying the regulations of sanctioned prison garb. For a moment it seemed they could be an adult education class anywhere. Tensions erupted over the use of the coveted laptop computers. Three women were assigned to each. Like harried college students, they fretted about their papers, due in a few days. Erica was unfazed. She’s been in prison eleven years and has already graduated from Culinary Arts, tutored for the GED, and worked in the hospice program and infirmary. How difficult could understanding the symbolic acts of the book of Jeremiah be?

This is the first time many of the women have been treated seriously as students, challenged to learn a new language or to write English papers that are structurally and grammatically rigorous. “I thank God every day that I came to prison,” an ex-biker named Cynthia told me. “Do I still want to come home? Yes. But, I would never have went to college. I’m in college, girl. I’m in university, and I can do it.”

The vision of a seminary movement spreading throughout the American prison system is the brainchild of Burl Cain, the controversial warden of Angola prison, the Louisiana state penitentiary just two hours north of LCIW. I spent three days in Angola after I visited LCIW. Kathy Fontenot, the associate warden, had allowed me to spend the night in guest cottages within the prison. The sign above the entrance gate to Angola reads, “You Are Entering the Land of New Beginnings.” No one was there to meet me. I wandered into the Angola prison museum, just outside the gates, and found Fontenot. When Warden Cain, a stout, authoritative figure in his seventies with flowing white hair and a penchant for aphorisms, became warden in 1995, one of his first actions was to institute “Experiencing God,” a year-long Southern Baptist Convention program for Christians confronting adversity. Before long 1,600 men had completed it, and now it’s a requirement for anyone who wants to attend the college program.

Congress eliminated Pell Grants for prisoners in 1994 even though they constituted just under 1 percent of students receiving Pell money to go to college. The “tough on crime” atmosphere of the period, enflamed by anti-welfare sentiment, doomed hundreds of prison college education programs throughout the United States, including Angola’s. Almost immediately, Warden Cain solicited religious organizations to teach in the prison. The NOBTS program designated Angola as one of its twenty-one extension sites on September 11, 1995. The program is funded by the seminary, the Louisiana Baptist Convention, the Baton Rouge Baptist Association, and individual donors.

Close to three hundred men have graduated from the program and Warden Cain is heralded by supporters as a miracle worker who has brought order and peace to a previously chaotic and brutal place. For years, Angola’s moniker was the “bloodiest prison in America.” Men slept with catalogs and phone books taped to their chests as shields against stabbing. Wilbert Rideau, former editor of Angolite Magazine, who spent forty-four years in Angola, chronicled rampant rape and sexual exploitation in his memoir and a famous essay, “The Sexual Jungle.”

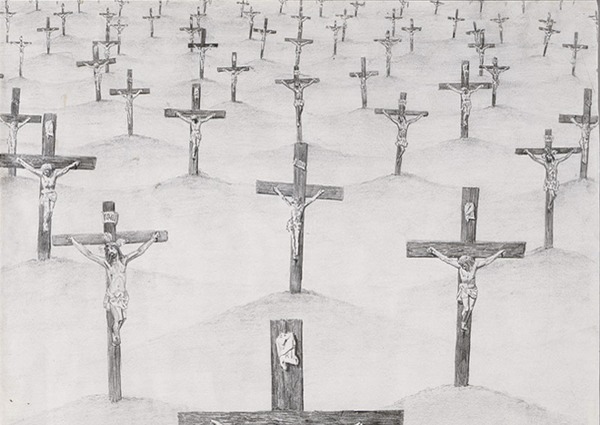

The victorious story that Warden Cain tells about his reign is that turning prisoners into missionaries makes the prison safer for all, and by extension, easier to manage. Unlike secular college programs, the Baptist seminary college, Warden Cain believes, enables men to undergo a spiritual and moral transformation. “Without moral rehabilitation, you’re just making smarter criminals.” For Warden Cain, reforming prisons is a matter of reforming prisoners’ hearts. The idea of a changed heart comes from Ezekiel 36:26: “A new heart also will I give you, and a new spirit will I put within you: and I will take away the stony heart out of your flesh, and I will give you a heart of flesh.”

Along with religious transformation, according to Warden Cain, the program provides men at Angola with purpose and hope. Despair is a prisoner’s most potent enemy. Both the prison administration and the men inside seem to agree on this. Of the more than six thousand men in Angola, more than four thousand are serving life sentences without the possibility of parole. “We have more funerals than we have men going home,” he told me.

Angola is a former slave plantation thus nicknamed because the owner supposed the hardiest slaves came from Angola, Africa. After the Civil War, slavery persisted in the form of the convict-leasing system. Southern legislators, terrified of the political and economic power of African-Americans, criminalized minor infractions like loitering, vagrancy, or eating a pig to re-enslave on work farms those who had been enslaved prior to emancipation. Hundreds of thousands toiled in abysmal conditions and, because they were no longer property and thus considered disposable, many were simply worked to death. The system was so brutal that historian David Oshinsky has called it “worse than slavery.” In 1901, Angola officially became the Louisiana state penitentiary. It is the size of Manhattan.

Angola is still often referred to by outsiders and staff as a prison farm.

No one is picking grass at Angola. Everyone works at something. The dreaded assignment is still in the fields, which stretch for miles, broken only by the immense Lake Killarney, where some prisoners fish. Every day, all year round, hundreds of men march in a line, hoes balanced on their shoulders, to pick beans, okra, squash, cotton, sugar cane, wheat, or corn. None of the more than one thousand guards at Angola carry guns with the exception of the field overseers, mounted on horses, who are armed with rifles at all times.

When I interviewed Robert Mencie, a 31-year-old black man from California who is a student in the seminary program, he recalled his incredulity upon being sent to pick crops when he first arrived. “I didn’t know people were still doing slave-type work. I didn’t think they were doing that in America. Period. Until I come down here.” Angola is still often referred to by outsiders and staff as a prison farm.

The prison trustees hold the most coveted jobs, earned after decades at Angola. These men have inched their way to the upper echelons of the prison hierarchy as automotive mechanics, newspaper editors, radio DJs, cattle wranglers, horse trainers, preachers, heavy-machinery repairmen, coffin-makers, and cowboys who compete in Angola’s yearly prison rodeo. The trustee system is meant to dole out incentives in the face of hopelessness. Prisoners have responsibilities, jobs, and a modicum of freedom within the vast Angola prison empire.

There are no fences in Angola except those encircling the prison housing camps, spread throughout eighteen thousand acres. Wolf-German shepherds raised by prisoners prowl between the double-barbed-wire barriers that surround the camps where men are locked into their cells or dormitories at night. Dense wooded hills teeming with snakes and the alligator-infested Mississippi River form a natural barrier between the prison and the outside world. It is twenty miles to the nearest town, the road lined with ramshackle homes and the occasional decaying antebellum plantation.

Dr. Robson claims the seminary constructs, however tenuously, a community of accountability in a place where no one trusts anyone.

Part of Warden Cain’s bravura is that Angola doesn’t need fences when it has hundreds of men trained as ministers to promote peace, order, and security. No one has more freedom than the seminary students and graduates, except possibly the Angola cowboys who herd cattle. Like the women at LCIW, Angola’s students spend all day in the classrooms, libraries, and computer labs.

The seminary’s morning class is taught by Dr. Robson, the director of the NOBTS’s Angola extension site since it began. Dr. Robson is in his seventies and exercises a disconcerting mix of piety and frankness. He woke me with a 6 a.m. phone call to make sure I could meet him in time for class. Everywhere we walked in the prison, men greeted and petitioned him: “Hi, Doc” and “I sent you a message, Doc” and “See you in class, Doc.” When one man droned on for ten minutes in class, Dr. Robson told him he’d been “shooting the bull” for too long. A veteran preacher and seminary teacher, Dr. Robson relishes upending stereotypes of conservative Southern Baptists. “You can’t peg me,” he said, pointing out his white Prius among the ubiquitous giant trucks and SUVs of the prison staff. He’d planned to retire in 1995 but took the Angola job instead, and he said he has never regretted it.

In his class on the Old Testament, Dr. Robson preached and various men came to the pulpit to expound on various verses. They were reading from a 1935 book of daily devotions called My Utmost for His Highest. The May 6th page derived inspiration from Galatians and centered on the concept of liberty. “There is only one true liberty—the liberty of Jesus at work in our conscience enabling us to do what is right,” which seemed to resonate with the men. They shouted and nodded. Dr. Robson claims the seminary constructs, however tenuously, a community of accountability in a place where no one trusts anyone. The men are expected to protect and shelter each other. During class, Dr. Robson said, “There is a code of not ratting on each other, but not in this place. The greatest force of behavior modification is gratitude to Jesus. Do you want to go to sleep with a Sears, Roebuck catalog across your chest?”

Certainly men are no longer sleeping with catalogs, but despair still seems to lurk everywhere. During lunch, associate warden Fontenot’s walkie-talkie crackled with chatter about an altercation in the yard of the main prison. The cause was an attempt to smuggle in synthetic marijuana from an outside camp during a flag football game. I witnessed two emaciated hunger-strikers stagger into the infirmary and later talked to men in Camp J, the place commonly referred to by prisoners as “where they take you to crush you.” At Camp J, men spend twenty-three out of the twenty-four hours in a day in a cell with only the company of a metal bed and a toilet. Entering cellblock J, we passed men in orange jumpsuits, outside for their allotted forty-five minutes of daily exercise in eight-by-ten cages. Herman Wallace, a former Black Panther accused of murdering a prison guard, whose case has helped ignite a movement against solitary confinement, spent over forty years in solitary in Angola, most of it in Camp J. Conversations with other prisoners belied my sense that seminary men would intervene when someone was being attacked or coerced. One man confided that they have a saying in Angola: “You see, but you don’t see.”

Prisoners whose families can’t or won’t visit sometimes spend years without contact from outside, with what the men refer to as “free people.” They find solace in religious volunteers who show up every week, in services and in the certitude of belief. Aside from family, the members of faith-based groups are the outsiders one is most likely to see inside an American prison. These volunteers reflect the religious landscape of the area where the prisons are located; in the case of Louisiana, Texas, Georgia, and Florida, the landscape is one of conservative Protestant Christianity. Although Quakers were the original advocates of the modern penitentiary model—in the 1800s, prisoners at Eastern State in Pennsylvania spent time in prayer, solitude, labor, and penance as the avenue to a reformed self—it is extremely rare for mainline or progressive Protestants to hold services or studies in prisons today. Conservative Protestants have the monopoly on prison ministry. They fill voids in education, mental health, and addiction counseling as states jettison programs to trim budgets. Many volunteers are spurred by the Bible verse in Matthew, “I was in prison and you visited me.” Rarely do these groups involve themselves in reforming a draconian prison system. Volunteers accept that the suffering and degradation of prison are necessary for redemption. It is individual souls they want to salvage.

Erica is one of those souls. Within a few years of graduating high school in Shreveport, LA, she was addicted to crack. “The only time I was clean was in jail,” she said. “And the longest I stayed clean was six months. Idle time is the devil’s workshop. Same cycle, same cycle.” During these years, she gave birth to her first five children, and struggled constantly to feed and care for them. On one occasion, she stole two pairs of jeans from J.C. Penney and was arrested for shoplifting. There were other shoplifting charges for clothing and food. She continued to have more children as she moved in and out of jail.

In spring 2004, Erica and a friend drove to a Kroger grocery store in an old Chrysler with license plates pilfered from another car. Erica had a fake ID doctored to match the name on a stolen checkbook. She loaded up her shopping cart with four cans of Similac baby formula, two giant packages of diapers, t-shirts, and a purse for herself. When she realized the sympathetic cashier to whom she hoped to pass the bad check wasn’t working that day, she rolled the overflowing cart out the door. A Kroger employee chased her through the exit, and she abandoned the cart and sprinted for the car, where her friend was waiting in the driver’s seat.

Accounts of what happened next vary. Erica says she plunged into the driver’s side and tussled with her friend behind the steering wheel. With the door ajar, the car jerked forward. Danny Maguire, a 74-year-old Kroger employee, was stacking grocery carts. The Chrysler knocked him down, ran over both his legs, and kept zigzagging down the street. Employees followed and noted the plate number. At the hospital, doctors treated Maguire for a broken leg and various contusions, but that night he died of cardiorespiratory failure. He had a history of heart disease that was exacerbated by the collision, but the doctor listed Maguire’s death as a homicide. Police found Erica within days. She was deemed a habitual offender by the courts and sentenced to forty-seven years in prison. Louisiana is one of only two states that use juvenile records to show that someone is a habitual offender and therefore merits a life sentence. Erica maintains that she was not driving despite conflicting witness testimony. The value of the merchandise in the abandoned cart was $270.

The God she believes in is forgiving and, unlike anyone else in her life, does not resent, judge, or blame her.

Now, as a seminary student, Erica is determined to do right by her children, most of whom are cared for by her mother and sisters. “When I was on the street, I gave everything to the devil doing his work. I can put forth even greater effort for my good and for the Lord.” Raised primarily by her Baptist aunt, Erica only truly became a Christian once she was in prison. “I didn’t grasp the full concept of what Jesus did for me until I was in jail,” she told me. In a service during her first years in prison, she finally understood what she’d been hearing proclaimed from pulpits since she was a child. “I was in church one night. You do a lot of hollering. But one night I listened and I was taught the word rather than preached the word.”

Erica gave birth to three of her children while imprisoned. One daughter just graduated from high school. Erica said her mother prays every day for God to let her take Erica’s place. As a Baptist, Erica believes in the Bible as the ultimate authority and literal word of God and that she has an obligation to spread the word of Christianity to all unbelievers. The God she believes in is forgiving and, unlike anyone else in her life, does not resent, judge, or blame her.

Louisiana, where Erica is incarcerated in a parish jail, is the prison capital of the US and the world. There are close to forty thousand people behind bars. The state’s numerous parish jails hold almost half the men and women sentenced in the state. All prisoners dread time in the parish jails because of overcrowding, unchecked violence, and a dearth of programs. However, since the 1990s, the parish jail system has become a lucrative enterprise for rural sheriff departments, which secure $24.39 a day in state money for each prisoner. Sheriffs trade and vie for prisoners from New Orleans and Baton Rouge because body counts fund police cars, salaries, and equipment. They “treat us like cattle,” Erica said. The sheriffs’ priority is to fill their facilities, many of which were built in the past two decades.

The web of prosecutors, sheriffs, and private prison contractors is a vociferous lobby against sentencing reform. In Louisiana, prisoners convicted of first- and second-degree murder get automatic life without parole, but the majority of prisoners are in for nonviolent offenses, and Louisiana’s mandatory minimums mean that a person can be given twenty years to life without parole for drug possession or shoplifting. They can also be convicted on the votes of only ten out of twelve jurors. The conservative Texas Public Policy Network, Reason Foundation, and Pelican Institute for Public Policy recently issued a report recommending that Louisiana drastically alter its sentencing. They argue that the state is out of step even with conservative places like Georgia and Texas.

Erica’s desire for education and religious devotion is bound up with her hope that a clemency board or the governor will bear witness to what she has made of her life. However, clemency is unlikely in Louisiana’s current political climate. Between 2008 and 2012, Governor Bobby Jindal pardoned only thirty-six people, fewer than any of his predecessors; he was sent 450 applications for review in that time. When I visited Dr. Miller’s class at LCIW, a few women lingered in the classroom to ask me about women prisoners in Washington State, where I live. When I expressed surprise at how many are serving life, or close to it, in Louisiana as compared to the prison where I teach college classes, Erica retorted, “You’re in Louisiana, girl. You wouldn’t be surprised to see a noose hanging from a tree, either.”

At Angola, the first thing Warden Cain handed me over lunch was a laminated prisoner identification card issued to graduates of the seminary. “Offender Minister” and a DOC number were inscribed on the back. “If we weren’t miracle workers, and we didn’t have this, this place would be rock and roll, this place would be chaos.” With the card, men are able to move with more freedom around the prison and to the outer camps. Whether the missionary experiment will work in other states and prisons depends on prison officials granting authority and privilege to the prisoner missionaries who come from Angola or the women’s prisons. Now there are almost thirty men from Angola serving as missionaries in other Louisiana prisons. The women have yet to go anywhere.

When I met John Sheehan, he was supervising close to forty men inside the Angola automotive plant. He started in the first seminary class in 1995. We sat sipping water in his disordered office, separated from the immense garage by a window. He works on an old desktop computer, the surface barely visible beneath lists, Post-its, calendars, and family pictures. I might have thought I was waiting on an oil change in my local mechanic’s shop except for how he answered the ever-ringing phone: “Automotive. Inmate Sheehan.” And the fact that he makes seventy-five cents per hour as the director, which is considered an excellent prison salary. “I want to be like an outside person. Don’t act like you are in prison, act like you are in society,” he told me.

His mentees spend three months in each section of the garage learning about air conditioning and heating, brakes, electrics, body, steering, transmission, and God.

Sheehan is a white man in his late fifties with thinning hair, thick glasses, and an avuncular, eager manner. He’s lived in Angola for twenty-two years and is quasi-staff in some ways. “This is my church,” Sheehan told me. “Ministry is saving people, not the pulpit.” Since Angola received an influx of close to 1,200 men with short-term sentences when nearby Phelps Correctional Center closed, Warden Cain has developed a mentor program in which seminary graduates are key. The new prisoners with short sentences work in automotive and other industries during the day and take night classes taught by seminarians like Sheehan. His mentees spend three months in each section of the garage learning about air conditioning and heating, brakes, electrics, body, steering, transmission, and God. Eight-five percent will pass the state automotive repair test, and Sheehan is proud of them. “We are blowing the state away” in terms of the quality mechanics they are turning out, he boasted.

When Sheehan graduated from the prison seminary in 2000, they sent him to B.B. Rayburn Correctional Center, 130 miles from Angola, for two years to work as a missionary. After the effort of establishing himself in the Angola prison hierarchy, Sheehan resisted the transfer. “I was afraid I would lose everything I had here.” The rationale for the missionary program is derived from Mark 6, verse 7: “Calling the Twelve to him, he began to send them out two by two and gave them authority over impure spirits.”

Like cranky elders everywhere, I heard Angola trustees complain about the “young’uns.” Rayburn and many of Louisiana’s other prisons house younger men with shorter sentences who have more of a predilection for fighting and gangs. At Angola, which has hundreds of aging lifers, there is a measure of calm and peace for those who have lived there twenty or thirty years. For better or worse, it has become their home.

Initially, Sheehan found Rayburn’s atmosphere anarchic and stressful. Undaunted, he preached and converted others until he eventually created a faith-based wing and brought over seven other Angola seminary graduates. “I was like Joseph,” he told me, shepherding other men to Christ and promoting peace. Two years later, he came back to Angola. Sheehan still occasionally preaches to Angola’s Church of God in Christ congregation. Half of his friends from his seminary graduating class have died.

“Cain’s snitches” is what some Angola prisoners call the seminary students. Warden Cain wants prisoners to monitor each other in an ecosystem of prisoner governance, to quell violence and disorder. Some, like Sheehan, say they believe wholeheartedly in the mission of the seminary. The job of the administration, with its underpaid and overworked staff, is made easier by the prisoner missionaries, who become behavioral exemplars for those around them. I heard over and over from Warden Cain and his deputies that a female officer could be locked in a dormitory with one-hundred men each night and nothing would happen, because the prisoners monitor each other.

Still, granting any authority to a prisoner is anathema to the dynamics of prison. Most correctional officers and prison administrators operate with suspicion first. Many prison officials, including the warden of the Louisiana women’s prison, are reluctant participants in the program. When I briefly stopped by her office, the warden complained about how women are untrustworthy and much more difficult than men because they talk back and argue with staff. Within five minutes of the beginning of our meeting, she told me with evident relief that she was retiring at the end of the month. Like a lot of the prisoners she supervises, she could name the number of years, months, and days she’d worked at LCIW. Remembering a complaint sent in by a prisoner, she told me how they had investigated tirelessly, but found ultimately that the woman had embellished part of the story. “I was so frustrated I told her I’d like to stick a knot up her butt and pull it out through her mouth.” Standing beside me, one of the prison chaplains nervously added, “That’s a Louisiana expression.”

Warden Cain is considered a prison iconoclast for championing a program that places faith in individuals others consider less than human.

Prisoners live with each other for years and see each other every day whether they want to or not. They sleep, shower, eat, and go to the bathroom together. There is no hiding flaws or mistakes. When chosen to become prison missionaries, students know that they will be scrutinized mercilessly by other prisoners. Is he acting better than the rest of us? Does her behavior line up with what she says? In prison, this is the true test of whether a missionary will be successful. There is a lot of talk about women and men who may comport themselves like Christians in the presence of the seminary professors or the chaplain but act otherwise in the dorms.

Warden Cain is considered by his supporters and some prisoners to be an iconoclast for championing a program that places faith in individuals others treat as less than human. Most staff and members of the administration still describe the men and women in prison as “offenders.” Some prisoners refer to Warden Cain as a dictator or “the king,” while others call him “Uncle Burl,” with equal parts affection and derision. Everyone agrees that you do not cross him. Calvin Duncan spent almost three decades in Angola, where he became a sought-after paralegal for death row prisoners. When he arrived at Angola with a ninth-grade education, he had to file a motion to get law books in the prison. Now a Soros Justice Fellow who provides legal documents to men inside Angola, Duncan told me how men flocked to the chapel on the day they knew Warden Cain would be there. As Cain swaggered down the aisle, men surreptitiously handed him carefully folded notes, like supplicants, asking for new teeth or job transfers. By nightfall, most of their requests would be granted.

Murders, suicides, escapes, and assaults on staff and prisoners have crept downward according to a chart Dr. Robson, director of NOBTS, gave me when I visited Angola. Prisoner-on-prisoner assaults have decreased from 743 in 1988 to 195 in 2009. The seminary and Warden Cain are heralded as the heroes of this transformation, and Cain spreads this idea widely. He now consults about similar programs in New Mexico, California, Michigan, and Tennessee, in addition to the programs he’s inspired in Texas, Georgia, and Louisiana.

Staff and prisoners agree that Angola is a less brutal place than it was in the seventies and eighties, but the reasons why are more controversial than the triumphant seminary narrative. As far back as 1952, thirty-one Angola prisoners known as the “Heel String Gang” cut their Achilles tendons to draw attention to the abysmal conditions at the prison. In 1976, Ross Maggio, known as “Boss Ross,” became warden and hired guards with college degrees, fired corrupt officers who condoned rape and stabbings, and brought in more weapons. Even before Boss Ross, the federal government ordered Louisiana to reform Angola after prisoners gathered grievances about racial discrimination in job assignments, abuse by guards, and violations of their civil rights. In the mid-seventies, the state hired licensed doctors (men had been sewn up for years by a prisoner who had worked as a mortician’s helper), constructed new living quarters, and finally hired African-American officers into a previously all-white staff.

Norris Henderson, who spent twenty-seven years in Angola, said of the seminary and Warden Cain, laughing, “If they want to take credit for making the prison safe, so be it. They showed up and the prison was safe.” Henderson is now the director of VOTE (Voice of the Ex-Offender) and a highly respected national advocate for criminal justice reform and policy. While he was in Angola, he worked on legal cases, led the prison’s Muslim community, and founded its hospice program, by which prisoners care for their dying brethren. He was freed after going to court fifty-two times. Henderson is an imposing man with a permanent look of skepticism that disguises his indefatigable kindness and compassion for prisoners and those who have been released. When we spoke on the phone and in person at the annual Soros conference in July, Henderson told me that it was the Islamic brothers, educated men like himself, who improved conditions in the prison long before the seminary arrived. “You survived on the strength of someone else who opened a door for you.”

Then there are the cameras. At the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women, the administration installed security cameras at the onset of the seminary program. When I asked Erica if the prison felt safer after three years, she responded that drug dealing and contraband were less evident, but then hesitated. “Cameras,” she said. “This place has got cameras everywhere. There is a change that’s taken place here, but I don’t know if I see the change from my perspective or the staff’s perspective, if you could say it’s us or the cameras. I want to give credit to God. I hate bringing the cameras up because that sounds like you’re cutting it short.” She pointed up at the ceiling in the room where we spoke. “Look up and you’ll see their domes.”

On my last evening at Angola, I stood with Cain outside the ranch house where outsiders like myself are sometimes allowed to dine with the warden and his staff. Our meals were cooked by Big Lou, a gregarious man with a limp who has served thirty years. For a while, Big Lou cooked in the governor’s mansion. It was twilight, and Warden Cain had arrived late to dinner after driving to town to pick up prescription medication for his wife. His beloved peacocks and guinea hens roosted around us on cars, fences, and trees. As clusters of prison camp lights blinked in the darkness, I heard the night sounds of Angola: the beseeching screams of peacocks and the distant yelps of dogs. Warden Cain urged me, “Tell the truth, that moral rehabilitation really does work. Help us out.”

Warden Cain seemed at pains to assure me that the seminary is not a partisan program, reiterating the idea of moral rehabilitation. He repeated several times that the head of Louisiana’s American Civil Liberties Union had trained him well, and that he regularly calls her on her cell phone. “Forget religion, it’s about morality. As long as it’s fair, I don’t care.”

In an article in Louisiana Law Review, Roy L. Bergeron Jr., a graduate of Louisiana State University and a lawyer in Baton Rouge, argues that the Angola seminary program would fail both the Endorsement and Lemon Tests used by courts to assess compliance with the Establishment Clause, which states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” The Lemon Test, derived from a 1971 Supreme Court decision, Lemon v. Kurtzman, asks the following: Does the government action in question have a bona fide secular purpose supporting the idea that religion should be left to the conscience of the individual? Does it have the effect of advancing or inhibiting religion? Does it excessively entangle religion and government? The Endorsement Test asks simply: Does the government action amount to an endorsement of religion?

Bergeron argues that the Angola seminary requires that men attest to the exclusivity of Jesus and points out that they must take the “Experiencing God” course in order to have the privilege of attending college. The seminary’s stated purpose is to “fulfill the Great Commission,” which is based on Jesus ordering his disciples to spread his teachings throughout the world. This means the mandate of the seminary is to spread Baptist Christianity. In addition, the only men who can transfer to other prisons as missionaries are members of the Baptist seminary. According to Bergeron, the seminary program therefore privileges one kind of religion.

Kyle Herry received a college degree before he was imprisoned at Angola. Now forty years old, he’s been in prison for eight years and has already graduated from the seminary program. Unlike most other students, he’s a Muslim. Kyle reads Koranic Arabic and some Hebrew and Greek, and passionately compares biblical and Koranic commentaries. There have been only a few Muslim prisoners in the seminary program since its inception. Of his early years in the program, Herry said, “I was frustrated, and I was argumentative. I wanted to question everything. I had to understand I was a guest in the school. I had choice. They didn’t force me to come.” Now, he’s resigned. The seminary program hasn’t altered his beliefs, but he’s learned to temper his opinions. Five other Muslims just started as freshman. “I explained to them they shouldn’t be argumentative. Take in the good,” Herry said. “You don’t have to believe what he’s saying, and you can learn from them.”

There are about 180 Muslims in the main prison and close to three hundred in the entirety of Angola, including all the prison out-camps. The prison also has a part-time imam. Warden Cain said, as though it were positive, “We’re the only prison where the Muslim population is going down.” Recently, after becoming disillusioned with the imam, Herry attempted to hold a Muslim study session in the prison yard, but the administration shut the group down. “Security disapproves of a new group, thinks it is terrorism. If they did more research and study, maybe they could reconsider. If this were a Christian group, it would be fine. They have no knowledge of Islam. They don’t want groups fighting against each other. But we can have all kinds of Christian groups, right?” The state of Texas is being sued for not providing adequate services for Muslim inmates. I asked Warden Cain why he hasn’t built a mosque alongside so many new chapels, and he replied that he simply couldn’t raise the money from the local Muslim community.

Cain receives dozens of requests to visit the prison from religious groups drawn to Angola’s notorious past and the prominence of the Baptist program. Ministers who can brag that they have ministered to the worst of the worst hold a certain prestige. Many outsiders come and stay in the three guest cottages perched on a hillside near the prison golf course. But Warden Cain is pickier about allowing religious groups inside to hold services. He admits “inmates are better preachers,” and there are plenty of them. He also wants to know whether these faith-based groups will aid in reentry to civilian life. Despite his unbending faith in the seminary as the vehicle of moral transformation at Angola, he also must attend to issues like prison overcrowding and old men dying.

“Spiritually speaking, we’re all in prison until we get that card from Jesus Christ, get out of jail.”

In the past fifteen years, there has been frenetic construction at Angola. Before I visited, Henderson, the director of VOTE who goes back to Angola frequently for Muslim services, told me sardonically, “Everywhere you walk is a chapel and chaplains feel good about themselves.” The main prison is dominated by a large Protestant chapel with an organ donated by George Beverly Shea, an organist and a gospel singer for Billy Graham for many years. Across the way, prisoners and staff have dubbed the new Catholic chapel “the Alamo” for its pinkish stucco and mammoth size. When I visited, men in the prison Latin American club were touching up the elaborate murals behind the altar. A hologram painting of Jesus worth $30,000 was hung nearby. Dedicated in December 2013, the entire Alamo was built by prisoners in thirty-eight days with funds raised by Warden Cain. Their skill and labor is visible in the painstaking craftsmanship of the wood-hewn pews, stained-glass windows, and the gleaming red-and-white tiled floors. Of the faith-based groups, Henderson said, “Why don’t they build opportunities for guys to get out?”

Almost four years ago, Warden Cain pushed through the appointment of Sheryl Ranatza, a former deputy warden at Angola, to chair of the Louisiana Board of Pardons and Parole, and he has supported changing the law to make wardens ex-officio members of the board. Ranatza, who knows the men at Angola intimately, can now talk personally and persuasively about them when they come up for commutation or parole. Warden Cain and Henderson find some accord in their frustration with Louisiana’s sentencing laws and powerful sheriffs. At dinner one night during my visit, Cain rose abruptly as he listened to someone describe what had transpired in the legislative session that day. The House passed a bill that would continue sending prisoners to parish jails. “Terrible, terrible. This is just about giving money to the sheriffs,” he complained. “We’ll have to try to defeat it in the Senate.”

Henderson said of the seminary, “Are you giving people the help they need or the help you think they need?” When Erica graduates next year, she’ll be trained to counsel and preach the word like missionaries everywhere, but she also wants to go home. There is the time and the crime and the remorse for both. Every person I met seemed to balance their own reform with the possibility of a new life outside of prison.

Dr. Robson tells the students, “Spiritually speaking, we’re all in prison until we get that card from Jesus Christ, get out of jail,” but Erica Bowers and John Sheehan may be locked up for the entirety of their lives. Redemption as a missionary doesn’t lead to actual, physical freedom. “Their chance of a pardon is very slim,” Henderson explained. “Nobody has really benefited from the seminary because their chance of a pardon depends on their crime.”

Warden Cain said the sign at the entrance to Angola means “we don’t care about your past, we care about what you become.” Certainly, prisoners can fashion lives as missionaries, but to Erica and all the others who still talk of freedom—of their cases winding laboriously through the courts, of miracle pardons, of lifers who have gone home—being a missionary in prison is a qualified life. Erica teeters between tentative hope and resignation. “They don’t believe in second chances. It’s always the nature of the offense. That’s never going to change. That’s always going to be before me. But when are you going to forgive me for it?