“Storytelling gives us the power to bring order to the chaos of the real under our own sign, and in this it isn’t very far from political power.” – Elena Ferrante

The Russian brand of fake news arrived in my life this way: In late June 2014, I was trading loving emails with a man I had been seeing. Travel had separated us, and we anxiously anticipated our reunion. These messages were sweet, down to noting the reverberation of shortening proximity.

On the eve of my return, he sent an email with an entirely different tone. He had dined with a friend. The friend had enlightened him about how the US had wronged Putin by essentially forcing him to invade Ukraine. After the dinner, the man I was dating had begun scouring the internet for more clues. He had no personal links to Ukraine. He worked in a mom-and-pop business in Brooklyn.

What he went on to express was not just an opposing political viewpoint, but an entirely new way of being: arrogant, judgmental, projecting evil impulses on everyone. He told me all major news outlets had conspired to deceive the American people with treachery and lies. Obama was party to the evil. It was “inarguable.”

The moment I read the words, I felt he had been abducted. We fought about it. He provided sourcing, among which was RT, the state-run Russian television station.

Years later, when US reporters pieced together the first signs of Russian interference in the US elections, they noticed a Ukrainian minister had popped up in a May 2015 Facebook town hall to beg the company to create a verification process for Facebook accounts. The year before, someone had been fabricating false accounts for Ukrainian officials and posting misinformation. After begging Facebook to take action and receiving no response, the real-life officials had joined the town hall in desperation. When six publicly known Russian-linked Facebook pages were later studied, it turned out they had posted 340 million times. These were only six of the 470 accounts linked to Russian operatives. How many times had the other 466 posted? Twenty-six trillion? Twenty-five English language news outlets had also been targeted to push out misinformation.

Russia had geopolitical goals. I knew from interviewing cybersecurity experts that international hackers punched in to do their work like regular employees, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. My happiness with the man I was dating was only collateral damage. I tell this story because it broke my heart. Today, love has become a casualty of propaganda everywhere in the United States. Friends de-friend. Families exchange messages in capital letters and then block.

A cop once told me that, in a chase, the officer in pursuit is not supposed to make the arrest. His adrenaline is running too high for rational thought. Embarking on a scavenger hunt for information—going down the “rabbit hole”—can apparently make a person more likely to believe propaganda because they become not just a recipient of information, but a “truth seeker.”

Propaganda is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view.” What that definition misses is that this “information” can be plain lies, complete fictions. When Joseph Stalin began the Soviet propaganda office in 1923, he dubbed it dezinformatsiya. The Western name was meant to indicate a false origin—a shape-shifter from the start.

During the 2016 election, many Democrats marveled that Trump managed to gain traction, not from kindness, but from ferociousness. Did this mean the long-held human admiration for selflessness had disappeared? Where were we headed if such virtues were gone?

But then I remembered. Early in the 2016 campaign season I had corresponded with a friend about why he supported Trump so heartily. In response he showed me a post, allegedly written by a veteran, describing how Trump had rescued the then-soldier and his platoon from Saudi Arabia in 1991 after Desert Storm. By the soldier’s account, the US had abandoned the forces, hot and underfed, in a place far from home. Then one day, a TowerAir plane arrived. The soldier in the post said he later learned that Donald Trump, a private citizen, owned the airline and had sent it. Trump had done what the government could not, this soldier said—care for the essential needs of its military personnel.

Certainly an anecdote like that would compel people to admire Trump, I thought. Even one iteration of that post had 75 thousand shares. Then I checked its veracity: Trump didn’t own TowerAir. After Desert Storm, the government booked private aircraft to bring home soldiers because military planes were carrying cargo. Trump had nothing to do with the rescue. The deeply generous act had been ascribed to a man who never did such a thing.

To my friend, I pointed out the problem. He took down the post. He still supported Trump. I have no idea what posts he saw every day. But it struck me that it wouldn’t be the hate propaganda that would gain traction on social media, so much as these fake laudatory posts. They would seal the public affection that would carry Trump forward.

Ultimately, the plane story shifted. In May 2016, Sean Hannity unearthed a 1991 story told by a veteran about Trump yet again bringing Desert Storm soldiers home, this time from a North Carolina base to Broward County, Florida, on his private planes. Trump’s press office confirmed the story was true. This grateful veteran took the stage at a Trump rally in Houston to tell his tale. But when the Washington Post investigated the story, they found that it was not Trump’s private plane that ferried the soldiers. It was a Trump Shuttle Fleet plane, which Trump didn’t even own at that moment in history. Bankers had claimed the fleet to settle debts.

Other stories circulated about Trump’s kindness. Some were true, like a large check written to a citizen who had done a good deed. But there were many false claims. Trump did not pay the mortgage of a man who fixed his flat tire. He did not personally send the son of a terminally ill Mexican American former beauty queen to college; Trump’s equivalent of GoFundMe, called FundAnything, paid for the schooling—in other words, his supporters paid the bill. (Trump has since dropped any association with FundAnything).

New stories about Trump’s supposed virtue began circulating. For a while, the messaging became, “Look at all he gave up to serve our country.” A wave of public gratitude swept the ranks.

I recognized in this false messaging the tricks of screenplay writing. A screenwriting how-to book, The Idea, instructs writers to include early moments of selflessness by the lead character, to make that person more likable. This will build affection that makes viewers root for this character through the final credits, no matter who tries to take the hero down. Another guide, A Writer’s Journey, recommends including something the author titles “The Refusal of the Call” as the third stage of Act One. In it, the protagonist considers all that could be lost if he presses forward, but continues anyway, sacrificing his well being for the greater good.

Once you get to Act Two, the lead character requires foes to keep the narrative moving. At that point, every character that tries to corral him is, by opposition, a villain: from Justin Trudeau to The New York Times.

This script was set in motion a long time ago.

“When you give people too much information, they instantly resort to pattern recognition,” said Marshall McLuhan in 1968.

Modern American life requires conscientious adults to know so much. Obviously, we must fully internalize our professional requirements—from case law to how to work the register. If self-reflective, we should know our frailties and strengths; in a relationship, we should know our mate’s hopes and needs. As parents, we must absorb our children’s dreams and their worries, along with the names and reputations of their friends, teachers, and coaches. To be good citizens, we should know the names of our elected officials, and beyond that, the leaders of other countries and the elected officials in other states. We should be able to recognize and name our prejudices.

Trump, by his attempts at legal overreach, forced concerned citizens to expand knowing to godlike levels. To accurately monitor him, we had to memorize the full cast of characters in DC, the details of bills and executive orders, the web of money, the salient events in foreign battles and trade disputes. Politically active people had to learn when marches would be held and what means they could employ to avoid getting hurt, not to mention what legal action they could take if arrested. We were also supposed to understand not only the thoughts and moods of people in far-flung states, but how their problems might or might not be solved.

“I used to think that everything is understandable if you know both sides,” I wrote in my journal when I was in college. “Now I think it’s the opposite.” That was before I knew pretty much anything. The mind can only handle so much nuance. Faced with doubt, it freezes.

About six months into the new administration, my whip-smart 87-year-old aunt, who had voted for Trump because of his anti-abortion stance, told me she was disillusioned. She lives on a cul-de-sac, in a house piled with newspapers and magazines, from which she surfaces the most intriguing stories. On the phone, she wondered if the trouble with Russia began during World War II. I imagined her red house, the center of bewilderment, while all around, motivations as big as planets—and as mysterious—tugged at her.

Early on in Trump’s political rise, I—as a longtime journalist—was determined to be open-minded. I watched the full videos of Trump’s speeches. I read the complete transcripts of his interviews. I clicked through on Trump supporters’ posts to see their side. I researched their claims. I went to right-wing sites to ingest that view. I went back and read old profiles of Trump from before he was running, to see if I could glimpse something that would counter the alarm I felt about his broadsides and divisive rhetoric.

In his long speeches, Trump could be charming, sometimes almost generous. He spoke of the concerns that worry people in most every place: blight, lack of jobs, high health insurance bills.

But he also conjured so many false demons. No matter how much I strained to understand, he could not come out well in the non-partisan assessment usually favored by the press. Investigations by journalists made him angry. He was used to being boosted as a celebrity, not analyzed as a candidate.

From the stump, he declared journalists “absolutely dishonest. Absolute scum.” As a freshly minted president, only a few weeks into office, he famously called the New York Times, CNN, NBC News, and “many others” the “enemy of the people.”

Hate’s pleasure comes from narrowing your world to a more manageable size. It’s the difference between living in a cozy house and residing in an airplane hangar. If you wall off whole sections of the world or society, you bring caring down to proximity. You don’t even have to think of those despised people or worry about their suffering. Many people don’t want the exhaustion that comes with empathy. It’s a kind of segregation in the mind. It’s the higher-stakes version of “What Happens in Vegas, Stays in Vegas.” There is relief in not having to think of another person’s pain.

For the last 17 years, PBS was chosen as “the most trusted source in news.” PBS paid for that poll. CNN calls itself “the most trusted name in news,” but that was based on a Pew Foundation poll from 2002, an accolade almost twenty years old. More recently, the Pew Foundation found that CNN is the most trusted news source for Democrats, and FOX News the most trusted for Republicans. As of late November 2020, Trump, as president, had tweeted about CNN over 224 times. In some 122 of those tweets, he called CNN “fake.” In the rest, he insulted the network in other ways, or he praised them for covering one of his live feeds.

In March of last year, Trump’s reelection campaign sued CNN for libel. The campaign cited a June 2019 CNN opinion piece by a former Federal Elections Committee general counsel that alleged potential ongoing Russian election interference. In November, a federal judge dismissed the case, stating that the general counsel did not demonstrate malice. Trump’s campaign also sued the New York Times and the Washington Post. Trump is the first president since Teddy Roosevelt to attempt a libel case against a news organization. The main result of these libel cases is to cost these news outlets money and time defending themselves.

Declaring news “fake” is a firebomb allegation. It does not distinguish which story or which fact is allegedly “fake,” and so is impossible to defend against. It is like leveling the accusation of “stupid.” By the time the insulted person says, “Why am I stupid?” the insult has been borne into the world twice.

On the other side, defining one’s news operation as completely trustworthy puts an unrealistic level of guarantee on an extremely complex function. In a major news outlet, a large group of humans labors under deadline to tell of the events that their sources—at least the ones who will talk—witnessed. Humans deliver the news, as effectively as humans deliver healthcare: sometimes very well, sometimes off the mark. Both are worlds of complex organisms—people. The political climate drives humans to promise god-like abilities, simply so we can discuss the problems of the world and how we might work to fix them.

There was a time in my youth when I thought life’s biggest problem was its lack of magic. I had come to recognize that a person couldn’t climb through a mirror and carpets didn’t soar into the sky. Since the night long ago that I woke to my mother’s knuckles crawling under my pillow to extract my lost tooth, I regretted having too enthusiastically loved the myths orchestrated for me as a small child. For my first five years, I was encouraged to believe, to hope for a fantastic world. After that, I waited for reality to break its grid.

The fraud ran deep and was well planned. Illustrators labored; department stores paid men to put on red suits; people crouched behind walls, their hands shoved into a pocket of cloth that sang and answered back.

For an adult, a child’s belief in the Tooth Fairy or talking puppets is adorable, a testament to youth’s innocence. But the moment a parent decides that the child is too old to have a teddy bear, that child must decide which is true: either a teddy bear has feelings and must not be abandoned (as encouraged by picture books and parents, until they suddenly decide to drop that storyline), or carrying a bunch of sewn cloth around is a sign of immaturity.

“Ghosts and monsters don’t exist,” says an annoyed, sleepy father, walking his son back to his room as he cries. “Now go to sleep.” The Harry Potter book he read aloud sits on the bedside table.

I awoke in my childhood with similar fears. And why not? Everything I read, heard, and saw convinced me that the world could crack open at any moment to the miraculous.

The game of deception starts out as a joyous one.

In earlier generations, a moral could exist without real-life experience as proof. Always tell the truth. Do not judge. Treat others as you would like to be treated. If proof were supplied, it was in the form of fables or parables.

Fables are performed by foxes, ravens, geese, frogs. Parables by harlots, bridegrooms, blind men.

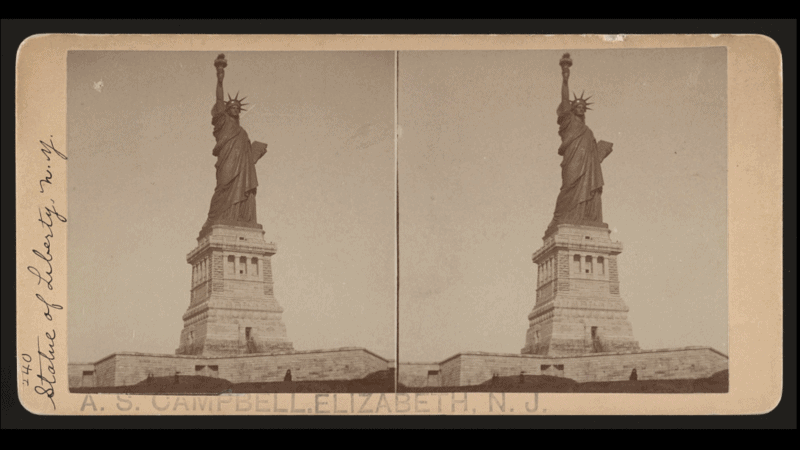

In reviewing historical material in my work as a writer, I noticed that for a good two hundred years, popular versions of US history tended to be nuanced. Then around the 1980s, that seemed to change. The telling tended to be a set of facts gathered around a pre-conceived message. For example, in older coverage, journalists or authors generally acknowledged that the creation of the Statue of Liberty had been fraught. It had been the struggle of one man to create a colossus in the face of general apathy. But in the 1980s, texts tended to tell the story as if it had been a simple gift from the French to the Americans. The message emphasized how beloved Americans were. Another nation rushed to give one of the world’s largest love tokens!

FOX news tells narratives about socialists, Black Lives Matter protesters, mobs, an armed St. Louis couple. Business Insider reported that FOX used old riot footage in June 2020 to lead viewers to believe that cities continued to roil well after protests had returned to peace. The idea of cities at war preceded the fable.

As much as we would like to think of ourselves as savvy consumers of information, we have the instincts of babies. When picking covers for a national magazine, the staff ran focus groups where people inevitably fell for a human, fairly close up, staring at them, preferably a woman (hi, Mommy!).

Propaganda and love both work on deep-rooted, instinctual emotional triggers, answering essential needs and long-held beliefs. The core reason for believing in a passionate love is the deep hope that one is worth loving. A betrayal is the horrifying confirmation that one is not. The core reason for believing propaganda is a deep kernel of fear—say, the belief that another person wishes not only to modify or differ from your agenda, but to destroy you—and the hope of a savior from that fear. Can a human process propaganda’s betrayal? When its lies are uncovered, will citizens cry in the shower? Will they stop eating? Will they close the bars?

The historian Stephen Ambrose once told me that an important first step in his work was to understand that almost no one sets out to do evil. They consider themselves heroes, however mistakenly. His job was to consider the hero narrative that a historical figure superimposed on their lives.

Fiction is considered a useful way to cultivate empathy for others. But propaganda puts the targeted person not outside the action, but in it. It figures out how to cast the reader or viewer as a hero in a narrative that the creator of the propaganda hopes to compel.

For example, in 2018, the Russian account @PoliteMelanie posted the following, which received over 90,000 retweets: “My cousin is studying sociology in university. Last week she and her classmates polled over 1,000 conservative Christians. ‘What would you do if you discovered that your child was a homo sapiens?’ 55% said they would disown them and force them to leave their home.”

The person reading that tweet is enticed to cast themself as a person empathetic to a fight against anti-gay bigotry. With that empathy fired, the reader recirculates a false post that attacks the intelligence and empathy of conservative Christians, thus spreading bigotry.

A misstatement, an exaggeration, an off-the-cuff comment becomes fake news through its amplification, or by assigning purpose when there is none. With the Iraq War, for example, the information that Iraq had purchased aluminum tubes to be used in an atomic centrifuge could have been one data point left behind; experts at the time disputed its accuracy. But the sifting mechanism within George W. Bush’s administration amplified the information as being of key importance. The desire for war elevated an outlier data point.

Even when we attempt to let information craft our understanding of events, the data available dictates our judgment. On a work trip to the Philippines, my reaction to the powers that be manipulating the local population’s fate shifted as I accrued information: When I first saw the brand-new highway reaching to a high-rise construction site far from the poverty-dense city of Cebu, I felt the project was suspect. The billboard that advertised the future condos depicted a family of bike-helmeted white people, paused on a ride. The new development would offer a safe haven for expatriates. I wondered, Why would the municipal government sign off on something so clearly messaged to exclude locals?

Then I learned that the locals liked the project. The developers were constructing a university arm out in this new zone. Local people wanted to study in that peaceful place, far from the city’s slums.

But then I was told that the developer was Chinese and employing only imported Chinese labor. The road had been laid out without municipal input. The location would impact the city forever, yet the foreign investors hadn’t cared enough to work with city planners.

Even then, though denied jobs and saddled with a highway that hadn’t been woven into their city, the locals embraced the development because it included a massive mall. Since the city government set aside virtually no green space in the old city, citizens had come to prize the indoor expanse of emptiness, the retail pastoral. “Filipinos love to shop,” my Filipino friend told me.

The development sat along a fine white sand beach—potentially a lovely place for locals to enjoy, but it was littered by garbage, probably dumped at sea and born to the shore on distant currents. The new developers would clean it up.

My constant reinterpretation of the narrative could only be possible because of an off-balance power structure. If the well-being of the local citizens had been top priority, perhaps they could have had a clean beach, a peaceful university, jobs, and a highway that was theirs. My wavering interpretation could only occur because someone was always winning and someone else losing. A win-win situation holds a steady narrative. It is less vulnerable to propaganda. The physical reality in Cebu was out of alignment with human compassion, hence the fluidity of my interpretation. It teetered.

When I was about ten years old, the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh’s baby haunted me. I had read about the “crime of the century” and would lie awake at night, imagining the ladder against the suburban house, the wind rattling bare branches, the baby in its crib in a high-ceilinged room as dark as mine. I read about the ensuing search. The authorities finding the crushed, dismembered corpse in a shallow grave.

In the middle of one night, I went downstairs to seek solace from my father, who happened to be suffering from midlife insomnia. He was reading and watching TV. I was worried I would be stolen like the Lindberghs’ baby, I told him.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I’m not important enough for you to be stolen.”

Many years later, I learned of theories that Lindbergh had either killed his own baby or collaborated in the kidnapping. The baby had disabilities, and Lindbergh harbored eugenic aspirations. When I heard of these theories, I considered that maybe what troubled me so much was that I sensed the possibility of his lie. What made me shake was the possibility that someone would make up a story to cover his misdeeds. That the truth would be so bad, a baby would die. His own baby.

More recently, I learned that investigators and judges who reopened the evidence believe the baby truly was kidnapped.

So the explanation for the childhood terror comes down to something far more basic: When Lindbergh was downstairs reading that night in his New Jersey home, he heard a strange clatter. Only hours later, did he realize his baby was gone. It was just simple identification on my part. My father read downstairs in our Tri-State home, as I listened for a ladder against the shingles.

When Calexit—the idea of California seceding—gained traction in the wake of Trump’s election, I examined the website promoting it. The first step, the website said, was to amend the California Constitution to remove the part that said the US Constitution was the “supreme law of the land.” A screengrab claimed to illustrate an important point: that the language linking California’s Constitution to the US Constitution had only been added in 1972, so was no big deal to remove. I considered it a big deal to dissolve the binding relations of the Constitution, so I checked the state constitution and found that the language had been in place since its drafting and subsequent ratification in 1879. So the website had lied. The lie made me look up the people behind “Yes, California!” One of the founders was still living in Yekaterinburg, Russia.

When you lie, it’s because you want something you could not get through honesty.

A lie is a fiction made up to take away someone else’s power.

Trust: We all claim we don’t have any. But we do. It’s the flicker. The desire to believe in each other.

Walter Cronkite, “the most trusted man in America,” delivered the news from 1962 to 1981. At one point he participated in a morning news show where he held conversations with a lion puppet named Charlemagne. “A puppet can render opinions on people and things that a human commentator would not feel free to utter. I was and I am proud of it,” he said. But why did we trust the puppet?

Trump’s first tweet using the term “fake news” came in December 2016: “Reports by @CNN that I will be working on The Apprentice during my Presidency, even part time, are ridiculous & untrue – FAKE NEWS!” Over the next four years, he used the term in more than 900 tweets.

From the National Domestic Abuse Hotline website: “Once an abusive partner has broken down the victim’s ability to trust their own perceptions, the victim is more likely to stay in the abusive relationship.” The organization’s guidance on “emotional and verbal abuse” continues:

“Gaslighting typically happens very gradually in a relationship; in fact, the abusive partner’s actions may seem harmless at first. Over time, however, these abusive patterns continue and a victim can become confused, anxious, isolated, and depressed, and they can lose all sense of what is actually happening. Then they start relying on the abusive partner more and more to define reality, which creates a very difficult situation to escape.

In order to overcome this type of abuse, it’s important to start recognizing the signs and eventually learn to trust yourself again.”

In his 1961 book, Rhetoric of Fiction, Wayne C. Booth coined the term “unreliable narrator,” though examples of the form existed going back to ancient texts.

In his 1961 essay, “My Built-In Doubter,” Isaac Asimov defines science as “a system of ‘natural selection’ designed to winnow the fit from the unfit in the realm of ideas.” Science is by definition a grinder that submits ideas to extensive tests, criticism, mockery, and questioning. The Union of Concerned Scientists, a more-than-50-year-old organization founded at MIT, documented 150 anti-science moves by Trump. Under review, they fit a pattern. They evidence contradicted Trump’s storyline or desires.

When you wonder why people don’t notice how terrible someone is, it may just be that they haven’t yet worn out the person’s use in another storyline that they are scripting. For example, they may be scripting a story that the abusive partner will finally see the light.

As a high school and college student, I harbored a visceral dislike of Ronald Reagan—his vocal cadence, his corny jokes, his seeming insincerity. Network TV or mainstream newspapers and magazines delivered the news in that era. Aside from the Village Voice, I had little access to information that deviated from the storyline that, while Democrats or political activists might express substantive disagreements about his policies, the man was generally respected. No amount of reading, however, could deliver to me that respect.

Then, traveling in Hungary in the late 1980s, I met a local girl my own age who told me that when Reagan said, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall,” it had shifted the psyche of her family and friends. Life might be different, they realized.

I granted Reagan a grudging regard because of her testimony. My peer had experienced a direct, positive effect from what I considered posturing.

The Washington Post reported that Facebook executives half-apologized for missing the fake news onslaught endured by Ukrainian officials in 2014. “We are working here in Menlo Park,” said Naomi Gleit, Facebook’s vice president for social good. “To the extent that some of these issues and problems manifest in other countries around the world, we didn’t have sufficient information and a pulse on what was happening.”

When my children were small and mid-tantrum, speaking sassily, rolling on the floor, I would request, “Please say it to my face. Look me in the eyes and tell me the same thing.”

I assumed that while they could easily rail against an imagined version of my authority, they could not actually insult the person who—however imperfectly—had been there when they were sick, or squeezed their hands on walks to school, or kissed their stuffed animal when they demanded the bundle of cloth be kissed. And perhaps, too, they saw themselves in my eyes and could not be cruel to themselves.

It’s striking how much Trump can soften in the presence of a person he railed against. It was most on display with President Obama. Trump had spent the better part of six years attacking the man, most famously in the “birther” controversy that Trump manufactured in 2011.

Then the two met after the 2016 election. A scheduled ten- to fifteen-minute conversation stretched to an hour and a half. Obama’s presence converted Trump into an admirer. Trump told the press afterward he had “great respect” for this “very good man.”

It didn’t last long. A few weeks later, Trump’s tweets began to trend mildly negative against Obama. By March 4, he raged that Obama was a “bad (or sick) guy” for what was repeatedly proved to be a false allegation—that he allegedly wiretapped Trump during his campaign. Still, it remains important that when Trump had Obama close, he could not hate.

“It’s very hard to hate someone when you’re face to face, or voice to voice, with them,” said Dylan Marron, host of the podcast “Conservations With People Who Hate Me,” in an interview during Trump’s first year in office. “Once you hear someone’s story, once you ask them that magic question that opens a lot of doors—‘Why do you feel this way?’—the world opens up a little. There’s a McGuffin in every conversation—whether it’s the 18-year-old who told me that he was bullied all throughout high school and that the things he said to me were similar to the things his bullies said to him, or the person who told me to kill myself, then revealed that he attempted suicide when he was a teenager.”

In We Were Eight Years in Power, Ta-Nehisi Coates cites Gerry Fulcher, a white New York police detective, who became impressed with Malcolm X after listening to him when wiretapping him.

A New York City hostage negotiator practiced close listening with an elderly woman armed with a 10-inch butcher knife: “Despite her profanity, my partner was able to detect something else. He said to her, ‘Martha, I can hear your pain. I hear it in your voice.’ And she went from ranting and raving to absolute silence.”