“The archive … is the border of time that surrounds our presence, which overhangs it, and which indicates its otherness; it is that which, outside ourselves, delimits us.”

– Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge

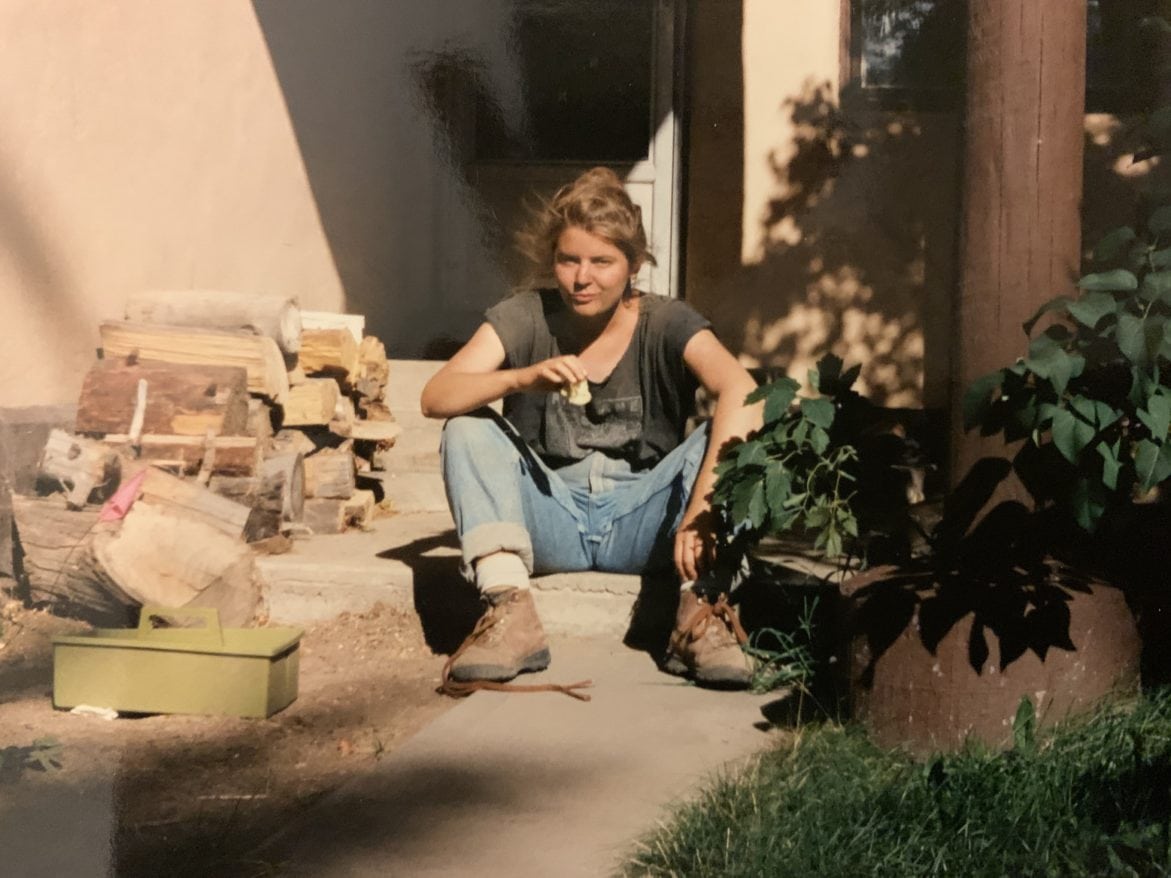

At twenty, I took a job with the Forest Service. I accepted the offer over my dorm room phone and made arrangements to fly from Cincinnati to Durango after final exams, all of my hopes for the summer squeezed into my dad’s ancient, external frame backpack. I was hired to work on an archaeology survey crew, and was certain that this meant I was finally stepping into my adult shoes. When I deplaned at the county airport on the first day of June, 1992, I was incandescent with delight.

By seven the next morning I stood with my fellow interns in the meadow below the Falls Creek Rock Shelters, a two-thousand-year-old site just a few miles outside of Durango, Colorado. The four of us were lined up along one edge of the field, fifty meters apart, ready to embark on our first-ever archaeological survey. We had just been instructed in the basics: how to take long, slow steps, searching the ground in front of us for artifacts; how to measure our paces so that we could keep track of how much ground we’d covered; how to think of a field as sliced into survey transect lines, covering it like shading on a map. We were young and eager, in college or just done.

My fellow interns were testing archaeology as a career path. My aims were less practical: I wanted to immerse myself in the people and places that I had been reading about all spring in my Southwestern Archaeology class. When our bosses explained that the Falls Creek Rock Shelter site had been excavated in the 1930s by Earl Morris, I gasped in delight: I recognized the name from my textbook. Real archaeologists had walked this ground, and here was I, following in their footsteps. I bent to pick up a bit of odd rock. “Is this a piece of pottery?” I asked my boss, an archaeological technician for the Forest Service.

She didn’t even need to touch it. “Quartzite. It is a flake, though—see that sharpened edge? It’s a chip left over from making a stone tool.” We fanned out to see if it had a companion, which would make this a recordable find. It did not.

“Good eye,” she assured me, and tossed the flake back into the grass.

I had a deeper desire, too. Well-versed in the facts and figures of Southwestern archaeology, I still felt something lacking: I hoped I would be able to touch the past here, to commune directly with the ancient Puebloans.

I kept this desire to myself. Instead I watched our bosses, seeing if their work brought them closer to the kind of connection that I sought. From what I could see, though, their work consisted mostly of logistics. With so much national forest and only two of them (supplemented by the four of us), they looked for cultural resources only where another project was already planned—a timber sale, or a campground expansion, or a culvert improvement. Their job was to make sure these projects wouldn’t damage the Forest’s archaeological heritage.

This week’s work was supposed to be an exception: “This is a known site,” they told us. “You’re lucky to be able to start with this.”

I peered harder into the grass, willing my eyes to see something. If this was a good site, how much archaeology would we even find this summer? All morning we walked slowly back and forth, scanning for bits of stone and pottery, and mostly what we saw was dirt. Whatever Pueblo artifacts may have once been here had long ago been silted over or plowed under; no Pueblo people had lived in the valley since the age of Charlemagne.

Back then, the valley floor had been marshy, said Sharon Hatch, one of our bosses. The Pueblo people would have grown some crops here, and gathered wild plants, but the real action was higher up. She pointed to the massive band of sandstone looming above us: that, she said, was the heart of the site. Once there had been a village, and the villagers had buried their dead in rock crevices.

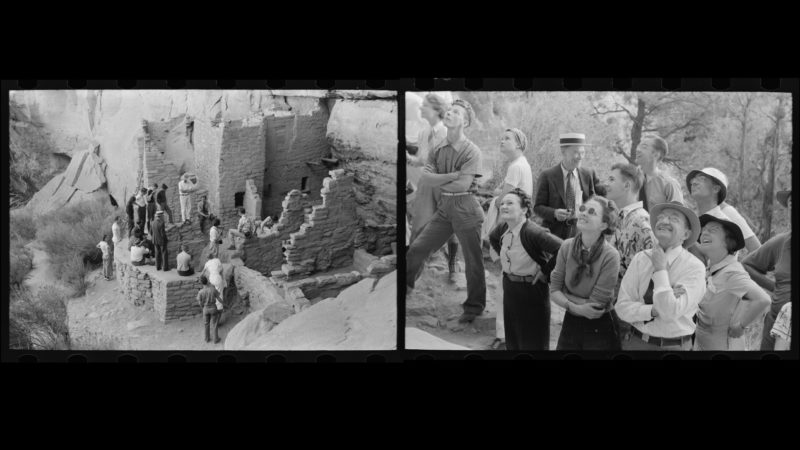

We had to squint. A village? We saw a cliff face. She nodded. There were ledges at the base of the sandstone, where the softer rock had weathered away over the millennia; on these ledges the people had built clusters of domed pit houses out of mud and sticks. The village would have resembled the famous cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde National Park fifty miles to the west, except they would have been rounded and smooth, like little pearls at the base of the cliff. They were, in fact, precursors of those striking masonry towers built one thousand years later.

It was one of the most significant sites in the state, she said, although not very much remained; the rock burials had been looted in the 1930s, and then the Morris excavation had destroyed what was left.

I adjusted my sunglasses and squinted up at the sandstone slab, whipped and crenellated like a layer cake. An ad hoc trail wound up through the oak brush; I wanted to follow it to see for myself. There must be something, I thought. Some unburied rim, some blackened stones, some echo of human life I could connect with. It didn’t seem fair that our “best” site was a hollow shell.

Still, the day was warm and the green of the grass vibrated against the red rock walls of the valley. Snowcapped peaks rose beyond like a mirage. It was beautiful, I was miles and miles from the muggy Midwest, and even if I wasn’t going to discover the next Keet Seel, I was in Durango, doing archaeology. I hoisted my pack like a celebration.

“To many Native Americans, the theft of what is sacred to their community stands as the greatest of all the crimes perpetrated upon them.”

— N. Scott Momaday, 1996

The destruction of the Falls Creek Rock Shelter site began with a visit from New York. Helen Sloan Daniels, a local civic leader who had taken on the duty of preserving and recording the area’s abundant archaeology, wanted to impress an out-of-state friend by showing her the Indian rock art above Hidden Valley. Helen had been there only once before, so they got a little lost. Instead of climbing to the more accessible rock overhang called South Shelter, which in 1937 had already been hit by pothunters, they ended up at the bigger and stranger North Shelter. This overhang lay at the base of the same sheer rock face, but farther north. It cut more deeply into the rock, almost a cave instead of an overhang. The rock art here was clear and bright and the dust was undisturbed. Even better, as they poked around its cool recesses, Helen found a dirt-filled crevice between two boulders. The crevice looked like it was tucked far enough into the overhang to escape even the fiercest weather, meaning that anything buried here would likely be very well preserved.

Helen was new to archaeology, but she had a college education and an indefatigable temperament. In a year of documenting Durango’s archaeology, she had read as much on the topic as she could get her hands on. She’d attended lectures as far afield as Utah and New Mexico, and she knew that the biggest questions in Southwest archaeology concerned the timeline of the earliest Pueblo peoples—known as the Basketmakers, because they didn’t yet make pottery. Of particular interest was the cultural phase known as Basketmaker II, during which agriculture and permanent settlements were adopted—an essential step for the spectacular cultural flowering that came several hundred years later, and somewhat of a mystery: What caused people to settle down and start growing crops? Did the culture represent a new group of people moving into the region, or were cultural traits that originated to the south adopted by local hunter gatherers? Because the Basketmaker II people neither fired clay nor built with rock, their cultural remains were more perishable and tended to be found only in higher altitude caves—like the Falls Creek rock shelters. On that hot summer day in 1937, Helen suspected she and her friend from New York had stumbled onto a very important find. She took several pictures and made careful note of the shelter’s location.

At the next meeting of the local archaeological society she showed off her photos. In particular she showed them to I.F. “Zeke” Flora, a fellow archaeology enthusiast and a local jack-of-all trades who had helped Helen on several excavations and led her to the South Shelter the summer before. “I don’t know where you will dig,” she said to him, “but I will dig here.”

The next day Zeke drove up in his Jeep. Within hours he had uncovered one of the greatest caches of mummified burials in the history of the American Southwest. Helen joined him the next morning, and, by the end of a few feverish days, the two of them had hauled the remains of nineteen individuals and their grave goods out of the crevice and down to a shed on his property.

Helen and Zeke were unlikely friends: She was a Durango Brahmin who was married to the local dentist, and he was a hardscrabble preacher’s son from Ohio. Helen had a college degree; Zeke had barely graduated from high school. But they were united in their ravenous drive to root out every secret of the cave—at least for now.

The pair worked frantically, covering their faces with damp towels to keep out the noxious dust. Zeke dug and Helen sorted: baskets, beads, mats, sandals, awls, grinding stones, twine, flakes of rock. There was so much material that they threw a lot of it aside, uninterested in anything that wasn’t an obvious Find. They uncovered burial after burial. The dry conditions had preserved several of the corpses, and a few were almost completely mummified. They named the bodies as they pulled them from their graves—Esther, Jasper, Grandma Niska—stamping them, claiming possession.

They carried the materials down to Zeke’s Jeep in an adrenaline-fueled haze, up and down the punishing slope in the blazing August sun. Collapsing in the car at the end of the day, they were sweaty, sunburned, dehydrated, and covered in scratches. Still, they spent the ride back to town eagerly discussing how to clean what they found. Helen suggested a vacuum upholstery brush. Zeke opted to spray down the mummies with a hose.

When Zeke decided to keep the entire haul, it seems Helen did not protest or even question him—even though she knew he intended to sell everything. Perhaps she thought he needed the money and believed it wasn’t her place to interfere with his ability to earn it. Besides, he had shown her the shelter in the first place—on private land, they thought, and therefore legally sellable. She did keep one stone-bead necklace for herself, carefully restringing it so that she could forever admire its two-thousand-year-old pattern.

Zeke did need money—it was the Depression and he had a growing family to support—but his approach to selling the goods was ambivalent: he wanted to profit, but he wanted to be taken seriously, too. He sent letters to every archaeologist who worked in the Southwest, bragging about the mummies’ preservation and making the case for their Basketmaker provenance. When the archaeologist Earl Morris finally bought the collection, Zeke was triumphant. Then he spent the next forty years trying to get the mummies back.

Helen has gone down in history as the Good Looter. Unlike Zeke, she didn’t try to profit from the find and seems to have been genuinely motivated by a desire to learn and preserve. But her notion of preservation didn’t extend to leaving burials intact. She almost certainly embraced the values that, a few decades later, would cause white archaeologists to argue that they were better caretakers of the Indian past than Indians themselves, because they would keep it indoors, in climate-controlled boxes.

“It is our hands. They want to touch everything. With fingers like these, the kind that turn pages and pick up the head of a pin, how could we ever call them off?”

— Craig Childs, Finders Keepers

At the end of our first week of archaeological work, we were rewarded with a climb up to the site of the old pithouse village. It was hot, and the ledge beneath the rock overhang was disappointing—brush-choked and littered with fallen rocks. Whatever frisson of past lives I’d been hoping for never arrived, and the dusty place seemed no different than any other rock ledge. We sipped tepid water from our Nalgene bottles and surveyed the view.

I had switched majors from history to anthropology on the advice of my favorite professor, who said the questions I was asking in my papers were much more suited to the latter field. I was flattered, and immediately followed his advice. Archaeology in particular was just emerging from a period of exciting growth, when presumed truths about the human past—that agriculture made people’s lives better, that the life of the hunter-gatherer was brutish and short—were being overturned. I was riveted. I threw myself into the scientific literature of the ancient Southwest, reading about the religious civilization at Chaco Canyon, the exquisite painted bowls of the Mimbres culture, the collapse of the cliff dweller society at Mesa Verde.

Now that I was here, though, the landscape daunted me. Viewed from the distance of my college classroom, the Southwest had seemed neatly defined and contained, a place that could be understood by memorizing cultural stages or the different types of pottery glaze. From my perch at the edge of the rock shelter, I had a sudden disorienting awareness of how huge it was. The site the four of us had spent an entire week surveying was just a single remote outpost, and hadn’t been Pueblo territory for almost a thousand years.

I had thought of Southwestern archaeology as a body of knowledge to be mastered, an art at which I excelled. But now I could sense the patchwork of access and trespass, ownership and exile, that lay over the canyons and mesas like an invisible web. I stood on Forest Service land made valuable by the presence of ancestral Pueblo. I looked out over municipal parks, commercial property, community trails, and private ranches; in the distance was the Southern Ute Reservation. Beyond and in between were the thousands of sites sacred to one Indian nation or another, places a white person could peer into and tread on and even legally buy, but never really enter.

We spent the rest of the summer doing timber sale clearances, just as Sharon said we would. Every Monday morning we packed the mint green government rig and drove up into the hills; we spent the rest of the week slogging through deadfall and cow pastures, scanning the ground for artifacts. It was hot and tedious work, and we got rained on almost every day. We found a few interesting sites, deep within the high, rocky gorges of the San Juan Mountains, but most of the time what we found were indeterminate lithic scatters—a handful of rock flakes in the dirt. You plucked them up, admired the confident skill they represented, and then tossed them back. The dullness of our findings, as far as the Forest was concerned, was just fine. We were hired to be its eyes and little more.

I didn’t want to just be an eye, though. I wanted to be a brain.

“Scientists look at archeological sites as something they can do whatever they want to.”

— Dan Simplicio, Zuni Nation, Cultural Specialist at Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, 2018

Earl Morris was the only archaeologist to respond to Zeke’s appeals. Morris had grown up in the nearby town of Farmington, New Mexico, and knew better than his Harvard-educated colleagues what it was like to be poor and desperate. He had begun his own archaeological career as a pothunter; the money he made from selling burial goods helped his family pay rent after his father’s murder.

He recognized right away that Zeke had scored something unique. That winter he drove down from Boulder and paid Zeke five hundred dollars for the lot, which he packed carefully into boxes and stashed in his attic. Then he started planning the excavation. By early summer he and his family were living in Durango and he was assembling a crew of able-bodied men to help with the dig.

Morris had worked hard to arrive at his station in life: He was a college professor married to an Omaha debutante, with connections and colleagues all over the Southwest. He was most definitely a brain, even if, reading his monograph of the Falls Creek site, you might be fooled into thinking he was simply a pair of mandibles, chewing his way straight through the spiritual landscapes of the Southwest in quest of the edible pith.

His Durango excavation team, which included both Zeke and Helen, destroyed almost everything that was left at the rock shelters. They peeled off the surviving floors of the ancient pithouses, and diligently emptied every grave. They separated every object they found by type. Whereas each person had once lain in a nest of objects meant to aid them in their journey to the beyond, Morris shucked off decaying grave clothes and piled them with other woven things; he lumped the hunting points with the sewing awls, the necklaces with the game pieces. He separated skulls from skeletons and sent them east to be studied by Harvard, while the more mundane objects went into storage at Mesa Verde. He categorized and catalogued every seed, every bone, every bit of twine. His research yielded one of the most comprehensive accounts of a Basketmaker II site available. And yet it is hard not to feel that it entirely misses the point.

“The scientists have had enough time to study the corpses.”

— Mr. Frank Bedonie, Native American consultant, 1997

As the summer of 1992 wore on, I heard, or maybe felt, the whisperings at the edges: how the local Native Americans did not like archaeologists. We were considered predatory, greedy, and culturally insensitive. The type of archaeology I was engaged in sometimes got a pass: survey archaeology did not rip open places that had lain in peace for centuries. Still, sometimes even looking was unseemly. I was part of a suspect crowd.

I had been vaguely aware of the newly passed Native American Graves and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, when I landed in Durango. I knew that it instructed governments and museums to return human remains to their most likely descendants. As a diligent history student, I knew that it was justified. Early archaeology, especially, was little more than a goody grab, with so-called antiquities experts hauling off treasures with little attempt to document or record. I assumed that modern archaeology was different. I thought the impulse to investigate was a mark of respect and that the work we were doing for the Forest Service—finding and documenting cultural sites before they got leveled by a grader or uprooted by a felled tree—would be in line with what Native Americans wanted for their ancestral remains.

So the accusations came as a bit of a shock. So did the response of many archaeologists, which I was only just hearing: they hated NAGPRA. They thought it would, in the words of Jane Buikstra, one of my classroom archaeology heroes, “threaten the future of American archaeology.”

Did my interest in archaeology make me a monster?

All summer, that tension crackled through the office. Sharon’s boss, my Grandboss, was a wry and weathered man with aviator glasses and an enormous belt buckle. He had worked in the Durango area for decades and spoke of NAGPRA with elegant contempt. The American people have spoken, he said. They have decided that this is what they want, so, as an employee of the taxpayers, I must comply.

The interns discussed the issue among ourselves. Grandboss was an ass, we agreed. Obviously NAGPRA was the right thing to do. If it destroyed archaeology as we knew it—well, so what? It was clearly wrong to cling to the oppressive ways of the past. Still: where did that leave us?

As I paced out my survey transects beneath the ponderosa pines, I reflected on the other archaeologists I knew. There was the professor who taught my archaeology classes. He had done some work on the ancient Southwest, but the research he used to apply for tenure was in something else. The defection had confused me, but now it was beginning to make sense.

Then there was Sharon. She was only a few years older than we were, but she had a master’s degree and an infectious laugh that broke out whenever she was dealing with the absurdities of the Forest Service. She had just finished a thesis tracking the source of pine beams used in twelfth-century Pueblo buildings.

She was clearly a brain, and yet I couldn’t figure her out. She smiled when Grandboss started talking about his archaeological exploits: As I rappelled down the cliff toward the site, I thought to myself they must have been scared to death to live all the way up here. And: Back in the seventies we used to be able to do REAL excavations. And: We drank them under the table. But her smile made it clear this was not her kind of archaeology.

She was just as polite but much more firm when he suggested that the Forest Service just take a little tiny sample of bone from an ancestral Pueblo burial found by some members of the public. She had been put in charge of locating possible descendants in accordance with NAGPRA and was busy assembling a list of potential contacts.

He leaned over her cubicle, stroking the handle of his coffee mug with his thumb. What a shame it was, he said, that we had to waste this excellent opportunity for study. The descendants wouldn’t even miss the sample—think of what could be learned!

Sharon levelly repeated the principles of NAGPRA.

I could see that she was at the mercy of both Grandboss and the bureaucracy; her job involved only a small amount of brain. She mostly functioned, it appeared to me, as a kind of recording device, summarizing our findings and writing up reports and recommendations.

As I watched her, I wondered if it was better to just do something else.

“Leave the dead alone.”

—Five Sandoval Pueblo Council, 1997.

After Earl Morris packed up his excavation tents, the rock shelters became little more than a neglected local attraction. Zeke Flora gradually alienated every archaeologist in the four-state area. Helen Daniels fought in vain to house the Falls Creek objects in the Durango Museum. Other researchers occasionally did work at the site, but the best stuff was gone.

Meanwhile, the community in the valley below turned in its sleep, stretched, and started to grow. The economy of Durango shifted from agriculture to tourism; by the early nineties, waitresses and ski bums were getting rich off the proceeds of the real estate they bought in the bust years.

The picturesque ranch below the rock shelters was a logical target for development. It was beautiful and tranquil, and downtown Durango was only six miles away. In 1992, a luxury development that would have gated off the valley was prevented from breaking ground by a coalition of conservationists, the local archaeological society, and the Forest Service, which agreed to purchase five hundred acres directly below the site. That was what we’d been doing, that first week on the job—surveying the acquisition. As soon as we finished, the brains of the San Juan National Forest got to work.

My old Grandboss and the district ranger had a new proposition. Sharon later described their vision to me: “We were gonna excavate! Do interpretation! Have golf carts bring people up to the rock shelter!” It was going to be Grandboss’s crowning glory. The project was hurriedly approved, without consulting any Native Americans.

But before it could be implemented, the political winds shifted. The new Democratic administration replaced the Forest Service Chief, and Grandboss, the district ranger, and the San Juan National Forest supervisor all retired. And in 1994 Sharon, bothered by the project’s failure to comply with NAGPRA, approached her new boss with a suggestion: Since no Native Americans had seen or approved Grandboss’s plan to further excavate, widen the trail, and interpret the site, they should revisit the decision to develop the Falls Creek Archaeological Area.

Her new boss agreed. Furthermore, he decided, they would document their process as they went—no one was really sure how to do effective NAGPRA consultation. As they crafted their report of the decision, they would make a road map and a set of guidelines.

In 1995, the San Juan National Forest contracted with Shirley Powell, an archaeologist who was known for her respectful and collaborative work with tribes. She and Sharon started cold-calling the twenty-six Indian nations and Pueblos that might have a tie to the rock shelters. It was difficult work. The men and women they talked to were skeptical of the archaeologists’ motives and many declined to participate at first. Others agreed, but wondered aloud if they were wasting their time.

One thing emerged quite quickly, however, as Sharon told me later: “They all were against doing anything. All of the burials at the rock shelter made it much too sensitive, too sacred of an area for the Disneyland experience.” Almost universally, they wanted the site to be closed to visitors.

This was when something in Sharon started to shift. She had always believed in the fundamental premise of archaeology, and she wanted to make sure that it was respectfully done. But now she started to doubt that was possible.

She had thought the scientists and the tribes would be working together to understand the past. But it became clear that the archaeological approach she was trained in not only failed to take into account the Indians’ tradition and knowledge, but it also did not get anywhere near what they wanted to know about their ancestors.

“I don’t understand why you’re here,” said a Navajo tribal representative when Sharon went to a council chapter meeting to ask for support on the Falls Creek site development. “We feel very strongly about the protection of graves and not disturbing them. So what you’re asking doesn’t make sense.”

William Weahkee, the executive director of the Five Sandoval Pueblos, was even more direct. “Treat the sites and other sacred places with respect…They’re not a picnic area or carnival. If you can get this through to your people, we’d appreciate it.”

“We had a bad message,” Sharon said. The law of the land was NAGPRA, with which the Forest Service had not even minimally complied when they drafted their plans for Falls Creek. Worse, even on the projects where they did adhere to NAGPRA—like the ancestral Pueblo burial that had been uncovered during my internship—consultation with tribes was treated as just another box to check, rather than a vital step in the process. Sharon and Shirley had to start each conversation with tribal representatives by admitting that the agency considered Indigenous spiritual concerns mostly as an inconvenience.

But as they spoke to more and more tribes, Sharon started to enjoy the process. It felt like they were pioneering a new kind of partnership. The new forest supervisor even had what Sharon describes as a “visible epiphany” when she and Shirley explained the Falls Creek situation: With wonder, he noted that the agency was harder on cases of timber theft than it was on the theft and desecration of sacred sites.

“People must be ‘weaned’ from the idea that they have the right to visit places like the Falls Creek Rock Shelters whenever they so desire.”

— Mr. Leigh Jenkins, Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, 1997.

When I returned to college in the fall of 1992, I changed my major to biology. The following summer, despite an offer from Grandboss to return to the San Juan National Forest as a paid archaeologist, I took an unpaid internship on a Bureau of Land Management wildlife crew.

Even as I left archaeology, I continued for decades to participate in the tourism that is the standard American experience of sacred Native landscapes. After I had kids of my own, I took my family to Mesa Verde; I lingered in the Native American hall at the museum; I leaned in close to read the interpretive signs about religious artifacts. I thought I knew where I stood: firmly anti-exploitation. Yet there was no headline that drew me faster than one promising the prurient details of the latest big archaeological find, such as the discovery and subsequent DNA analysis of the Kennewick man in 1996.

I stayed in this sideways state for decades. Then, in the course of writing an essay on ecotourism in Australia, I read about how the Euro-American scientific method was intimately connected to environmental destruction: How, for example, our understanding of the biology of the duck-billed platypus was attained through the slaughter of hundreds of egg-laying females.

For the first time in years, I thought about Falls Creek. White archaeologists’ understanding of that place, too, had come from destruction. I had always thought knowledge for its own sake was an endless good; while I was vaguely disappointed that I hadn’t gotten the chance to see the rock shelter pithouses before they were destroyed, I hadn’t questioned the impulse to excavate.

It was 2018; twenty-five years had passed since the passage of NAGPRA. I wondered: In a quarter century of archaeologists being compelled to listen to indigenous voices, what had archaeology become?

In search of an answer, I looked up Sharon. I learned that after her marriage (she was now Sharon Milholland) she had gone on to pursue a PhD—but not in archaeology. She’d gotten her doctorate in American Indian studies, and now made her living as a consultant working on behalf of Indian tribes, and with archaeologists wanting to do more sensitive work.

I drove to the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez to meet with her. She told me about some of the work she was doing for the center: Her goal was to go beyond archaeology as usual, to nurture projects that specifically addressed the needs and values of tribal nations. “Archaeology needs to become relevant to Indigenous Peoples,” she said.

She introduced me to her colleague Dan Simplicio, a Zuni, whom she had met while working on the Falls Creek site. They became good friends while brainstorming how to improve on the original Forest Service plan for Falls Creek. “That was when I became born-again culturally sensitive,” she said, laughing but serious. “Dan changed my life.”

She explained how the experience of talking to all twenty-six Indian Nations and Pueblos related to Falls Creek made it clear to her that archaeology had to change. “I learned that I had to appreciate the seriousness of what they were telling me,” she said. “And take action.”

I began to see that I had my dichotomy wrong: Archaeology wasn’t a choice between being an eye and being a brain. Done properly, archaeology involves something more—the heart, maybe. Or the soul.

“Burials are not appropriate to interpret.”

— New Mexico Indian Tourism Association, 1996

The thing Sharon noticed in 1995, as she began to contact Indian Nations and bring tribal members out to visit the site, was that none of them cared about the things she and her colleagues were asking them. Should the parking lot be paved or gravel? Should the interpretive sign talk about the specific history of the site or stay general? Should a fence be barbed wire or chain link? Nobody seemed particularly invested.

Instead, the people they met with were concerned with the state of their ancestors’ spirits. They wanted to know where the human remains had gone, and when they could be returned to their proper resting place. They debated among themselves whether this was even possible; tradition said that reburial should occur as close as possible to the original site, but this site was dangerously accessible and had a history of vandalism. Perhaps it would be better to rebury in a place with better security, like Mesa Verde or a reservation. Only that didn’t really make sense either; the homeland of these spirits was here. They needed to be at the rock shelters, and the rock shelters needed them.

Gravel on the parking lot? Sure, whatever. If parking had to be allowed at all.

The Forest Service hadn’t had anything to do with either the looting or the excavation, and didn’t possess any of the materials that had been taken from the shelters. That didn’t matter, their Native collaborators said. As representatives of the culture responsible for the looting, they needed to help repatriate the stolen grave goods. In fact, until the Forest Service located the remains and reached a consensus about what to do with them, any discussion of the management of the rock shelter was irrelevant.

Sharon saw that there was a fundamental clash of world views: it wasn’t so much that the Forest Service should be following these rules instead of those rules. It was more that the very basis of action was different. She tried to convey this in the government report: she and Shirley wrote that Euro-American explanations of the archaeology of Falls Creek relied on “linear concepts of time and causality,” and that this approach was too limited to serve as the basis for effective management of lands that were sacred to other cultures. They recommended that the shelters be closed to public access and the remains tracked down; her new boss supported the move even though it was likely to be unpopular. “The time was right to set the San Juan National Forest on a new path,” Sharon told me. She pointed out that this did not come about voluntarily: “It took NAGPRA and the strong arm of the law to make managers and archaeologists acknowledge that this was a human rights issue.”

The project changed how she felt about archaeology, too; she realized that she had a responsibility to understand and work with the people whose ancestors had created the cultural remains she was trained to investigate. In 2000, she resigned from the Forest Service to pursue her PhD. If she was going to practice archaeology, she wanted to change it from the inside.

“Archaeology is a misunderstanding, a misappropriation, and it’s still going in the wrong direction. It’s still not being taught. I see younger people, that were interns here at Crow Canyon, come back, and fall right into that pit trap. There’s a real lack of understanding of our perspective.”

– Dan Simplicio, Zuni, 2018

In 2018, after meeting with Sharon and Dan, I paid a visit to the Falls Creek Archaeological Area. The valley is mostly the same as it was in 1992: the fencing around the old pasture has been taken down, and community paths thread back and forth through the grass. It is still startlingly beautiful. I walked along the paths, trying to align the valley in my memory with the one before my eyes. I found myself scanning hopefully for lithic flakes or pottery shards.

Eventually, the Forest Service followed Sharon’s recommendation and closed the Falls Creek Rock Shelters to public access; recreational use was rerouted to the far side of the valley. Parking has been kept minimal and the lone interpretive sign talks about the Basketmaker culture only in general terms, with no mention of the rock shelters or the mummies. It is a tranquil spot—although, as Sharon notes, getting to that tranquility involved a war, one which is still being waged around the globe.

As some predicted, there was an outcry when local archaeology enthusiasts were cut off “cold turkey” from accessing the site. Sharon and her colleagues were accused of succumbing to political correctness, and of favoring “generic Native American values” over the interests of (white) people who now lived near the shelters. But the opposition eventually died down. By 2011, after the Falls Creek human remains and grave goods were finally collected, catalogued, and prepared for repatriation to the Pueblos, the audience at the public hearing for the transfer showed nothing but respect.

If the bones have been reburied, they have now resumed their journey to the other side, crumbling back into the fabric of the earth. This sacred space will continue to anchor the history of the Pueblo people, as well as that of the Ute and the Navajo. It will be known and used in ways most of us are not privy to. Meanwhile, the soil layer in which the looting and the partial restoration took place will eventually silt over. Someone else’s era will begin.

Dan Simplicio had suggested during his consultation with the Forest Service that the site be fenced but otherwise left unmarked—a No Trespassing sign would only spur people’s curiosity, he thought. “Let the trail grow over,” he said. “Keep the vegetation screen in front of the shelters. We want to see it managed like it is not there.”

As I stood there, I shaded my eyes to peer at the dents beneath the cliffs. Pinyons and juniper screened the openings of the rock shelters and from the valley the spaces did not look particularly alluring. The trail that once led to the shelters had disappeared. This trophy, this local jewel in the crown of the US government’s archaeological possessions, had faded almost out of sight. And that was a victory.