Tonight, in Ukraine, children will get on the ground and scrunch themselves up into little balls, trying to make themselves smaller.

In bunkers,

in the backs of cars,

on trains.

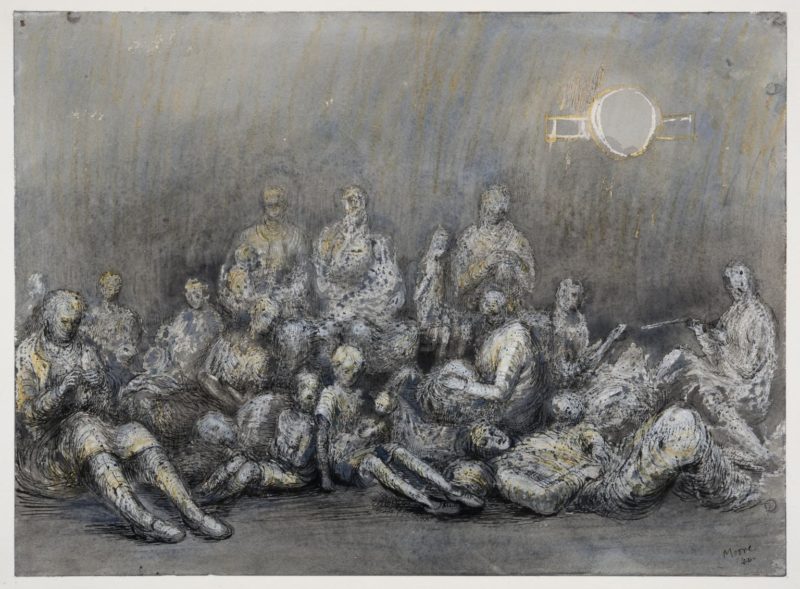

I imagine their small arms tight around their knees. I imagine that in this pose, they look exactly like the Iraqi children who hid under tables at that wedding while American drones rained bombs on them. I imagine they look like the crumpled little squares of Kleenex on my desk.

I think of their friends in Syria, Afghanistan, on the West Bank and in Gaza.

I think of them all: their little backs curled outwards, heads down, trying to survive grown men’s wars.

When I was a young woman, I traveled to Bukavu, and there I met children who must have hunched over like that too as they tried to avoid militia. They were in a safe house near Panzi Hospital, and I was visiting to “inspect” projects. I smiled at them and they smiled back and I felt good. They did not seem afraid to me, but the woman who made medical appointments for their mothers to get sewn back up told me many of them refused to leave their mothers’ sides, not even for a few minutes at a time.

There is a thread tying them together — those kids who made it out of the bush and across the line to Panzi, and the ones before in Bosnia and Rwanda who didn’t. They are connected to the ones in Kyiv, sniffling in cold bunkers, remembering homework assignments from last week, before the war.

Apparently, our views on the war in Ukraine should be determined by our preexisting politics.

Apparently, “Zelenskyy’s hot” and “Putin’s an anti-imperialist hero.”

Apparently, “this is all NATO’s fault.”

Apparently, “Ukrainians and Russians are all racist anyway, so why should we care?”

This is a tragedy in many acts and so,

there are no takes that can make it make sense.

And, like all tragedies, it reveals itself to outsiders in catastrophe.

You can endure punches every night for years, but they only call it a tragedy when he

shoots you dead.

By the time the satellite images beamed on BBC, it was already too late.

By the time the takes started rolling in, the children were already in bunkers,

in the backs of cars,

on trains.

Tonight in Ukraine, children will get on the ground and hunch into little balls, trying to make themselves smaller,

in bunkers,

in the backs of cars,

on trains.

Scrunched little squares of Kleenex.

I think of their friends around the world, the ones who lived before but died, and the ones still holding on now. I think of them all: their little backs curled outwards, heads down, trying to save themselves.

I think of all the children who have been told to make themselves smaller so that they might live.