On Saturday June 9, 2012, Major Avtar Singh, formerly of the Indian Army and living in Selma, California, shot his wife and three children. Before turning the gun on himself, he called the Sheriff’s office and told them that he had killed four people. The SWAT team that responded to the call found his youngest and oldest sons, ages three and seventeen, and his wife, dead of gunshot wounds to the head; the middle son, fifteen years old, was critically injured, but alive. He died a few days later, from wounds to the head.

The execution-style gunshots to the head were identical to those which killed Major Singh’s most famous victim, the Kashmiri human rights lawyer Jalil Andrabi. Andrabi was abducted, tortured and murdered in 1996 for exposing abuses carried out by the Indian Army in Kashmir. Major Avtar Singh was also wanted by Kashmir’s courts and Interpol for the murder of twenty-eight people in Kashmir in the course of his career as an officer in 35 Rashtriya Rifles, a counterinsurgency unit of the Indian Army. The story of his crimes and the manner in which he evaded justice for sixteen years is a grim chronicle of Indian crimes against humanity in Kashmir and of the silence of the international community which has abetted these. The impunity exploited by India and enabled by the international community clearly corrupted Singh’s conscience, to judge by the murder of his family and his subsequent suicide. Until it deals with the gross human rights violations in Kashmir and an impunity that harkens back to its colonial past, India’s proud claims as the world’s most populous democracy are fatally tainted.

The Death of a Lawyer

Jalil Andrabi was a Kashmiri human rights lawyer who dared to challenge the army in the early 1990s as Indian forces fought a pro-independence insurgency. Indian counterinsurgency in Kashmir unfolded as a classic dirty war, where the army regarded the civilian population as the enemy. Widespread abuses by the armed forces—extrajudicial killings, torture, rape, disappearances, firing on unarmed protestors, arson, looting, destruction of houses and crops—were intended to break down popular support for independence. Andrabi founded the Kashmir Commission of Jurists to uphold basic human rights through legal action, and filed thousands of habeas corpus petitions on behalf of detained Kashmiris. Representing prisoners in court, Andrabi won rulings to prevent the army from carrying out torture and extrajudicial executions, or from transferring Kashmiri prisoners to jails outside the state where they would be cut off from family and legal support. He was also outspokenly committed to Kashmiri independence. Before organizations like Human Rights Watch, the International Commission of Jurists, and Amnesty International, he meticulously detailed a saga of official abuse, and was, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “a frequent caller at diplomatic missions in New Delhi, the U.N. Human Rights Commission, and the U.S. State Department.” In 1995, he traveled to Geneva to address the UN Human Rights Commission; he was due to do so again in 1996. In a speech in Delhi a few weeks before his murder in February that year, he describes the situation in Kashmir: “The enormity and the level of atrocities being committed on the people of Kashmir for the last more than six years [sic]” he said, “has been such that it amounts to the abuse of sovereignty… According to some estimates more than 40,000 people have been killed, which include all—old, men and children, women, sick and infirm. The youth of Kashmir have been mowed down. They are tortured in torture cells and… thousands of youth have been killed in police custody. These atrocities being committed on the people of Kashmir are not mere aberrations. These are part of deliberate and systematic state policy… aimed to silence the people of Kashmir into subjugation.”

Andrabi went on to describe the absolute powers given to the Indian military by laws like the Armed Forces (J&K) Special Powers Act (AFSPA) and J&K Disturbed Areas Act. Based directly on colonial legislation used by the British to suppress the Indian movement for independence, these laws gave the armed forces a summary power to shoot to kill—with impunity from prosecution—those accused of human rights violations. The AFSPA, copied from the Armed Forces Special Powers Ordinance of 1942, was adopted by the Indian parliament in 1958. It was promulgated first in Nagaland in the northeast. Like Kashmir, Nagaland was inhabited by ethnic and religious minorities campaigning for independence after the British left the subcontinent. Again like Kashmir, the Indian response to Naga lobbying for self-determination was itself copied directly from colonial models of British counterinsurgency in Malaya, Burma, and Palestine.

[Andrabi] ended with a quote from Human Rights Watch that would make the impunity starkly clear: “The government of India has never made public any action it has taken to investigate these killings and prosecute those responsible.”

In a picture his brother Arshad had blown up for showing to the media, Andrabi has thick eyebrows that arch above sympathetic, slightly mournful eyes. His gaze reads as stubborn, unflagging. Dressed in a gray suit with wide lapels and a slate gray v-neck sweater, he wears a beard that is tightly shaved along with hair moderately trimmed. Anything but effusive, he stares directly at the camera, his mouth almost taciturn, his brow tentative, furrowed. Given the community he worked within, Andrabi witnessed his own friends and colleagues—lawyers and journalists committed to ending the abuses—under constant attack. Arundhati Roy has called Kashmir “the most highly militarized zone in the world.” In April 1995, two unidentified gunmen opened fire on Mian Abdul Qayoom, President of the J&K Bar Association, leaving him seriously injured. In October, High Court Advocate A.Q. Sailani was killed by “unidentified gunmen” a few yards from an army bunker in Srinagar. In his own final public speech, Andrabi memorialized them and others, invoking their names, the dates they were taken. Describing in detail the shots fired, the extrajudicial killings, the disappearances, often the last breaths of these friends, which family members saw them and where, he ended with a quote from Human Rights Watch that would make the impunity starkly clear: “The government of India has never made public any action it has taken to investigate these killings and prosecute those responsible.”

The killing of Jalil Andrabi was staged as a public spectacle. For three days, the neighborhood of Peer Bagh was surrounded by military vehicles and cordoned off; anyone entering or leaving was stopped and questioned. Andrabi’s brothers, who resemble him closely, were stopped this way. On March 8, 1996, the car in which Andrabi and his wife, Rifat, were traveling was waved to stop, and he was taken by soldiers. Rifat pleaded with the head officer to release her husband, but he refused. She could not drive, so, as the convoy sped off, she found an auto-rickshaw (a makeshift motor scooter with passenger seats and an awning, the staple of public transport in the subcontinent) to follow them. The trucks were much faster than the auto; she could not keep up with the convoy.

The same evening Rifat attempted to file a First Incident Report (FIR) naming the army personnel responsible for the abduction at the local police station in Sadar, but she was refused. An Amnesty International report records interference from the police, army, and central government to keep the army from being mentioned in connection with the abduction: “The Inspector General of Police reportedly reassured Rifat Andrabi on the phone later at night that Andrabi was ‘with them’ and would be released after the completion of investigations. On the following morning, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court Bar Association, of which Andrabi was a member, filed a habeas corpus petition in the High Court, which then directed all the law enforcement agencies in the state to declare whether they were holding Andrabi. In a sworn affidavit presented on 11 March, the army stated before the High Court that ‘Rashtriya Rifles do not operate in the said area, neither was any member deputed/present at Parayapora at 5:30 p.m. nor did any member of Rashtriya Rifles apprehend or receive the alleged detinue on the date and time given.’” The Amnesty report indicates that police “urged the family to alter their FIR so as not to mention suspected army involvement but to declare instead that Andrabi had been taken away by unknown persons.” Rifat and her family reluctantly agreed as they were apparently told that if they did so, they could meet Andrabi. “On 13 March,” the report continues, “the FIR was finally registered but the family was not informed of Andrabi’s whereabouts.” As the report makes clear, the High Court was unable to enforce the habeas petition to compel the army and police to produce Andrabi in court. The writ of habeas corpus has been the foundation for the protection of individual liberty and rights from arbitrary state action; effectively, it does not apply in Kashmir. Ten years after the murder of Andrabi, Human Rights Watch cites Kashmiri human rights activists who estimate that there are 60,000 pending habeas petitions in Indian-administered Kashmir.

Given the deep mythic significance of India’s rivers in the Hindu tradition, this defilement is especially telling. ‘The largest democracy in the world’ has polluted its sacred waters with the bodies of its tortured citizens,” said Mahmood.

Weeks later, on March 27th, Andrabi’s body was found in the mud on the banks of the Jhelum, the river that runs through Srinagar. The post-mortem report records evidence of torture: wounds to the head and body, facial bones broken, eyes torn out, skin all over the body loose and peeling, gunshot wounds to the head which finally caused death. Dumping bodies into rivers is a favored method used by the armed forces to dispose of those who die under torture. Srinagar residents who live near the Jhelum are accustomed to finding bodies and body parts in the river and on its banks. Cynthia Mahmood, an anthropologist at the University of Notre Dame has witnessed and experienced the practice of state terror and the violent silencing of dissent. Mahmood is not Indian, but was attacked and gang-raped in India for writing about abuses against the Sikhs in the 1980s, in the course of counterinsurgency operations. She recounts: “In Muzaffarabad, on the Pakistani or ‘free’ side of Kashmir, a blackboard by the banks of the Jhelum River keeps count as Kashmiri bodies float down from across the borders. (When I visited in January 1997, the grim chalk tally then was at 476). Given the deep mythic significance of India’s rivers in the Hindu tradition, this defilement is especially telling. ‘The largest democracy in the world’ has polluted its sacred waters with the bodies of its tortured citizens.”

Andrabi was one of the leading citizens of Srinagar, and his killing was meant as a warning that no one was safe from the army. Protests in Kashmir against the killing, led by Andrabi’s colleagues at the Srinagar High Court Bar Association, and international outrage resulted in an investigation. The High Court ordered the creation of a police Special Investigation Team (SIT). The team’s report identified Major Singh of the 35 Rashtriya Rifles as perpetrator. The Court’s proceedings over the next eleven years record its futile attempts to force the police or the army to produce Major Singh in court to stand trial for Andrabi’s and twenty-eight others’ murders while he was posted in Kashmir in the early- to mid-1990s. The Court went so far as to hold the members of the SIT in contempt for failing to bring Singh to trial, thereby flouting the law and fostering impunity. The army’s response to repeated requests from the High Court was to claim that it was unaware of his whereabouts, that he had acted in an individual capacity, or that he was “absconding.”

While the army, which continued to pay his pension, claimed that it was unable to find Major Singh, a reporter for The Indian Express was able to track him down in Ludhiana in 1998 and interview him. In the interview, which has been discussed but never publicly published, Singh claimed he was being made a scapegoat by the government. In 2004, the army informed the Court that it intended to court-martial Singh, rather than produce him in court to answer the charges against him. The court-martial never happened. The High Court had ordered the government and police in 1997 to impound Singh’s passport and watch all airports, ports, and railway stations to prevent him from leaving the country. In 2006, however, he was discovered to have fled to Canada, seeking asylum there on the grounds that the Indian government was trying to frame him for the murder. The Canadian government asked Interpol for information regarding the murder charges against him, and this request was relayed by way of local police to the court at Budgam.

Groups like the Canadian Center for International Justice and Amnesty International tried to persuade the Canadian government to fulfill its legal obligations as a member of the International Criminal Court to try Singh for crimes against humanity. Despite a thorough investigation in 2007 by the War Crimes Unit of the Canadian Department of Justice, no prosecution was initiated. Singh’s asylum application was denied, and that was deemed by Canadian officials to be sufficient punishment, as it ensured that he would not be able to apply for immigration status in any other country where he might choose to settle. It was doubtless with a sense of relief that the Canadian government found that some time in 2006-7, Singh had illegally entered the United States.

The Nightingale

But Singh’s presence in Canada would spur two important events. First, the legal documents from the case were scrutinized by international human rights lawyers, who became familiar with his modus operandi—that is, of using pro-government militants to carry out a campaign of kidnapping, extortion, torture, and murder. These militants, known as renegades, were recruited from among surrendered militants, trained, armed, paid, and protected by the army. They operated alongside special counterinsurgency forces like the Rashtriya Rifles to terrorize the civilian population and silence critics. According to the statements gathered by the SIT, the manner and reasons for the killing were varied; some of the victims were abducted and tortured to death, others were hanged by Major Singh himself, their bodies left lying along the National Highway with the intention of blaming the crime on armed, pro-independence militants. The reasons for the killings were also varied—extortion, personal animosities, settling family scores, random terror. With his signature ruthlessness, Singh perfected a strategy of disposing of evidence and effectively silencing witnesses, by killing in turn the renegades who had carried out the murders he ordered. One of the statements recorded by the SIT recounts a conversation between Major Singh and a renegade who managed to survive this killing spree: “At my insistance [T] (name withheld) had asked Major Avtar Singh why he killed Sikandar, [who] was working with [the] army. Major Avtar Singh replied that Sikandar and his associates know our secrets. Therefore we cannot trust them. In case he [is] caught by police, he will tell everything about us and will expose the army. Therefore it was better to kill them.” This deadly domino effect brought the known number of Major Singh’s victims to at least twenty-eight. Journalists who knew of him at the time described him as “a tyrant” and “drunk with power.” His colleagues nicknamed him Bulbul, “The Nightingale.”

Journalist Umar Sultan traced Avtar Singh’s other crimes: “Residents of the neighborhood of Batamaloo in downtown Srinagar remember Major Singh taking away scores of youths who were killed in various ways: ‘Our hands were tied from behind. The Major ordered his troops to throw the boy into the Jhelum and they did,’ says Junaid, one of Singh’s would-be victims. ‘I closed my eyes and started praying thinking I would be the next but I was brought back. I feared that nobody would know about my fate.’ Junaid recalls the time when he was held in a Palhalan camp in 1997, and Singh brought a local teacher over. ‘The Major tore his undershirt, bundled it and shoved it in the teacher’s throat with his cane,’ Junaid says. ‘The teacher died in front of my eyes.’ Junaid was later transferred to the Shariefabad army camp, on the outskirts of Srinagar. Major Singh would show up there too, this time bringing Junaid’s neighbors, Mohammad Shaban and his son Yahya Khan of Batamaloo, to the camp.”

“‘Yahya was already dead when he was brought to the camp, his father was tortured to death subsequently,’ recalls Junaid, who was released from Shariefabad two and a half months later. His memory of what he came across inside the garrison is chilling. ‘The Major was notorious for burning people alive in an iron tank inside the Shariefabad camp,’ he says.”

A second consequence of Singh’s presence in Canada was a showdown with India that Canada would lose. Starting some time in late 2007 or early 2008, Canadian immigration authorities began denying visas to Indian military and paramilitary personnel who had been involved in counterinsurgency operations in Kashmir. When this news hit the Indian media in 2010, the Indian government’s response was bullish, demanding that the Canadian government respect Indian sensitivities on Kashmir. In the run-up to the Indian prime minister’s visit to Canada for the G20 summit in May 2010, the Indian government issued a clear ultimatum: Canada could not afford to offend India, in the middle of a global recession. The Canadian Immigration Minister apologized profusely, called the policy a mistake, and promised that it would be discontinued. On immigration blogs, it was predicted that heads would roll; and so, with no discussion of the abuses that led to the visa denials, the first and only international effort to hold Indian military personnel accountable for human rights violations ended ignominiously. Victory for the violators.

Singh had absolute confidence that he would be protected. He even called the local police to complain about harassment when he heard rumors that a Kashmiri journalist had tracked him to his home in Fresno County.

In February 2011, Major Singh again made local headlines in a small town in Fresno County, California. His wife called the police in a domestic violence case, to report that he had tried to choke her. When he was taken into custody, the police found out that he was wanted for murder in Kashmir and that there was an Interpol Red Notice for his arrest. Though living illegally in the US, he owned a thriving trucking business. The Selma Police Chief called the State Department to ask if they should hold Major Singh so that he could be handed over to Interpol, but was told to let him go. His wife did not press charges, and for another year he lived in relative anonymity.

In Kashmir, meanwhile, Jalil Andrabi’s family and the High Court in Budgam continued to pressure the Indian government to extradite Singh to stand trial in India. It was clear to observers following the case that this was in fact the last thing the Indian government wanted; it was also clear to Singh himself, who gave a chillingly candid interview to an Indian journalist in June 2011.

He claimed that he knew who exactly was responsible for the murders, and that the Indian government did not want him in the dock: “There is no question of my being taken to India alive, they will kill me… The agencies, RAW, military intelligence, it is all the same… If the extradition does go through, I will open my mouth, I will not keep quiet.”

“These lives could have been saved if a trial of Major Avtar Singh was conducted on time,” said Andrabi’s brother Arshad. “We have lost that chance now. He was a known murderer and we are appalled that he was even shielded in the United States.”

In this standoff with the Indian government, Singh had absolute confidence that he would be protected. He even called the local police to complain about harassment when he heard rumors that a Kashmiri journalist had tracked him to his home in Fresno County and wanted to interview him. Despite an Interpol notice that he was wanted for murder, he was sure that the local police force would not touch him. In the end, it was not the law, but, apparently, his own haunted conscience that forced a final accounting for his crimes.

The killings in California, if not those in Kashmir, finally forced US media to take notice of the crimes committed by Major Singh. The New York Times, which for the past year had alternated stories of discovery of mass graves in Indian-administered Kashmir with accounts of booming tourism, finally managed to connect the two, conceding that peace can only be based on justice for past killings.

Back in Kashmir, the news of Major Singh’s latest murders and suicide received a subdued response. As Andrabi’s brother Arshad said, Singh’s family’s deaths were due to the Indian government’s refusal to initiate extradition proceedings. “These lives could have been saved if a trial of Major Avtar Singh was conducted on time,” he said. “We have lost that chance now. He was a known murderer and we are appalled that he was even shielded in the United States. It’s a failure of justice at all levels.”

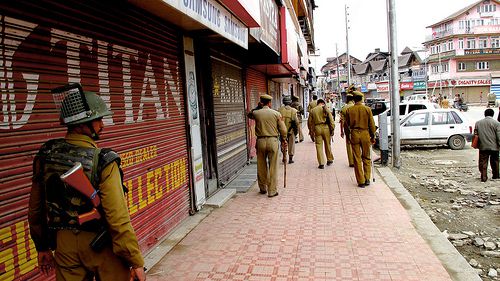

Kashmiris are aware that Major Singh did not act alone. The abuses, torture and killings tellingly continue. As the nature of the revolt against Indian rule changes, returning to its roots as a popular uprising, so do chosen victims of the repression; now they are more likely to be teenagers, boys and young men who grew up knowing only military occupation, who came out into the streets to challenge Indian abuses in the summer of 2010. In the course of this popular uprising, which foreshadowed the Arab Spring, Indian forces killed 122 unarmed protesters, most of them teenagers, the youngest under 10 years old. Since then thousands have been arrested and tortured, many of them young children. They are charged under the Public Safety Act with “waging war against the nation.” Pictures posted on Facebook show these children being beaten and arrested by police and paramilitaries, brought to court and for school examinations in handcuffs and chains. Kashmiris posting on Facebook about the continuing abuses are under constant threat from the army and police.

Matt Eisenbrandt of the Canadian Centre for International Justice is a human rights lawyer who has been among the pioneers in applying the principles of Universal Jurisdiction to bring human rights abusers to justice, no matter where they try to seek shelter: “The Avtar Singh case demonstrates perfectly why we need Universal Jurisdiction to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity and extrajudicial killings in any court around the world and why governments need to exercise that authority. Clearly, the government of India had no interest in bringing Singh to justice for the murder of Jalil Andrabi. But Singh’s presence in Canada and the United States provided opportunities for him to be held accountable in those countries.”

To Eisenbrandt, the failure is clearly systemic and sprawls across borders. “The U.S. government,” he says, “after initially locating and detaining Singh and ordering him deported, took no further steps. Despite being fully aware of Singh’s alleged role in Mr. Andrabi’s murder, the United States took no action. Even after Singh was arrested for domestic violence, nothing was done. At each step along the way, governments had the power to hold Singh accountable but they never did.”

As Jalil Andrabi knew sixteen years ago, these abuses are no aberration. This long chronicle of violence indicates that Indian rule in Kashmir rests on military force and, according to many, has no political legitimacy. The historical and legal grounds for India’s claim to Kashmir are contested by the likes of authors Pankaj Mishra, Arundhati Roy, and Pakistani-British historian Tariq Ali, among many others. In the London Review of Books, Perry Anderson writes that India’s claims to Kashmir are based on “a document, now recently ‘discovered,’ on which the Indian state bases its entire claim to Kashmir, but was unable to produce for over half a century… Still, it remained all too obvious that a province with an overwhelming Muslim majority had been acquired by force and—as would in due course become clear—fraud.” The United Nations recognizes Kashmir as a disputed territory, and maintains military observers on both sides of the Line of Control dividing Indian-held Kashmir from the Pakistani side. In April 2012, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary, or Arbitrary Executions, Christof Heyns, visited Srinagar and met the family of Andrabi; as well as those of five young men who were kidnapped by the army and murdered at Pathribal, then passed off as militants accused of a massacre; he met too with Shakeel Ahangar, whose wife and sister were both raped and murdered, their bodies found in shallow water near one of the army camps surrounding Shopian, and Masooda Parveen, whose husband Ghulam Mohi-ud-din Regoo was detained, tortured and killed by the army in 1998. Heyns’s visit was hosted by the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), a remarkable group which under the leadership of Parveena Ahangar, one of the mothers of the disappeared, has led the way in seeking justice and accountability for human rights abuses in Kashmir.

According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Heyns’s report called upon the Indian government to “take measures to fight impunity in cases of extrajudicial executions, and communal and traditional killings.” Given how far the Indian government has gone to protect criminals like Singh, these words rang empty to many. Kashmiris and a small but growing global constituency concerned with the resolution of the conflict are also aware that the Indian government, which provides legal impunity to its military personnel, cannot be trusted to investigate and prosecute their crimes. In fact, the Indian Supreme Court twice dismissed legal challenges to the Armed Forces Special Powers Act—in 1997 and 2007—arguing that it is an essential element of Indian government in border regions. In light of this, I would argue that it is time for an International Criminal Tribunal on Kashmir, to record and account for twenty-three years of crimes against humanity. It is from this record that a real political solution can emerge.

Shubh Mathur is an Indian anthropologist whose interests include human rights, nations and borders, the death penalty, minorities, immigration and Muslim communities in the United States, gender, South Asia, and the Indian Ocean world. She has conducted fieldwork in India, New York City, and Kashmir. Her first book, The Everyday Life of Hindu Nationalism, was published by the Three Essays Collective press. She is currently working on a collaborative ethnography with the families of the disappeared in Kashmir.