Born and raised in South Korea, artist Hyon Gyon Park left her homeland for Japan. It’s there that she has created the paintings she is famous for: paintings in which mysterious entities, said to represent human emotions, move through what Park calls “an endless cycle of creation and extinction.”

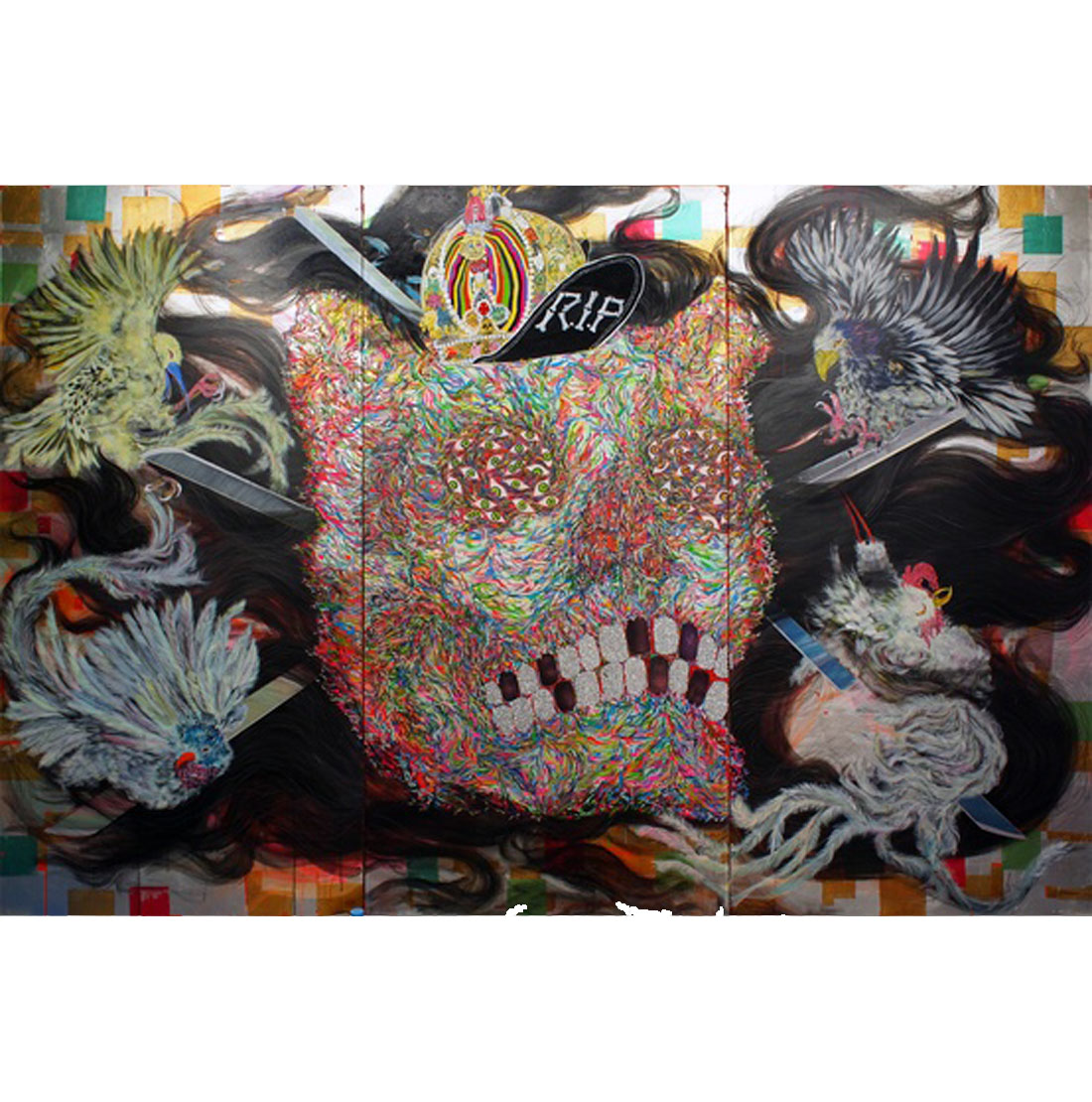

Park’s art is heavily influenced by Korean shamanistic tradition, and this is perhaps most evident in the images she makes out of melted fabric. The colors are bold. Rainbows shoot out from beings she calls “incarnations.” One painting, aptly titled “RIP,” shows a skull surrounded by a mass of dark hair. Interestingly, unruly black hair features prominently in all the paintings that make up her first solo show at New York’s Shin Gallery. She told me the tangled locks represent, among other things, “a desire to free oneself from suppressed pain and societal order.”

Due to time zone conflicts, we conducted the interview by e-mail from D.C. and Kyoto. We wrote in Korean, and I am both interviewer and translator for the text below. (A Korean language version is available here.)

—Sara Yu for Guernica

Guernica: Your exhibit in New York—your first solo in the U.S.—is titled “The Incarnation of the World.” Why?

Hyon Gyon Park: The subjects in my work appear as unidentified ghosts or monsters that can’t be said to be of this world. I’ve decided to call them incarnations. In various religions, myths, and legends, the word “incarnation” refers to the birth or emergence of transcendent beings in the form of humans or other bodies. If “incarnation” denotes the appearance of an abstract being in some concrete form, in a gut ceremony, a shaman could be considered an incarnation of our desires, hopes, and sorrows. The incarnations that appear in my work are always new and I meet them for the first time by drawing them.

Guernica: Your paintings incorporate cloth that is melted down and transformed. How do you settle on the fabric, and why did you choose to use cloth to achieve the multi-colored effect?

Hyon Gyon Park: When I was little, I would play with different colored quilts and cushions in my mother’s closet. My favorite things to play with were shiny embroidered fabrics, which were exciting toys. I would draw on them and burn holes in them with a lighter. I remember noticing that the burning speed was too fast to create any sort of detailed illustration using that method.

I often transcribe my Japanese titles into English and it feels as though I’m creating a password or code.

I had forgotten about that incident until after art school when I started working at a boutique that made hanbok [Korean traditional dress]. Buried in fabric of all hues, I arranged existing colors rather than mixing them to create new colors.

The fabrics I’ve used in my work are satin and sateen. Sateen is very glossy and far from luxurious. Bright solid colors with too much sheen seem gaudy, pathetic and nostalgia-inducing. Such fabrics are reminiscent of the power of chaos in a shaman’s space: overabundant offerings of food on alters, kitschy decorations, provocative shades, vigorous dancing, plaintive singing, absurd fits of crying and laughing, and self-abandonment.

In addition, the striking colors lure you from the ordinary into the extraordinary. Because satin and sateen are composite textiles that melt easily, I used an iron to soften them down to create the images. The process involves repeated melting, burning, and layering, so the resulting work is closer to a sculpture than a painting.

During this repetitive process, faces gradually appear. It’s more accurate to say that they spring out, or arrive.

Guernica: What is the role of the dark, wavy hair that dominates each piece.

Hyon Gyon Park: Not only is hair a part of the body, but because it continues to grow for a time after death, it was considered a symbol of life and spiritual power. Likewise, hair to me is an element of mystery and an intriguing subject that rouses my imagination.

In my work, hair denotes the flow of life prior to being freed from pain. I fill the hair with human struggles such as deep-rooted anxieties, stubborn attachment to life, obsessions, and restrictions. Appearing fluid like a live organism, the hair symbolizes longevity and patience, but when it appears coarse, the hair expresses an energetic life force and freedom. Black hair adds a distinct Asian element. Hair that is shiny and pulled back neatly suggests beauty, while messy or unkempt hair brings to mind a soulless body or corpse. Messy, tangled black hair portends turbulence and represents a desire to free oneself from suppressed pain and societal order. Black does not signify the darkness related to death or nothingness, but a darkness that combines everything and holds the possibility of creation, a temporary death that embraces rebirth.

Guernica: An initial reaction to your work might include fear, awe, confusion, or even anxiety. Some people face difficult emotions with grace and openness, while others suppress them or collapse. What happens in the world of your paintings?

Hyon Gyon Park: Desire and loss of will tend to hurt the mind, which can lead to fear and compulsion. The result is that we suppress negative emotions, which we’ve been taught to be shameful of and hide, such as pain, anger, sorrow, and resentment. I take these complex and varied emotions surrounded by obscurity, absurdity, contradiction, and events out of our control such as tragedy, and project them in my work. So I understand that the images can generate fear, confusion, and anxiety in the audience, and if they’re difficult to turn away from, it only means that my intention has been communicated.

Guernica: Can you explain the Japanese titles of two of your paintings, “Zawazawa Zudodon Shupin Shupin” and “Ningensama”?

Hyon Gyon Park: Zawazawa Zudodon Shupin Shupin is a combination of onomatopoeic words. I don’t think either title can be translated. Sound words can’t be understood through formal study of the language alone. They’re felt when you immerse yourself in the culture or lifestyle that becomes a part of you. The Japanese language is abundant with onomatopoeia. Even though I’ve lived in Japan a long time, sound words are still an uncertain territory. And I think new words are being created every day. Even when I don’t know a word I can sometimes connect it to a meaning using the sensations produced by the sounds, which feels like I’m playing with words.

Zawazawa indicates the sound of something stirring or buzzing, zudodon brings to mind someone running while making noise, and shupin shupin is the sound of a sharp object flying through the air. In this piece, the discord and distress that result from human conflicts and the attempts to overcome them are expressed dynamically. I came up with the title for Zawazawa after finishing the painting, at which point I felt the urge to express the visual just with sound. Ningensama literally means “Mr. (or Ms.) Human.”

Sama, like its Korean equivalent, nim, is a form of address showing respect. It’s a touch of cynicism added to emphasize the message that humans are neither god nor Buddha, but simply human. My English isn’t very good, so for fear of bad translation, I often transcribe my Japanese titles into English and it feels as though I’m creating a password or code.

Guernica: Can you talk about the influence of shamanism on yourself as an artist?

Hyon Gyon Park: Shamanism has a long history and exists to this day because of its ties to universal emotions such as happiness, sorrow, resentment, and love. It can function as an outlet during struggles with life and death and the burdens of society’s absurdities including the divide between rich and poor. It opens up a way to confront reality. Even though shamans have played these roles, they have always been considered lowly and were scorned. Many feel disgust toward the shaman’s role as intermediary between the spirit and physical worlds, their dangerous performances, and their tribal clothing and props. There’s even a movement dedicated to abolishing shamanism, labeling it superstition and barbarism. In the process of modernization, shamanism was considered a negative part of Korean society that many wanted to hide.

Extraordinary acts performed with remarkable exaggeration encounter the human instinct to demolish one’s own limitations, producing catharsis.

Before one becomes a shaman, one goes through a series of trials. Unknown illnesses, nightmares, and violent spasms inflicted upon the chosen individual that get worse each time she rejects her fate. Even after becoming a shaman, she carries this pressure. The extraordinary performances during gut represent the journey of the shaman into a spiritual realm, but I also think that the pain and suffering of everyone gathered at the site gets manifested through the shaman. The nerve-wracking violent performance is a visual expression of the grief and agony in each individual. People do tend to fear and despise shamans but turn to them in times of desperation. Such a contradiction is a human characteristic, no? I’m more pulled to the human drama of shamans—their experience in society and identity struggles—than their transcendental power. Their drastic lives enable them to empathize with others and provide solace.

When my grandmother passed away, I was in Japan and couldn’t attend the funeral. The sadness, guilt, and other conflicting emotions I felt at the time always bothered me and I didn’t know how to release them. On the forty-ninth day after her death, my family called a shaman to perform a gut at our home. It was an unforgettable experience. What I experienced was the process of purification of the negative emotions that accompany human tragedies, a topic I had been consistently interested in. The ritual was an endless cycle of creation and extinction in which everything—sadness, joy, anger, attachment, love, hatred, obsession with life, fear of death, desire, pain—was swallowed up. The experience had a profound effect on me as both an individual and an artist. I felt that I had at last found my subject matter.

Guernica: Do you consider yourself a feminist?

Hyon Gyon Park: The female experience throughout the history of Korea has been accompanied by physical and mental anguish. This negative aspect of Korean history is one of the driving forces behind my work. To imagine transcending time and space to live in the body of another person is not only one of the key elements that shape my work, but also, it is an opportunity to revisit and understand the ways women have long been viewed and treated in Korea. If you are born a female and live as one, you can’t deny your connection to feminism. I think if you are a female, you are a feminist. As far as my work goes, I don’t want it to be interpreted solely from a feminist perspective, of course, but for a woman to have no interest in feminism or say that it doesn’t concern her is self-denial. I know that sexism still exists within various societies and systems, whether blatantly or subtly. We are, however, much better off than previous generations.

Guernica: Korean female shamans have been able to exercise power in a society that has been harsh on women. They can embody an otherworldly strength and are known to dance on top of knives without injuring themselves. Their ecstatic dancing is a cathartic act as well as a performance. The rituals are often intense enough to make spectators tremble in fear or weep. I see this intensity in your paintings, in addition to catharsis in the form of rainbows pouring out from the body. I interpreted it as a visual expression of the spiritual process of a shaman during the ritual of gut. What is the meaning of catharsis in your work?

Hyon Gyon Park: Before she is an individual, a shaman is foremost a vehicle for receiving and expressing the grief and indignation of the people within society. The otherworldly strength that you see during a gut is the raging effort to forget and overcome the weakness of the self and is possible because it bears all the wrath and indignation of the people against oppression. Extraordinary acts performed with remarkable exaggeration encounter the human instinct to demolish one’s own limitations, producing catharsis.

There, all things considered taboo get ripped apart, and one feels the satisfaction of being freed from agony through vituperation and laughter. Hence, shamanism could be said to have developed a means to tackle and override the barriers, oppression, and despair that tend to obstruct life. The irony is that women shamans—mudangs—who belonged to the lower levels of society were in charge of it all. These women of lowest status were able to practice their craft as intermediaries between humans and spirits, purifying people of agony and oppression and intervening in their suffering and tragedies. Art-making is an extension of the kind of spiritual process that shamans unfold in order to demonstrate the connectedness of the world beyond reality.

It’s difficult to define catharsis. But I think that only those who acknowledge and respond to unseen worlds and energies can harness the power of those sources. The catharsis I experienced with my whole body during gut is reflected in my work.

지금 뉴욕에서 미국에서의 첫번째 개인전을 열고 있는데 전시회 주제가 “The

Incarnation of the World,”어떤의미인지?

내 작품속의 인물들은 이 세계의 것이라고 부르기 힘든 정체불명의 유령이나

몬스터들처럼 보인다. 나는 이것들을 화신(化身)이라 부르기로 하겠다. 화신은

종교, 신화, 전설 등에서, 초월적인 존재가 인간 등의 몸으로 탄생하거나

출현하는 것을 말한다. 추상적인 어떤 존재가 구체적인 형태를 빌려 나타나게

되는것이 화신이라고 한다면, 굿판에서 무당은 우리들의 욕망과 희망과

슬픔등을 뒤집어 쓰고 나타난 [화신]이라고 할수 있겠다.

내 작품속에 나타난 정체 불명의 인물들은, 사실 그리는 나도 매번 처음

접하게되는 얼굴이다.

작품들에서 옷감들을 소재로 빈번하게 사용하는 것을 볼수 있는데, 그 중

어떤것은 녹여지고 변형된 옷감들을 사용하는것 볼수있다. 어떤 계기로 이런 천

종류의 소재를 선택하게 됬으며 복잡한 색채를 표현 하는데 사용하게 됬는지?

나는 어릴적에 엄마가 시집올때 가져 왔다는 장롱속에 있던 색색의 철 지난

이불보나 방석 등을 꺼내서 갖고 놀았는데, 광택이 있고 자수가 놓여진 화려한

색의 천들은 정말 흥분되는 장난감 이었다. 그 위에 그림을 그려보기도 하고

라이터로 구멍을 뚫으며 그림을 그려 보려고 시도도 해보곤 하였다, 그때 천이

엄청난 스피드로 타들어가는 것을 알고 깜짝 놀랐었는데 라이터로 섬세한

표현을 하기에는 너무 힘들었던 기억이 있다.

어릴적의 경험은 까맣게 잊고 지내다가, 나는 미술대학에 들어가고, 졸업하고

취직도 했다. 내가 일을 하던 곳은 한복을 중점으로 제작하는 부티크 였는데,

매일 수많은 천들과 수많은 색들에 싸여 일을 했었다. 그때 일을 하면서 물감을

섞어서 색을 만드는거 보다 기존에 있는 색들을 배색 하는것으로 표현하는

트레이닝을 많이 한것 같다.

작품에 쓰여진 천은 공단, 그리고 공단과 비슷한 성질을 가진 사텐이라는

소재이다. 원래 사텐은 희번득거리는 광택을 지닌 고급스러움과는 거리가 먼

소재이기도 하다. 강한 원색과 광택은 서글플 정도로 화려하면서도 왠지모를

노스탤지어를 느끼게 한다. 사텐은, 제단에 쌓아올린 넘치는 음식들, 자아를

잃어버린 난장성, 키치한 장식들 무당의 다이내믹한 움직임과 자극적인 색채,

노래, 도를 넘어선 울음소리, 웃음소리. 이 모든것들이 공존하는 무질서한 공간이

주는 압도적인 에네르기와 많이 닮았다.

그리고 강렬하고 과장스러운 색감은 우리를 일상에서 비일상으로 유도해

준다. 사텐이나 공단을 이용한 작품은 그들이 가진 색뿐 아니라 열에 잘 녹는

성질을 지닌 합성섬유인 것을 이용하여 전기인두로 녹여가며 그리는 방법으로

제작했다. 천을 지지고 태우고 겹치는 행위를 몇번이고 반복하며 만들어 가기

때문에 페인팅 이라기보다는 조각에 가깝다고 할수 있겠다.

녹이고 겹치는 행위를 몇번이고 반복하는 사이에 점점 얼굴같은 형태가 부각을

드러내기 시작한다. 그렸다 라는 표현보다는 튀어 나왔다, 출현했다 라고 하는

표현이 적당 할수도 있겠다.

각각의 작품에서 어두운 톤의 물결무늬 머리카락들이 핵심요소로 표현되고

있는데 작품들에서 이 머리카락들의 역할이 무었인지?

머리카락은 인간의 육체의 일부이기도 하지만 부패하지 않고 사후에도 일정기간

동안 자란다는 그 신비성에 의해 상징이나 기호의 대상으로써 생명력이 씌여진

영력의 장 이라고도 믿어져 왔다고 한다. 머리카락은 나에게도 신비한 영역이고

상상력을 불러일으키는 매력적인 소재이기도 하다.

내 작품에서 머리카락은 고통에서 해방 되기까지의 인생의 일련의 흐름을

나타내고 있다. 인간이 품고 있던 마음속의 응어리, 생에 대한 미련, 집착, 속박.

이 모든 감정들에서 해방 되어지는 순간을 나는 머리카락에 담아서 표현하고

있다. 살아있는 생명체와 같은 머리카락은 질긴 생명력, 인내를 상징하며 거칠게

나부끼는 머리카락은 에네르기 충만한 생명력과 해방을 표현하고 있다. 특히

작품에 나타나는 머리카락은 대부분 검정색으로 표현되고 있다. 흑발은 지극히

동양적이다. 탄탄히 틀어올린 윤기나는 검은머리는 아름답고, 빠져 흐트러진

검은머리는 혼이 빠져버린 사체처럼 보이기도 한다. 헝클어져 흐트러진 흑발은,

파란의 전조를 상상하게 하고, 억눌러왔던 고통, 사회질서로 부터의 탈피를

호소하는 듯한 인상을 준다. 모든것을 흡수하는 듯한 검정은 단지 모든것이 끝난

어둠, 죽음을 의미하는 검정이 아니라 모든것이 혼잡된 어둠, 새로운 창조의

가능성을 품은 에네르기, 재생을 품은 일시적 죽음을 나타내는 색이라고 할수

있다.

작가의 작품들은 처음에 관객들로 하여금 공포, 경외감, 혼돈, 혹은 불안 등의

감정들을 갖게 만드는데 그럼에도 불구하고 작품에서 눈을 뗄수가 없다. 살아

가면서 어떤 사람들은 부정적인 감정들에 직면해도 의연하게 대처하는 반면 어떤

사람들은 그러한 감정들을 억압하고 또 어떤 사람들은 그 감정에 의해 무너지고

만다. 박작가의 작품세상 에서는 어떤 일들이 일어나고 있는가?

인간의 욕구나 의지의 좌절등은 마음속에 상처를 입히고 그로 인해 편집적,

강박적인 감정을 낳게된다. 복잡하게 엉키어 버린 심리상태는 고통, 화, 슬픔,

원망 등 네가티브한 감정등을 동반하며 보기 싫은것, 추한것들로 인식되어

온 이러한 감정들은 밖으로 끄집어 내지도 못한채 안을 향해 억눌려 왔다.

나는 복잡 다양한 인간의 감정、특히 그 중에서도 살아가는 동안 직면하게

되는 불가해한 일들, 부조리, 모순 등으로 부터 발생하는 감정들이나, 인간의

힘으로는 어찌할수없는 문제들, 말하자면 인간의 불행에 관련된 감정에 관심을

갖고 작품에 투영시키고 있다. 그렇기 때문에 나의 작품이 관객들에게 공포,

혼돈, 불안 등의 감정을 갖게 만들수도 있겠다, 그럼에도 불구하고 작품에서

눈을 뗄수 없다는 것은 내가 작품에서 의도한 바가 잘 전달 되었다고 생각한다 .

일본어로 되있는 두 작품의 제목 설명을 부탁 한다면?

Zawazawa Zudodon Shupin shupin & Ningensama

일단 zawazawa zudodon shupin shupin은 의성어를 짜집기하여 붙인 제목이다,

이 두 제목은 한국어나 영어로 표현 불가능 하다고 생각한다. 내가 생각하기에

의성어는 학습으로 습득하는 것이 아니라 그 나라의 언어뿐 아니라 생활 습관,

문화 등이 몸에 배면서 감각적으로 습득 가능하게 된다고 생각한다, 일본어는

의성어가 정말 풍부한 언어이기도 하다. 일본에 오래 살았는데도 불구하고

아직도 의성어는 미지의 세계이다. 그리고 하루가 다르게 또 새로운 의성어가

탄생하고 있다는 느낌도 든다. 그러나 소리나 감각으로 여러가지 의미를

연상시키기 때문에 의미를 몰라도 어느 정도는 통하는 부분도 있고, 언어를 갖고

놀이를 한다는 감각에 가깝다.

자와자와는 뭔가 주변이 술렁술렁 거리는 모습을 나타내는 소리이다,

즈도동은 소리를 내면서 뛰어가는 모습을 연상시키는 소리이고, 슈핑슈핑은

예리한 물건이 날라오는 이미지의 소리이다. 이 작품은 타자와의 관계에서

발생하는 엇갈림, 갈등, 트라우마와 공존 하면서, 그것을 극복하려 하는 모습을

다이내믹하게 표현하고 있다. 자와자와 쥬도동 슈핑슈핑의 작품은 완성을

시키고 타이틀을 정했는데, 작품 안에서 일어나고 있는 모습을 소리만으로

표현해 보고 싶다는 충동으로 정한 제목이다. Ningensama는 한국어로 굳이

표현하자면 인간님.

Sama라는 단어는 이름 뒤에 붙여서 상대방을 높이 세우는 존칭어라고 할수

있겠다. 한국어로 치면 ~님이 되겠다. 이 작품은 힘이 가진 불변의 지배력 앞에

인간은 신도 부처도 아닌 단지 인간일 뿐 이라는 메세지를 포함해 sama라는

단어를 붙임으로써 비아냥을 얹어 표현했다. 영어를 잘 모르는 내가 영어로

타이틀을 번역 했다가는 의미가 잘못 전달 될 수도 있고, 딱 맞는 단어를 선택

하는것도 정말 어려운 일이다. 그럴때는 가끔 표기를 알파벳으로 바꿔 하나의

암호나 기호처럼 만들어 버리기도 한다.

한국의 무속신앙이 작가로서의 본인에게 어떤 영향을 주었는지?

무속신앙이 현대까지 끈질기게 남아오게된 배경에는, 인간의 기쁨, 슬픔, 원망,

사랑같은 보편적 감정과 관련되어 있다. 민중의 입장에 서서 인간의 탄생과

죽음, 빈부의 차, 사회 부조리 등의 문제를 짊어진 사람들의 출구가 되어주고,

현실을 직시 할수 있는 길을 열어주고 있는 것이다. 이러한 역할을 해오면서도

무당은 사회적으로 신분도 낮을 뿐더러 천히 여겨지고 긴 세월 핍박을 받으면서

살아왔다. 영적 중개자 역할을 하거나, 위험을 동반하는 퍼포먼스나 토속적

모습에 혐오감을 느끼는 사람들도 적지 않고 미신타파 라는 슬로건 밑에

야만이다, 미개이다 하는 분위기가 사회에 나타나기 시작하기도 했다. 무속은

한국사회의 발전과정에 있어서 숨기고싶은 [음]의 부분이기도 했던 것이다.

무당은 개인적으로도 시련을 겪을 수밖에 없다, 신에 의해 선택 받은 거역할수

없는 운명을 받아들일 떄까지 원인불명의 병, 꿈, 망각, 발작에 시달리고 심신이

쇠약해 지면서 거부하면 거부 할수록 증상이 심해지는 통과의례를 거치게 된다,

그들은 평생 이러한 가슴속의 응어리를 품고 살아가지 않을수 없다. 굿판에서

보여지는 인간을 초월한 과격한 퍼포먼스는, 무당이 한 인간에서 신의 영역으로

다가갔다는 것의 표시 이기도 하지만, 나는 굿판에 모여든 이들 모두의 아픔을

끌어안고 그것을 시각화 하고 있다는 생각이 든다. 신경을 자극하는 무당의

폭력성을 통해서 개개인 안에 내재해 있는 아픔, 비극 등이 시각화 되고 있는

것이다. 사람들은 자신들과 다른 세계를 살아가는 무당들을 두려워하고 멸시

하면서도 정말 절실한 상황이 되면 기대고 도움을 청하기도 한다. 그러나 이러한

모순또한 인간이 지닌 본성이 아닌가.

나는 무당이 가진 초월적 능력보다 그들이 이 사회 안에서 평생 짊어지고 살면서

겪게되는 모순, 아이덴티티의 혼동, 고통 등 그들의 인간적인 드라마에 더 매력을

느낀다. 그들이 살아온 처절한 인생 드라마가 타인의 아픔을 상상하고 위로

하는것을 가능하게끔 만드는게 아닐까.

나는 할머니가 돌아가셨을때 일본에 있어 장례식에 참석 할수가 없었다. 그

죄책감과 슬픔, 그리고 어디를 향해서 분출 해야할지 모르는 의미불명의

감정들의 충돌이 나를 늘 괴롭혀 왔다. 할머니가 돌아가시고 49제때 우리집에서

무당을 불러 굿을 하게 되었는데 그때의 경험을 잊을수가 없다 . 내가 일관되게

관심을 갖고있던 인간의 불행에 동반하는 네가티브한 감정을 해소, 정화 시키는

과정을 나는 굿에서 발견 할수가 있었다. 슬픔도, 기쁨도, 화도, 정도, 사랑도,

미움도, 증오도, 삶에 대한 집착도, 죽음에 대한 공포도, 갖지 못한것에 대한

욕구도 욕망도, 모든이의 아픔도, 전부 끌어안고 집어 삼키는 굿판에는 생성과

소멸이 끝없이 되풀이 되고 있었다. 이러한 경험은 한 인간으로서의 나뿐 아니라,

작가로서의 나에게 큰 영향을 주었다. 나는 그동안 찾아 헤매왔던 영원한 테마를

그안에서 찾았다는 생각이 든다.

스스로를 페미니스트라 생각하는가?

여성의 경험, 그것에 동반하는 육체적 정신적 고통, 길게 지속되온 한국의

네가티브한 역사의 부분은 내게 작품을 만드는 하나의 원동력 이라고도 할수

있겠다. 여성을 통해, 시공을 초월해 타자로서 살아본다는 것은 내 작품을

형성하는 하나의 요소일 뿐 아니라 내가 태어나 자란 한국이라는 나라의 오랜

세월 스며져 있던 여성에 대한 시선을 재확인 하고 이해를 할수있는 계기가

되고 있다. 여성으로 태어나 여성으로서 살아가는한 페미니즘과의 관계를

부정 할수는 없다. 여성으로 태어난 이상 모두가 페미니스트라고 생각한다.

작품의 폭을 생각한다면, 페미니즘적 관점에서만 해석되어 지는것은 원하는

바가 아니지만, 페미니즘에 관심이 없다던가 스스로와 관련 없다고 말하는 것은

스스로가 여성임을 부정하는 것과 같다고 생각한다. 물론 지금도 성 차별이

국가나 사회 속 여러가지 시스템 안에서 교묘히 감추어져서 아니면 적나라하게,

존재해 오고 있는것은 사실 이라고 생각한다. 하지만 지금의 우리들은 전세대의

여성들처럼 성 차별에 의한 피해나 불편함을 절실히 느끼면서 살고 있지는 않다.

한국은 전통적으로 여자에게 힘을 주어지지 않는 사회였지만 무당이라 불리우는

여자 무속인들은 막강한 파워를 가질수 있었다. 무당들은 영적 세계의 힘을 구현

할수 있어서 칼날 위에서도 다치지 않고 춤을 추기도 한다. 그들의 무아지경에서

추는 춤은 한편의 공연이자 카타르시스를 일으키는 행위이다. 그들의 의식은

때때로 너무 강렬해서 보는 이들을 공포로 떨게 만들거나 눈물을 흘리게도 한다.

박작가의 작품에서도 현실에선 불가능한 강한 힘이 보인다. 몸 안에서 뿜어져

나오는 무지개에서 그러한 카타르시르를 느낄수 있었다. 처음 당신의 작품을

봤을때, 무당이 굿을 하면서 스스로 경험할수 있는 영적 프로세스가 시각적으로

표현됬다고 느꼈다. 작품 안에서 나타나는 카타르시스의 의미가 무엇인지?

무당은 한 개인이기 이전에 사회적 으로는 민중의 원한을 받아들여 상징적으로

표현하는 존재이기도 하다. 굿에서 보여지는 무당의 현실에선 불가능한 힘은,

현실에서의 자신의 약함을 잊고 극복하기 위한 발버둥이며, 우리 모두의 억압에

대한 울분을 짊어지고 있기에 가능하다. 굿에서 보여지는 압도적인 과장함에

의한 비일상성은 자기존재의 한계를 부숴 버리려고 하는 인간의 본능과 만나,

카타르시스를 가져다 준다.

거기에는 현실에서 타부시 되어 온 것들을 갈기갈기 찢어 버리고. 웃음이 섞인

독설을 내뱉게 하고, 고뇌에서 해방 시켜주는 통쾌함이 있다, 이렇게 무속은

인생의 앞을 막아오는 장벽이나 억압, 또는 좌절감에 맞서, 뛰어 넘을수 있는

[기술]을 키워 왔다고 할수 있다. 아이러니한 것은 이 모든걸 주관해 온 것이,

여성이라는 사회적 약자일 뿐 아니라, 천민의 신분이기도한 무당이라는 것이다.

어찌보면 사회의 가장 저변에 위치한 무당이, 인간과 신의 중개자로 살아가면서

민중들의 고통과 억압을 정화시키고. 인간의 불행에 관계하면서 기능 하고 있는

것이다. 그리고 이 부분이 내가 생각하는 아트의 근원적 힘이기도 하다. 현실을

넘어서 연결 되어있는 세계를 보여주기 위해 필사적으로 갈등하는 무당이

펼치는 영적 프로세스와 작품을 만드는 행위는 연장선상에 있다고 생각한다.

카타르시스의 의미를 말로 표현하기는 어렵다, 왜냐하면 카타르시스에 대한

정의는 제각각이고, 검증할수 있는 것이 아니기 때문이다. 그러나 눈에 보이지

않는 세계나 존재, 불가시의 에네르기 등은 그것에 공감하고 느끼는 이들에게만

그 힘을 발휘 한다고 생각한다. 내가 굿을 통해 전신으로 느낀 카타르시스는 나의

몸을 통해 그대로 나의 작품 안에 투영시키고 있다.

Hyon Gyon Park is based in Kyoto, Japan. She received her BA from Mokwon University in Korea and her MA and PhD from Kyoto City University of Arts in Japan. She has exhibited her work internationally in various solo and group exhibitions, including at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Kyoto Art Center, Art Stage Singapore, and g3 Gallery in Tokyo. Her most recent solo exhibition was at the Shin Gallery in New York. She has received numerous grants and fellowships, including the 2012 Kyoto City Special Bounty of Art and Culture.

Sara Yu lives, writes, translates, and teaches in Maryland. In 2012, she received KLTI’s 11th Korean Literature Translation Award for New Translators. She holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

To contact Guernica or Sara Yu, please write here