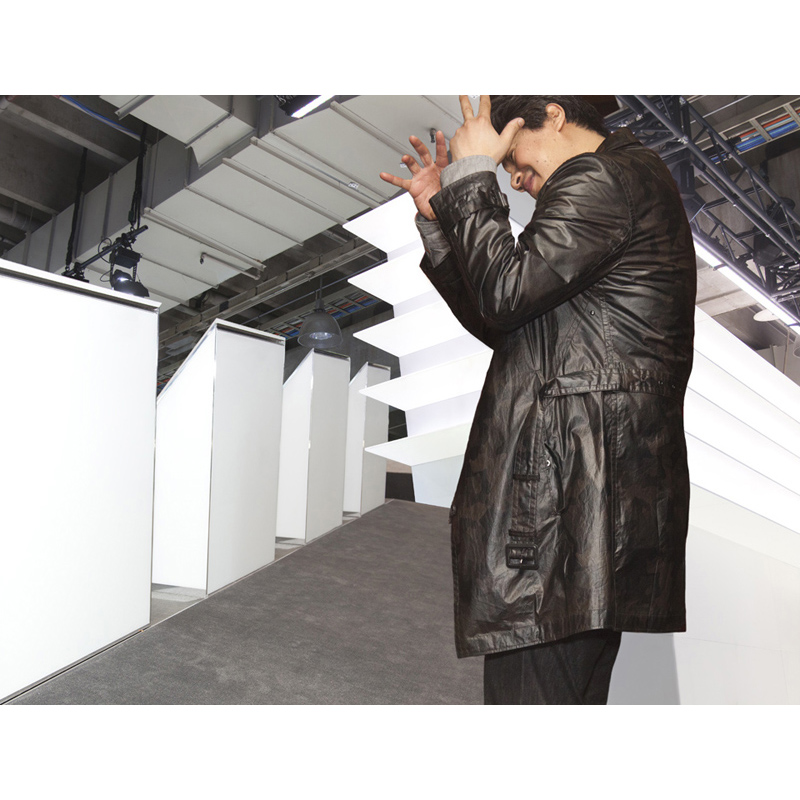

Mónika Sziládi’s work is vibrantly disorienting. Photographing mostly straight, candid images at inorganic events—trade shows, networking and PR affairs—and later creating digital montages, the artist examines the increasingly muddled separation between public and private. Handheld devices appear more often than not, becoming unlikely centerpieces.

Can there be a concrete self? Is social media existentially subtractive? How do we behave when we know we are being watched, when we perform for the camera, for the media, or for our peers? Is it possible for communications culture to legitimize the individual (or individuality)? Can social media authenticate “authenticity”? Is there even such a thing? Is the curated self a present entity? Sziládi intentionally leaves space to explore the indefinite, with surreal humor, a cast of Instagram caricatures, ambiguous situations, and spatially confusing perspectives.

Born and raised in communist Hungary, Sziládi briefly lived in France before moving to New York. She is currently the 2014-2015 artist in residence at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. In July, Sziládi will be featured in Summer Open, the annual exhibition curated by Aperture. Her latest series is called Claws and Flaws, an ongoing project initiated in 2014; in recent years, she has started reusing works in multiple series. She is also the first-place recipient of the 2015 Curator’s Choice Award, a prize bestowed by CENTER, a not-for-profit photography organization in Santa Fe.

During her acceptance speech for the Curator’s Choice Award, Sziládi spoke candidly about her process: “The figures in my images, like most of us—including myself—are caught constrained by mobile devices, and a certain amount of image consciousness. I aim to create a disjointed sense of time and space that reflects the disruptive way [in which] the digital world pervades our everyday spaces and behaviors.”

Working by composite allows Sziládi to juxtapose multiple sharp moments in a single frame, to play with scale, and to create focal points that compete for our attention. She includes perturbing elements that, as she said in her speech, “belong, and don’t belong, at the same time.” The result is an uncanny, noisy circus, one with a dress code and that encourages visual transience. Take her rendition of the Three Graces, “Untitled (Grapes and Graces)” (2010/2014). When photographed, the subjects posed for a “selfie”; Sziládi took a spontaneous shot. She added the background four years later, after capturing the screen image of a Tuscan grapevine from inside a convention center. Nothing looks quite normal, but it feels okay. Not just because we relate to this innocuous gesture, but because the absurdity of the final image is offset by a cheeky wit.

Sziládi brings up Sherry Turkle, director of MIT’s Initiative on Technology and Self and author of 2011’s Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other. Turkle’s studies are focused on the psychoanalytic implications of digital dependence on the individual, and the “subjective side” of our relationship with mobile technology, computers especially. Referencing Turkle, Sziládi mentions that media and technology have increasingly become intimate, living entities; sophisticated robotic, interactive models have been developed to nurture emotional connections in research hospitals and care units. Often, patients come to project consciousness and transpose emotions onto their androids, now guardians, pets, or sex partners. Turkle also describes a culture of normalized digital narcissism, in which anxiety is suppressed in order to broadcast a performance of endless exposure. “I share, therefore I am,” Turkle writes. Our reliance on technology to mediate identity becomes pathological, automatized, and symptomatic of a wider human disturbance. “As I go through [my] images,” said Sziládi during her speech, “I ask myself whether the image maker, subject, and audience have now become the same person.”

Despite its contemporaneity, Sziládi’s work suggests a deep primordiality: connection. Displays of mimicry and repetition are not modern phenomena, and they appear frequently in Sziládi’s work. People gesticulate, mirroring one other in posture and dress, and with devices omnipresent, scenes of surveillance—narcissistic and otherwise—are a reasonable afterthought.

When asked if screens and devices are a part of her morning routine, Sziládi responded via email: “Yes :(. But I try to check them at least half an hour after I wake up, and only briefly to make sure there are no emergencies. And then later attend to whatever needs to be done.” Whatever it is that needs doing, one hopes that in the constant and immediate culture of connectivity—that ever-expanding, immersive virtual web—Sziládi, as with the rest of us, can make greater space for the organic, breathing world.

For more information on Monika Sziládi, visit www.msziladi.com/.

All photos © and courtesy Mónika Sziládi.

Arianne Di Nardo is a writer and curator with a focus on contemporary photography. For more information, visit www.ariannedinardo.com.