Whatever I remember of her, my mother behaved nothing like her sister. The two immigrated from México Estado de Guerrero together in their teens. The border was wide open back then: you needed a coyote and the journey lacked amenities (food, tampons, etc.), but there wasn’t the same level of mass death there is today, which is how a woman like my Aunt Mimi made it. They found work in maintenance, and Mami, so smart, so assertive, moved up the ranks to manager, eventually founding her own housecleaning company. She met Dad, a white engineer, forever alone, at a neighborhood association meeting, and soon afterward, the world came together; she got her green card, sold her business, and dedicated the next phase of her life to the art of motherhood: cooking for us, telling us stories, pushing me academically (“Take advantage of opportunities I never had, Mijita”), conferring waves of feminine wisdom (“Select a partner with your same sexual drive, girls; don’t end up miserable”), never picking up after us or lifting a finger as it pertained to housework. That job fell to someone else, someone she paid. “If I don’t ever have to clean again,” she said, “Dios mio, I won’t.”

Then came the brain wars, though truthfully, I’m not sure what best to call it: Misfortune? Neglect? The shitty end of the bell-shaped curve? Life?

Mami insisted she had fibromyalgia. Whenever the latest woe is me commercial came on hawking the newest painkiller, Mami commanded our attention: “That’s me!” It didn’t matter that the actresses were always turkey-necked and white, performing a dance most closely resembling bachata (“CrescendraTM helps me move!”). These women looked unflinchingly into the camera and related stories of breakdown that for my aching Mami, a woman that carried aloe spears in her purse, sounded all too true.

“Do you see, girls? Do you see how nice it is to dance with a man?”

Invariably, what framed these cheesy portrayals of white health were her two upper-middle-class adolescent daughters splayed out on the couch.

“Will somebody in this house that’s young and espoiled and without pain PLEASE set the table?”

The best way to deal with Mami was to pay her lip service.

Ya voy! Right away! Anything you say, mi pobre madre who’s given me everything!

Say the right thing, then go on watching TV, wait for Dad to come home and assure every place setting has a salad bowl. Dad himself advised as much.

“Don’t react, Birdie,” he said after her blowouts, “just tell her, ‘Yes, Mami, how else can I help?’ Once she hears that, you can do whatever you want.”

I was quite convinced I had inherited my father’s mathematical mind, and so I treated Mami as if she was a calculus problem, a leaky cone requiring nothing more than the understanding of change rates—how brava is she?—to plug her up.

My younger sister Ceci was different. She never understood math, hated it in fact.

Someone telling her to do something, set the table, for instance, sounded more like an insult than a plea.

“How can you have pain if you do nothing all day, psycho?” Guns blazing. How Ceci approached life.

Mami responded in predictable Latina fashion. First, there was denial: “¿Psycho? ¡Yo no soy psycho!” Then, retaliation: “Sneak!” Then came the friendly fire: “¡Y tu tambien, Cabra!”

Translation: can’t you see, my precious daughters, how much I love you?

There were certain triggers in my family: names, nicknames, weapons used to defend yourself from your blood.

Before the first bomb of the brain wars dropped, there were certain triggers in my family: names, nicknames, weapons used to defend yourself from your blood. Whereas Ceci went the Urban Dictionary route—she once called Dad a creeper—all Mami’s nicknames came in the form of muddled verbs, the animal kingdom, handicaps. In other words, first generation. Take for instance Mimi, or should I say Tia ¿Dónde-Me-Limpio? Aunt Where-Do-I-Wipe? Mimi, succumbing at birth to nerve damage, walked as if she just stepped in a pile of fresh dog poop. As girls, we mimicked that ratchety gait, Mimi perpetually seeking out a curb.

“Niñas!” Mom said whenever we did so, an amused smile spread across her face.

Whatever Anglo abbreviations or baby babble that made up other people’s nicknames (“Gav? This is what his parents call him?”) weren’t the basis for ours; ours came from mess-ups. Maybe once as a little girl, you snuck into an R-rated movie with Raul, your supposed cousin, and maybe he blabbed about it to everyone for reasons you’ll relate to no one, not even your sister: henceforth you will be known as Ceci La Sneak. Or maybe you’re introverted and mostly calm, but in one unfortunate instance, you exploded at the DVR timer: I dub thee Cabra, as in Loca como una cabra, crazy as a goat.

God, just thinking of that word makes me boil over.

Dad was always just Dad. Pobresito never felt right about the nicknames. He defused our bickering with labors:

“Driver’s side was low, Birdie, I topped you off.” And time: “Anyone up for the ballet?”

And good old-fashioned white person consideration: “Sit down, my angel, I’ll make dinner tonight.”

But no amount of love could quell the aching that lurked inside my mother: her complaints worsened to the point she stopped hosting her weekly lunches for the wealthy suburban Latinas (Las Buenas, they called themselves). Dad did what any concerned loved one would do: he took her to see a rheumatologist.

Psoriatic arthritis. Mami loathed the diagnosis. To her, it implied bad skin. “Yo no soy una sucia,” she said. I’m not dirty.

They tried this medicine and that without any effect until they settled on a strong immunosuppressant given once a month like chemo. It was so strong, Mom had to take a TB test. This too offended her.

“Only indios get tuberculosis!”

“You are an india,” I said. We all were: Mami, me, Mimi, Ceci la Sneak to a lesser degree with the bushy eyebrows I envied and the armpits requiring excessive shaving I didn’t: we all looked like a band of Pocahontases with white-old Dad our colonial captor.

“I may be india,” she said all regally, her posture ostrich-like, “but I am not a peasant.”

The TB test came back negative and Mami started the medication. For four months, she couldn’t have been happier. Not only did the infusions justify all her prior complaints, it actually made her feel better. The woman that once disparaged all physical activity (except sex) as low-class began doing pushups on rubber balls beneath the tutelage of personal trainers.

“Promise me you’ll never neglect your core, mijita.”

When her first headache hit, we thought, The old Mami’s back, but then the changes started: solitude, listlessness, vomiting. All of a sudden, she couldn’t open anything sealed with a screw top, started jumbling words. It all boiled over on the eve of the brain wars, the night the Pope died.

“Respeto, mijitas,” she implored as we surfed through channels, “El Papa—que Dios lo bendiga—has passed out.”

I shook my head at Ceci from our crumb-infested sectional as if to say, Give Peace a Chance.

“Passed away,” said Ceci, “the Pope passed away, not passed out.”

The disdain you’d normally find in Ceci’s words gave way to concern, real daughterly concern, as well it should have, for Mami, despite an emotional tendency to mix languages, spoke English beautifully. Back in her maintenance days, the story goes that she practiced her pronunciation at 4 a.m., an hour before her first bus; late at night, dead tired, her hands swollen from hot sheets, she turned on the TV to watch Magnum P.I., NOT for Tom Selleck—“Never trust a man with facial hair, Mijita”—but for the grammar. I can’t tell you how proud I was to hear her reprimand my teachers—“In my culture, sharing answers is NOT cheating”—accent be damned. She was the lone member of Las Buenas to use adverbs (low bar, I know). All that effort, and very quickly, those language centers began to disappear before our very eyes.

“Don’t worry, Lady,” said Ceci, coming off the couch and giving Mami a neck rub, “I know what you meant.”

“Gracias, Mijita,” said Mami, “you’re very…¿cómo se dice?”

Throughout dinner, Mami kept on trying to tie her hair into a ponytail with a wristband that wasn’t there. “¿Cómo se dice?” she repeated, “¿Cómo se dice?”

Dad went to work the next morning. Ceci and I slept in late as always. By the time the hunger of outstanding laziness hit—“Did you eat breakfast? Lunch? Should we get something?”—Mami’s neuro Nagasaki was underway. Did we notice? Did her uncharacteristic silence dent our torpor in the slightest? Could we have been attentive adolescents and awakened early to cook the ailing woman breakfast, huevos con chorizo along with her favorite subscription-only gourmet coffee brewed the only way we knew how to make it, i.e., stirred in like Nescafé?

Of course not. Damn retrospectometer. Makes everything look so easy.

We ran baths for ourselves. We soaked. We shaved our legs, moisturized, blow-dried our hair, straightened it, applied subtle hints of makeup.

What, instead, did we do? We ran baths for ourselves. We soaked. We shaved our legs, moisturized, blow-dried our hair, straightened it, applied subtle hints of makeup.

And when at last the two preciosas came downstairs ready to begin the day, how did we announce ourselves?

“Mami! We’re hungry!” No response.

We looked in the most unlikely places first: Dad’s studio, the garage, below beds, before we found her kneeling on the floor of her walk-in closet. She truly believed there existed a secret tunnel to Mexico between where her dresses hung.

We tried to pry her hands from the clothes hangers. “Necesito oscuridad,” she kept on saying, I need darkness. These were her last words to us.

Ceci—I’ve never seen her move so fast—called 911. Dad met us at the hospital. They admitted Mami to the ICU, and for days, we received little in terms of answers. Each time the doctors briefed Dad, we eavesdropped from behind the nurses’ big mobile computers (COWs they called them), then played dumb.

“¿Que paso, Daddy?”

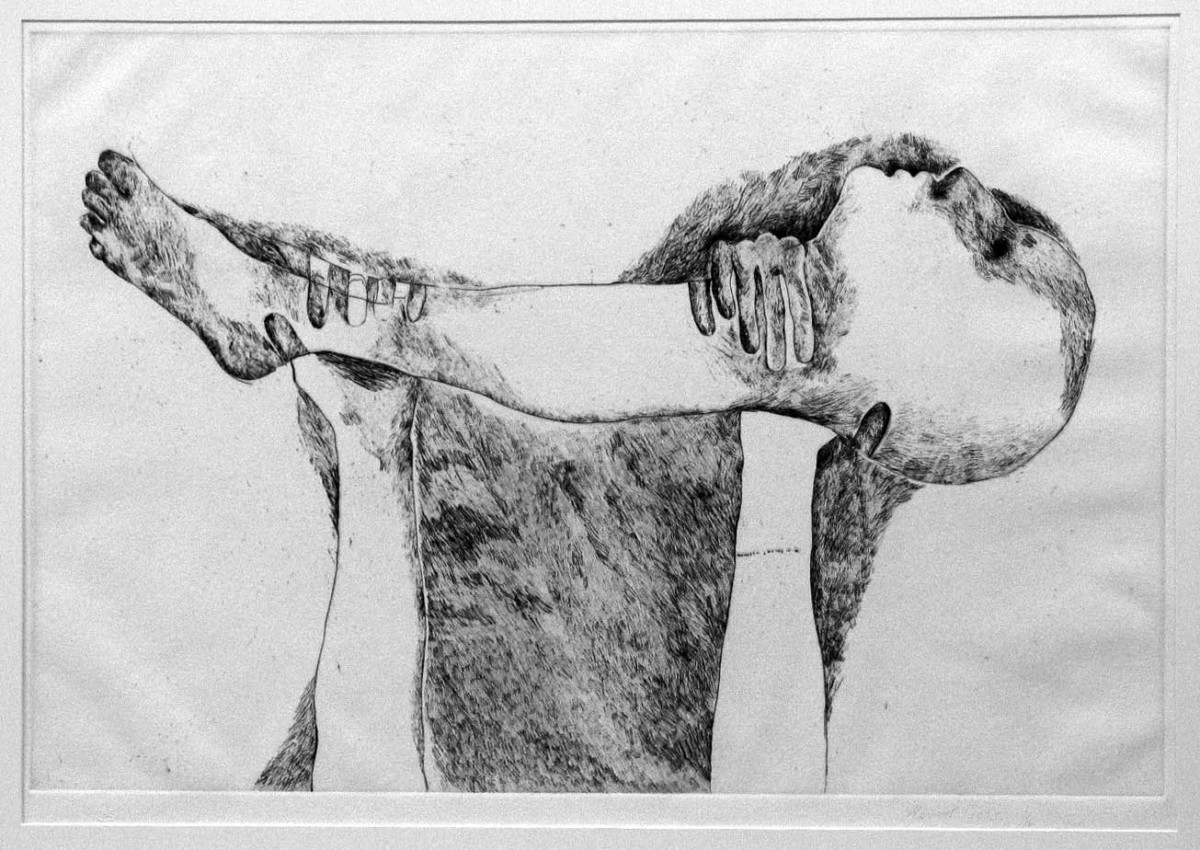

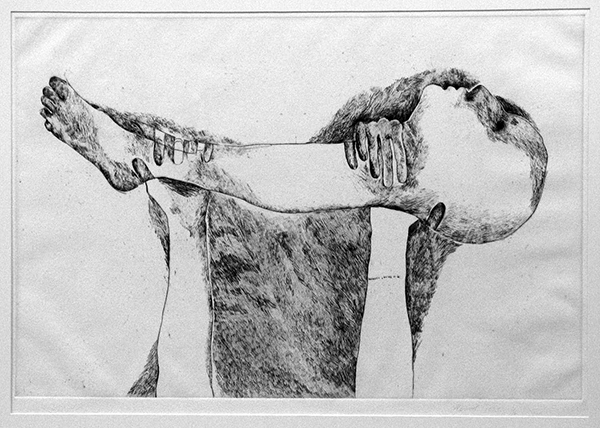

Those brief moments we were left alone with Mami—because during those first weeks, there was always SOMEONE around her, someone to clean her or check her temperature or stuff her hands into mitts—Ceci and I, like two Mexican Rumpelstiltskins, poured out our grief via small acts of violence, bruising ourselves, pulling out hair, pulling out her hair, while Dad just looked on.

We pelted him with questions: Why is she moaning so much? Why do all the doctors look so worried? Can’t she hear us, Daddy? Our pressing amounted to bullying, the only way to draw anything from him.

“She’ll pull through,” he said, as if arriving at the sum of some grand calculation. “She’s got to.”

We believed him.

As much as the nurses hugged us and prayed with us and implored us to stay positive, Mami kept deteriorating, that much was clear. What started off as confusion quickly turned into flailing, the desperation of a fish out of water, followed by deep, deep sleep. The doctors connected her to a ventilator, and with each day, she lost presence in this world. Tubes began to replace brain circuits: for feeding, for breathing, to keep her blood pressure up, for poop.

“She’s my easiest patient,” said the phlebotomist.

I stopped caring who was around. Whenever they came to draw blood, I spoke to her out in the open. “Digame que duele Mami.” Tell me what hurts.

But Mami just lay there as the needle plunged in and out of her forearm, the blood streaming out of her like juice from a juice box.

“She’s my easiest patient,” said the phlebotomist.

The doctors insisted they knew what was happening but not why. After a lot of debate, they cut out a piece of her brain and sent it to microscopes across America. Not long afterward, a set of infection doctors descended upon us like cops. The fact that Mami grew up “south of the border” inspired them to no end: Was “Mom” raised in adobe housing? Had “Mom” been in contact with livestock? Where did “Mom” buy her goat cheese? I despised their feigned empathy. They asked for childhood pictures, in particular, one that might show a fly bite below her eye.

All I found was one of little girly Mami at a fair with the dad she no longer knew, the same man that fathered fifty such children from more than thirty woman scattered across Mexico. Sure enough, Mami’s right eye looked swollen, though not violently so, more so as if she’d been made to cry by a boyfriend.

“Mami was beautiful,” said Ceci, “wasn’t she, Daddy?” “Still is,” he said.

Digging up old pictures was one thing: someone had to deal with the crap of life that began sprouting up, the updates to long-lost family and the parking validations and the doctors’ notes to assistant principals and all the Honeybaked Hams that arrived via courier, each member of Las Buenas being both generous and idiotic. Thus began my new life as an administrator, or should I say, the brains of the operation: I organized, I documented, I inquired, I googled, I consulted atlases of anatomy, I eavesdropped on other patients’ convos, I built what I thought were large spreadsheets: anything quantifiable regarding my mother’s care, I piled onto my plate like bolillos at a bakery.

My responsibilities grew, and the idea of returning to high school, of finishing senior year and going to college, seemed stupid.

“You’re a National Hispanic Merit Finalist!” said my counselor before she figured out why.

In my mind, I wasn’t dropping out. I saw myself more like Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of a new corporation named Brainheal or ManageMami, Inc. If not me, who?

Someone had to lead.

Dad, meanwhile, stayed in the background, the background being the bedside.

Day and night he stayed with her, at first: when it became clear the biopsy results would take much longer than expected (“We sent the slides to Panama, where they may have more experience with this”), we begged him to give just 1 percent of all that TLC to himself. In typical Dad fashion, he indulged us—he always indulged us—by pushing it at work, not eight but twelve hour days. Every morning he awoke at the bedside, ate the breakfast off her unutilized tray, showered in her unutilized shower, kissed whatever small space on her forehead might not be stained with iodine, and returned after work, when he kicked over a stool, rolled up his sleeves, and gave my mother his best (translated) show:

Ahora que I’ve lost todo to you,

Tell me que you wanna start something nuevo,

Y it hurts mi corazon you’re leaving,

Baby estoy grieving

Tea for Tillerman, track 3. If you took all the track 3s that ever existed and pit them against the track 1s, who would win?

Dad performed Mami’s favorite songs every night at shift change, 7 p.m., the best way he could, on an acoustic guitar that for as long I remembered he’d stored in the attic. At first, it weirded out the staff but soon enough they couldn’t help but take in the music. Right where smell ends but sound carries, someone always stood, sometimes a respiratory tech on a slow night, sometimes a doctor to steady his nerves.

“What you’re doing brings soul to this place,” said one of the interns.

“Oh Daddy,” I said one night while packing up his guitar and unpacking his work clothes, which somehow never wrinkled, “I can’t stand being stuck in the middle like this, I want this just to end.”

I repeated it louder this time, above the beeping and pumping: Can’t this just end?

But Dad just kept humming as if the stylus inside his brain had slipped out of its groove and played the same tune again and again.

About fifteen different doctors rushed up to us the day the biopsy result came back, each with a different story, each emphasizing the same: your mother has parasites, parasites she brought to this country from Mexico, parasites she’s lived with for years. It’s possible, they agreed, she could have lived with the parasites longer, that the body-parasite peace may have continued, but the arthritis medicine lowered her defenses, and so the parasites spread to her more vulnerable places, places like her brain.

We’ve killed the parasites, the doctors said, but the damage was irreversible. “What do you mean, irreversible?” said Dad.

“What you see here cannot be reversed,” replied one of the doctors. “We believe she will never recover function.”

For all the hoopla in making the diagnosis, interest in what to do with my mother quickly receded: they moved her to a low-intensity unit where the doctors made nothing more than guest appearances and the nursing took place via intercom. It didn’t take more than a couple of weeks before we were in the Solarium, gathered there by the social worker, who, while arranging the furniture, knocked over a cylinder of Domino Sugar.

“Pard-own-ay.”

This same woman, once the doctors arrived, told Dad her job was to “educate” us about life after the hospital. Learning from neurologists the mechanism of lip-smacking (“lower brain, unfortunately,”) and blinking (“actually we call this tracking, a middle brain instinct, I wish it meant something”) was one thing: hearing a woman with an Associate’s Degree lecture Dad—an aerodynamics engineer that built drones before drones became drones—was another.

“She’s a pendeja,” I whispered in his ear.

Dad gave me a look that said, Yeah, but so are a lot of people. The social worker was aggressive, I’ll give her that:

“Do you want your wife to continue to suffer like this or do you want to give her the opportunity to have things occur naturally?

Dad said we didn’t know.

“You’re the primary decision-maker, is that correct?” she said.

“We make decisions as a family,” said Dad. “Isn’t that right, Birdies?”

The doctors recommended taking Mom off the ventilator and stopping all care for reasons of futility, as in, they felt they were pumping nutrients and oxygen into a body devoid of meaning.

“Wouldn’t she die?” said Ceci. “Are you saying you want to kill her?”

But Mami wasn’t the hospital’s first rodeo: they took us to the bedside, where a young doctor named Blackhawk awaited.

“You don’t need gloves,” he said.

I went last. With hands as soft as soy milk—God knows how much disinfectant he’d squirted into them—he slid my fingers into Mom’s eye sockets and drew up her eyelids so that it felt like I was gripping a bowling ball.

“That nerve right there’s the most pain-sensitive area on the human body,” he said, pressing down on my fingers.

He withdrew his hands and started flinging jacks at her face, imaginary ones. His fingers came not an inch from her eyeball and yet, it was like nothing: Mami’s eyes just floated there like buoys on the ocean.

Blackhawk shook his head after each toss. “Negative visual threat. Lack of higher function.”

After that, he showed us Mami’s scans.

“I hate the term ‘brain-dead,’” he said, encircling a really dark spot with his laser pointer.

“I hate the term ‘brain-dead,’” he said, encircling a really dark spot with his laser pointer. “People think if you’re not brain-dead, you’re brain-alive, which, if this was my own loved one, wouldn’t be the preferred nomenclature. Can she yawn? Yeah, that circuit’s intact. Can she hock up phlegm? You see those wonderfully preserved white myelinated nerves right here. But can she move? Can she think? Can she process all the million bits of data from her eyes and ears and generate an action we deem consistent with the woman you know as your mother?” The red dot pulsated in a well of nothingness. “Unlikely. Like 99.99999 to infinity percent unlikely.”

In front of him, in front of her, I managed to hold it in, but later that night, in an old mailroom, I cried so hard I had to pinch my own eye socket nerve.

Enough, I thought.

We had to let her go. I was prepared to dial down the oxygen knob to 0 percent and watch her do nothing, no gasping, no choking motions, just a simple fade-away, a smartphone powering down. Inertia made her that to me. I’d heard some doctors call her “Rock,” as in, “Bed Twelve’s a rock.” Dad never liked this nickname and one time, he said so.

“Jerks.”

Not to their faces or anything, but once they left the room, well out of earshot. He said the same to the parking garage bums that asked for money with intricate, impossible stories: “Jerks.” He’d given them the cash, and we were already driving away, but he still had to say it.

Every week a different yet equally bitchy social worker called us into the Solarium and asked us if we were ready to let go. And every week, Dad made us take a vote.

“Those that think we should stop—and Birdies, it’s okay if you do—raise your hand now.”

Only one hand ever went up: mine.

Little known fact: when it comes to patients like my mother, hospitals don’t just kick you to the street. Sure, there are the shit-shows, the cases in Florida that grab headlines, but the real way hospitals discharge patients like my mother is through training. You’ll be privately ruing the hijacked state of your life one morning in her dry-as-a-bone bathroom when a large black lady with a crate on wheels will knock at the door. I’m dietary, she’ll say, or maybe, I’m wound care, I’m respiratory, I’m the IVs, and for the next four hours, she’ll detail just how bad her kids are or how much she likes Friday jambalaya, all the while performing the small yet detailed tasks that sift life away from death: This connector, make sure to flush it three times a day. See one, do one, teach one. She’ll demonstrate the jet-like performance of the suction engine, let you probe the Yankauer into the netherworlds of her throat, then she’ll kick up her heels on a much-used recliner and play stupid: Ma’am oh ma’am, she’ll say, whudoIdo if I see bone and the wound’s got fecum matter? She’ll confer upon you a certificate of completion exactly one minute before lunchtime, snap tight the handle of her roller crate, and hum church radio all the way to the elevator, whereupon an administrator will enter the room.

How’d we do?

A stranger will appear at your home one afternoon with measuring tape and a stud finder.

The bed we can fit through the window, let me ask you this: do you have hammock hooks?

It’ll come down to one meeting.

We’re all set, just need one signature here.

They know you’re a ball buster, they know you know your shit, they know you’ve predicted nothing but gloom for this body, but they’ve also studied the family dynamic, the sister that thinks she loves nursing now, the dad that can’t say no. That’s who they focus on, that’s who they hand the ballpoint pen, that’s who they draw up the papers for, that’s who, after the signature—like closing on a house—they delightfully pat on the shoulder. Any changes and bring her back. Everyone shakes hands and they say it again as if we’re on tape, words they know might be heard in a court of law: You can always bring her back. And once they’ve abandoned you with the ambulance guys in tow, who strap the body like they might planks to a surfboard, the man you call Dad will say it a bit louder this time.

“Jerks.”

Bring her back we did. Mom averaged a hospitalization every four-to-six months. You could stop at a gas station for no good reason, check the pressure of your tires, and chances were if you were running low up front, you could check Mom’s rectal temperature at home, smell the urine a little while dumping it out, and know exactly what to do. 100.6 with mild hypoactivity? Flush catheter thoroughly with 60ccs of saline, allow two weeks. Mildewy and raw with a hint of fruit, i.e. ketones? Aggressive rehydration with Lactated Ringer’s, re-check in three days. Sheets soaked, 103.1°F, pus? LAN line speed dial #3, or if not available (if Ceci La Sneak has again failed to return the handheld to its hub for recharging), dial Contact EAT, Ellington Ambulances of Texas, enter frequent client info, pack bag, await two-to-four week hospitalization.

Five years it happened like this, five years of shifts and turnings and slipped feeding tubes dribbling Carnation Instant Breakfast in the middle of the night. Five years of PEGs and TPN, PICCs and CPAPs—I promise you, it’s no joy talking like this—silver sulfadiazine and soap sud enemas and home-shaken Vancomycin that when infused too fast make the skin go red. Five years of trachs and suctioning apparatuses and freaking out about moisture, I can’t tell you how much talcum powder I’ve inhaled. Five years of staying in on Fridays and The University of Phoenix and mitigating stupid Mexicans’ dreams (to Las Buenas: Eso no fue ella, fue un reflejo, su cerebro de vibora, That was her reptilian brain, not her). Five years of discussing it during the uneventful moments, living for weeks at a time like we just accepted it, then in a snap—a deeper cough, black stuff coming up, skin gone all papery—sitting beside him in the Solarium, another social worker talking to us, Dad turning to me, me looking outside: Do you want her to continue to suffer like this or do you want to give her the opportunity to have things occur naturally?

For all the tension that boiled over during Mom’s first hospitalization, we grew close to everyone on the wards and ICUs. They respected how well we cared for her—“No bed sores! Incredible!”—and we, in turn, provided them with entertainment. The staff enjoyed Dad’s performances so much that he recorded (and I burned) a CD, Songs for Elenita, eighty minutes worth of 1970s adult contemporary covers: Neil Young, Joan Baez, Simon and Garfunkel, Cat Stevens (Mami’s favorite), all recorded with hospital acoustics: random beeps in the background, the announcement of “Code Blue, Four Echo,” during “I Got a Name,” etc. It was the kind of CD that staff members thanked Dad effusively for and encouraged him further—“You ought to play concerts, man!”—then discarded into the biohazard. Such was life at the hospital. I found one smeared with some sort of unrecognizable fluid once. It didn’t deter Dad. Not much did.

“Esta loco.” He’s crazy.

Mimi’s observations of white people with their white behaviors sounded a lot like children observing pandas at the zoo.

“Pero todavia se ve bueno.” But he still looks like a good man.

The way Mimi fell back into our lives was through one of Las Buenas, surprising to us since we hadn’t seen her since that first discharge. We’d communicated off and on for some time via her Cricket phones—no voice greeting, constantly disconnected—updating what we could, when three weeks incommunicado became three months and then some, Mimi having disappeared.

Such was her life. She was the type of Mexican that moved a lot, sometimes back to Mexico, sometimes to ghetto housing to take care of children, sometimes across America, to the lettuce-picking or meat-packing parts. She migrated to these areas not for the jobs but for the culture, the men.

“Mexican men have, ¿cómo se dice? A must? A musty smell that is very sexy, mijitas,” said Mami. Previously.

There she was, tagged in a Facebook photo, same old Mimi with the braided hair longer than her spine, the bum leg, same silver-rimmed teeth that gleamed whenever she smiled. Mimi always smiled, no matter how bad things got: it was something I missed about her, about life. For all my mother’s residual facial tics, I never confused one for a smile.

Mimi was back in the city doing maintenance, only now on a small scale, condos, duplexes, the cool loft of one Las Buenas’ daughters, where I found her. Fucking pigsty! I met her there on the first day of my mother’s final hospitalization: bean-crusted pots, half-empty bottles of Moscato, sheets with evidence of period sex, and yet Mimi enjoyed making it all look neat. It was the week of Christmas, and she had spread out a Nativity scene for the little brat, one purchased with her own money.

The administrator in me couldn’t help but cut to the chase: “I have a problem with Ceci. We don’t talk.”

Who knows how these things take on so much rancor: my sister and I lived beneath the same roof, ate the same food, wore the same clothes (stolen from the other’s closet), but couldn’t co-exist in the same room, spat at one another if by chance we shared the service elevator.

Surreptitiously. Like with no one looking. At her heel. “Did you just gleek at me, psycho?”

“Did you just move your mouth?”

Five years of disputes may have given us specialized vocabulary—“There’s no neuronal perfusion! Nada!” “Glorify God in your body, and in your spirit, which are God’s. Corinthians, retard!”—but really it was the same old war, me acting pompous toward her, her disrespecting me, both of us clamoring for the love of our parents, one of whom was either suffering or struggling to survive.

“I convene the summit of pecking Birdies,” said Dad at the bedside, the last time any of us had spoken.

Our sour faces couldn’t help but dissolve into unwilling smiles.

“So stupid.”

Seated there all smiley and warm, the guitar positioned classically in his lap, a week’s worth of growth carpeting his throat, he looked like one of his heroes, the Cat of old, a man aware of all the bad stuff in the world but resistant to its awfulness.

“So glad the family’s back, my dears,” he said. “And now let’s talk about the elephant.”

Each of us tried to discuss respectfully, and we did, until one word muttered by God knows who triggered a bullet followed by shelling (“Do you even know how addition works?”), bombs (“Have you even kissed a boy, twat!”), all-out war that could only be stopped by one thunderous crack.

THWAAAAAAACKKK.

“Daddy!”

There was no need for the intercom: the nurses rushed in to find the head dangling from the strings of cat gut, Dad’s guitar smashed against the bathroom door by one Paul Bunyan-like swing.

He folded the guitar in two, handed me the remains, and walked out.

He folded the guitar in two, handed me the remains, and walked out. Amidst all the commotion of hospital personnel lay the body formerly known as Mami. She never batted an eye.

“Es la sangre?” I asked Mimi, after relating these events in a loft that made me thankful my parents hadn’t over-spoiled me, in a language I’d spent my life butchering, a language had started to forget, Is this our blood? Was sibling acrimony like this heritable, some DNA coil passed on chromosome X generation after generation, or was the story of our family just a matter of statistics, the roulette wheel falling on red too many times in a row?

Mimi smiled, her front teeth’s silver linings hidden ten feet in the air. Questions as such weren’t part of her world view: stowing princesa’s Tupperware atop a step ladder was. And God knows I respected that.

I could have shamed her about not visiting my mother. I could have said to her in elaborately translated Spanish, “You abandoned our family.” The entire album of perturbing selfies with Mami I’d taken with the intention of making people feel sorry for me, I could’ve shown her. I certainly wanted to. But I needed her help.

In big block numerals, on a Post-It, I printed Mami’s hospital room number as well as the address, clear as day for anyone, including the illiterate.

“Gracias,” she said, attaching the note to the frizz of her cardigan sweater. Before I left, she asked if I might not practice my Spanish more at home, perhaps with Dad.

A loogie, a big fat yellow one that bobbed up and down with each lower brain-induced cough, awaited her at the bedside.

“Me esta hacienda burla,” she said. She’s making fun of me.

But it only took a couple of minutes with her sister’s vacant stare to see this wasn’t the case.

Mimi spent hours with her. She talked long and pointlessly with the maintenance men and nodded at the doctors’ every word. I never saw her acknowledge the body that was my mother, however. You could see at times a hint of revulsion underlying Mimi’s smile, the underfold of her nose quivering as if something had gone foul.

I know she spoke with Dad. And I couldn’t help but overhear her and Ceci laughing like hyenas in the cafeteria one night, which provoked a spike of jealousy in me, but only a spike. When she and the social worker appeared at the bedside, their arms locked in the manner of middle-aged women comfortable with one another, I knew the pendulum was about to swing in one direction. I just didn’t know which.

We all gathered in the Solarium the next day where fresh Danishes awaited, a box of gourmet coffee, leather Ottomans pre-arranged into the perfect configuration to maximize doctor-family comforting.

Ceci arrived first, then Mimi, then me, and for a good ten minutes, a loving family sat in silence looking out different windows.

All the Ottomans were taken except one.

“We’re just waiting on one more person,” said Dr. Blackhawk.

An elderly black man walked in and sat right down, resting his cane right beside me. Blackhawk patted him on the shoulder.

“Private meeting,” he said.

“Oh shit.” The man left so hurriedly he forgot his cane. Not a minute later, he was right back where he started, picking it up. “Sometimes you do stupid stuff.”

In a snap, Dad appeared behind me, not touching, but close enough to feel him. “Hi, Birdie.”

He’d shaven, and for a minute I thought his baby face might be someone else’s, but once he sat down and crossed those skinny legs, I knew it was my Dad.

“I’m sorry I lost my temper our last visit,” he said. “It won’t happen again.”

I stood and hugged him the way you do in those situations, awkwardly, wishing you had privacy, but with joy. I slung my purse over my shoulder, thinking, That wasn’t so bad, but nobody moved, not Ceci, not Mimi, not Dad.

The social worker asked if I wanted another Danish, then she and the doctors left the room.

“Birdie,” said Dad, looking away, “your good aunt reminded us about something.

I don’t know how else to say it: I have been and remain only common law husband to your mother.”

There was more:

“It’s very likely I’m not genetically your father. 100 percent likely.” To Ceci: “I’m pretty sure I’m your father.”

So goes the story of my mother: years ago when this city was nothing, a woman crossed the border poor and monolingual. She worked day and night to reverse the misfortune that befell women like her, the abuse, the touching, the neglect. When the office building she cleaned moved operations to Dallas, she accepted the kindness of a young white engineer who gave her money, time, his bed (“I sleep on the couch anyway”), not a green card, however. This she earned herself, this Reagan gave her.

Regarding the man that impregnated her, we know nothing. That information—who he was, why he didn’t help her, why she preferred the kindness of the white man—remains in the black box of the woman’s brain.

We can assume the man was Mexican.

What is known is that the white man supported the woman. We know this man spent nights with the child while the woman worked. We know after months of this, he wanted more. During the rare moments the white man and the woman shared a day off, he proposed marriage to her, along the Seawall, at all-you-can-eat seafood buffets, at cultural events. “I’ll take care of you,” he said to her, “You won’t have to work.” With what love did he shower her, love that for so long had been lost in his circuits. “You’re my angels,” he sang to the woman and daughter, “my Mexican angels.”

Did she love him? She did, in her way. Who indisputably she loved was her daughter, baby Elena, me. She dreaded the notion I might discover wedding photos during my formative years and conjure questions. I cannot marry, she told the man in correct English, but we can continue like this. She swore her sister to secrecy. Soon enough, she had a child with the man, a child they named Cecilia. In the comfort of the maternity ward, her first but not last private hospital room, she agreed to a civil marriage, but this promise was forgotten. The man spoiled her. The past world of toil seemed someone else’s, not hers. The girls aged, and even preparing a lunch for them started to take on the tenor of a chore. Slowly but surely, her joints began to hurt. The unthinkable occurred.

I never saw him cry for her, but I saw him at her bedside for years running his fingers through her hair, strumming songs of love for her, addressing her as if it were she. He debated to himself early in her illness whether to disclose this information, but in the grand scheme of things, it seemed so trivial: so what if there’s no marriage certificate? So what if my X chromosome is not a part of her genome? Did I not raise her?

All the difference in the world as it pertains to law: Section 597, Title 40, subheading E, a hierarchy of decision makers should the subject—i.e. the patient—lose capacity to make medical decisions. Second decision-maker is eldest adult child, the first is spouse, legal spouse, not common law spouse.

Dr. Blackhawk seemed to take some pleasure in explaining the legalese. He moved his Ottoman in front of mine.

“What this means is, we’re on legal footing here. If you want to give your mother the opportunity to have things occur naturally, you can do that. You’re her eldest child, you make the decisions.”

He looked at Dad. “That’s right, Birdie.”

You can imagine the tears, the commotion, the accusations and denials and apologies and ridiculous-ass translating that took place in the Solarium that morning.

You can imagine the tears, the commotion, the accusations and denials and apologies and ridiculous-ass translating that took place in the Solarium that morning.

“Do I need to get a lawyer?” Ceci asked no one in particular. We entered separately and separately we left.

Dad wanted to leave last, held his hand out in gentlemanly fashion shaking his head, No, you go ahead, you, but I insisted.

“You first.”

People will make you feel guilty. They’ll come from the woodwork and contrive to know what they’re talking about. Ella lucha, she’s a fighter, siempre fue luchadora.

They’ll offer you everything—Si ya te cansaste, dejanos cuidarla, if you’re tired, let us nurse her—and some will give just that: they will journey forty-eight hours via bus and rub tea tree oil over every inch of her body and sleep in your recliner. They will watch telenovelas and make caldo de pollo and ask how many summers it’s been since you’ve been to México. They’ll laugh uncontrollably recalling the times as a child, the body now breathing unreasonably before you back-talked to her father or flirted with boys socially beneath her. They’ll mention it in an off-hand manner, You’re not really thinking of letting her go, de verdad?

But it’s not their decision.

Friday nights, our kitchen got so crowded—Mimi and her friends slicing vegetables on one side, Las Buenas with their coffees on the other, everyone holding hands during the prayer—that I found time to escape: to music stores, to the movies, to the park near our house.

While I watched the golf balls, Dad walked laps.

“I have a question for you, Birdie: do people my age go to the gym?”

There were times I’d see him stretching and tell myself, This man is not related to you, he is a stranger. But I guess any girl might feel the same way about her parents during moments as such, so what?

“He’s still Dad, cabra.”

It took some time (and intervention) to get Ceci and me talking, let alone on the same page. During our negotiations, Ceci snuggled with waterproof pillows beneath a fleece throw. Some nights, the Solarium got so cold that I’d sneak my toes into a corner.

“You’re such a child,” she said, pulling enough to cover my feet. “All you had to do was ask nicely.”

After I signed papers that told the hospital not to give Mami CPR if her heart stopped, the big debate became the ventilator: should we keep it on and wait for the next infection or unplug her right here and now?

“Disconnecting would be the most logical thing,” said Dr. Blackhawk. “If you want to be consistent.”

But to me what seemed most consistent was that Mami should go in peace, not with her sister in Mexico, not with her daughters at each other’s throats. It’s why I compromised.

Ceci and I agreed on the small things first, like terminating her cholesterol medicines and allowing the blood sugar to go where it may. Stopping the feedings proved difficult, too difficult: I found myself making arguments I didn’t believe, “She’ll suffer less if we don’t feed her,” though in my heart of hearts, I wasn’t sure if the part of the brain named Suffering might still be firing.

“Okay, you win,” I said, a sliver of me insisting Gracias a Dios, “we’ll keep the vent and the feedings. But no antibiotics when the next infection hits. We’re not bringing her back.”

How in Spanish do you say bittersweet?

“Do you two want to hug?” asked Dad. We looked at him. “Or at least shake hands?”

We followed an ambulance with non-flashing lights home, forever now. Ceci and I weren’t as close as we’d been, but we started to talk about the future.

“Things are good for the moment,” I said to Dad.

“I’m so happy you feel that way,” he said, “but things are always good.”

For awhile it seemed like it would never happen, as if my decision had altered the physical universe, as if the hurricane we awaited up and turned back. I started to feel guilty. Maybe she can live forever, I thought to myself, maybe she is luchando. The little cough that for so long sounded mechanical took the shape of words.

Ahhhhhwhrrrr.

Our? Our what, Mami?

Ahhhhwhrrrr. Ahhhhwrrrr. Ahhhhwhehhh. Alla? Alla donde? Go where?

The fever came with a fury. I never saw her so pale. Ceci and I began to bicker over things like Neosporin. She wanted to tank Mami up on fluids, which seemed reasonable with how dehydrated she looked, but a leader doesn’t waver. A leader stands her ground. God doesn’t need saline to perform miracles, I announced at dinner. They either happen or they don’t.

I found it difficult to think.

“I might road trip to Acapulco,” I told Dad. He wanted to hear everything, including the stupid stuff, things I knew wouldn’t take place. “Maybe it’s best if I’m not around.”

He hated the idea of me anywhere near the border, but didn’t feel right telling me no.

“If you go, call often,” he said. “To see if I’m all right.”

And then it happened. You think you know a body. Ceci called me into the room. “I can’t touch her, will you touch her?”

LOW PRESSURE, blared the ventilator. “Go tell Dad, get him out of bed.”

You prepare for a moment like this at nighttime, when the gagging’s bad and you can’t sleep. You imagine yourself calm and respectful, the one holding it together while others lose their head. You compose in your mind something formal—It’s gonna happen for me, Mami, I’m gonna live a good life!—things no one’s ever said.

I disconnected the tubing half-expecting her to move the way the doctors tell you.

And when she actually did move, when her tiny wrists rolled in on themselves a little, I cried and took pity on them by letting them hang—Why wouldn’t they?