By Humera Afridi

On the night of October 8th, I sat on the floor of Dergah Al-Farah, the Sufi mosque in Tribeca, contemplating the Divine name, Ya Jabbar, that translates from the Arabic as “Bonesetter,” or “Healer of Fractured Existence.” Ya Jabbar… Ya Jabbar… I muttered, riveted by the alchemical potency of the incantation. It felt apt. Seven years ago, on this day, a massive earthquake devastated great swathes of Northern Pakistan and Kashmir. Eighty thousand people died; whole villages toppled off mountain facades; dead buffaloes floated in the Jhelum River and the landscape, cracked and split into so many fissures, was transformed into a series of twisted, gaping smiles.

Sufi mystics believe we can actualize the Divine attributes, that the power to do so resides within each one of us. I reflected on the tragedy and marveled at how the disaster of 2005 had, indeed, for a while united Pakistanis in an unprecedented way. Unity, Faith and Discipline, the founding pillars of the nation that had rung hollow for decades, were dynamically revivified as the country contended with infrastructural damage and the emergency needs of 3.5 million displaced citizens before the imminent onset of winter. Mullahs, progressives, women, men and militants sublimated their differences and got to work rebuilding. In a feudal and tribal culture that places great value on the ideal of honor, it was the honorable thing to do. The country was a heap of broken bones but the bones were being realigned. In the shattering, a new potential had been born.

On October 9th, exactly a day after the anniversary of the earthquake, the Taliban hijacked a school bus in Swat, in Northern Pakistan, and shot fourteen year-old education activist, Malala Yousufzai. In the time it took for the bullet to pierce the bones of her head and lodge in her neck, the “house” that Pakistan has built for its citizens collapsed, revealing itself to be nothing but a makeshift shelter of broken sticks and airy, spectral at best. Over and over, the nation has attempted to rehabilitate itself by slapping plaster on its cracked walls—through bouts of martial law, alliances with Saudi Arabia and America, the fostering of border enemies to feed national bravado. But band-aids on broken bones are salves for the purely delusional.

There is something tragically dishonorable about a society in which a schoolgirl is compelled to take on the onus of advocating for her own education.

The time has come for Pakistan to heed the words of Rumi, “to do the work of demolishing/ and the digging under the foundation.” We can’t afford to waste another moment—the regressive ideology of the Taliban and their cohorts has so enervated the social fabric of Pakistan that only an education revolution can eradicate it. Progressive, secular education must become the bedrock on which Pakistan fashions itself anew and protects its citizenry. In Babri Banda, my father’s village in the Northwest of Pakistan, the Taliban actively recruited scores of school-going boys to fight the Americans in Afghanistan, deeming it a holy war that would garner great spiritual rewards. Two years ago, the Taliban placed posters on a girls’ school outside the village, threatening sinister consequences if the school wasn’t shut down. And then a suicide bomber did destroy the school on a Sunday morning. My childhood friend, Fazila, tells me, “The Taliban are everywhere. Like an ideology, everywhere and invisible at the same time. We don’t form opinions publicly, you never know who’s listening and what they’re going to do.” One Friday, during communal prayer service at the mosque, the malik made a speech condemning the Taliban practice of suicide bombing. Alas, there was instant retribution. Mere days later, gunmen on motorbikes shot at him as he was traveling home.

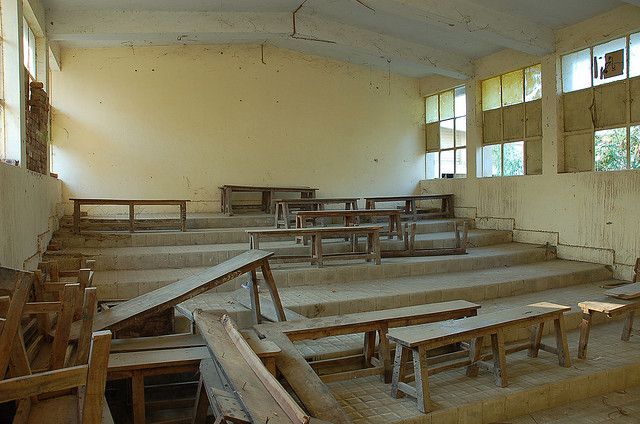

It is a ludicrous fact that the Pakistani government funds approximately forty thousand ghost schools. In actuality, many of these schools are abandoned buildings serving as spontaneous cattle farms and barns, homes to drug addicts and squatters, or as shelters in times of natural disasters. Or else, they are buildings that don’t physically exist but were purportedly built, with the funds disbursed long ago for their construction. There are schools that lie empty because the teachers assigned to them do not show up to work, though they are on the payroll. Many of these salaried teachers hold other jobs. A willful blindness enables and sustains this charade. There is no accountability.

Quite apart from the dire need to make education accessible and compulsory for every single child in Pakistan, the national curriculum itself needs to be updated and sifted clean of ethnic and religious discrimination. It is as urgent as oxygen to a person trapped beneath a landslide—that the curriculum be redesigned in order to root out rampant dogma and obscurantism from textbooks. After all, what value is there in an education that inculcates hatred, paranoia and conspiracy theories, that petrifies gender discrimination even as early as elementary school?

In 2011, as part of the Open Society’s Writers Bloc project, Pakistani author Kamila Shamsie visited Pakistani schools and perused government-issued textbooks to glean a sense of what Pakistani children were being taught in school. In a book that teaches the Urdu alphabet to first grade students, she discovered an illustration of a plane crashing into the World Trade Center. The caption below the picture stated: Tay—takrao, which translates as C is for Collide. Another alarming visual, that of a woman in niqab (a complete face covering that is traditional in Saudi Arabia but has become more popular in Pakistan in recent years) described the letter Hei for Hijab while the letter Jeem represented Jihad.

Safia Bibi was condemned to be flogged a hundred times; her rapists were acquitted.

There is something tragically dishonorable about a society in which a schoolgirl is compelled to take on the onus of advocating for her own education, amidst and despite death threats. Malala’s shooting has brought into sharp relief the ever-widening gender divide in Pakistan and the egregious absence of women’s rights. The truth is that the situation for Pakistani women began deteriorating in the 80s, under the regime of the Islamist military dictator, Zia-ul-Haq, America’s great ally in the Soviet War. It is to him that the Taliban owe their provenance for he created the ranks of the awesomely effective Mujahideen, the Taliban’s predecessors.

I vividly recall the anger and helplessness I felt as a girl in Pakistan, in 1983. That year Safia Bibi, a blind thirteen-year-old servant, was raped by her employer and his son. Unable to provide multiple witnesses to vouch for the crime, she was accused of adultery and deemed a “fornicator” under Zia’s draconian Zina Ordinance. She was condemned to be flogged a hundred times; her rapists were acquitted. I was thirteen when that happened, the same age as Safia Bibi. Seeing that this kind of violence against girls my age was permitted, I knew that to change the patterns of brutality and injustice, we would need to learn to empower ourselves.

The shadow side of honor—its dark twin, if you will—is shame.

The attack on Malala is heartbreakingly unexceptional. Misogyny is a mindset in Pakistan. Men are empowered and entitled to avenge themselves, if they so much as feel slighted. As casually as if he were tossing a stone at a stray dog, a husband resorts to physical violence to “reprimand” his wife, and the act is perceived to be an unspoken socially sanctioned rite of marriage. The absolute repression of self-hood and the inability to access and exercise basic human rights is the lot of the majority of Pakistani women, especially those in the rural areas. In a culture that places a premium on honor, heinous crimes are committed in its service. And the perpetrators of these crimes are ubiquitous, not merely confined to the ranks of the bearded Taliban. In May 2000, Bilal Khar—cousin of Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, Hina Rabbani Khar— threw acid on his wife, nearly killing her. He remains free. His wife, Fakhra Younus, found asylum in Rome where the Italian government covered the cost of her thirty-nine surgeries. Earlier this year, at the age of thirty-three, Fakhra Younus, committed suicide. In her suicide note, she declared she had given up because of “the silence of law on the atrocities and insensitivity of Pakistani rulers.”

And so it requires a stupendous act of courage for a woman to speak out in a chauvinistic society where violence is dispensed as easily as alms to a beggar in a bazaar. The shadow side of honor—its dark twin, if you will—is shame. And to the Taliban, fourteen year-old Malala’s eloquent blog entries and speeches—public and outspoken challenges to their warped ideology—are perceived as attempts to shame them.

As a Pathan woman from the warrior Afridi tribe, I am struck by Malala’s bravery and by the stupendous force of her father, Ziauddin Yousufzai’s, single-minded vision for his daughter. It is rare and exceptional for a Pathan man to speak so vocally about the rights of girls, especially when he is embedded in the very milieu whose social mores he is challenging. Pathans live by the ancient code of Pukhtunwali that governs tribal life and elevates honor and revenge above all else. It is said to date back to pre-Islamic times. A mere taunt can set off a blood feud—the sanctioned way to right a wrong— and is often carried down through generations. According to a Pathan proverb, protecting Zar, Zan and Zameen—women, gold and land— to the death, inspire a life driven by honor. Ziauddin’s progressive ideas about girls’ education are laudable and his candor all the more remarkable for this. I can’t think of a single Pathan man—including my own gentle father, who has a Western education and has lived abroad for many years, who would actively groom a daughter for a life of public service, permitting her to be photographed and filmed, when doing so not only breaks the covenant of purdah (which shields women from public scrutiny) but destabilizes the “honorable” status of the tribe. Pathan women are not merely their father’s daughters or their husband’s wives. They are communal property, owned by the clan.

The pull of tribal culture is intractable. No matter how far Pathans travel, how worldly their ideas, on home soil they are irrevocably accountable to Pukhtunwali. They must tolerate, respect and endure the stringent and hermetic codes of conduct—or else face badal, revenge. When I was eleven, a Kalashnikov-toting man approached my father and attempted to “buy” me from him while we were shopping in the Darra market. I distinctly remember the swarthy man in a brown shalwar kameez, stroking his moustache and undressing me with his gaze, as he tried to engage my polite, cravat-wearing father in negotiation, as if it was the most ordinary thing to do. In the paradigm of the tribal areas, it still is.

Although my family is quite westernized in certain ways, during my sophomore year at Mount Holyoke College, while I was immersed in a life-altering feminist, liberal arts education, my parents arranged my marriage to an Afridi cousin. I succumbed to the tug of tradition. And over winter break of my junior year, I returned to my father’s village in the Northwest Frontier, close to the Afghan border, to get married. I sat in purdah, excluded from the festivities. The sun didn’t touch my skin for close to four days. On the morning of the wedding, the women of my family dressed me in a gold outfit and brought me outside the house to an elevated cement water tank. They hoisted me up on it and directed me to turn slowly so that the women of my husband’s family and the scores of curious village women, hovering at the bottom of the well, could examine and appraise me. On subsequent visits to the village, even though I was now a “respectable” married woman, when I walked outside the gates of the family compound with other female relatives, snotty-nosed boys would hiss and run after us, behaving as though it was their God-given right to taunt women.

Indeed, the Taliban could well do with a refresher course in Islam, for it possesses a tradition of brave, forthright women.

When the mere sight of a woman, cocooned in a long chador no less, walking down a village dirt road can create havoc, imagine then the furor caused by Malala Yousufazai’s forthright and outspoken manner and her father’s encouragement of it! When Malala was airlifted to the CMH Hospital in Peshawar, an hour and a half’s drive away from my village, I telephoned a childhood friend. Fazila lives in a raw mud structure, is illiterate, and can’t write her name—but she has struggled her whole life to ensure the education of her four children, sons and daughters alike. Despite her circumstances, she is a progressive thinker, a visionary even, and I can’t help but wonder if it’s because she was spared the dogma spouted in the majority of rural schools. Fazila tells me that Shaziah, her daughter who is a year younger than Malala, has become consumed by a strange jazbah or passion. “‘We are all Malala, each one of us!’ Shaziah keeps saying.”

Ziaudin Yousufzai envisioned his daughter doing more than becoming a medical doctor, which is what she hoped to be. “She can create a society,” he said presciently in an interview in 2009. In her daring crusade for girls’ education, Malala Yousufzai is a modern-day prophetess. It is the legacy of prophets to be attacked, ostracized and demonized as they spread the light of their message.

Indeed, the Taliban could well do with a refresher course in Islam, for it possesses a tradition of brave, forthright women. What do the Taliban say to the fact that the Prophet Mohammad’s first wife Khadijah, older than him by several years, and the mother of his four daughters, was a fiercely independent and astute business woman? Or that his youngest wife, Aisha, 18 at the time of his death, disseminated his teachings and came to be known as the Mother of Islam and led an army to battle at the age of forty-two? What do the Taliban have to say about the Divine injunction for Muslims to seek knowledge even if it means traveling as far as China? The Taliban’s ideology is, in truth, reminiscent of the period preceding Islam, known as Jahiliyya, or the Era of Ignorance, a time of brutality and aggression and female infanticide. By contrast, the Prophet enabled social change in the seventh century, through gentleness, harmony and reason, attributes that are invoked in the Divine name, Ya Halim.

Two weeks ago in Manhattan, I attended the ten-year anniversary celebration of the Sadie Nash Leadership Project, an organization that equips young women to become leaders. The representatives were dynamic and awe-inspiring, their bright minds sparkling with ideas. I can’t help but think how mystifying and unfair that mere days later, in this technological age of Facebook, Twitter and iPhones, Malala Yousufzai was punished for her brilliance with a bullet in the head, that she lies in a hospital fighting for her life, when, instead, she could be encouraged and celebrated for her ideas and leadership like her peers in the United States.

Algebra, the branch of mathematics dealing with relations and operations, stems from the Arabic root word, Al Jabr, which translates as the “reunion of broken parts. It is linked to the Divine name Ya Jabbar. Each night, transported by the vibrations of the repeating middle consonants—Jab-bar, Jab-bar—I invoke the Bonesetter to cure Malala, so that she may return to being an avid school girl. I invoke the Healer of Fractured Existence, too, for an equation for harmony and equal rights.

Pakistan finds itself in the acutely uncomfortable position of being publicly shamed beneath a global spotlight, of being “outed” for forsaking the basic human rights of girls and women. But in an honor-driven society, shame is the fuel that spurs a nation to action. May extraordinary gestures of martyrdom by Pakistani schoolgirls and acid burn victims no longer be necessary. The words of the Sufi visionary, Pir Vilayat Khan offer an antidote: And what if this life is a malleable and workable dream, which can be shaped, restored, and beautified by our intentions and actions? May mindful education form the bedrock of an honorable Pakistan.

Humera Afridi is an Open City Creative Nonfiction Fellow at the Asian American Writers Workshop. She was the recipient of a New York Times Fellowship at New York University, where she earned an MFA in creative writing. In 2011, Humera was a Fiction Fellow at The Writers Institute, The CUNY Graduate Center. Her work has appeared in Granta,The New York Times and the anthologies And the World Changed (Feminist Press, 2008), 110 Stories. New York Writes After September 11 (NYU Press, 2002) and Leaving Home (Oxford University Press, 2001). She lives with her Darth Vader-infatuated five-year-old-son in Manhattan.