On a gray Saturday afternoon in Lima, Peru, this past April, I received a phone call from Hugo Blanco, veteran guerilla and survivor of multiple death sentences. “You wanted to talk?” he asked. “Come over now.” An hour later, after a ride through the city’s torturous streets, I was in the plaza in front of his house, an unpretentious single-level in a middle-class neighborhood north of the colonial center. I knocked and collected myself; I hadn’t actually expected him to respond to my request.

Blanco is a peer of the Marxist Latin American revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Che Guevara (he and Guevara were on opposite sides of a few debates). In the early 1960s, he organized peasant unions to seize land from feudal-style hacienda owners in the central Andean sierra. He was imprisoned for years by the Peruvian government, charged with the murder of a policeman who was killed during the struggles (Blanco has denied the charge). While in prison, he wrote Land or Death, a book that proposed how to build a communist insurgency on the back of land reform efforts in the Andes. His radical ideas earned him death threats from many quarters, and he spent years in exile in Chile, Sweden, and Mexico. In recent years, he’s been able to return to Peru.

What drew me to Blanco was not so much his insurgent past as his activist present. Spurred by the global environmental crisis and the encroachment of private industry on native-held land—a pattern that played out recently in the confrontations in the US at Standing Rock—Blanco has become an advocate for indigenous movements across the world.

Blanco grew up in the Cusco region of Peru, speaking the indigenous language, Quechua. In 2007, he founded the periodical Lucha Indígena (Indigenous Struggle), which covers the political and economic forces that conflict with indigenous groups. He continues to trumpet the successful ways in which indigenous communities have countered global neoliberal forces that threaten the environment. “The indigenous movement is in the vanguard,” Blanco told the journal Sin Permiso. “[I]t’s the most advanced sector in the struggle against the system and in the construction of an alternative organization of society.”

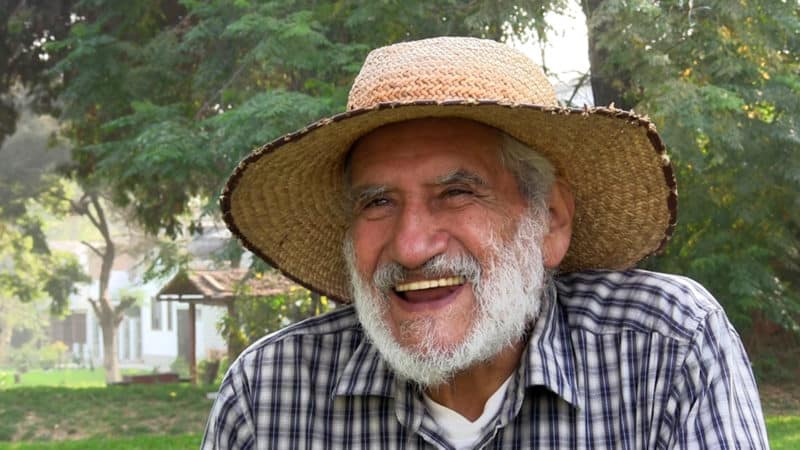

Now, at eighty-three years old, Blanco told me that he doesn’t get out much anymore, even though he had just returned from a month-long trip to Mexico to visit anti-mining activists. His home was sparsely decorated, filled with old books and magazines; his manner was low-key and inviting. We sat alone at his dining room table. In conversation, he is polite but direct, anchoring his ideas with anecdotes culled from years of travel and exile.

The era of Latin American Marxist insurgency may seem distant now, but Blanco sees connections to the issues of today. During our discussion, in Spanish, he spoke passionately about Trump, global warming, nature rights, and the significance of indigenous movements in today’s global political climate.

—Ted Hamilton for Guernica

Guernica: For years you’ve focused your efforts on wealth distribution and social justice. Why is climate change a pressing issue for you now?

Hugo Blanco: I’ve always fought for social equality. But now there’s a more important problem: the survival of my species. One hundred more years of rule by transnational companies and they’re going to exterminate the human species as they’ve exterminated other species.

The objective of these large transnational companies is to make the greatest amount of money possible in the shortest time possible. To this end they attack nature. They use technological and scientific advances with this objective, including in the United States, where fracking poisons the water that people have to drink. Governments, to a greater or lesser degree, also represent the interests of international companies. Even the progressive ones capitulate to them.

Guernica: You’ve said that indigenous groups can play an important role in combating global warming. How so?

Hugo Blanco: These days the attack on nature is strong, so there are more people defending ecosystems. And ecologists have respect for the indigenous because they defend nature, and give less importance to things like money. I’m a Quechua indigenous person, and we have a principle of love and the worship of nature, which in Quechua we call Pachamama, or Mother Nature. But there are indigenous people all over the world in Oceania, in Africa, in Asia, and in the north of Sweden and Finland. And the characteristics of indigenous peoples are that they have a great love for nature, solidarity, and collective rather than individual mandates.

For example, there is a story of an anthropologist who was working with indigenous children in South Africa. He put some candies and fruit in a tree and he told the children, “Run, and the first one to get there gets everything.” The children ran there holding hands and split everything among themselves. “Why are you so silly? I said the first one to get there gets everything.” And they answered him: “If there were one of us who was left without candy or fruit, we’d all suffer. I exist because you exist.”

The faculty members at a university in Cusco who study agronomy have learned that when they go to the agricultural fairs of the campesinos [peasants], they shouldn’t give prizes to the person who makes the biggest potato, or the largest quantity of potatoes, but instead to whomever produces the most varieties, because the indigenous think that’s more important. And when you ask, “What do you produce on your land?” they say, “Everything,” because they’ve got avocado next to the river, all the way up to the potato at the peaks.

There are certain mushrooms that only appear during the rainy season in Peru. And there was a campesina selling little mountains of them in the Cusco market. I told her, “I’ll buy all of them without asking for a discount,” which was a good deal for her, because usually you pay less for more quantity. But she told me, “No. If I sell you all of them, what am I going to sell everyone else?” Selling wasn’t just business, but a social relationship.

I cite these examples to show that there is something to being “indigenous.” Some people call us indigenous people “primitives,” and they’re right. Because we preserve the primitive organization that all of society once had, which is horizontal. They call us “savages,” and I think they’re right there, too, because the savage is the one who’s not domesticated. The condor is a wild animal, but the rooster is domesticated. I’d rather be a condor than a rooster.

Guernica: Is it possible to harness that type of collective power on an international scale?

Hugo Blanco: I’m for the idea that the global population self-governs. It’s the only salvation against global warming and against the destruction of nature. For that reason, indigenous peoples have more esteem than ever.

There is a philosophical principle that Marx got from Hegel. First is the affirmation, which is the thesis; then there’s the negation, which is the antithesis; then there’s the synthesis, which brings back the thesis and incorporates some of the elements of the antithesis. The thesis is primitive society: horizontal, not hierarchical. After came [the antithesis], civilization: caste systems, and in Europe vertical classes, led by those who command and who rule to their own benefit. And the synthesis is the resurrection of the thesis, or once again horizontal society, enriching it with some of the elements of the antithesis, or all the advances of society that have not put the survival of the species at risk. I think we need to arrive at this synthesis. And we’ll be there when all of society governs.

I don’t believe in leaders or caudillos [strongmen] or managers. But I think that what we need to push forward is the movement for collectivity. That’s what I believe in: power from below. And that organized society can be like that.

Guernica: Can you give me some examples?

Hugo Blanco: I’ve seen it in Limatambo, a district of campesinos near Cusco, in Mexico, and in Greece. In Limatambo, the campesinos asked, “Why are the mayors always the sons of the hacienda owners? Why can’t we nominate ourselves?” So they had a secret ballot, and they won their elections. But it wasn’t so that the individuals could govern. It was so that the community assemblies could govern. This is the mandate of the people, which is the same thing that the Zapatistas in Mexico have.

The Zapatistas have three levels of government: the community, the municipality, and the region. Many thousands of indigenous people govern themselves democratically with the principle of “lead by obeying.” The people choose a group of women and men as governors, but they don’t choose a president or a secretary general; all those chosen have the same rank. After a period of time they change out everyone, there’s no reelection, so everyone is at the head and there’s no indispensable person. When there’s a very important question, they convene a general assembly so that the collective decides. No authority at any level gets a cent. They’re like farmers and each gets their ration. Drugs and alcohol are forbidden. I don’t know if you would call this socialism, anarchism, or communitarianism. Nor does it interest me.

I liked what one comrade told me: “They elected me. If they’d elected me as a community manager, it wouldn’t have mattered, because then I could still cook for my husband and my kids. But they elected for the municipality. So what was I going to do? I had to travel. I had to teach my kids how to cook, and that was good, because now my sons’ wives can accept a post far away, and my sons know how to cook.” So they’re advancing.

We were there [with the Zapatistas] and they were explaining how they feed themselves, how they take care of themselves, how they’ve brought back indigenous knowledge. But they haven’t rejected Western medicine, so they’ve gathered surgeons and doctors from other areas who taught them how to build and operate a clinic. And they also accept not just Zapatistas, but partidistas [people affiliated with political parties]. But the partidistas have to pay for their medicine—the Zapatistas are treated completely for free. And recently a Zapatista told me, “Well, in the clinics there are more partidistas than Zapatistas—because since we feed ourselves well, we don’t get sick.”

There are also indigenous people in a town called Cherán, in Mexico, who chose to self-govern. One day, when there were municipal elections across Mexico, and parties came to do campaign propaganda in Cherán, the citizens said, No, we don’t want parties, we don’t accept any propaganda. And then they decided to elect somebody of their own choice, so they elected another governing council, also without general secretary or president who governed everything. And Mexican President Peña Nieto had to recognize them and say, “Well, since they’re an indigenous population, they have the right to follow their customs and traditions.” And so they have the municipal council, which has at its command the armed municipal guard protecting the frontier and the internal order.

In Greece, I’ve seen that in face of the government austerity, there’s a rise in activity from the base. For example, the government abandoned the state television channel and in Thessaloniki the workers took it in their power and they interviewed me. Later, because they were closing clinics, health workers—nurses and doctors—met up and made clinics. There is also a publishing house in the hands of its workers. There are many restaurants in Athens that are in the hands of their workers. There is a cooperative that receives goods from the countryside and sells them, avoiding intermediaries. And I told them, “You’re doing here in the city what the Zapatistas are doing in the countryside: creating power.”

So that’s it. The government of everyone. Not the government of one party, one person, or one leader.

Guernica: Are indigenous groups the only groups well-suited to fight capitalist interests?

Hugo Blanco: Of course not. You can see activism in the United States with the fight against the [Keystone] pipeline, where not just the indigenous but other defenders of the water came from all over the US. Of course, Trump has now ordered that they [build the pipeline]. But there is resistance. What’s more, I believe that the strongest part of the resistance has been the Women’s March. The greatest anti-Trump protest was the Women’s March. In Peru, the biggest march in the history of the country was the Ni Una Menos march in Lima, a women’s march. In Rosario, Argentina, there was a march of women. In Poland, too, they’re fighting for their right to abortion. I think that women are an important part of the vanguard now.

We’re constructing a new world here. Not only us, the fighters for social justice, but also those who work to produce ecological products, those who practice alternative medicine and alternative education, those who take over factories and become their own managers. All of them, too, are fighting for a new world.

Guernica: An Indian court recently recognized the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers as having legal rights. The rights of nature also appear in the constitutions of Ecuador and Bolivia, and they’re considered important by many indigenous groups. What do you think of the idea?

Hugo Blanco: We have to defend [nature rights] because we form part of nature.

The New Zealand authorities have taken an important step in the defense of nature and humanity, which should be followed by other governments. The Whanganui River [on the North Island of New Zealand] is now a “legal person,” and as such it has rights and obligations under a pioneering agreement signed by the New Zealand Parliament. This means that the river, which has been venerated by the Maori people for a long time, will have the same rights as a person. The Maori Whanganui tribe has been fighting for about 150 years for the river, the third-largest in the country, to be recognized as an ancestor—that is, a living entity. And now the parliament has finally approved a law that recognizes it as such.

Also, in 2014, Alberto Acosta [former minister of energy and mining in Ecuador] called for recognition of nature rights here in Lima. He said we’re not going to wait for the neoliberal governments to do this, because they’re never going to recognize them. And he organized a meeting for the defense of nature here in Lima.

Guernica: What are your hopes for indigenous groups in the coming years?

Hugo Blanco: There are indigenous struggles on all continents against the racist and colonial mentality and politics that defend the capitalist system. What’s been happening for twenty-three years in Chiapas, Mexico, in the Zapatista zone, makes me optimistic. I hear what the Zapatistas say: “Please don’t copy us. Everyone in their place and in their time will know how it’s done.”