The Ministry of Health recommends adopting the following handwashing technique:

Wet your hands with water.

Not many family members maintain the tombs of their loved ones in the Las Mercedes Cemetery in Dabeiba, a municipality of nearly 20,000 inhabitants tucked into a valley in northwest Colombia. Dirt and moss obscure the names on many of the tomb markers in the communal mausoleum. Dingy scabs of paint pull away from concrete walls. Mildew-speckled family mausoleums stand about like mangy dalmatians. Only the crosses shine blinding white in the midday sun.

It is December, 2019. A soldier stops cold as soon as he enters the cemetery. He is a witness for the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP, for its initials in Spanish), the centerpiece of the transitional justice system created by the 2016 Peace Accord, which ended five decades of war with the leftist FARC-EP guerrillas. Twelve years earlier, he dug graves in this cemetery to help his battalion disappear false positives: civilians, illegally executed by the army, registered as guerrillas killed in combat. When his battalion made their monthly quotas of neutralized enemies, the army rewarded them with promotions and days off.

It is not remorse that stops the soldier, but the position of the crosses. He talks with a gravedigger who confirms his suspicion: before, when his battalion used this cemetery to bury the evidence of their crimes, all the crosses faced south. According to the gravedigger, soldiers came to the cemetery around the time the JEP began hearing witness testimony and turned them all forty-five degrees. Now all the crosses face east.

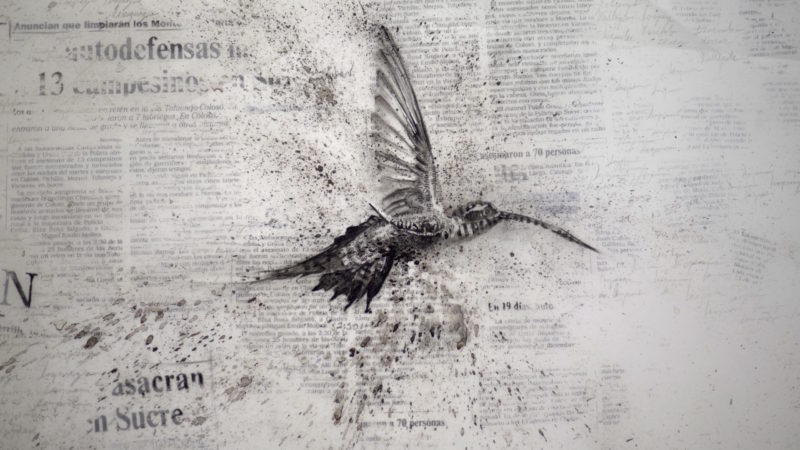

The gravedigger does not offer any information about the fresh paint on the crosses or about the strange fact noted in the news magazine Semana that all the names recorded on the grave markers seem to have been painted by the same hand, at the same time, even though the deaths vary by decades. In this graveyard, like most cemeteries in Colombia, anomalies abound. Partly, these places are disorganized. And partly, there are people who do not want it to be easy to find a body.

Apply enough soap to cover the entire surface of both hands.

Colombia has the dubious distinction of being the country with the longest-running civil war in the Western hemisphere. In 2016, the government signed a historic peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP), a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla army. The accord thus demobilized the largest revolutionary armed group active in the country, although its dissenters, and dozens of other armed groups, continue to operate. According to data collected by the National Center for Historical Memory, before its controversial takeover by Darío Acevedo, more than 4,000 massacres and 150,000 selective assassinations occurred between 1964, when the war began, and the report’s publication in July 2018. More than 262,000 people died and over 80,000 disappeared, a figure which surpasses the total number of people disappeared during the dictatorships in Chile, Argentina, and Guatemala combined. Of these, more than 68,000 are victims of forced disappearance: people abducted and assassinated by state agents, or groups acting with state support or acquiescence.

In a macabre game of hiding bodies in plain sight, cemeteries have been one of the principal burial grounds for victims of forced disappearance. Thanks to the truth commission created by the Peace Accord, we know the now defunct FARC-EP used official cemeteries in the towns of La Macarena and Granada, in Meta, while members of the armed forces and journalists have revealed that the Colombian government made use of a cemetery in Guayabetal, Cundinamarca and the Southern Cemetery in Bogotá. Taking advantage of the limited information exchange between municipalities, paramilitaries have dumped bodies in fields and along highways far from the victims’ homes, expecting that abandoned bodies would be buried as John and Jane Does in nearby graveyards.

The Peace Accord represents a legally binding promise to unearth these bodies and with them, many truths about the war. Since 2018, when President Iván Duque was elected, however, implementation of the historic agreement has dwindled. His party has repeatedly denied a civil war or armed conflict even exists, claiming instead that the problem is terrorism directed at the state, casting the government as the true victim and subordinating civilian victims to minor roles while erasing victims of state violence all together.

It is estimated by the Colectivo Sociojurídico Orlando Fals Borda that as many as 40 percent of the bodies of victims of forced disappearance may be found in official cemeteries; the rest, it is believed, lie in unmarked graves. The location, discovery, and identification of these victims is challenging even under the best circumstances. The task is made even more difficult when individuals go into cemeteries and make unorthodox, unauthorized changes, like reorienting or repainting grave markers.

Rub the palms of your hands together.

It is not the wake Édison Lexánder Lezcano’s family imagined. Instead of mourning in the privacy of their home, they are in the town’s central plaza. Instead of the bereaved being limited to family and friends, the entire town is there, along with magistrates from the JEP, officials from the Investigation and Prosecution Unit, forensic scientists, and representatives from the French and Swiss Embassies. And instead of praying over a coffin the size of a twenty-three-year-old man, the JEP presents the family with a child-sized coffin, about one meter long. Bones, especially when broken, take up less space.

It is 2020, eighteen years after Édison Lexánder Lezcano was kidnapped, murdered, and disappeared by a mixed group of soldiers and paramilitaries. Édison’s is the first body identified of the seventeen discovered so far in the mass grave in the Las Mercedes Cemetery, and the JEP has delivered his body to his family for burial, which has suddenly become a very public affair.

Three days later, his family arrives at the church for Édison’s memorial mass. At least this part of their farewell, they think, will be just as they imagined it. But when they walk inside, they find a funeral wreath addressed to the National Army, a Galil rifle, a military backpack surrounded by trench sandbags, and a jungle ghillie suit, all displayed at the altar where they planned to pray for Édison. According to independent news outlet Noticias Uno, just that morning, a soldier had requested a memorial mass in honor of four soldiers who died in a mined field in Dabeiba fifteen years earlier.

It could be a coincidence. But how often does the army hold memorial masses in honor of four low-ranking soldiers who died so many years ago, when hundreds die in combat every year? And how often do they crowd the altar with symbols of war?

Rub your right palm over the back of your left hand,

interlacing your fingers. Switch and repeat.

As in many countries, cemetery space is prime real estate in Colombia. Grave or tomb plots are rented and when the family can no longer make payments, the remains are exhumed and cremated so another body can occupy the plot. The estimated 25,000 unidentified cadavers the civil war has produced over the decades create a problem for graveyards. Before 2010, unidentified remains were often buried in collective graves in official cemeteries without documentation, making it difficult for families of victims of forced disappearance to locate their loved ones. Laws passed in 2010 and 2015 changed this, requiring such remains to be buried in individual graves or tombs marked with any information available about the deceased. But given the premium on space, cemeteries often exhume unidentified remains after a few years and store them in boxes or bags.

On April 3, just when the JEP and Disappeared Persons Search Unit (UBPD, for its initials in Spanish) finally began to make progress on the location and identification of some victims of forced disappearance, the Office of the Inspector General of the Nation issued a proclamation. Due to the anticipated increase in deaths owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, the state agency ordered cemeteries to bury all unidentified bodies, in defiance of both the law and the gravediggers’ ability to bury the dead.

The proclamation provoked indignation and protest. Seventy-two national and international human rights and victims’ organizations denounced the order, pointing out that the bodies of many victims still awaiting identification in graveyards are in danger of being disappeared anew. In fact, their disappearance is practically guaranteed. The pandemic is convenient. Now, the authorities do not have to send soldiers into cemeteries to disrupt the graves in order to make the truth more difficult to discover.

Grab your left thumb in your right palm

and rotate it back and forth. Switch and repeat.

On March 24, the country entered a mandatory nation-wide quarantine. Strictly enforced restrictions on movement, including a prohibition on inter-municipal travel, confined most people to their homes. In a country already divided by its challenging geography, the state response to the pandemic made the most vulnerable citizens even more isolated, which in turn made those who threatened the status quo easier to silence. Death threats and assassinations of community activists began to increase almost immediately. According to Indepaz, a research organization focused on peace and development, 310 activists were killed in 2020.

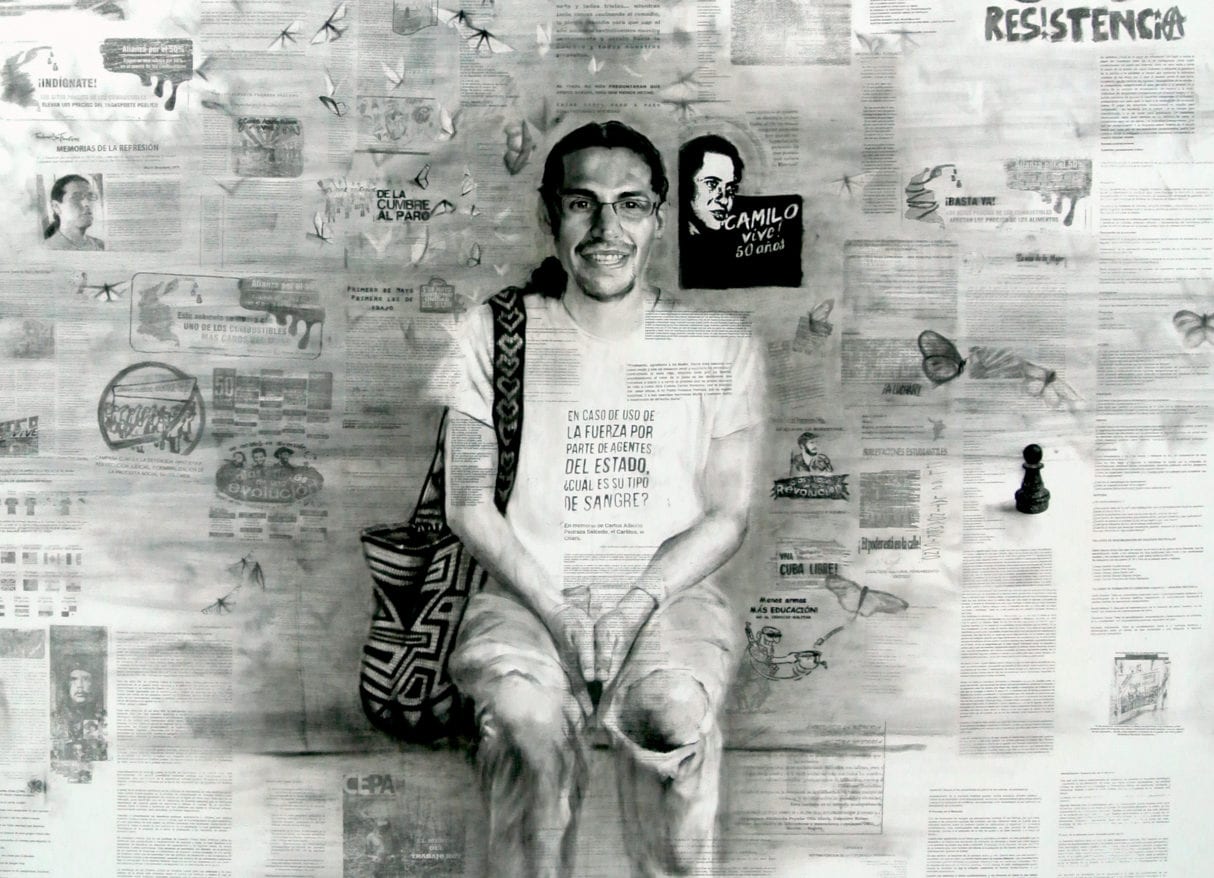

These murders have received substantial national and international media attention, but news outlets have been silent on forced disappearance, a crime whose trauma has a broader reach. Characterized by uncertainty, both about exactly what happened to a loved one and who is responsible, forced disappearance subjects a community to years of unremitting stress. This makes it a highly effective tool of repression and social control. According to Erik Arellana Bautista of Human Rights Everywhere, an association of investigators and journalists dedicated to documenting this crime, approximately two hundred people were officially registered as victims of forced disappearance in 2020. Since fear prevents many family members from reporting a forced disappearance, this number is doubtless too low.

Indigenous communities in places where extractive industries are present are at high risk of forced disappearance. In the Amazon, where illegal deforestation has increased exponentially since the pandemic began, many Nukak Maku activists fighting to defend their reservation territory and recover lands usurped by logging companies have been forcibly disappeared. Other community members have been violently displaced, sometimes driven from their reservation altogether.

For years, Senators Iván Cepeda and Roy Barreras (among others) have been pushing for the government to take some definitive action to stop the violence against activists. On May 15, the Colombian Congress debated and passed a law, spearheaded by the president’s party, to declare the carriel, a traditional leather bag, Patrimony of the Nation. In a tweet that afternoon, Congressman Juan Espinal expressed his gratitude for “such an important law.” On the same day, Javier García Guaguarabe, an indigenous guard of the Embera reservation and community activist, was murdered.

Rinse your hands with water.

The families of victims of forced disappearance could not go out into the streets, as they have for ten years, to honor their missing for the International Week of the Detained and Disappeared in June. Many of them made altars at home instead, sharing photos of their private memorials on social networks with the hashtags #MemoriaEnCasa (“MemoryAtHome”) and #DóndeEstán (“WhereAreThey”). Signing onto a campaign created by the Disappeared Persons Search Unit (UBPD), others recorded videos of them speaking to their disappeared loved ones, telling a little of what it has been like for them to live all these years without them. While Colombians who have the privilege of deciding whether they want to think about the war complained of not being able to hug their friends, the UBPD posted a series of memes expressing what it is like for a person searching for their disappeared. “During this time without you,” says one, “I’ve found strength in the hugs of others who also share my pain.”

Poet Juan Manuel Roca has written that in Colombia, the truth has an expiration date, one that varies according to the victimizer’s power to deny not only their involvement in but even the existence of a crime. There is no armed conflict, no war, according to President Duque and his Democratic Center party, and therefore no crime. As former president and ruling party leader Álvaro Uribe has told family members of victims, the murdered and disappeared were not just out in the fields picking coffee beans. In other words, there must be a good reason they were killed. In other words, they are not victims, but terrorists. In other words, in this country of massive inequality, monopolization of land and resources, and racism, there exist only upstanding citizens who defend family, tradition, and property, and terrorists who seek to destroy these values. According to this logic, the author of this essay is herself a terrorist.

Colombia’s history, says Roca, is written not with the pencil’s point but with its eraser. While the cemeteries fill with victims of both disease and war, those holding the pencils are scribbling away, writing even more blank pages into the already thin history books.