I have spent my entire academic career analyzing images of enslaved people, with a particular interest in their dress. This research led me to found a digital humanities project called “Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom”, which uses fashion to explore the creative ingenuity of people of African descent. Yet, I often know frustratingly little about the lives and identities of the individuals who populate the project’s Facebook and Instagram feeds. The experiences of enslaved people were not always deemed important enough to record for posterity, and the glimpses that have been preserved are often distorted by interventions of enslavers. We are left to wonder: Who are they? What were their names? What were their favorite colors? Why did they choose to be photographed on these particular occasions? Why did they style themselves in these ways?

One thing we do know is that incorporating black people into fashion history can disrupt easy narratives, including that of the gradual progression from one silhouette to the next. Traditional fashion history is often organized by the reign of European monarchs, which, in the case of the Anglophone academy, often means the British. Georgian round gowns give way to Victorian hoop petticoats that then begat Edwardian walking skirts, and so on. But enslaved people and their descendants do not fit neatly into those fashion timelines, often by their own choosing. Hattie Thompson, who was born enslaved, insisted that “patching and darning was stylish” when she was a child, even though the dominant style in the late 1850 and 1860s would have consisted of Victorian gowns and suiting—styles that certainly did not use a patchwork aesthetic or darned fabrics.

Sometimes, the only information about enslaved people can be gleaned from photographs: a sly smile, the cock of a hat with panache, dapper suiting styled with individual flair. There is no shortage of images of enslaved people and their descendants dressing on trend. In many archives around the world–my favorite being the Library of Congress–there are digitized photographs of enslaved people and their descendants decked out in their finest Victorian and Edwardian attire. Black contributions to fashion history are hiding in plain sight; it is just that many scholars and curators have not, until recently, taken an interest.

Enslaved people and their descendants had and continue to have a fraught relationship with the fashion system, a term coined by “Roland Barthes”, that encompasses the production, consumption, and preservation of fashion items. Black people continue to be disrespected and ignored by the fashion world, an attitude reflected in fashion magazines and museum collections. Though black models and designers are starting to become more commonplace in fashion media, these acts of inclusivity amount to nothing less than woke-washing if black people’s contributions to the entirety of fashion history continue to be ignored. The genesis of the fashion industry lies in the unpaid labor of enslaved people who cultivated the raw materials to make textiles and helped to manufacture garments. At the same time, enslaved people also consumed fashion items, and, in the process, became trendsetters.

*

The very definition of fashion is attached to time. To dress fashionably is to style oneself with contemporary and future sartorial references in mind, even if that means subverting and ignoring those temporalities. While people of African descent dressed according to the trends of their time, they did not always concern themselves with white observers’ approval of their self-presentation. Due to the limited resources they had in styling themselves, enslaved people often used ingenious details in their clothing that did not fit neatly into white-dominated fashion histories.

Charlotte, for example, was “a seamstress for Martha Washington at Mount Vernon”. In her position, she may have developed a taste for elite fashion and acquired her own fashionable attire through second-hand clothing markets. On one of her Sundays off, Charlotte traveled to nearby Alexandria, Virginia, where she crossed paths with a Mrs. Charles MacIver, who believed Charlotte was wearing a dress that she had once owned. According to Mrs. MacIver’s husband Charles, the dress was “altered for the worse, particularly in the Flouncing which went all round the Tail. The Lining originally overshot the Chintz at the Sleeves, which used to be concealed by Cuffs, as they were very short. I understand the Boarder is turned upside down.” The alterations were an affront to Mrs. MacIver’s sartorial sensibilities, but spoke to Charlotte’s taste and preferences.

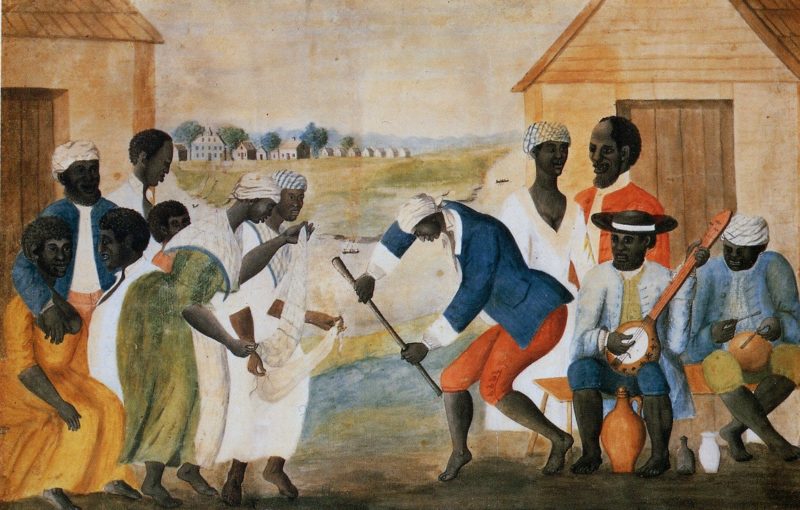

Rather than abandoning their aesthetic values, enslaved people subverted European fads and even led the way in setting new trends, often by mixing dress practices from different cultures like European suiting, old military uniforms, and African-origin headwraps and jewelry. For example, one of Marie Antoinette’s favorite ensembles was the gaulle (later called chemise à la reine), a white muslin shift that her dressmaker Rose Bertin adopted from white Creole women who, in turn, adopted it from women of color in the Caribbean Basin and West Africa. In this way, black women not only participated in the larger fashion system, but also shaped it, often without credit or attribution. Items like the robe chemise, selective use of madras, and, in some cases, headwraps were appropriated from black women by white women in Europe and North America—a precursor to what we might call cultural appropriation today.

Additional to this patchwork aesthetic, enslaved people also had a penchant for discordantly bright colors and prints in the eyes of white onlookers. This supposedly incongruent styling lives on in the “matchy-matchy” aesthetic of African Americans, which opposes larger (white) dominant norms or taste and ideas of “color blocking”.

*

Last year’s hallmark exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute, Camp: Notes on Fashion, focused on the work of high-end American and European designers of the 20th and 21st centuries. The tongue-in-cheek self-fashioning of people of African descent was largely excluded, even though enslaved peoples and their descendants were some of the most persistent purveyors of what would become known as “camp.” In their exclusion from mainstream white society, they appropriated the trappings of the dominant class, subverted their meaning, and ultimately stripped them of their power. For example, during holidays like Negro Election Day, Pinkster, Jonkonnu, and Carnival, enslaved people donned the dress of elites and wore masks approximating the skin and hair of white people, a symbolic inversion of the class and racial hierarchy of slave societies.

Diversity isn’t simply about adding black people and stirring. It involves changing the way scholars and the public view fashion history, revising fashion museums’ permanent collections, and adopting a more expansive view of who produces and consumes fashion. Considering fashion history in its full complexity is an entry point into understanding people’s day-to-day experiences; everyone wears clothing for both utilitarian and decorative purposes, and there is a lot of information embedded in dress practices. Yet, many are not accustomed to thinking about what they wear through a critical lens. The majority of the people who view the Met’s exhibition do not have the time, privilege, or access to a wide array of fashion scholarship, and visiting exhibits like Camp and About Time: Fashion and Duration is the extent of their engagement with fashion history. The Met, host to arguably the most visible fashion exhibits in the world, has the power to transform the way the general public understands fashion history, yet it continues to repeat narratives established by white-dominated institutions and scholarship.

One obstacle cultural institutions face in incorporating slavery into fashion histories is that most enslaved people wore practical and unfashionable clothing made from coarser textiles, which rarely survive in museum collections today. Though enslaved people acquired a handful of fashionable garments that were reserved for Sundays, weddings, and other special occasions, their workaday clothing was more utilitarian and, thus, not deemed worthy of preservation. Curators do not read the silences in collections; rather, they rely on what’s preserved in lieu of thinking more creatively about ways of examining the dress practices of those whose clothing may not have been collected. Moreover, they impose order through their classificatory gaze and scholarly expertise to a fundamentally disorderly fashion system that was, in part, dictated by economic limitations and individual choice—even by those who had the least agency in society, like enslaved people. Take, for example, Fanny Kemble’s description of enslaved people in their Sunday best:

Their [the negro] Sabbath toilet really presents the most ludicrous combination of incongruities that you can conceive—frills, flounces, ribbands, combs stuck in their woolly heads, as if they held up any portion of the stiff and ungovernable hair, filthy finery, every colour in the rainbow, and the deepest possible shades blended in fierce companionship round one dusky visage, head handkerchiefs, that put one’s very eyes out from a mile off, chintzes with sprawling patterns, that might be seen if the clouds were printed with them—beads, bugles, flaring sashes, and above all, little fanciful aprons, which finish these incongruous toilets with a sort of airy grace, which I assure you is perfectly indescribable.

Keeping the above women in mind, it is nearly impossible for curators to include contributions of enslaved people in fashion exhibitions if they continue using the same modes of classification and scholarly expertise emanating from Eurocentric fashion capitals, which are more moneyed, better documented, and more easily conformed to linear fashion histories. Museums may not contain fashion items worn or created by enslaved people–and, if they do, they are often too fragile to display–but they can recreate exemplars using archival images and textual descriptions. More broadly, fashion scholars and curators need to start thinking more inclusively about the meaning of fashion and the fashion system, explore new scholarship on diverse communities, and invite more creatives and thinkers from those communities into their institutions in permanent capacities.

Camp was a missed opportunity to showcase people of African descent’s tongue-in-cheek self-styling, an aesthetic that is ultimately a political statement that questions inequality and attempts to upend racial hierarchies. About Time could have pushed forward conversations about the black innovations that date from the genesis of the fashion system, if not before. Sagging pants, over-the-top church hats, and zoot suits are just a few out of a long list of examples of black sartorial genius. Since launching Fashioning the Self in Slavery and Freedom, I post an illustrative image almost every day, and I have yet to run out of content. The genius of black fashion is an endless font, and the fashion establishment should acknowledge the contributions of enslaved people to the birth of the fashion system.