John Ashbery is something of a rock star to poetry lovers. The man himself is genial and approachable; the poetry, however, has a bad-boy appeal: difficult, magnetic, rebellious. Last spring, he read from his latest collection, A Worldly Country, at St. Mark’s Church in Greenwich Village. He walked to the podium in the body of an eighty-year-old man; yet the voice that emerged was much younger. He thanked his introducer, Anselm Berrigan, who referenced Ashbery’s early dismissal (age eight) of rhyming poetry. Ashbery laughed a little at that youthful renunciation and then read A Worldly Country‘s title poem, composed entirely of rhyming couplets: “One minute we were up to our necks in rebelliousness, / and the next, peace had subdued the ranks of hellishness.” It seemed to be a gesture to a defiant past put behind him, but no one was fooled.

A descendant of T.S. Eliot, another poet who broke with literary convention and enjoyed an uneasy relationship with his birth country, Ashbery was born in Rochester, New York, in 1927. He grew up on his father’s fruit farm, a place poet Dan Chiasson recently referred to as the kind where imagination is the only escape from boredom. After graduating from high school, Ashbery went to Harvard where he befriended Frank O’Hara and Kenneth Koch. He later received his M.A. from Columbia. When he was twenty-eight, Ashbery’s first book, Some Trees, was selected by W. H. Auden for the 1956 Yale Series of Younger Poets Award, and the same year he also received a Fulbright and moved to Paris where he remained for a decade. After his scholarship money ran out, he survived by translating and writing art criticism for the International Herald Tribune. Ashbery’s real success came in 1975 when Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Ashbery has published more than twenty poetry collections as well as prose, plays, and one novel co-written with James Schuyler. He is the Charles P. Stevenson, Jr., Professor of Languages and Literature at Bard College and divides his time between New York City and Hudson, New York.

A Worldly Country continues Ashbery’s tradition of discursive poems, akin to Eliot as much as to the French poets Ashbery admires. Frequently he uses pop references in his work, and while he isn’t entirely dismissive of American culture, he admits, “I’ve always felt somewhat at a remove from the world around me in America.” That remove, of course, may be mirrored back to him by readers who are baffled by his poems, one who famously wrote in to the New Yorker, a magazine that had frequently published Ashbery’s poems, to profess his utter confusion. Along with the advice Ashbery himself offers below to those readers, another might be simply: attend a reading. It’s not that Ashbery is a performer; rather, it’s that the poems are meant to be heard. Tuning in and out of an Ashbery poem heightens the experience, allows you to savor a particular line or phrase. In a word: music.

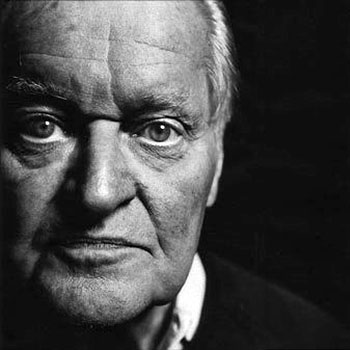

At eighty, Ashbery is active as ever: in addition to A Worldly Country, he released his selected later poems, Notes from the Air, late last year. This collection is a far cry from a swan song. Ashbery continues to write new poems, was just appointed Poet Laureate of MtvU (MTV’s college network) and is looking forward to an upcoming collaboration with filmmaker Guy Maddin. Often when the age of a poet is mentioned, the number is a kind of excuse, a polite way of acknowledging a writer’s falling off. Ashbery’s face has some telltale signs of age: a little slack in the cheeks, a few deep-set wrinkles in the forehead. But he is far from ravaged, and his age would be difficult to guess. In photographs, he often gazes directly at the camera—tight-lipped as if he is keeping secrets. He has the same square jaw of youth, the same thin lips and clear, blue eyes. The part of his hair is the same, though the locks have thinned and whitened. And his poetry too is as beguiling as ever. Like Merlin, he seems, almost, to be aging backwards. More than any other American poetry, Ashbery’s lends itself to subjective interpretation, and I have no qualms about reading myself into “To Be Affronted” from A Worldly Country: “When I was young I / thought he was a wizard.”

—Erica Wright for Guernica

Guernica: Your appointment as MtvU’s Poet Laureate calls up all kinds of fun stuff about the intersection between pop and high art.

John Ashbery: Well, there’s a lot of pop in my poetry, so it seems appropriate. A lot of my poetry comes out of popular American culture like comic strips and B movies and song titles and stuff like that.

Guernica: You do use a lot of American pop culture. At the same time, in a 2005 interview for the Guardian you mentioned that you feel like a foreigner in America.

John Ashbery: Well, I’ve always felt that way, even as a child, I guess because my interests, in poetry in particular, are not those of most Americans, and yet I continue to have them and to also be interested in the things that other Americans are interested in. But I’ve always felt somewhat at a remove from the world around me in America.

I feel that I have more company among other estranged people.

Guernica: From the poetic world or the world in general?

John Ashbery: From the world in general. When I was very young, I read Thomas Mann’s novella “Tonio Kruger” and identified very much with the hero of that, who looks into the houses of bourgeois families at night and realizes how estranged he feels and how much he would like to join that world, but can’t.

Guernica: Hm. Do you still feel estranged?

John Ashbery: I don’t feel less estranged. I just feel that I have more company among other estranged people. [laughing]

Guernica: In a recent poetry interview on this site, Robert Pinsky says he hates poetry that is “dumbed down.” In an earlier interview with Billy Collins, Collins emphasizes almost the opposite stance, criticizing difficult poetry as self-indulgent and perhaps hiding something. Is either of them right? Are they both right? What do you say to someone who tells you that many readers are just used to a more linear thought process than your poems convey?

John Ashbery: I guess I would have to side with Pinsky. I came of age in the mid-twentieth century when modernism was at its height. It was more or less expected that great literature (Joyce, Pound, Proust, Stein) would be hard to read, and people seemed actually to look forward to that. I remember how excited I was when my tutor at Harvard assigned me James’s Wings of the Dove, perhaps his most difficult book. My feeling was, “Gosh, this is really hard to read, but I’m sure I’ll have learned something by the time I finish.” And I did. Though it would be impossible to summarize in a few sentences. Somehow the word “accessible” never turned up in discussions of poetry in that era.

Guernica: I should point out that one of two “difficult” poets Collins praised was you. But along with learning something, as you say, what other rewards await the readers of so-called non-linear poetry?

John Ashbery: I hope that there is an element of surprise in my poetry and that it’s a pleasant one. Again, the reward for “reading so-called nonlinear poetry” must be to learn something new or find oneself in a different place.

Guernica: I was struck by the title of your latest selection of poems, Notes from the Air. “Notes” more than “Air.” I’m thinking of the Symbolist notion of all poetry aspiring to music.

John Ashbery: I wasn’t thinking of musical notes so much as taking notes.

Guernica: Well, what about the relationship between music and poetry? That there is such a relationship seems especially apt for your poems.

John Ashbery: For me there is. I listen to music a great deal. In a way, it’s trying to express things that can’t be expressed in words. That’s something that interests me, too. Even though I use words to express myself, I am trying to, it seems to me, get beyond that.

Guernica: Can someone, say a student who’s resistant to your work, be taught how to read you? Is it an issue of negative capability?

John Ashbery: I don’t think a student who is resistant to my work ought to be taught how to read it. It’s best if he or she tries to live with it a while, leaves it, comes back to it, leaves it again, etc. That’s how I first read modernist poetry. And yes, negative capability is certainly a valuable asset.

Guernica: Do you think criticism published about your work is useful? Harold Bloom’s 1985 collection, for example.

John Ashbery: Yes, I think it will lead them to the poetry. If it never were written about, no one would know anything about it.

Guernica: You’re often claimed by various schools, most commonly the New York School, but also, for example, the Language Poets. Do you think this branding of schools is useful, or dangerous?

John Ashbery: I think both. In a kind of crude way, it indicates the sector of the poetry landscape one occupies; but on the other hand, as with all labels, it’s inexact and can be really misleading. I never invented the term “New York School,” and in fact, none of the other poets did either. It was kind of hoisted on us by the art dealer who published our first small poetry pamphlets, so that’s how we became known. Other literary movements like Language Poets and Surrealists have chosen their name and use it as a kind of banner. But in our case, it was sort of an accident. Although it’s convenient to know that we were all in New York at one time and all in a larger sense experimented with language, that’s about as far as it goes. I think that the differences among us are actually quite broad and don’t really contribute to the notion of a school.

A good poem makes me want to be active on as many fronts as possible.

Guernica: Wasn’t the brand “New York School” partly a marketing tool?

John Ashbery: Yes, and in fact John Bernard Myers, who was the founder of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, wrote an article in 1961 about the New York School of poets. Since the New York School of abstract expressionist painters was so influential and important, I think he intended that some of it would rub off on his small circle of poets. You’re right; that was sort of the connection.

Guernica: How do you think of your writing as experiment, which you mentioned earlier? There never seems to be a particular procedure involved unless you’re working with a form like the pantoum or the sestina.

John Ashbery: Well, the pantoum or the sestina, which we all use occasionally, are forms which take the poem really out of the hands of the poet in attempting to satisfy the constraints that are the trademark of these forms. Therefore one can allow one’s unconscious mind to go about forming the poem in a way that is even more effective than what the Surrealists practice, called “unconscious writing,” which I don’t think ever gets that far from consciousness. Having to accomplish a task that is almost mechanical is a far more effective way of liberating one’s unconscious mind to write the poem. That’s only one small example, though. In general, I think we intended to avoid the classical norms that were dominant in poetry. When we were in college, for instance, we were kind of rebelling against the academic climate by any means that we could.

Guernica: Do you mean you were rebelling against the generation directly before you: Lowell, Hughes, and Berryman?

John Ashbery: Yes. Kenneth Koch’s poem “Fresh Air” is actually a kind of manifesto we all subscribed to. It talks about a Poetry Society where academic poetry is formulated that is disrupted by a kind of Batman-like figure called the Strangler, the enemy of bad poetry. I suggest you might take a look at it. One line in particular—someone gets up at the Poetry Society to read a poem that begins, “This Connecticut landscape would have pleased Vermeer,” and the Strangler immediately strikes that line down.

Guernica: Some of your early critics complained about your lack of political writing.

John Ashbery: My feeling is that most political poetry is preaching to the choir, and that the people who are going to make the political changes in our lives are not the people who read poetry, unfortunately. Poetry not specifically aimed at political revolution, though, is beneficial in moving people toward that kind of action, as well as other kinds of action. A good poem makes me want to be active on as many fronts as possible.

Guernica: Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

At that point, I kind of questioned myself: if no one is ever going to read it, should I go on writing it?

John Ashbery: Political poetry seldom achieves its goal since the people who should read it (presidents, politicians) don’t read poetry, and most of those who do are already persuaded of the truth of its messages (war is bad, government and industry are often corrupt, racism and other kinds of discrimination should be abolished, global warming is destroying the world, etc.) and might be annoyed at being lectured for wanting ideals they in fact possess. Non-didactic poetry, which seeks merely to delight (Keats’s sonnet about the grasshopper is a good example) can inspire readers to act humanely on many different levels, including the political one.

Guernica: Was it useful for you to know Kenneth Koch, Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler—other young poets, I mean.

John Ashbery: Oh yes. When we were young, we were our only audience. We would write poems and read them to each other, and in fact, for quite a few years, I didn’t really think that anybody else was going to be interested. My first book was not at all successful. I’m talking about the Yale University one, which I think they printed 800 copies of, and it took eight years to run out. And the second one got universally panned. At that point, I kind of questioned myself: if no one is ever going to read it, should I go on writing it? Shouldn’t I do something that will affect people, some other form of art perhaps? I can’t say that I ever thought this out in any detailed form, but I perhaps gradually realized that this is what I enjoy doing most, and I was going to go on doing it. And perhaps someday somebody would like it.

Guernica: And, of course, they did.

John Ashbery: Yes, strangely. [laughing]

Guernica: Is it true that Auden picked your first book on the fly? There’s the story that Auden had to pick a winner or he wouldn’t be paid.

John Ashbery: What happened was both Frank O’Hara and I submitted to the Yale competition, and we had our books returned by the press. Even though we knew Auden, according to the rules, we couldn’t send our work directly to him. Apparently he decided not to publish any of the manuscripts that had been forwarded to him. Later on, his friend Chester Kallman told him about me and O’Hara, that we’d had our manuscripts returned, and he asked to see them. (He was spending his summer in Italy.) So we sent them to him, and he chose mine. It was only recently that I discovered, in reading the letters of James Schuyler, that apparently Auden wasn’t very enthusiastic about mine either, but he wouldn’t get paid if he didn’t publish something that year. On the other hand, he’d already refused all the other manuscripts, so he must have had some liking for mine. [But] I don’t think he really understood my poetry very much. In fact, in later life, I heard that he said to somebody that he’d never understood a line of it. On the other hand, he was a great influence on me. In my youth, he was the first modern poet I fell in love with and read with understanding. I think he had a big influence on my early work, but I understand that it would be invisible to him. That’s just the way these things happen, it seems to me. Perhaps there was some echo of him that he found in my poetry after all.

Guernica: What’s next for you, following such a momentous year?

John Ashbery: I continue to write poetry, and I wait until it seems like there’s enough to make a book, and then I put it all together and send it out. I’m looking forward to working with the filmmaker Guy Maddin. We’re planning a kind of collaboration of some kind. We don’t really know what, yet. He’s been very occupied this year with a film that just came out and was at the Toronto Film Festival, a sort of documentary—I guess you could call it, though it was certainly a very strange one—about Winnipeg, which is the city where he was born and has always lived. He sent me the DVD of it, and it’s a terrific film. I don’t really know what we have in mind, yet. We haven’t gotten around to discussing it because he was working on this other film. But he’s someone whose work I had admired for about ten years, and I didn’t realize that he was also a fan of my poetry at the same time until we met last year in New York and hit it off instantly. And then [we met] again this year when I read a sort of narration at a public performance of his, Brand Upon the Brain!, which was done in New York, behind St. Mark’s on Second Avenue. He had an orchestra, a Foley sound effects artist, a singer, and I was also reading a text. Anyway, now it’s onto discover what it is we’re going to do together. It will certainly be untraditional if he has anything to do with it. He usually writes his scripts himself, so I’m not quite clear what my role will be, but we’ll find that out.