1

This was always a possibility, I thought, carrying the lightweight urn.

This was always a possibility.

We talked about this situation now and then. It’s not a pleasant topic of conversation, but it was something we needed to work through. A task that came to us, as we drank tea together, ate meals together, held hands, touched lips, inscribed each other’s names on our bodies. There were many things besides love that we had to consider. We accepted that reality and enrolled in the Corporation’s mental health program. I prepared for my death; G prepared for a long wait.

We did simulations. With my age always the same, I met G aged fifty, sixty, seventy. G held my funeral. I can vividly recall G at seventy. G was gardening when I showed up. I knocked on the unfamiliar front door, and an older G opened it with an expression of joy and slight confusion. I handed G a copy of the Corporation manual, Life as a Space Pilot’s Next of Kin: Caduceus Takes Care of You. Standing there, G opened it to the “Partner” section, read it, and then nodded. Crying, G stepped toward me with open arms. I was held, still, in G’s embrace. Back at home that night, I clung to the real G. The smell of G’s body had been missing from the simulation.

When I mentioned this, G smiled. “Well, that’s a tricky one. Maybe one of the simulations will end with you taking off again because you don’t like my old-person smell.”

Touching that smooth face, running my hands across that familiar body, I murmured, “I’m sure it’s not important. If it’s not there, it can’t matter.”

In the simulation, the door to our house was blue. Blue meant Sector 27, one of the residential areas of Makiyende. I’d never been to Sector 27, a place for retired space travellers. A place for people out of step with the current era. Before meeting that simulated blue door, before meeting G, I was only able to bring to mind the door of the place where I used to live alone. And it remained in my memory, just barely, as a vague impression. If that day does come, when I go to Sector 27, surely G will be waiting there for me. So it’s all alright. I reached for G’s hand and held it tight. G squeezed my hand too, with comforting force. You’re my home.

I don’t really know what G saw in the simulation. The Corporation’s mental health program shows the patient their most likely state of crisis, according to whatever situation they’re in, and prepares them for it. G said almost nothing about the simulation, but right after the first session signed up for the optional counseling program. In my simulations, G was always there. In G’s, I was probably gone. Even though we never went into the simulation together, working as a space pilot, it was easy enough to guess that much.

G once said, “If things do turn out that way, I want to see you again. Even if it’s just your remains.”

Although I didn’t know what G had seen in the simulation, I couldn’t say such a sad thing would never happen. Because it would be a lie. I didn’t tell G that the Corporation hardly ever brings back the corpses of employees who’ve died in space; that they just collect them up for a while then thrust a batch out through an atmosphere to incinerate them. It wasn’t exactly a secret, but I didn’t think the disposal process would be explained in detail in Life as a Space Pilot’s Next of Kin: Caduceus Takes Care of You. Still, the Corporation always sent whatever items the pilot designated to their designated person, without fail. The Corporation keeps its promises. It just never promised to bring back pilots’ remains. Pilots usually choose to designate things that aren’t kept on their person. I chose an album with all the photos of me and G that I’d gathered, and my Flying School graduation medal. I always thought G had decided to make a much bigger sacrifice than me and had greater resolve. So I didn’t go out of my way to talk about any of that. Just in case an extra nugget of information would make the emotional load too heavy to bear, in case one more thing might break the back of G’s resolve.

We did our best to prepare, but for the opposite things.

2

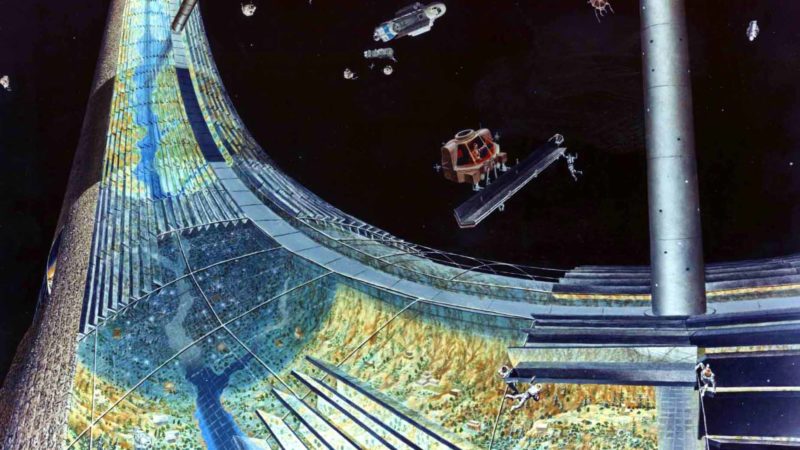

Making spaceships isn’t part of the shipbuilding industry; it’s a sector of the construction industry. Like constructing a town on the surface of a planet, building a spaceship creates a residential area that flies through space. Caduceus Corporation builds spaceships like they are building homes. Efficiently, meticulously, and beautifully. To be perfect. G built homes that move.

“What a fresh idea. To call it construction, rather than shipbuilding.”

G pulled a face of disbelief: “It’s just common sense! Everyone knows the construction industry and spaceship-building industries are one and the same. What did you think you were piloting around? A hopped-up car?”

“A spaceship.”

“Ha ha, very funny.”

“No, really—however I look at it, I’ve never thought of my work as flying a home.”

“But you went through so much to become a pilot. Aside from a home, is there anything else worth going through all that to fly?”

“How romantic,” I gasped, genuinely moved.

G examined my face a while, then said with a frown, “I still don’t really understand what gets you all misty-eyed.”

“The universe. Spaceships. Flying.”

“I know that much.”

“And you.”

“Right, me. I know that too.”

I didn’t say anything more, just pulled G into an embrace, smiling from ear to ear.

On my next flight, I piloted a midsize passenger vessel. It was a short flight, taking employees who were emigrating, passing through a space jump acceleration portal near the capital. I imagined that I was steering a vast home, made up of many smaller homes: all the passengers’ cabins. Whenever I went back to my quarters to sleep, I thought of myself as returning home. It was a really beautiful experience. Sitting alone in space, I felt so grateful to G for making this possible, for allowing me to find home anywhere in the universe. I resolved that when I got back to my real home, the home G and I made, I would tell G all about this feeling. G wouldn’t be able to understand completely, but I hoped my inner feelings would get across: that G would know how much fuller those words had made my life. And with that, G would frown and say, “You space travelers!” And I’d give the response I always gave.

“We’re all of us traveling in space.”

3

I placed the urn and G’s identity card on the counter along with my employee ID.

The employee at the reception desk glanced at the urn, scanned G’s identity card, and said, “You know this urn is too small? It won’t all fit in there. We can put in as much as will fit inside and dispose of the rest, or would you like it compressed? There’s a 20 percent compression charge.”

I couldn’t understand what he was saying.

“But it’s a standardized product.”

The employee lifted his head, looked at me, and explained, in a slightly friendlier tone, “This is a standardized urn, pilot specification. Pilot urns are made smaller than regular ones. By 60 to 70 percent. How can I put this? Space pilot urns aren’t really for storing remains at all—they’ve just been given the same name. But in this case, because this, um, this deceased person is an adult, and was actually cremated, the ashes won’t all fit inside.”

I stood there blank. I’d found the urn at home. It was one of the many things G left behind. Fitting for a groundling, G had a huge number of belongings. G said that amount was exactly the average for people in Sector 15. On the packaging for the urn, which I’d found in a box under G’s desk, it definitely said “Standardized Urn.” Did it say “Standardized Pilot Urn”? Did I fail to register the word “Pilot”? Was that even possible?

“If you come straight back with a new urn we can put everything in it for you. This is the last day of dispo—handling, so please be understanding of the fact that we cannot extend the storage period any longer.”

“How would ‘the rest’ be dealt with?”

“It’s stored in an appropriate place designated by the Corporation, then after a certain period, it is handled in a dignified manner.”

He said this with an expression and tone of voice that indicated he’d said the same words countless times before. I thought of Life as a Space Pilot’s Next of Kin: Caduceus Takes Care of You.

“Compress it, please.”

“Okay, no problem. It will take an extra fifteen minutes. There’s a waiting room on level twenty, please wait there.”

“I’ll wait here.”

“That’s against regulations. Please go to level twenty.”

The employee’s tone carried a solid authority. It was the prepared authority of the Corporation. I couldn’t wait for fifteen minutes here, in the lobby of the crematorium. Why? There was certainly a reason. There’s a sensible reason for everything the Corporation does. Perhaps if I came face to face with another bereaved person who had come to collect the remains of their loved one, they might get more agitated, and if that happened, a greater number of people would have to be stabilized, consuming more resources in the process. It was also possible that a bereaved person waiting in the lobby might ask something more of the employee, thus using up more energy than was required for their duties. Or maybe it was because every minute, every second, that I spent standing here vacantly, not working and not resting in order to fulfill my next assignment better, but waiting for G’s remains to be compacted by 60 to 70 percent, was, for the Corporation, a waste of valuable energy.

I handed the urn over to the employee obediently and went up to level twenty.

4

“You space travelers!” G said.

I burst out laughing.

“I knew you’d say that.”

“Ah, but I was wrong.”

“Why? What did you think I’d say?”

“I thought you’d say ‘We’re all of us traveling in space,’ of course.”

“Ah! Right. I was about to say that, actually.”

“But turns out it was me who said it this time.”

I fiddled with the ends of G’s bobbed hair.

“Did you get it cut yesterday?”

“This morning.”

“How long did it grow? I told you I wanted to see it.”

Our time passed by a little differently each time. While I was traveling in hyperdrive, having passed through a space jump acceleration portal, G’s time carried on at the rate it does on Earth, and so much more time passed. G’s hair would probably have grown long while I was away. Maybe not enough to reach G’s shoulders, but perhaps enough to be tied up. G always had the exact same length of haircut when I was there, a kind of short bob. Although I whined and begged to see G’s other hairstyles, G just laughed it off.

Looking at old photos, G’s hair used to be really striking. One time, G had shaved it all off, and at another time, dyed it purple. In one photo, G had a messy perm; it looked so tangled any comb would snap before getting through it. Looking at the time order, the long styles got steadily longer and longer and then every so often got short all at once. But since meeting me, G never changed the short bob from when we first met.

G’s time flowed at a constant speed, and for G there were thirty-something years of past left intact. The records of G’s life piled up smoothly, year by year, at steady intervals. I missed all those Gs of the past, all the Gs I wasn’t able to meet. I lost myself in that continuity of Gs, something that was unavailable to me. When we first combined our households into one, I got so absorbed in looking through G’s records that G ended up telling me off. G begged, “Please, just turn off the screen and look at me, I’m right here alive before your eyes.” How could everything change like this at such a constant rate and degree? How could one person’s life flow along in such a perfect stream? Is this the speed of nature?

“A life isn’t something that can be more natural or perfect. It’s all relative.”

On that day, I had asked so earnestly that G continued explaining: “I was born and raised here, and in spaceship construction they hire new workers all the time, so I ended up building spaceships. Almost everyone here ends up working for the Corporation anyway. I had no real reason to move away for work, and as I was already here, I decided to go into construction. They took me on, so I just thought it was meant to be. If I wasn’t hired by the Corporation I’d probably have ended up doing maintenance work in the neighborhood I lived in with my parents. Or else, what? I might have found a job in a local shop. But I think I probably would have just waited until the Corporation gave me a job. Anyhow, I think I would have stayed put here, and never felt the need to go anywhere else. I’ve never had to think about time or space like you do. But I’m not convinced that my way of life is somehow more natural. I mean, my life is pretty average. Most people do live like me. But, in its own way, isn’t your life natural for you too? I don’t know what to call it, the way of the pilot? From that perspective.”

“You think so?”

I remembered the shock I felt, like being hit by lightning, the first time I heard the phrase “We’re all of us traveling in space.” I was just three years old. I remembered how my preschool teacher had recommended me to the Corporation when I was five. And I remembered the day I left home, at eleven years old. How my family said goodbye as though they would never see me again. Come to think of it, I never did see them again. It just turned out like that, “naturally.” From that day on, my memory is just bits and pieces, little separated fragments from my years at Flying School, a time that seemed like it would never end, and my first flight with the people I met there. My memory didn’t flow like G’s. There were a number of lightning rods planted here and there in my life, swallowing lightning, and G was the biggest lightning bolt of all.

5

The Corporation was always looking for new laborers on spaceship construction sites because they were such dangerous places. Spaceship construction is dangerous work. It’s the work of building very large homes to very precise specifications. Even the smallest spaceship is much bigger than a person. Even the most delicate piece of equipment is a huge work of heavy machinery. And the Corporation does not exert effort preventing accidents. It’s reasonable. Preventing accidents is high-cost and low-return. It makes sense to only prevent accidents where the cost of sorting things out afterward is more than they would have to spend for prevention.

Is it reasonable?

At level twenty of the crematorium, divided up like the inside of a spaceship, I went into one of the empty rooms and sat down. I thought about what G left behind, the pilot-specification urn that was probably bought for me. When did G buy that urn? Was it a few months after we met? Or else a few years? What must G have been feeling then? It probably happened when I was away. What flight would I have been on? From which point did G decide to stay with me until I died? Looking back, I had never asked. We fell in love, brought our bodies together, and combined our homes, “naturally.” When I was with G, for those moments, my life passed slowly. It flowed as though I lived like that all the time.

I heard that the accident was very straightforward. It was a simple overhead conveyor that dropped its steel plate load one time out of every 100,000. There wasn’t always a steel plate loaded into the device when the malfunction occurred, and it wasn’t as though there was always someone below when a steel plate was dropped. The construction workers avoided the route of the overhead conveyor, too, to a certain extent. It wasn’t enough of an issue for the machine to need upgrading, nor was it enough of a problem for the Corporation to go to the trouble of cordoning off a set route for the workers that would go around the path of the device.

When I came back from my voyage, the collection of G’s remains had been completed. The storage period had been automatically extended to ten days after the submission of my landing report. In consideration of G being the registered partner of a space pilot, the storage fee was also taken care of. I was enrolled in a compulsory course of counseling sessions, and once I passed a psychiatric evaluation, I’d be assigned freight vessels on short-distance routes for a certain period. The Corporation had already arranged everything. All I had to do was give my body up to the Corporation. If I hadn’t found the urn under G’s desk after staying shut up in the house until the last day of the storage period, who knows, perhaps G’s remains would have been delivered to me in a citizen-standard urn provided by the Corporation. Or perhaps the Corporation really would have handled G in a dignified manner. Perhaps a therapist with a grief-stricken face would have knocked at the door holding the urn. Because I am a space pilot, if I were involved in an accident, dealing with it would be more costly than measures for prevention—unlike with G, who was an average worker, hired to a factory near home to make spaceships, never leaving this one planet, because it seemed like the natural thing to do.

6

Becoming a space pilot was a process of preparing to die. Only exceptional people, who were ready for every possible situation and prepared with the right way of dealing with any scenario, were given the opportunity to die in space as pilots. I learned the ways of the space traveler. I learned to accept the decisions of the Corporation and never ask questions. But they never prepared the person ready to die to cope with the death of their loved one. This was always a possibility, but I guess it wasn’t something worth preparing me for in advance. A thing that could happen, and if it did, a thing that could be dealt with by giving orders for counseling sessions. Just one possible eventuality, something that could have happened at any time.

7

I’ll probably end up living a really long time. Adrift between one home and another.