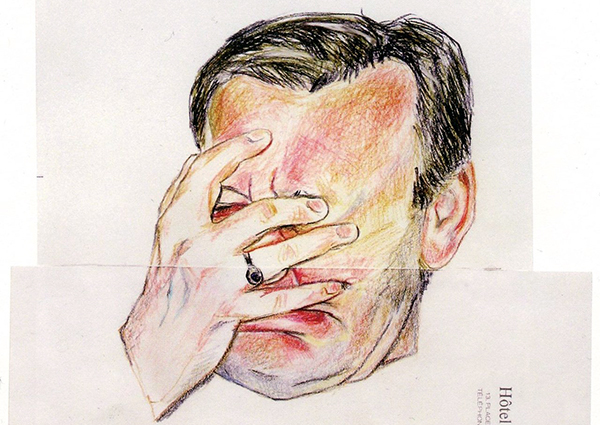

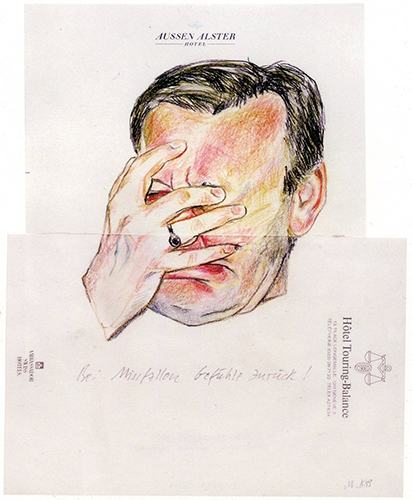

© Martin Kippenberger.

Philip Finch, known to everyone but his aged mother as Moose, was driving to the hotel in his fail-safe Škoda 120, a car the color of old chocolate gone chalky. His window was wound down so he could tap ash onto the street and blow smoke out of the side of his mouth. It was important that his daughter shouldn’t have to inhale his mistakes. She was in the passenger seat wearing her classic early-morning look: black skirt, white blouse, an elegantly expressionless corpse. Her hair had been cut yesterday. He saw no discernible difference. He told her it looked very good.

“Nothing good has ever been produced by a Wayne, Dad.”

They passed the Dyke Road Park and the Booth Museum. Freya started rummaging in the glove compartment, a minor landslide of cassettes. There was a system and she was spoiling it. “What are you looking for?”

“Music.”

“We’re five minutes away, Frey.”

She yawned. Blinked. Considered the windscreen. “It’s hot,” she said.

“There’s some Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders in there. That one I played, where were we?”

She sighed.

“You’re sighing.”

“Nothing good has ever been produced by a Wayne, Dad.”

“Untrue,” he said and fell into a long dark reverie from which he emerged with the name Wayne Sleep.

“Who?”

“Or…” Where were all the other famous Waynes? “John Wayne.”

“Surname,” she said.

“That makes him a deeper form of Wayne. His Wayneness is in the blood.”

“Probably a stage name,” she said. Which, now that he thought of it…

He changed down another gear—these conversations were precious—and told her she shouldn’t write things off until she’d tried them.

“Like traveling, you mean.”

“Like university,” he said. “Traveling, Frey. There’s nothing special about traveling. This right here is traveling—going to put those back, at all? You can find yourself and lose yourself in this very car, this town.”

“Thrill a minute,” she said, but he thought he saw the flicker of a smile.

She was eighteen years and a dozen days old. Just yesterday, it seemed to him, she’d emerged out of an awkward bespectacled adolescence—a phase in which she’d temporarily lost the ability to be appreciative, the ability to be considerate, and the ability to be apologetic, all while causing a great proliferation of opportunities for these states to be warmly deployed. He’d noticed, of late, a big upsurge in the number of masculine glances clinging to her clothes and also in the ways she didn’t need him. Seldom asked his advice anymore. Knew how to deal with difficult customers. Would one way or another soon be leaving him behind. Her mood swings had settled into a dry indifference, a much narrower emotional range. At times he felt nostalgia for her earlier anger and found himself needlessly provoking her. University! Careers! When might you learn to lock the door?

There was an awful pregnant pathos to this: your perfect daughter becoming your then-perfect wife, slinking into a future where she’d fall prey to certain enterprising, highly sexed individuals who were suped-up versions of the once-young you.

With her pale skin and dark eyes and button nose, that fatal way of raising the left eyebrow in arguments, Freya was increasingly a Xerox copy of Viv, back when they’d first got together. There was an awful pregnant pathos to this: your perfect daughter becoming your then-perfect wife, slinking into a future where she’d fall prey to certain enterprising, highly sexed individuals who were suped-up versions of the once-young you. He sometimes overheard summer staff at the Grand talking in an advanced language of sexual adventure, discussing what he assumed to be new positions or techniques. The Cambodian Trombone. The Risky Painter. South-East England Double Snow-Cone. Did anyone still do missionary? The future bares its breasts and laughs, a gaudy county fair.

Truth was, Moose hadn’t had sex in a while. The one great difficulty of his job was the fact of being surrounded, at all times, by people engaged in sexual communion. Guests were having sex against walls and on hushed carpets, in storage cupboards and on sea-view balconies, in gooseneck freestanding baths and walk-in showers and probably just occasionally on beds. Forty-five. Too young, definitely, to have taken retirement from romance. But it was more of a redundancy-type situation, wasn’t it? A severance. Lust running on without opportunity, not unlike a headless chicken. People still occasionally made remarks about his appearance—remarks interpretable as compliments—but he was often too busy to follow up on such leads. He’d had only a handful of flings with women in the years since Viv had left him for a guy called Bob; Freya at that time was thirteen. Possibly he’d have to relax his no-guest rule. There was always someone lonelier than you were. He struggled sometimes to shake the idea that his early life had been all about an excess of sex and a sense of bottled potential and that these things had, in the rich tradition of life’s droll jokes, been replaced by an absence of sex and a sense of wasted potential.

“New skirt,” he said.

“No.”

“New haircut, though.”

“We’ve covered this,” she said.

He flicked the indicator. Reminded himself to waterproof the passenger window. Masking tape before autumn really kicked in. They passed a Labrador walking a lightweight woman.

Frey mumbled something.

“You’ve become a mumbler,” he said.

“Wendy told me to tell you hello.”

“Did she? That’s nice. How was she then? Still dying?”

“Yeah. Bit more each time.”

“Good hair though.”

“Hmm.”

“I bumped into her in Woolworth’s a few weeks back. Forgot to say. Complained to me about an ingrowing toenail. I thought it might mark a new move into realism.”

“No,” Freya said. “There was no mention of toes. She was back to brain tumors and surgeries.”

“Shame.”

They rolled on through Brighton’s breezy, straight, and safe-looking streets, lamp posts spaced out and rooflines designed to rhyme. Girls in white denim walking, ponytails flicking. Women in smart dark jackets, narrow at the waist and wide at the shoulders. Crazy baggy T-shirts giving gangly kids space to hide. The summer not yet over. That special summer hum. The Prime Minister was coming to stay in a few weeks’ time. He knew her visit was a route to promotion. To future GM opportunities in Oxford or Bristol or Durham, wherever Freya ended up studying. Money, too. His current £14,000 a year didn’t go that far. He needed to provide and provide. He’d earn more as a doorman or a bellman—those guys built houses out of one-pound coins—but if you were a doorman or a bellman you were a doorman or a bellman for life, addicted to tips and shorn of the chance to advance; he’d seen it happen many times. A salaried position had a future. That was the idea, anyway.

The British approach to sunburn was simple: get out there and upgrade yesterday’s patchy burns into something of more uniform severity. The recklessness of his own heat-seeking people made Moose oddly proud.

Left onto the King’s Road, a modest milk float trundling past them. On his right, the vast glittering sweep of the sea. Late-season holidaymakers, towels slung over their shoulders, crossed the street to reach a warm swerve of shore. Gray stones and beige stones, some slick and some dry. The British approach to sunburn was simple: get out there and upgrade yesterday’s patchy burns into something of more uniform severity. The recklessness of his own heat-seeking people made Moose oddly proud. Paint was peeling from the candyfloss huts, faded seaside glamour.

The Grand came into view, one of the loves of his life, a giant white wedding cake of a building facing out onto the English Channel. The wide eaves, the cornices, the elaborate brick enrichments. The Union Jack slapping high. He loved the twiddly little features and their special arcane names. One hundred and twenty years of stinging drizzle, of corrosive sunshine, of the salty gales and acidic bird shit that is every coastal town’s cross to bear.

What he loved most was walking into the Grand with his daughter at his side. Yes, I created this person, look. A tiny moment of ego in an industry that was all about accommodating others. His favorite doorman, George, waved as they got out of the car. George who always had an umbrella in his hand, forever expecting rain, and touched every bit of luggage the moment a car boot opened, for once your hand was on the handle a tip was almost certainly yours. Then Dave the Concierge with his wide friendly face and breath that always smelt of aniseed, a strategy to conceal his fondness for Scotch. He bowed for Freya in mock-theatrical style, a move that made her laugh each time. Derek the Bellman simply nodded. It was said that he had a picture of Bernard Sadow on his dartboard at home, the guy who’d invented the suitcase with wheels.

Within these Victorian walls, Moose’s style was excessive. The Grand was all about excess. He was living through excessive times. He didn’t have the money or inclination to wear expensive suits, to buy designer gel to sophisticate his salt-and-pepper hair, and although he had a head for maths he lacked the inner shard of ice that was probably required to make it rich in merchant banking. So instead he wore his navy-blue Burton suit—a suit for a man who was neither tall nor short, neither fat nor slim—and created little performances out of thin air, words and gestures that made his guests feel special, his name badge pinned close in on the lapel, his tie hanging over the nearest portion of his title, concealing the word DEPUTY, leaving only GENERAL MANAGER, a promotion without the salary or associated sense of pride. His stage was the lobby’s Persian rug. He liked the thick cream scrollwork of the ceiling, the gleams in the bends of the luggage trolley, the decorative panels that made him think of Malted Milk biscuits, the soft wattage of elegant lamps. He liked the Merlot-colored curtains keeping the parlor rooms calm. The heart of house was dingy corridors and piles of dirty laundry, but the front of house, the areas guests saw once they had passed through the glittering wings of the revolving door, was full of the warmth of opulence, the mellowing air of antiquity, the fragrance of fresh flowers. First thing you felt coming in—the door’s revolutions slowing—was the hush of wise furniture inside. Duet stools and wing-arm chairs. The Gainsborough nestled under the first dramatic arc of staircase. It was upholstered in Colefax & Fowler Oban Plaid.

“Mr. Barley, how’s that nephew the newscaster doing? Lovely profile in the Argus.”

“How was that champagne, Mrs. Harding? Did it live up to the no-hangover guarantee?”

“I’ll get that console table replaced, Mrs. Mathis. A woman of your stature should not have to stoop.”

“A seaview suite?”

“Some aspirin?”

“A doctor?”

“A florist?”

People were very regular in what they overlooked, and also in what they left behind: pajamas, handcuffs, once a prosthetic leg.

Smell of fresh coffee in the morning. Tea and cakes come afternoon. Toothbrush sets behind the desk. Hundreds upon hundreds of condoms. Knot cuff-links by the dozen. People were very regular in what they overlooked, and also in what they left behind: pajamas, handcuffs, once a prosthetic leg. Moose was a secular man. He would have liked to remove the Bibles from the rooms, or else to add copies of the Koran, but they were hugely popular among the summer staff—the thin pages were apparently handy for rolling joints—and if a thing made you feel better, and you practiced it discreetly, who really had a right to object?

On days when ambition and regret got the better of him, when lost opportunities stuck to his shoes like bubblegum gone to ground and created ugly slouching strings that halted progress, he told himself that all human life was here. Yes, the affairs. The stuff everyone always asks you about. Definitely those things. But people also got engaged and married here. They received phone calls telling them their parents had died. They conceived children. They blew out candles.

He was happiest of all when talking to guests. If it wasn’t for the editorial influence of deadlines and to-do lists, he could easily pass whole days discussing their get-richer ideas and much-mourned ailments, the Platonic ideal of a pillow, its consummate softness and girth. He liked to know every guest’s name and to slowly fill out the lives underneath. When regulars were the kind of people who enjoyed saying hello he tended also to know the names of their children. When they went about their days closely guarding their privacy he nodded and smiled, held a mirror up to their reticence. Hospitality involved an aspect of surface flattery but also of deep familiarity. It was a peculiar combination of density and gauze. You were reading people all the time, reading and reading and reading, and only occasionally was his apparent fondness for people false. The odd smile delivered to a slick pinstriped guy who was really no more than a slippery fish in the sea of his own possessions. The occasional compliment to a woman whose post-operative breasts were even more determinedly inauthentic than her eyes—eyes that were blank screens upon which brief impressions of felt experience flickered. In the main, people were kind if you were kind. They wanted to have a good time. You gave them the best and worst of yourself. The huge lie that you would escalate their complaint to Head Office. Telling the truth, almost always, when you wished them a very good stay.

Mrs. Harrington from room 122 was doggedly crossing the lobby, swinging the walking stick she rarely seemed to need. Old Mrs. H was one of the Grand’s most reliable regulars, and she only ever stayed in room numbers that added up to five. Many front-desk staff had learned her proclivities the hard way. “Room 240 is lovely, Mrs. Harrington.” “I’d prefer not to, dear.” “Room 301, perhaps?” “I’d prefer not to.”

“Punctual as always, Mrs. Harrington.”

“You,” she said with a hospitable grimace. “Still poorly?”

“Poorly?”

“Pale.”

“Me?”

“Roller-coaster,” she said, and traced a wavy line in the air with the ferrule of her stick.

Moose tried to laugh but managed only the maintenance of his current smile.

“Arm pain,” she said.

He felt his smile fail him. “How did you know?”

“You confided.”

“Did I?”

For a moment her eyes slid sideways towards another regular, Miss Mullan. On every other week of the year she was Mr. Mullan, chairman of a FTSE 100 toiletries company.

“Perfectly fine now, thanks, Mrs. H. A little sprain. I’m not dead yet.”

“Geoffrey said that. My Geoffrey, before he died.”

“I’m sorry,” Moose said. “That was thoughtless of me.”

“His death,” she said. “Second-best thing that ever happened to me.”

Mrs. H couldn’t move her shoulders much, so to indicate a shrug she simply turned the palm of her right hand towards the ceiling. “His death,” she said. “Second-best thing that ever happened to me.”

“What was the first thing?”

“Motorcycle,” she said, and continued her voyage towards the restaurant.

The breakfast crowd parted as she waved her stick on a low axis from side to side, as if it were white and she were blind, the wood knocking at shins and kneecaps, opening a path to where the best table was.

With Freya safely installed behind the reception desk, her chin on the heels of her hands, still frustratingly bad at disguising her boredom, he did his usual check of the restaurant (tidy) and the lavatories (shiny). He walked up to the first-floor storage room, where the hotel held long-term luggage and other items like cribs and wheelchairs. There had been a spontaneous staff party in the hotel last night and sure enough he now located, in a dusty corner, a few dozen miniature bottles of booze. A condom wrapper too. Jesus. An untouched Marathon bar. Interesting. He ate the Marathon and found Mimi from Housekeeping. Asked her to put the unused items back in the minibar cupboard and ensure that it was double-locked. No 1-1-1-1 combinations on padlocks, please. Then, coming down the thickly carpeted staircase, careful not to touch the handrail and impart unnecessary smudges, he passed Chef Harry’s temperamental tabby cat, Barbara. Usually she begged for food. Lately she’d been depressed. Gave him a withering droopy-whiskered look that seemed to say “What’s the point?”

“This is as good as it gets, Barb.”

She pinned her ears back and yawned.

He asked Marina, the Grand’s Guest Relations Manager, whether there’d been any further press inquiries about the conference, or any changes to the block-booking numbers supplied by the Prime Minister’s secretary’s secretary. There hadn’t been, so after he’d marveled at the wondrous way she blew upward at her hair between sentences, the soft fringe fluttering darkly, he took his disappointment and arousal to the cupboard he called his office. A memo to finish. A briefing pack on important guests. Documents authorizing the installation of extra security and CCTV—nine cameras, twelve, the requirements kept shifting. Paper sprouting from his IBM Wheelwriter. No natural light in here. Assuming the overall manager stepped down in a few months, as planned, and assuming also that the PM’s visit was a major success; assuming all this and assuming that the Group Executive Committee was as good as its word, Moose would soon be moving upstairs into an office with a door plaque saying “General Manager.” Overall control. Decent salary. Sun and sea view. He wished he were not so reliant on recognition, but it gave him the little lift he needed to get through each seventy-hour week.

Paragraphs taking shape. Letters sometimes interlocking. Clack clack clack and only four errors. The dyslexia always an itchy label on his thoughts, irritating his attempts at eloquence. The calendar on the wall showing sun touching fields and September festooned with breezy leaves. He was in the habit of crossing out each finished day, boxes of canceled life, a pencil not a pen, as if he might at some point want to reinstate a long-lost Tuesday. The filing cabinet had his little gold statuettes on top, men with torsos that were upside-down triangles. They were standing on the edges of diving boards. Along with the hatstand, these were his favorite office item.

The thing about hats was, you never knew when you might want to start getting into them.

Did he own any hats? No, technically he did not. But built into his belief system these days were a number of convictions—never take taxis, never be afraid of combining carbohydrates—and one of them was that a hatstand was something every man ought to have. The thing about hats was, you never knew when you might want to start getting into them. Freya had said to him, “Why don’t you use it for coats, in the meantime?” But his daughter was missing the point. He was saving the hatstand for a hat. He could picture it: the first delicious instant when, with casual carefulness, he’d toss onto one of its lovely curling limbs an Ascot cap, a Balmoral bonnet, a beret, a boater, a fez or a fedora. It was a small moment of magic he’d stored up for the future.

He reached for a folder entitled “Conservative Party Visit” and began to refine his strategies, taking breaks only to phone universities and ask them to send more prospectuses.

In the afternoon there was a meeting with the following agenda:

1. Alarm clock roll out. 201 + spares. Testing committee. Features. LED light? Serving the long-sighted, late-sleepers, etc. (PF)

2. Napkins for functions during conference. Scottish supplier. Problem? Conference blue? (PF)

3. Snagging request from Cameron House. (PF)

4. Training prog for additional temporary staff. (PF)

5. Canapé vote. (PF)

6. Fax machine installation. (PF)

7. Mitigating annoyance of CCTV for non-conference guests? (MV)

8. Towels not soft enough—what’s the point of trying to be cheap on fabric softener? (DN)

9. Riots. (PF)

10. Irish protesters. (PF)

11. Security threats. (PF)

12. Any other business.

In the “any other business” section of the meeting—so seldom used for anything except birthday announcements—there was a discussion about the fact that the hotel hadn’t suffered an overflowing bath for the best part of nine months, which was thought to be a record. There was also a complaint from a maid about further strings of semen found on floral-pattern curtains. Who were these curtain fuckers? What was their plan?

Once item 12 was dealt with, the ever-sleazy Peter Samuels asked Fran a mischievous question. She was the p.m. Housekeeping Manager, a black lady with striking eyes. Turndown, purchasing, scheduling. Thirty-two staff under her command.

Fran said to Peter, “Nah, no no, not what happened. Here’s the story. OK. So. The wife came out of the bathroom, yeah? Wet and naked.” Fran paused for effect. Silence fell around her. Only Marina smiled. Perhaps she’d heard the story already. “And this guest, she’s wearing nothing except a skimpy little white towel tied up around her hair. This is when I’m covering for one of those lazy-ass summer girls, Veronica the Vomiter, you got it.” A nervous laugh from the assembled staff, two of whom had personally recommended Veronica for the job. “And she says to me, this guest, her tits out, her ass out—everything out—she smiles and says all casual, ‘Carry on, darling, but shut the curtains, will you? I don’t want the neighbors seeing me naked.’”

Hush around the table. Men full of longing leaned in. “What did you do, Fran?”

“Well,” Fran said, “I carried on making the bed, didn’t I? And then I explained to her, real polite, that if the neighbors saw her naked they’d shut their own fucking curtains.”

The room exploded. Fran had worked in hospitality for the best part of three decades. Her principal complaint about the Grand was that tights weren’t supplied with the uniform.

As the sky over the Channel became a deep purple, only a few fragile coral swirls surviving up high, Moose took a seat in the bar area for his pre-dinner beer and cigarette combo. His Zippo was engraved with the words “To Viv, Love Phil.” His ex-wife hadn’t shown much commitment with her smoking. Marina came over, clutching a pack of menthols. Moose provided a flame. The best thing about smoking was that people like Marina sometimes asked you for a light.

He dropped a twenty-pence piece into the till, opened a packet of crisps, pulled up a chair for her. Pictures of famous guests adorned one wall: Napoleon the Third, John F. Kennedy, Harold Wilson.

“Take a holiday, Moose,” Marina said. “A couple of days you could spare, no?” She lifted her arms. A little pink yawn as she stretched. He noted once again the miraculous mundanity of her elbows, tiny angry creatures that seemed too awkward to belong to her body.

Technically he was, via a dotted line, Marina’s boss. But the clash of continents in her voice gave the Grand’s Guest Relations Manager a worldliness he couldn’t ignore. Also: he was still suffering a little from The Infatuation. He took to heart everything she said and respected also the fact she didn’t explain too much about her past. Viv used to say there were two types of person in life, past tense and present tense. Viv had seen herself as a present-tense person, which gave her an excuse never to discuss what she felt about a thing that had already happened. She’d dwell on that thing silently instead. Marina, though, was genuinely present tense. She inhabited it. Owned it. Male staff members at the Grand waded through the myths that surrounded her, enjoying the feeling of being stuck. The story that she’d once been married to an adulterous game-show host in Argentina. That she’d previously been a model and a children’s entertainer. That recently, on her thirty-eighth birthday, a woman with short blonde hair had proposed to her in a cafe in the Lanes. No one quite knew what was true.

“Want one?” he said.

Marina shook her head.

The first three crisps he ate individually, seeing how long he could keep them on his tongue before succumbing to the crunch. The rest he crammed in quickly.