I feel like I don’t even exist. The words floated on the white gallery walls, vanishing quickly. Another sentence followed: Today, I realized I’m not crazy.

It was a loop of pain and rage, without audio; the gut-wrenching words of two hundred women who have been the victims of domestic violence, half in Colombia and half and in New York City, engaged in a ritual to transform their suffering.

For years, Cartagena-born and based artist Ruby Rumié thought about their plight, reading emotional stories in newspapers local to the areas where victims were most often victimized. What happens, she asked herself, when you are frightened or angry? The answer came immediately: You lose your breath.

This was the inspiration for a conceptual art project, Divine Breath, at the Nohra Haime Gallery in Cartagena, and Divine Breath NYC (Divina Halito), a new iteration that was on view at La Mama Galleria on Great Jones Street this October. As an activist artist whose work often focuses on social issues such as gentrification, class, and domestic violence, Rumié’s goal was to create a ritual that would empower these survivors and help them release their pain.

“The ritual was definitely not intended as an art performance that would be seen in public,” Rumié explained. “Rather, it was to be a private, intimate ceremony to be lived and to be experienced.” To make the women feel comfortable, Rumié received them with a social worker or a psychologist. Then, one by one, the women were escorted into a dark part of her studio where they selected a ceramic vessel that was “the size of their pain.” They sat in silence and, when they were ready, inhaled, filling their lungs with air. Then, remembering the most terrible moment of their abuse, they exhaled all of their pain into the vessel, which was immediately sealed and lacquered. The exhibit consisted of the vessels themselves, and photographs of the women holding them.

After Grace Morgan, a New York attorney and the founder of the small non-profit STREETsmARTs, saw Divine Breath in Cartagena, she reached out to her friend Wanda Lucibello, a lawyer who had spent years in the Brooklyn District Attorney’s Office overseeing the Domestic Violence Bureau and had just joined the staff of Safe Horizon, the largest victim assistance organization in the US. Morgan’s message was simple: “There’s an exhibit here that you should see.”

What resulted was a partnership between Rumié and Safe Horizon, which helped the artist find women in shelters who wished to participate in a ceremony. The women, and the names and addresses of the shelters where they were staying, would remain anonymous; they simply wrote their initials on tags, which were tied to the top of the vessels with kitchen twine. There would be no photographs of faces; only of women from the neck down, dressed in street clothing, holding their vessel out in front of them, as in the Colombia show.

Safe Horizon piloted the ceremony with their staff. so that they would be able to relay the experience to shelter clients. “It was not an easy thing to explain,” Lucibello said, “this ceremony and photography.”

Kelly Coyne, Vice President of the Safe Horizon Domestic Violence Program, said that she was a “giant skeptic” when she first heard of Rumié’s project. But she participated in the trial ceremony and confessed to the crowd at the La Mama Galleria opening that she was very moved: “I didn’t even know that I was holding back,” she said.

When Rumié arrived and visited the shelters, she was reminded of two things: First, that they were places where women were protected from their abusers, and, second, that they were places that protected women from themselves. “It’s so easy for women to go back to their old life. It takes strength to make a new life,” she said.

Bringing a version of the exhibit to New York City was a grassroots effort by Morgan and a group of friends, dubbed the Divine Breath Committee, but they found replicating the Cartagena exhibition in New York City to be a challenge. While Rumié and an assistant made the ceramic vessels used in Colombia, she knew that it would be impossible to transport vessels to the New York show. They were far too fragile to ship, but even more challenging, they would be considered suspect by US authorities. “They believe that everything that arrives from Colombia has drugs in it,” Rumié said.

So, Rumié and Morgan made an open call to ceramic artists in New York City. They began visiting studios to discuss the project and see whether the artists’ work was suited to the ceremony. Seven artists were then selected to make off-white prototypes: Rana Amirtahmasebi, Will Coggin, Paula Greif, Eleni Kontos, Ben Peterson, Biata Roytburd, and Mia Schachter. Their prototypes are installed on a shelf in the entry to the La Mama Galleria. Significantly, two of the seven ceramicists are men, an important decision to Rumié. “Men are symbolically helping women to heal,” she said.

Ceramicist Biata Roytburd felt a powerful attraction to Rumié’s project. “As a sculptor,” she said, “all of my work in some way deals with women’s issues.” Rumié gave the artists complete freedom in designing their pieces. The only specifications were the size of the piece (up to 27 centimeters tall and 16 centimeters wide), space within the vessel for breath, and a small opening so that the vessel could be easily sealed. To create her prototype, Roytburd threw three bulb-like shapes, which she connected to each other to form a tripod at the base. The big-bellied piece was attached with a slight lean on top.

Beyond the prototypes, on a long plinth, were the 100 off-white New York City vessels, on either side of which Rumié arrayed the photographic murals of the 100 white Colombian vessels and their New York City counterparts.

Rumié spent the entire month of July in the city, accompanied by a member of the Divine Breath Committee, traveling from shelter to shelter with her suitcase and camera equipment in tow. “It was as if I was selling encyclopedias,” she said.

Often she brought along food for after the ceremony. Some of the women were silent. Others began to cry. “It came out of them like waterfalls,” Rumié said. “When we recognize this profound pain and we let it go, we begin to construct a new life. That’s why I called it Divine Breath, because it is the first pure breath that comes out of a wound, out of a hurt soul.”

One day, the babysitter Safe Horizon hired to watch the children while their mothers participated in the ceremony did not show up. There was a little girl, about four or five years old, who sat by her mother, silent and observant. When her mother left for the ceremony, the girl approached Grace Morgan and asked what was going on. After Morgan explained, the child said, “Oh, I also have this terrible pain.”

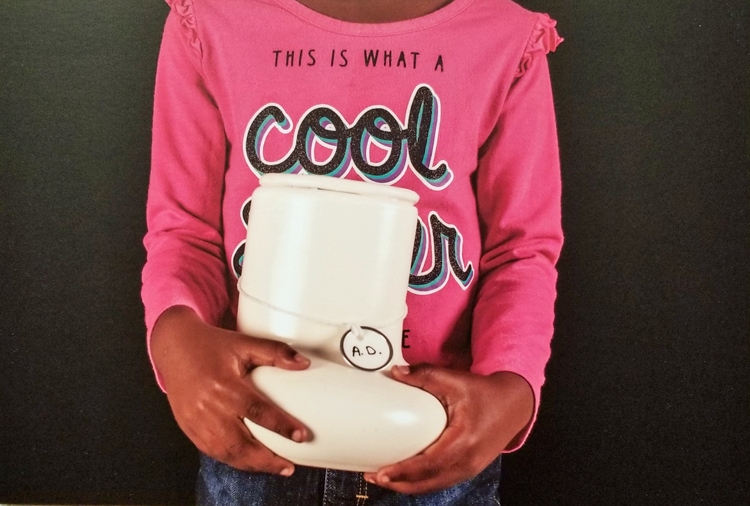

The child asked to participate, and chose a vessel of her own. “Remember a moment that really scared you, a moment that you never want to happen again,” Rumié told her. “She made the ceremony in silence,” she explained. “Everybody present was absolutely moved by this moment.” A portrait of her with the sealed vessel is one of the 100 hanging on the gallery wall, showing the torso of a young girl in a dark pink top whose message is cut off by her bulbous vessel, designed by Eleni Kontos and tagged with the initials “A.D.”

After another ceremony, Rumié embraced a woman with a three-month-old baby who had been born in the shelter. The woman was crying profusely, and cried even more when Rumié hugged her. Following her abuse, she had not let anyone touch her, but Rumié’s embrace, she said later, “felt true and honest.”

Honesty and truth: these two words describe the essence of Rumié’s activism, her art. Also on view in New York, at the Nohra Haime Gallery, is Common Place, a traveling, joint project by Rumié and French-American photographer Justine Graham, who lives in Santiago, Chile. In Common Place, Rumié and Graham explore issues of gender, power, class, and race through the relationships between Latin American housekeepers and their employers, photographing them in pairs, side-by-side.

Both artists drew upon their personal experiences. Graham grew up in France in a household served by a cleaning woman but no live-in help. Rumié grew up in Cartagena in a family with nannies. Despite the difference in their home lives, the two shared a point-of-view. “We tried to promote equality rather than do a work that emphasized difference and inequality,” Graham said. To do this, they photographed women in four cities—Bogota, Cartagena, Buenos Aires, and Santiago—all in identical white tee shirts, against the same background.

Especially important was the act of taking these women to a neutral space to be photographed, removing them from the domestic space and the power relationship it encapsulated. “White t-shirts disorganize the social constructs,” Rumié said. Equally disorganizing is photographing the women without makeup. “Throughout Latin America, upper-class women do not use much makeup, while middle-class women do. This is their way of saying that they are not middle class,” Rumié said. “We shook it all up. No fancy clothing. No makeup. We photographed them from the front and the back, because the body tells stories.” Often, during their photoshoots, the nanny began to shrink unconsciously beside her employer. “We kept telling her: You are curved. You have to be straight.”

The women answered a questionnaire that began with their age, nationality, and weight, then moved on to more personal questions: At what age did you lose your virginity? Have you had an abortion or a miscarriage? What book is on your night table? (Most answered The Bible.) What is art to you?

Graham and Rumié also shot a video of the employers and their housekeepers dining together. “Ninety-five percent of these women, despite their good relationships with their employers, do not sit down and eat with their nannies,” Rumié said.

At the opening, gallery goers were given a sheet with 80 pairs of photographs and were asked to check off the face of the employer. The person who guessed all of them correctly would win a print. “Look at their backs,” said one young man, a filmmaker, giving me a tip. “You can tell who is employed by their hair.”

The competition is open until November 16th. So far, of the 200-odd images, only one person has identified all the employers.