My father’s bedroom also turned out to be his mausoleum. He was buried under his bed, the grave flattened back into the cracked grey cement floor. Our tradition demands that elders must be buried inside their personal rooms. I can’t remember now who did it, but while the cement was still wet a short epitaph was engraved on his grave: B.A. Ehikhamenor 1924–2004.

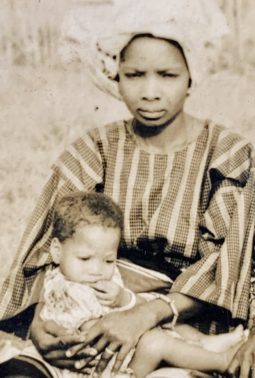

Eleven years later, my mother was buried in her ancestral village, not too far from my father’s village. Her younger brother, Uncle Ephraim, had loved her deeply and wanted her buried inside his living room, but that was not the tradition. We buried her by the side of the house in which she was born, eighty-nine years earlier. I have not visited my ancestral home since her final burial rites. Most houses in my village—once filled with men, wives, children, and festival celebrations—have emptied, their memories overtaken by weeds.

As these places fade to my periphery, what was peripheral there takes on central importance in my imagination: Photographs. Old suits with swollen pockets filled with money tied in hankies. Reused gin and beer bottles filled with herbal concoctions, and water for morning ablutions. An old rusty gaslight. Political party affiliation cards dating back to 1959. The registration number of a bicycle bought on March 23, 1952. Hospital prescription notes; a gramophone with a pile of 45s; a ceramic red plate from which kola nuts were served to important visitors; invitation cards to burial rites; and, most importantly, old notebooks and letters from far and near.

My village has been hit hard since Nigeria’s urban migration began with the oil boom of the early ’70s, right after a debilitating civil war. This problem of farmers and traders leaving the village to seek the evasive glamour of the city has not abated, and my once-vibrant village is emaciated, its streets stripped bare. As of today, nobody lives in the big blue-red house my grandfather built in the ’50s, where I spent a large part of my childhood, nor the one my father built in the ’80s, where adolescence met me. Buildings, like humans, need breath, which is how the strongest blocks and stones survive time without crumbling. This debacle prompted me, in December 2019, to implore one of my uncles to help clear out my father’s room, rescuing his old furniture and the voluminous documents left behind from his meticulous record-keeping.

I’d ignored the two hefty Ghana-Must-Go bags sitting in my house since they’d arrived, like loved but unwelcome relatives. Why? Maybe for fear of what might be inside, or because I don’t handle nostalgia too well. The past overwhelms me as a visual artist and writer; beautiful memories often make me cry. But not knowing exactly when COVID-slowed life will return us humans to the rat race, I continue on reliving my father’s life, introducing him to my children, who never met him, and laughing at his ebullience with my siblings through phone calls and text messages. It felt right. These days call for self-reflection, relationships, family, and a renewed meaning of life.

With the care of a lepidopterist and the precision of an archaeologist, I set upon my father’s mementoes: fossils of unrecognizable insects, dead-and-dried rats, remnants of roach-perforated papers, school report cards made frail by dampness. Dust rises from each bag. Inside, family history dating back to the 1930s, in all its rusty brittleness.

Rats, roaches, and rains had become the biggest threat to the images and letters left behind by my father. Time has also begun to eat away at facts I carry in my mind, the way insects and rodents attack these mementoes. An astute local historian, my father maintained a pristine record of his entire life, and that of other villagers, in notebooks and on loose papers, packs of cigarettes, backs of torn calendars, or any other material he could lay his hands on. Though he never saw a four-walled classroom, B.A. Ehikhamenor was meticulous in handling and recording information.

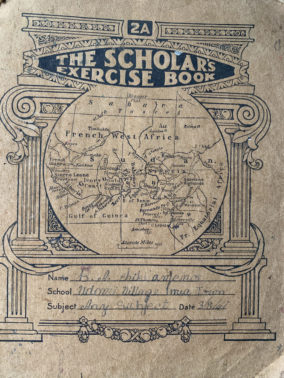

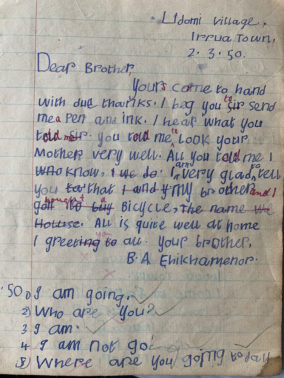

The oldest notebook in this archive has, on the inner cover page, my father’s very first written words in English: “My. Name. Benjamin. 1945” and the first page is dated “Oct 25th 1945,” followed by “Dear brother, I want you to send me a reading book.” As he progressed in his homeschooling, my father wrote a letter of request to my grandfather asking for a wife. I laughed at this. One’s heart-desire will always appear. Though the letter was a classroom exercise, it showed what was on the young man’s mind then: that was 1947, the year he married my mother. And on July 30, 1953, he recorded the purchase of his first Raleigh bicycle, registration number BN50778. In the ’50s, a bicycle in my village was equivalent to today’s Rolls-Royce in the city. These notebooks also have aphorisms such as, “A lazy boy shall be a poor man,” “No food for lazy man,” “The young shall grow.”

Armed with a minimal education, my father took upon himself the task of recording the mundane happenings of daily life, from births and deaths in the village to bizarre occurrences, like the year a brush fire set by an unknown arsonist almost consumed the village, including my grandfather’s plantations. His record-keeping diligence was well-known and trusted. It was not uncommon for two people arguing about their birthdays, marriage dates, or the year locusts wiped out every farmer’s crops to come to my father for clarification. Sometimes he did not even have to consult his notebooks; he would close his eyes briefly like a wine-taster, stare into empty space for a few seconds, and start reeling out information as if he had just searched a database. He’d relay the exact dates of each person’s birth and the circumstances surrounding it. Which was how I knew how our village’s postmaster, the son of a moonshine seller, at whose fenced compound we had many disco parties as teenagers, had within his name, “Hitler.” My village’s Hitler was born in 1944. News of the original one, then the world’s biggest villain, had filtered into the ears of villagers like an airborne disease, without them knowing how hideous Adolf Hitler was. A few parents named their male children after this inglorious white supremacist, pronouncing it “Itila.”

My father also kept clean records of his debtors, as well as of those who trusted him to be their personal banker. These financial records chart history in currencies, beginning with the pound and shilling of colonial rule and shifting later to the naira and kobo. My oldest sister went to school on pounds and shillings, while the rest of us were trained with naira and kobo. Receipts of every school fee payment, every taxation, every request from distant relatives for a short-term loan, were neatly kept in various beige/brown/white envelopes, and in empty packs of sweets and cigarettes.

When I was at home, I’d seen him laboriously spell certain words that had escaped his memory as he aged, with handwriting in the shape of tiny nooses and dry twigs stacked together. As my father grew older, his scribbles started looking more visual than textual, similar to my chalk and crayon drawings as a kindergartener. Some of the writings I am reacquainting myself with now wouldn’t make sense to a stranger, but I know because I am familiar with what he was trying to document—the names and dates will be correct, but the spelling has to be guessed at. For instance, “born” is spelt “boon” in many instances. His clean cursive handwriting in the late 1940s, when he first discovered the beauty of the written word, was now sliding, because it was hard for a hand that handled farming tools every day to be nimble with the nib of a pen over time. My father never relented in his record-keeping ritual, as if he were scared of losing the little education he had. All his writings, notebooks, unused envelopes and blue writing pads, stamps and early letters from the city were kept in two old purple/brown raffia bags that sagged from two nails above his wooden writing table. I grew up to meet these bags of memories, now with me in Lagos, where I am harvesting his mementos and family members’ secrets.

Even though my uncles and aunties lived outward successes in cities flung across Nigeria, their inner feelings, fears, and failures were conveyed in the letters they wrote to my father. I am reading all the letters again now. My childhood misconceptions make me cringe. I believed then that everyone who lived in the city was rich, royal, and well educated. My uncles carried back home to our village the powdery smell of crushed moths and talcum powder, and my aunties wore the perpetual aroma of perfume-factory workers. I hugged and embraced them as soon as they alighted from personal cars or public taxis, and their foreign smells threw us village folk off the true scent of hard city life. My city relatives put their best faces forward whenever they visited home, but the letters to my father bore private truths that differed from what I witnessed.

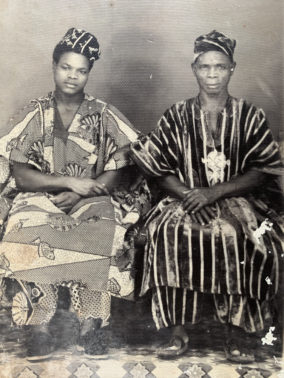

Thanks to the land my grandfather acquired in the midwestern part of Nigeria, he was a wealthy man. Together with my father, he ran an expansive cash-crop plantation, with day laborers who tapped rubber and harvested cocoa, oranges, and tangerines, then packed them into lorries off to city markets. In those days, a man’s wealth was measured by the number of his wives, and my grandfather had six. Two of them gave birth on the same day, making my father and my Aunty Comfort some kind of twins. All of those wives, with all of their children, built my grandfather a labor force fit for agrobusiness, and he used it.

But my grandfather Ehikhamenor, also known as Agbadamu, or “the one who packs money in his robes’ pockets,” sensed the shift in world order quicker than most other villagers. He had long had some idea of the importance of colonial education, but by 1930, it was clear that if you were not educated in the white man’s way, you would have a longer and harder road to travel in life. His own brother, my great-uncle Orukpe, had two prominent sons in the city who weren’t farmers. The first one, Mr. Arikhan, was a tax collector in the mid-1920s for the British colonial government that ran Nigeria. The second one, Mr. Emanre, was more educated, hence his popular nickname Akonwé (the educated one), and he had a prestigious job as a forest guard in Owerri province, in the eastern part of Nigeria. These were amongst the most exalted positions for non-whites during colonialism. A forest guard would influence logging, timber trading, and general citizen extortion, as well as other revenue generation for England.

Akonwé built the first modern resplendent mansion of cement in a village of mud huts and thatched roofs. The house, atop a hilly patch on our family land, was built in 1936, according to the record in one of my father’s notebooks, which he backdated when he learnt to read and write in the late ’40s. My father told me that Akonwé brought foreigners as his masons, probably Brazilians or Sierra Leoneans who also built for wealthy folks elsewhere. When Akonwé retired, the old forest guard cultivated the same garden as the white folks, full of hibiscus flowers, croton of the most exotic colors, and other unknown species brought from the city. Older village farmers laughed. “Beauty is not edible,” they would scoff. Though Akonwé’s house is still standing after all these years, it was full of corner-cracks, black soot, and ghostliness the last time I went inside. The first modern architectural edifice in my village had also become the first ancient ruin.

Through my grandfather’s nephews, western education snaked into our village and anchored squarely in my family in the ’30s. My grandfather borrowed a page from his brother’s son and picked a child from each wife to send away to learn the white man’s “new ways of life.” The first in this experiment was my father’s eldest stepbrother, Uncle Raymond. He was sent to live with Akonwé, who as his custodian would decide which school he should attend. Uncle Raymond graduated Standard Six and worked briefly as a school teacher. In 1943, he enlisted in the 81st West Africa Division of the British Army. He was shipped off to Burma as one of the “Burma Boys,” the colonized African boy-soldiers of WWII, making him the first soldier and veteran in my village. My grandfather proudly displayed a sepia portrait of my uncle in his house.

When it was time to select who would be educated amongst my grandmother’s sons, my father was skipped. I never really asked him why, but I believe it was because he was too good a farmer to be sent away to school. It was widely believed in the village back then that only lazy kids who couldn’t withstand the sinuosity of farm work were sent to school. My father’s younger brother, Uncle Eni, was chosen in 1941 to go live with Uncle Raymond. This arrangement fell apart when Uncle Raymond was sent to fight the colonialists’ war, and Uncle Eni returned to the village and enrolled in a nearby Government School in 1943. Three years later, he established a private school where he taught my father how to read and write. Uncle Eni’s was a makeshift school of palm fronds and bamboo sticks, with classes that met beneath my grandfather’s pear tree. Uncle Eni had six young farmers as students, including my father. As with everything my father liked, he took this half-and-half education very seriously, and he began keeping the records that would eventually give birth to his archive.

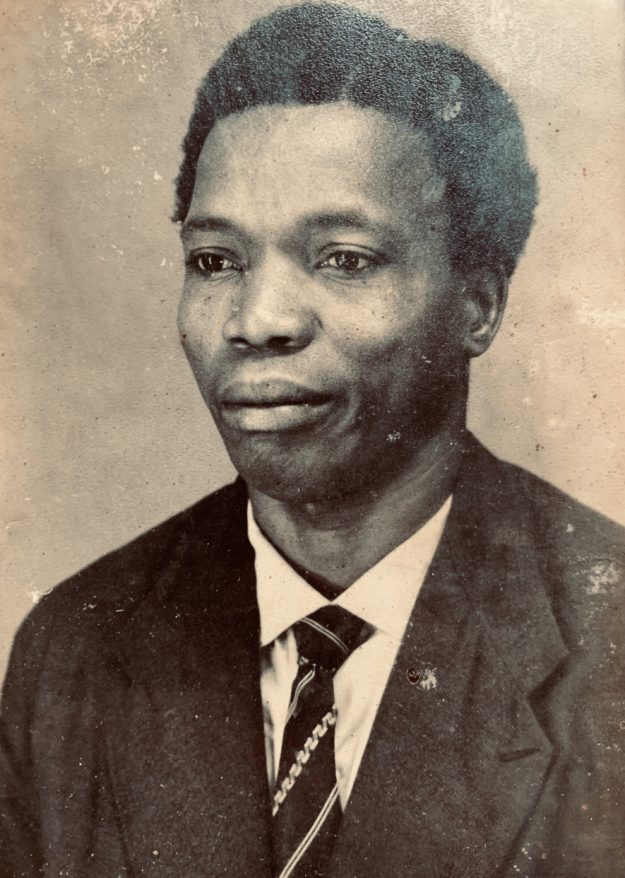

Uncle Eni graduated from Government School in 1948. When Uncle Raymond visited the village that year, he took Uncle Eni to Benin City and enrolled him in Western Boys High School, one of the most prestigious boys’ schools in the region at the time. Barely a year later, and though he had performed very well, he was withdrawn from school, the reason being that fees were too high. Uncle Raymond chose photography as a trade for Uncle Eni to learn instead. “I was a young boy and couldn’t challenge his decision. I never was happy with that decision, never, not one day.” Whenever he tells me this story, Uncle Eni, an octogenarian, always end up in tears.

By 1955, Uncle Eni had become a professional photographer, with a studio named ENIS PHOTO STUDIO in Benin City, and he sent my father albums of his photographs of known and unknown subjects and objects. It did not matter if my father knew the context of his compositions or not; Uncle Eni was showing off his new craft to his big brother. With his Yashica Mat camera, he documented the city of Benin, everyone from the royal family at the king’s palace to regular citizens on the streets. I grew up impressed by an image of Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, in a firm handshake with the regally dressed Oba Akenzua, the king of the Benin Kingdom, while a young Queen Elizabeth looks on with a smile during her state visit to Nigeria in 1956. Though we have many photos of palace events and ceremonies, this was a strange one. The Oba of Benin never shakes hands with anyone, not even his highest-ranking chief. It is against palace tradition. But the British still had their ways in the colonies, just as they did during the Punitive Expedition of 1897, all traditions and taboos violated.

Uncle Eni left Nigeria in 1961 to go for further study at the New York Institute of Photography. While in America, he wrote very sparingly to my father but sent loads of pictures of white people wearing traditional Nigerian outfits. We giggled at this spectacle of white folks dressed like they were going to a festival in my village. He was culturizing his fellow foreign students.

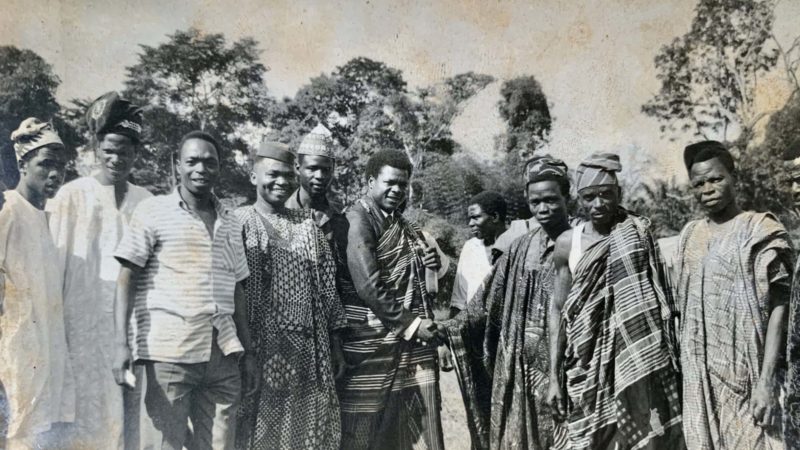

My uncle took Uwessan village to New York and, upon his return, brought New York to Uwessan village. When he returned from America in 1965, all the major newspapers in midwestern Nigeria reported the news. There was celebration upon his return because he was the first Uwessan man to go and study in America; my family and my village were very proud of this piece of history. Newspaper clippings, pictures of two traditional dance troupes performing, images of my mother and grandmother dancing with joy during the welcome ceremony in my village—all were carefully stored by my father in empty AGFA and Kodak film packets. There is a photograph of my father proudly shaking hands with his newly returned brother while other village elders surround them in a semi-circle. There is also a picture of Uncle Eni and Miss Mango, a white American Peace Corps member he came to the village with. Villagers rumored she was his wife, even though they were just friends. Sighting a white woman in my village, then or even now, is not so different from James Baldwin’s observation in his essay, Stranger in the Village: “I thought of white men arriving for the first time in an African village, strangers there, as I am a stranger here, and tried to imagine the astounded populace touching their hair and marveling at the color of their skin.”

If there had been a telephone in my village then, all I am seeing and reading in my father’s archive now would have been lost to the air. Like the records of people who borrowed money from him and never paid back. I didn’t know how much my father’s kind-heartedness expanded to others that weren’t part of my immediate family. The letters of appreciation, letters of request for financial assistance, letters asking for help investing in livestock like goats and pigs, letters pleading for help in supervising the construction of their houses while they lived away. Some of my uncles even wrote asking him to help arrange for nice village girls for them to marry, with exact descriptions of the ideal girl’s looks, family background, and “behavior.” They were not to be older than eighteen, educated up to secondary school, taller than average height. One uncle preferred a girl from a particular village, and the other was very specific on a “yellow” (fair-skinned) girl. As if these young men in the city were ordering life partners from Amazon, as if there was a warehouse in my village and my father was Jeff Bezos. In any case, some of the marriages my father arranged dissolved like salt in hot soup, while others lasted till death did them part.

A lot of information I am discovering in old letters and notebooks is new to me. For instance, the date an uncle committed suicide. I only know this now that I am reading the condolence letters sent to my father when it happened. Nobody ever described this family tragedy as suicide, although how else do you explain a man who couldn’t swim leaving his clothes by a riverbank and jumping into a fast-flowing river? My eldest sister remembered the wailing of villagers as the sound of a million bees. My grandfather was silent for many days, I was told. I was not born yet. All I can piece together in my father’s letters of this sad event is that it happened in November 1968.

On the night my uncle died, patrol soldiers guarding the streets told the search party they saw a man walking towards Ethiope River, but because he was harmless, they did not stop him even though it was wartime. Some condolence letters to my father from relatives in the city demanded explanation, as if my father was present where his stepbrother died. My uncle’s body was fished out three days later and buried in the city where he died, making him the only uncle who was not buried in the village amongst his kinsmen. There is a picture of my father and this uncle in identical farm clothes in front of my grandfather’s house, holding a big tuber of newly harvested yam like a trophy. The photo was taken by Uncle Eni, ten years prior. In any case, a few of the letters here sketchily reveal that my father was in shock and fell seriously ill when he heard the news.

At that time, the Nigerian Civil War/Biafra War was at its peak. People couldn’t go about their businesses freely in our village; farmers abandoned their farms for fear of getting killed by marauding soldiers. An aunt who lived in the northern part of Nigeria wrote home to confirm whether a bomb had landed in the center of our village and killed many people. It had not; it was just one of the numerous rumors that invaded everyone’s sanity during that war. Due to my village’s proximity to Eastern Nigeria, then Biafra’s enclave, Biafran soldiers took over primary school for a number of days, until Nigerian soldiers arrived to dislodge them. My father told me how some Biafran soldiers were hidden under empty drums by our villagers; they didn’t leave the village, even after the war ended. Oral history also has it that a certain village lunatic named De Lord was shot in the leg because he did not understand a Nigerian soldier’s command to raise his forefinger and declare “One Nigeria,” the password for solidarity and safety.

I was born the year the civil war ended. 1970.

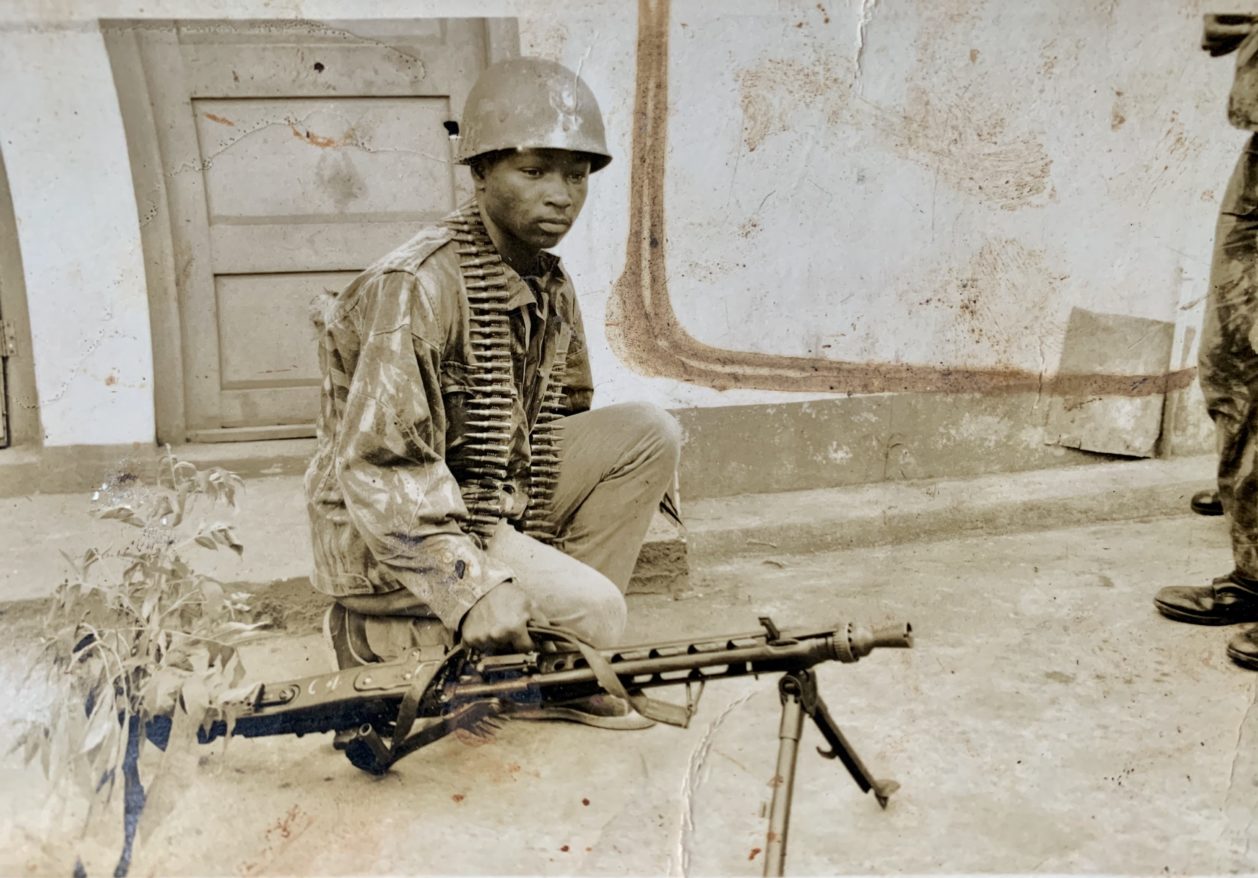

My elder brother, Osajele, who was 11 years old at the time, told me of an event of one evening, not long after I was brought home from St. Camillus Hospital. My father had gone out for his ritual evening strolls, and my grandfather’s five wives (one had passed away by then), their children both young and old, daughters-in-law, and grandchildren—including my baby self—had just finished supper when they heard non-stop multiple gunshots. Women froze in their respective positions, huddling children under their many folds. Youths hid behind doors or other shelter. My grandfather, in his parlor, urged, in a hushed tone, that everyone be calm. The commotion continued for a good number of minutes. When the ominous sound that shattered a rather peaceful evening eventually abated, Cousin Benedict burst in. My brother tells the story as if he is narrating a John Wayne film: “In full Nigeria military regalia! A smoking gun held with both hands and a necklace of bullets dangling around his neck! He busted through the front door leading into grandfather’s inner compound, shouting ‘Ivaleh o, Ivaleh o, Ivaleh o!’ I have arrived, I have arrived, I have arrived!” Cousin Benedict, my mother’s nephew, had joined the Nigerian Army as a teenager, just before the war broke out. The war did not claim his life, but he remained a broken person until last year, when he died.

Though my father did not document this gallant return from war in writing, there are photographs of Cousin Benedict at different times in his life during active service: some with his beautiful wife; others by himself in mufti, smiling; and others in full military combat fatigues, squatting next to a menacing military rifle resting on a bipod. In my father’s archive, what words didn’t record, family photographs did. And there is no photo in my father’s archive that is devoid of history told to me when I was a child. These old shriveling pieces of history are what I am feeding on, now that those who told them have departed, one after the other.

Many uncles and aunties in the letters and pictures my father kept—the people whose warm arms and smells embraced me on their arrival from the city—are now dead. Of the twenty uncles and aunties I knew then, only eight are alive today. My family’s graves are scattered across my grandfather’s large compound, the lands where they all grew up before leaving for the city. Men who did not come back home to build houses are buried in the open land instead of private rooms. Beneath the grounds I walk in my ancestral home lie the men and women who shaped me. And here in Lagos are their voices, reawakened in what still survives in these battered bags of memories kept by my father. My children, and their children, will not have this experience. Nobody writes to anybody anymore. The journaling and letter-writing that my father held in high esteem has been killed off by modernity. We either chat on the phone, or we send text messages, and our memories, exchanged, become powder in the wind.

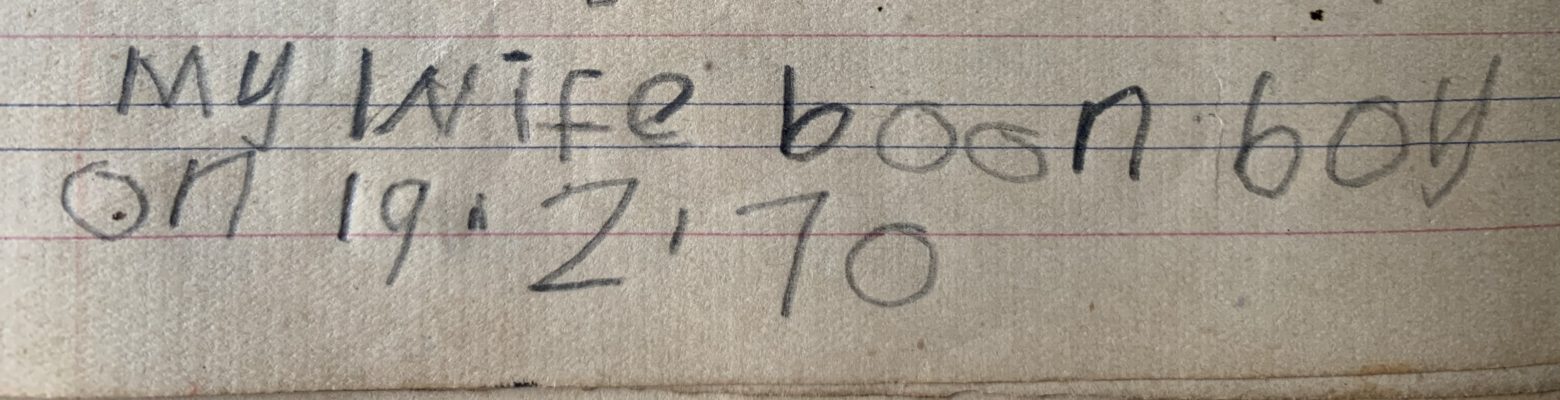

Archives, no matter how robust, are never complete. Insects eat what humans leave behind, and humans make errors in the first place. Many town and village names in Nigeria were changed by colonial officers who couldn’t spell local words. In my father’s notebooks, his children’s birth records are scattered. Our births are recorded on different pages, along with deaths. There is a birth record of a brother born on June 11, 1956. He died before I was born. I also read that my mother lost a daughter on the morning of December 29, 1953 and gave birth to another girl later that same day. How do you mourn and rejoice at the same time? The notebooks do not tell me. I know only what my father saw fit to record: “My wife boon girl. 29.12.53.”

I have taken time to carefully open every piece of paper and read through, because some things my father documented are buried in the least expected places, like my own birth record inserted between school assignments: “My wife boon boy 19.2.1970.” I found a letter from my cousin recommending that my parents name me Victor. Back then, the best slogan that Nigeria’s head of state, General Yakubu Gowon, and his cabinet could come up with for reuniting the country was, “No Victor, No Vanquish.” In fact, there were plenty of Victors, and many Vanquishes.

There is a particular short notebook in my father’s archive that’s riveting. One could call it the Uwessan Village Death Registry. In all the records my father kept, the necrographic death entries he recorded were most duteous—spanning decades. B.A. Ehikhamenor’s own death happened on August 18, 2004, and there is a poster of his obituary announcement tucked in one of his notebooks. I want to believe Uncle Eni slipped this poster in while gathering the archives together for me. Or maybe my father, thorough even in the afterlife, visited from the land of the dead to embed his own record of death amongst the others.