One risk in being a very good critic, however rare, is that one’s own judgments might become bigger performances than the art one sets out to describe. Criticism of all kinds is bounded by the assumption of a binary: There is the subject of analysis, there is the analyzer, and never the twain shall meet. Once that binary breaks down, other dangers may surface. A reviewer might get high on the power of playing gatekeeper, and start trumpeting ideology without seeing the ego involved. (William Logan is such a case, and perhaps the early Michael Robbins.) In better situations, though, the aggrandizement of the critic simply exposes criticism for what it is: creative writing, an experience that engages the head and the heart both, and that is based, like all the best writing, in passionate investment. What I really want to see when I read a good writer is that they love something—isn’t that always the point?

Hanif Abdurraqib is both a poet and a critic, and masterfully so. Although the line between his art and his writing about art is not always stark, all his work comes from an evident place of love. This may be a matter of origins: as a self-described “scene kid” who grew up at punk shows in the Midwest and became a capacious music nerd at a young age, Abdurraqib knows how to bond with a reader over the track he can’t get over, the underappreciated minor band. It is his ranging affections, his unfettered (yet still critical) enthusiasms that we come for. And clearly he loves many things. In 2016 The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, his first book of poems, was a finalist for the Eric Hoffer Book Award. The next year saw They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, a compendium of his music writing and personal essays, which made more than a dozen Best-of-the-Year lists. In 2019, he doubled up. The biography Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest was published in February, and his second poetry collection, A Fortune for Your Disaster, came out last fall, right as Go Ahead in the Rain made the longlist for the National Book Award. (It has since been named a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.) His next two books are under contract with Random House; the first, a history of blackface, will be published later this year.

It is both bizarre and a little precocious to map a writer’s career while they’re still emerging, but Hanif Abdurraqib works fast, and we’d do well to try and keep up. Although it’s easy to treat his nonfiction and his poetry as distinct career tracks, he is quickly and efficiently building a single oeuvre bound by his enthusiasms, formal tendencies, and persistent concerns. Chief among his themes is the responsibility of the performer; as Abdurraqib rises to prominence, he is forced to turn that attention on himself more and more. Looking across the four books thus far, one can track this recognition, as Abdurraqib’s self-presentation within his work becomes increasingly complex.

The best way into Abdurraqib’s writing is to recognize him as a storyteller, full stop. His attraction to songwriters, from Bruce Springsteen to Q-Tip to Pete Wentz, lies in their ability to formulate narrative particularity, to tell a story so that readers and listeners who weren’t there will feel just like they were. In Abdurraqib’s hands, both poetry and criticism can be performed by way of story. “I always loved the lens through which you placed yourself directly at the center of a story,” he writes to Phife Dawg in Go Ahead in the Rain, “not sparing yourself for the sake of narrative.” With the poem “At My First Punk Show Ever, 1998,” the opening of his debut collection, Abdurraqib literally flings himself into a scene:

me & tyler jump into the pit head first even though four older boys got patches that say NO BLACKS & NO QUEERS & I flinch & cover my head when the drum kicks too sharp & I don’t know what could be more black than that & tyler don’t know it but in an alley last month I saw him build a church in the mouth of a boy…

Abdurraqib’s language is energetic and associative. In poems, as in essays, he’ll often leverage the power of “and” to create a breathless, paratactic sprawl. The moment expands to take in multiple feelings, to call out and complicate, and to recognize all the complexities of being a black teenager in a white counterculture space where excitement, aggression, and brotherhood all merge. By the end of the poem these tensions turn to direct violence, marginalizing someone else:

…some blond girl from bexley gets slick & tries to sneak into the rampage but not before tyler & some other boy grab her by the collar & toss her smooth out & then they high five & through the guitar bending over our heads like an umbrella I hear tyler whisper some things are just unacceptable & then he puts his head in his hands…

Abdurraqib uses story as a vehicle, a means to reach moments of heightened emotion. Often they elicit complicated feelings, swirling together ecstasy, deep sorrow, world-opening grief, and great awareness. Which is to say it is the space of adolescence—of the first time you found a song and knew it was for you, of the intensity of friendship, first love, and endless summer, of a world that is both extraordinarily bleak and also redolent with promise. Appropriate to the punk and emo that he grew up on, Abdurraqib has made a principal engine out of the recreation of teenage feeling.

The emo sensibility is axial to Abdurraqib’s voice, and it’s something that he has thought through carefully. He recognizes its sentimental excesses and its limits, but can see the cathartic power that comes from making art around raw emotion.

A lot of the people I knew who dismissed “emo” while the genre was at its peak did so because they believed emotions were things that should be sacred and unspoken, not screamed out to the listening masses. I push back against that, both in personal practice and as someone who has seen the other side of that coin, or known people completely eaten alive by the hoarding of sacred emotion.

The risk of repressed feeling, to Abdurraqib, is annihilation from within. The risk in too much broadcast feeling, though, is another kind of self-involvement, or the exploitation of one’s pain for success. The taut awareness of these twin dangers animates much of his writing. In book after book, Abdurraqib hunts for ways to speak from an originating place of grief without being rendered inert by it. His first two books carefully revolve around profound losses that can only be observed at a slant: the sudden death of a mother, the suicide of a best friend. In some sense, Abdurraqib is a virtuosic elegist. All his work is born of grief. (This is most evident in Go Ahead in the Rain, which manages to be both a vivid history of early hip-hop and an extended elegy for a rap group that defined the author’s sensibility.) But even as grief rises up and speaks its own name, it is continually braided with nostalgia, with humor, and with a desire to look forward into something else. In a place of deep self-critique toward the end of They Can’t Kill Us, Abdurraqib questions his relationship to elegy: “how rarely I find myself speaking to the living. How rarely I am asking readers to imagine a world in which I am surrounded by my many living friends, family, and my deepest loves.” One thing that we can see across the four books is an increasing awareness of the risks that come with the performance of grief: what it may turn away from, or turn the performer into.

At the level of the sentence, Abdurraqib’s formal tendencies show him wrestling with feeling, how to deploy it, relish it, but not get caught in the quagmire. One of his principle linguistic maneuvers is the pithy statement of wisdom, using a declarative to make an observation feel like a universal.

It is one thing to be good at what you do, and it is another thing to be good and bold enough to have fun while doing it.

None of the shit people say feels like drowning actually does.

All heartbreak is a descendant of the untouched imagination.

The thing about fashioning yourself as an outsider is that no one can call you anything that you haven’t already decided for yourself.

Aphorisms like these are a powerful part of a poet’s toolkit—at a reading, they’re the spots most likely to get a snap or an mmm of recognition. They have the weight of truth. But they come with a risk: Because they make for very satisfying music, they can be overexerted. (This can be like someone telling you, “Look, the fact of the matter is x,” so often that you start to question if there actually are any facts, or any matter, at all.) Across Abdurraqib’s poems and nonfiction, the single most dominant rhetorical crutch is this over-reliance on aphorism. The surfeit of dazzling “truth”-statements forms a necessary counterpoint to emotional professions—they’re a kind of guardrail against sentimentality—ut the overuse of this maneuver suggests how Abdurraqib is grappling with the tension between the emo impulse and a suspicion thereof.

At the height of this suspicion, we arrive at A Fortune for Your Disaster. This new collection situates the speaker in a series of afters: after grief, after divorce, after death, after the hopefulness of the Obama years, after (but still very much trapped within) the American history of violence against black men. Abdurraqib’s newer poems are slightly cooler in temperature than those in The Crown, with more space on the page; they demonstrate a certain distance from feeling, an ability to observe and question it. Here even heroes demand deeper scrutiny. From a meditation on Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama:

show me a way to govern

without violence

and I will show you

a way to not feel

shame inside

of the moment

where one recognizes

their face

in the face of their captor

and falls in love

with the familiarity

This piece bears the same title as more than a quarter of the poems in the book: “How Can Black People Write About Flowers At A Time Like This,” which mobilizes the full apparatus of Abdurraqib’s thinking about race, art, politics, the pastoral, and black mortality. It is a question without answer, except for the answer that is the poem.

The book is architected around a surprising obsession, treating the movie The Prestige as a foundation on which to consider performance and sleight of hand. In the 2007 film and the Christopher Priest novel on which it’s based, the inventor Nikola Tesla provides a nineteenth-century magician with a technology that lets him teleport instantaneously, making his stage show incredibly successful. Only later is the cost of this spectacle revealed: At every performance the magician splits himself in two, killing his original and living on as the clone. Tesla appears throughout A Fortune in a series of poems all called “It’s Not Like Nikola Tesla Knew All of Those People Were Going to Die.” For Abdurraqib, this conceit is the central problem of the entertainer, of mobilizing one’s emotions for an audience. You have to kill a part of yourself to succeed, re-package your trauma to make art that sells.

The title A Fortune for Your Disaster, taken from a Fall Out Boy lyric, suggests the possibility of some exchange or transaction, and Abdurraqib has long been fascinated by value and certain economies: musical knowledge for coolness, art for love, trauma for success. Tesla, then, represents a Faustian bargain appropriate to the entertainer, and especially the black entertainer. America’s long history of profiting off of black pain plays out across popular music, whether it’s the exploitation of Big Mama Thornton and Nina Simone or the violent deaths of Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G.

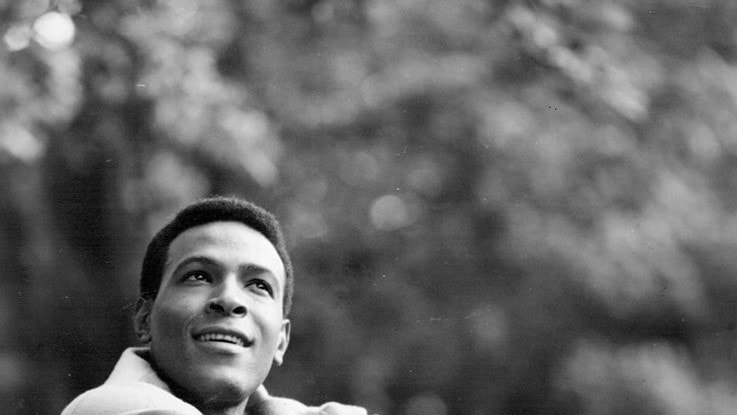

A parallel to the Tesla conceit is the myth of the bluesman at the crossroads, selling his soul to the devil for musical greatness. “It isn’t loneliness if enough tongues / have your chorus jumping / from underneath their hooded / ruckus,” Abdurraqib writes. In A Fortune, Marvin Gaye is the central manifestation of this archetype, and he returns again and again in persona poems: “The Ghost of Marvin Gaye Plays the Dozens with the Pop Charts,” “The Ghost of Marvin Gaye Mistakes a Record Store for A Graveyard,” etc. The R&B singer has long been a presiding spirit. They Can’t Kill Us uses a scene of Gaye singing the national anthem in 1983, the year of Abdurraqib’s birth, as a recurrent motif. For him, Gaye represents the complete tragedy of the black entertainer. He could sing of love both sacred and profane, caught between “What’s Going On” and “Let’s Get It On.”

Gaye’s career was marked by numerous successes and failures, and a very real struggle with the effects of fame. (He is also, quietly, one of the great artists of divorce. His album Here, My Dear, written largely to pay for alimony, is a devastating rendering of the end of a marriage, making him all the more important as a polestar for this collection.) Most importantly, Gaye’s death at the hands of his own father echoes the strange ouroboros of the performer in America. That which produced you will destroy you, collapsing backward into ancestry. “I sang that shit that could get somebody free,” the ghost of Gaye says at the end of one of his monologues. “The women all threw roses at my feet in California until the roses looked like chains.” With Gaye as tragic hero, Abdurraqib demonstrates the dark magic of entertaining. The African-American performer is caught in a transaction with a culture that wants to consume him.

With Gaye singing a warning from beyond the grave, Abdurraqib moves his work into a strange self-consciousness. No longer just a fan, the one black kid in a punk show’s pit, Abdurraqib can’t escape the recognition of his own audience, or what that audience demands of his art. He must have the double knowledge of being both performer and observer at once. As he rises to prominence, the performance of being Hanif Abdurraqib becomes a more necessary part of the pathos in his writing. This splits the sense of self—observer and observed, actor and victim, clone and cloned. He is alive, and he is not alive. In this odd bardo of his own construction, he must present and displace versions of himself over and over, in grief, in sadness, in the search for truth, all for the sake of performance.

“At some point, a person figured out that the performance of sadness was a currency, and art has bowed at its altar ever since,” he writes in his essay on Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. “Sometimes it’s a game we play: if I can convince you that I am falling apart, in need of love, perhaps I can draw you close enough to tell you what I really need.” Here the personal losses map onto the societal as well. If Abdurraqib recognizes and renders himself as a long line of dead bodies left in the wake of his art, he is also signaling black death seen in aggregate. The title of the Nikola Tesla poems, the reference to “all of those people,” has a hint of white indifference to it. As Abdurraqib the artist contends with his own responsibility, Abdurraqib the critic reminds the American audience of the pain we have come to watch—the grief and psychic violence in which we stay complicit.