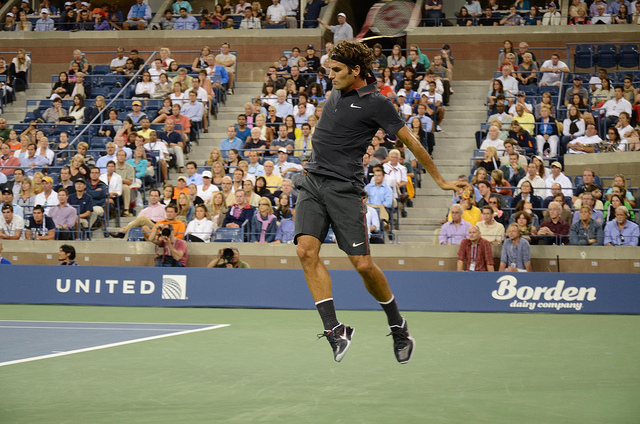

In his essay “Federer Both Flesh and Not” (originally published in 2006), David Foster Wallace argues a simple thesis: Roger Federer’s tennis game is beautiful. Since Federer is probably the most accomplished men’s tennis player of all time, Wallace’s statement might seem uncontroversial. Yet the essay finds Wallace urgently trying to put into words the nature and importance of this beauty: “Of course, in men’s sports, no one ever talks about beauty,” he writes. “Men may profess their ‘love’ of sports, but that love must always be cast and enacted in the symbolism of war: elimination vs. advance, hierarchy of rank and standing, obsessive stats and technical analysis, tribal and/or nationalist fervor, uniforms, mass noise, banners, chest-thumping, face-painting, etc… [W]ar’s codes are safer for most of us than love’s.” Conceiving of sport as war means dividing other people into winners and losers, allies and enemies. Wallace’s essay ostensibly chronicles a Wimbledon match between Federer and Rafael Nadal, but it displays little interest in giving regular score updates or announcing final results. Rather, for Wallace, the point is to appreciate the belief-defying physical prowess on display; he seems to be only half-joking when he proposes that Federer may be “exempt…from certain physical laws” that bind the rest of us.

The Federer piece is one of five Wallace essays now collected together for the first time in String Theory: David Foster Wallace on Tennis, published by Library of America with an introduction by John Jeremiah Sullivan. The release of this volume offers an occasion to reflect on the particular fascination that tennis held for Wallace, throughout his career. (Readers of Infinite Jest will remember that much of that novel takes place at a tennis academy.) Why devote so many words to an athletic endeavor? Why this athletic endeavor, specifically? A partial answer would be that Wallace played competitive tennis himself growing up, so he writes what he knows. He delves most extensively into his own playing career in the collection’s first essay, “Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley,” which recounts his unique ability to gain a competitive advantage from unpredictable weather conditions. Here and elsewhere, Wallace explains that he was a limited player, whose success came from knowing his limits and operating within them, and that his background heightens his appreciation for the unique talent someone like Federer displays. But above all else, what String Theory brings to the fore is Wallace’s understanding of tennis as an aesthetic phenomenon: Wallace upholds athletics as art form, with a function in human life comparable to that of poems, plays, or paintings. Like art critics of all stripes, Wallace worries about the uneasy relationship between tennis-as-art and tennis-as-commodity, and his writing shows him seeking anxiously to distinguish the one from the other.

Wallace suggests that the particular beauty of a sport like tennis is that it helps us reconcile ourselves to the realities of embodiment.

Understanding tennis as aesthetic phenomenon involves returning to that word Wallace insists on using in his discussion of Federer: beauty. Wallace, ever the master of precise diction, would not have chosen this word lightly, and he would have been well aware that theorizing the beautiful has been a long-standing project of Western aesthetic philosophy. In his Critique of Judgement (1790), Immanuel Kant argues that beautiful objects prompt the “quickening” or stimulation of the human mind, making us wish to linger in our contemplation of them. Given our “natural propensity to sociality,” Kant writes, we take pleasure not only in witnessing beauty, but also in communicating this experience to others; beautiful objects have the powerful ability to move individuals and to bring people together. Operating within this Kantian vein, Wallace suggests that the particular beauty of a sport like tennis is that it helps us reconcile ourselves to the realities of embodiment. Despite all the obvious disadvantages of bodies—they stink, they get sick, they die—“great athletes seem to catalyze our awareness of how glorious it is to touch and perceive, move through space, interact with matter.” Hence the uplifting potential of Federer’s game, which Wallace hears a British bus driver describe as a “bloody near-religious experience.” Tennis, of course, is not unique in its capacity to exhibit the beauty of human physical abilities, but Wallace thinks that tennis’s aesthetic power surpasses that of other athletic pursuits, in part because of it’s not a team sport: he presents tennis players as solitary artist figures, struggling to master their craft in full view of the public eye.

String Theory records Wallace’s use of another word with a distinctly Kantian flavor: genius. Like beauty, the term “genius” has perhaps fallen into overuse since the days of Kant, so it’s liable to lose some of its descriptive potency unless we recognize just how specific a quality “genius” turns out to be, for Kant and Wallace both. For Kant, the products of genius combine originality and exemplarity: geniuses do not produce art according to pre-established rules; rather, they develop new standards by which subsequent works may be judged. Of Federer, Wallace writes, “Genius is not replicable,” and he spends much of the essay explaining how “Federer’s consummate finesse” transcends the established models for how men’s tennis can be played. Another feature of genius, according to Kant, is that “the artist’s skill cannot be communicated but must be conferred directly on each person by the hand of nature.” Wallace takes up this criterion of genius to explain the particular combination of fascination and frustration that we spectators feel when trying to learn what makes professional athletes so good at what they do. Wallace develops this point in his essay “How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart,” which reflects on the contrast between Austin’s dramatic, supremely fascinating tennis career—ranked first in the world at age seventeen, crippled with injuries and basically out of tennis by twenty-one—and her trite, unmemorable memoir (containing statements like: “I immediately knew what I had done, which was win the US Open, and I was thrilled”). We buy such books, Wallace writes, because “we want to know them, these gifted, driven physical achievers. We too, as audience, are driven: watching the performance is not enough.… [W]e want to know how it feels, inside, to be both beautiful and best. (“How did it feel to win the big one?”). What combination of blankness or concentration is required to sink a putt or a free throw for thousands of dollars in front of millions of unblinking eyes? […] Explicitly or not, the memoirs make a promise—to let us penetrate the indefinable mystery of what makes some persons geniuses, semidivine, to share with us the secret and so both to reveal the difference between us and them and to erase it a little, that difference.”

Of course, Wallace points out, it’s unrealistic to expect that people who use their bodies in such unique ways will also be able to put their ability into words; as Kant has suggested, and as post-game interviews regularly confirm, that’s not how genius works. And Wallace’s essay goes one step further, proposing that the particular genius of elite athletes may actually be inseparable from the verbal reliance on clichés and truisms.

Wallace’s essays betray a constant awareness of how market dynamics intrude upon the experience of watching tennis.

But these Kantian echoes are only part of Wallace’s tennis-focused aesthetic theory. For, in contrast to Kant’s more ahistorical account of aesthetic experience, Wallace asks us to understand tennis in the context of late capitalist consumer culture, under which aesthetic innovation increasingly operates as a marketing tactic. In her book Our Aesthetic Categories (2012), the literary critic Sianne Ngai argues that—in a world of YouTube and banner ads, a world Wallace’s writings from the ‘90s already anticipate—“aesthetic experience, while less rarified, also becomes less intense.” When we are constantly saturated with sights and sounds that vie for our attention, it becomes more difficult to appreciate the truly distinctive originality that Kant terms genius. Moreover, Ngai writes, since our contemporary experiences of novelty are so bound up with capitalist pressures to buy and sell, these experiences remind us of the stark social and economic inequalities “underlying the entire system of aesthetic judgment and taste”—a point that Kant’s theory of beauty’s unifying function does not adequately take into account. As such, Ngai finds that contemporary aesthetic experiences are more likely to generate ambivalence than they are Kantian awe.

Wallace’s essays betray a constant awareness of how market dynamics intrude upon the experience of watching tennis. Thus, String Theory, a collection of essays on tennis, devotes a great deal of space to discussing things that are not tennis. Wallace describes the prominently displayed names of the Canadian Open’s corporate sponsors (“TANDEM COMPUTERS/ APG INC., BELL SYGMA, BANQUE LAURENTIENNE…”); his frustrated attempts to receive free Colombian Coffee from US Open concessions stands (“90% of the time the concessions stands would claim to be mysteriously ‘temporarily out’ of Colombian Coffee, so that you ended up forking over $2.50 for an over-iced cup of Diet Coke instead”); the controversy around “guarantees” for top players (“the less established and prestigious a tournament, the more it needs to guarantee money to get the top players to come and attract spectators and media”); and his exposure to a wide range of legal and extra-legal transactions (“I have, e.g., in the last twenty minutes received three separate solicitations to buy pot”). In their structure, the essays tend to mimic the viewing experience Wallace wants to convey: they often begin by describing tennis, then shift to recounting various attempts to profit off tennis, which surround and blanket the tennis so tightly that—ironically enough—it becomes increasingly difficult to focus on the game itself. Wallace’s essays show, then, that tennis is unavoidably complicit in capitalist consumption and exploitation. But he also maintains that, within this context, its aesthetic power becomes all the more striking; it remains “beautiful” in a culture that, according to Ngai, finds this term outdated. Its beauty simultaneously resists and enables its marketability.

In our hyper-corporatized contemporary society, rife with ironic detachment, Wallace endeavors to put genuinely moving aesthetic experiences into words.

One of the advantages of String Theory is that, by bringing these five essays together, it highlights how each one makes a distinctive contribution to Wallace’s vision of tennis as aesthetic phenomenon. The collection shows Wallace sketching out a spectrum of physical artistry, a spectrum that runs from not genius (almost all of us spectators, including—in the realm of athletics, anyway—Wallace himself) to genius (Federer; Austin). Via his profile of Michael Joyce—the 79th ranked men’s tennis player in the world, at the time Wallace covers him—Wallace emphasizes that Joyce is much, much closer to the Federer level than he is to the regular person level. Joyce has devoted his entire life to the pursuit of athletic excellence: “he really has no interests outside of tennis”; he has “consent[ed] to live in a world that, like a child’s world, is very serious and very small.” For all this effort, Joyce has to participate in pre-tournament qualifying just to make it into bigger professional tournaments. Participants in these “Qualies” need to reach the main draw to get their room and board reimbursed, so some of them are “literally playing for their supper,” baldly confronting the fact that their undeniable talent only barely enables them to make a living. (This is not to say that top players are immune from financial injustices: for instance, Serena Williams, about whom Wallace unfortunately did not write, earns less from endorsement deals than many other, less accomplished athletes do.)

Wallace’s essay portrays Joyce as a player of rare talent, an artist…but not a genius. He simply does not have that elusive quality that will make him a model for generations to come—that quality that Austin had, that Federer still has, and that Wallace seeks to describe. Coming out twenty years after the publication of Infinite Jest, String Theory shows that Wallace’s tennis writings are of a piece with his broader literary project. In our hyper-corporatized contemporary society, rife with ironic detachment, Wallace endeavors to put genuinely moving aesthetic experiences into words. He thereby encourages us to appreciate beauty—in whatever form it takes.