No one knows how, in 1942, a tiger came to be on Hong Kong Island. Some argued it was a circus escapee, freed during the Japanese invasion when a bomb blasted a hole through its paddock. Others pointed out that it might simply have swam across Victoria Harbor from mainland China. It wouldn’t have been the first: tigers were a rarity in twentieth-century Hong Kong, but hardly the stuff of fiction.

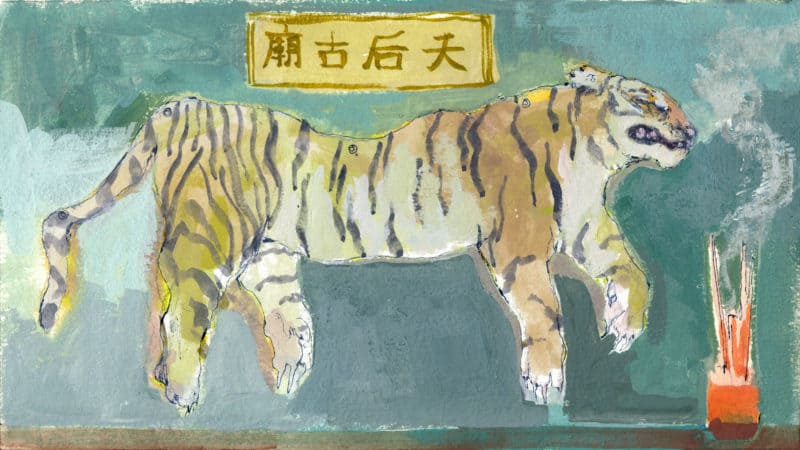

However it got to Hong Kong Island, it never got off. Police shot the young male dead, its fulsome orange-striped body reduced to a ratty gray skin that still hangs in Tin Hau temple. In the decades since, the South China tiger (Panthera tigris amoyensis) has become one of the world’s most endangered animals.

Tigers had always been an occasional—if potent—presence in the New Territories, a large swath of the mainland and several islands adjoining China’s Pearl River Delta. It was not so long ago when, in 1915—after being dispatched to investigate what were thought to be spurious local reports—British policeman Ernest Goucher and Indian constable Ruttan Singh were mauled to death by one such cat near Fanling. Unconfirmed accounts of (and injuries by) tigers continued into the mid-twentieth century, when, in an all-too-common refrain, the animal faded into memory.

Before the 1950s, some four thousand tigers roamed throughout southern China’s provinces—more than the total number of wild tigers, of all subspecies, alive today. Then, during the Great Leap Forward, China’s havoc-wreaking industrialization campaign, tigers were declared a “pest” and their numbers plummeted. Those that straggled on into the later twentieth century were picked off by poachers capitalizing on an increasingly lucrative trade in tiger skins and bones, which to this day are flaunted as status symbols and used in traditional medicines.

The South China tiger may not be gone yet—a confirmed sighting in 2007, in the northern Shaanxi province, offers some hope that a healthy wild population might be restored. But in Hong Kong, where I live, tigers are gone.

I think about them sometimes, returning home alone and at night. A ten-minute walk from the train and the world of concrete ends abruptly in a narrow, pedestrian-only path, which skirts the edge of a marsh and winds through a clutch of bamboo forest. Dense and laced with jungle creepers, humming with insect life—in times past, it offered ideal concealment for a big, hungry cat. So maybe, if only for my own sake, I shouldn’t miss them.

I do anyway. We so often gauge nature’s vitality by the presence of outsized, charismatic species like tigers, the kind that lend themselves easily to children’s book illustrations and magazine covers. These animals are emblems of all the other life, from tiger- to insect-sized, that is no longer here. Absence is perhaps the most common condition of the Anthropocene, this epoch in which humans have irrevocably altered the face and future of the planet. In urban and undeveloped environments alike, we are haunted by a spectral presence of vanished nature: those organisms that, because of us and despite us, aren’t coming back.

With its location in China’s Pearl River Delta and a population of more than seven million, considered the world’s greatest megacity, Hong Kong is not an ecologically sustainable place. Pollution is rife. The air quality is nearly three times worse than that of Los Angeles on an average day; sometimes, when high pressure and a shift in the airstream traps pollutants, it can be even more severe—more than double that of Beijing and Delhi. The average citizen’s daily waste output is twice that of people living in Singapore and Tokyo, and approaches nearly 70 percent that of the average American (the world’s most rapacious consumer). Some 90 percent of Hong Kong’s food supply is imported, and only 2 percent of vegetables are produced locally. It can feel a bit precarious.

Just a few hundred meters from my third-floor flat, down through the old tiger forest and around the marsh, is a mall with a wildly popular IKEA: Sundays are marked by minutes-long barrages of honking that erupt from the line of cars awaiting entrance to the parking garage. Beyond the mall stretches Sha Tin, a district of more than 600,000 people housed mostly in thirty-story tower blocks. The majority of these actually stand on land reclaimed from the estuary, the remnant of which has been reduced to a heavily contaminated “river.” But if you look at old pictures of Sha Tin, it appears as a vast bay lapping the feet of precipitous, jungle-laden mountains, with small clusters of villages nestled in the folds of their great hemlines.

The house where my wife and I live is in one such village, on a small bluff overlooking a gully, an unbroken draw of subtropical forest that wends around homes, monastery, and housing development, up to one of Hong Kong’s protected country parks. This acts as a kind of corridor for wildlife, which, despite being so close to Sha Tin’s sprawl, carries on in extraordinary abundance.

The city’s proximity to sweeping expanses of untrammeled nature is striking. Almost three quarters of the territory is undeveloped, while a full 40 percent is designated as country park. While the outskirts of most cities feature a steady fade from urban center to suburb to village, in Hong Kong the city just ends—and the terminally green forest begins.

As a recent migrant to Hong Kong, I was startled by the first pair of furry, thin-tailed rumps I saw vanish into the brush outside my front door. Wild boar like these, it turns out, are quite common. In the cooler months around dusk, they appear frequently in the small forest clearing down from our front door, and we can hear the grunts and squeals of their negotiations late into the night. Another animal’s call can sometimes be heard around that time, too: a rasping bark, of a puzzling timbre distinctive from the village’s dogs. It kept me guessing until, one evening, the unlikely culprit emerged as a small, russet-colored deer with broad, leaflike ears. The muntjac, or barking deer, is widely distributed throughout Southeast Asia but tends to be reclusive; only twice have I glimpsed one in the forest clearing, before it spotted me and dashed into the foliage. I’m still waiting to see a civet and a leopard cat.

One creature that allows for very little mystery is the rhesus macaque. After the original population went extinct, this red-faced, red-reared monkey was reintroduced in 1910 for the purpose of controlling the toxic strychnos plant, which it digests harmlessly. In the absence of natural predators the monkeys have thrived, and some two thousand now inhabit the forested hills from Kowloon up to Tai Po. They are, at best, unpredictable neighbors. Their frequent assaults on the rubbish bins strew the walk up to my house in trash, they pinch vegetables from gardens, and if you’re not careful they’ll make off with your sack of groceries. Like humans, their taste for mischief extends beyond the needs of their stomachs. Hearing a ruckus, I’ve run up to our roof and found the drying laundry thrown on the ground, one monkey swinging from the clothesline and another pulling the leaves off a potted plant.

At all times of year the forest is anything but silent, and the shifting appearance and retirement of varied birds, insects, and amphibians heralds changes in temperature and precipitation. Spring is my favorite. Up on the roof at night, the industrial babble of cars, trains, and air conditioners, of airplanes droning across the sky, is drowned out by the hum of crickets in their nightly symphony. A bird cackles in the tall bamboo. From down below a monkey brashly proclaims its dissatisfaction with a boar, whose angry response initiates a minor conflagration. And a cadre of bullfrogs has camped out in a drainage under a concrete bridge, where, as from a bandshell, their belching calls are magnified throughout the ravine, a steady harmony that endures until dawn. Hong Kong is the first place I’ve had the pleasure to mark the seasons by sound.

Despite the raucous showing at our little house on the hill, like just about everywhere else Hong Kong has experienced a punishing loss of biodiversity. Alongside tigers, gone are the leopards that used to thread their own secret trails through the forest. Asiatic black bears, dholes, and the aquatic dugong are all extinct from the region, Eurasian otters are barely hanging on, and the Chinese pangolin is critically endangered. Most iconically, the local population of Chinese white dolphins (which in Hong Kong are famously pink) numbers around only sixty individuals. In the face of increased water pollution, shipping traffic, and with one of the world’s longest bridges nearing completion, it’s likely they’ll soon be seen only in the images on brightly colored tourist postcards—sad apparitions of the ghosts of nature past.

In her Pulitzer Prize-winning 2014 book The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert describes the disappearance of varied organisms as a way to understand our current catastrophe: the earth is hemorrhaging species at a rate not seen since the dinosaurs’ disappearance 65 million years ago. Kolbert chronicles habitat loss, overexploitation by humans, invasive species and diseases, and shifts in the climate and ocean acidity—all stressors presently decimating the majority of the world’s organisms—alongside stories of how the golden toad, the great auk, and the American chestnut (among many others) have vanished.

Throughout, Kolbert underscores that in our planet’s history, no creature has had such a direct hand in evolution as Homo sapiens. In this, she writes, “we are deciding, without quite meaning to, which evolutionary pathways will remain open and which will be forever closed.”

While it’s hard to pinpoint just how fast this sixth, human-generated extinction is progressing, scientific studies regularly make headlines with appalling statistics that help illustrate its magnitude. An oft-cited 2016 report from researchers with the World Wildlife Foundation and the Zoological Society of London found that between 1970 and 2012, 58 percent of the world’s animals—not species, but the sum total of creatures, or “biomass”—disappeared. We’re on track to see that number rise to a full two-thirds by the end of this decade. Using a different measure, a 2017 study published in the peer-reviewed Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that within a sample of 177 mammal species, each had experienced a constriction of at least 30 percent of its historic range, while nearly half had seen 80 percent or more of their habitat lost to human expansion since the year 1900.

While virtually every animal species is experiencing population decline as a result of human civilization, a growing minority can no longer withstand it. The twentieth century alone saw the disappearance of 477 vertebrate species, an increase of eight to one hundred times the normal, “background” extinction rate. Other estimates have placed the current extinction rate for vertebrate species up to one thousand times background levels. Right now, one in five species is facing extinction, and by the end of the century, that ratio is set to reach one in two.

Leaving aside these number games, each of us might try a simple exercise: On any continent, in any size city, walk out your front door and count how many animals are no longer there.

In the 3.8-billion-year game of survival, an organism’s most promising evolutionary “pathway” lies in its ability to exist alongside humans. And arriving at anything like symbiosis between people and wildlife requires navigating conflict.

In recent years, Hong Kong’s wild boars have been venturing into—and well beyond—the urban periphery. The largest (remaining) land mammal in the region, the pointy-snouted, shaggy-haired boars can reach a weight double that of the average man. And like all pigs, they’re clever. Not long ago, boars on the island of Kau Sai Chau found that its public golf course nurtured excellent foraging possibilities, and they seemed to share their recommendation with their mainland friends; soon boars were swimming over, circumventing a 25-kilometer (15mi) electric fence to tear up the grounds in search of fungus. But even these intelligent animals often get disoriented as their habitat is increasingly eroded by housing developments. One unfortunate boar even wandered into a mall and wound up in a children’s clothing store, knocking over mannequins and getting trapped inside a changing room (before being briefly catapulted to social media stardom by excited shoppers).

Monkeys, in turn, seem to sow more fear and confusion than they suffer from. Emboldened by years of illegal feeding—and their intrinsic simian impishness—troops are increasingly known to surround hikers and demand their lunches by show of teeth. Amusing as these rascals may be, the increased reports of conflict with Hong Kong residents represents a curious evolutionary response to urban development by one of nature’s more adaptable creatures: conflict with humans has become a successful foraging strategy.

Hong Kong’s animal issues can look quaint alongside those faced by other large cities. Consider the leopards of Mumbai. In the midst of 20 million people, the highest concentration of leopards in the world live in Sanjay Gandhi National Park, which carves out an oblong slice of the city’s peninsula. The leopards have always been there, of course, but as humans settled the surrounding land, their behavior and diets have shifted to accommodate their erstwhile neighbors. Along with living in atypically close quarters, most of the leopards’ subsistence comes from human-related fauna. Feral dogs, domestic pigs, goats, and cats, which are either kept by humans or feed off their refuse, comprise up to 90 percent of their diets, an impressive adaptation to newly urban environs.

Remarkably, there has been no relocation program seeking to remove leopards from Mumbai. Instead, humans themselves have learned to adapt. It hasn’t been easy: with the increased density of housing all along the park’s perimeter, and around a quarter-million people living within its boundaries in informal settlements, almost two hundred leopard attacks have been recorded in the last twenty-five years. But since the government devised better management policies and locals have gotten used to taking precautions—like keeping small children inside after dark— attacks have become infrequent.

Reintroduced leopards would undoubtedly thrive in Hong Kong, with its vast forests and abundant boar and muntjac, as they likely would in many cities around the world. It’s less likely that people would accept them. But as our cities consume ever more of the countryside, we need to ask if we’d rather adapt ourselves to living alongside such creatures—or, as we have with tigers, adapt to losing them forever.

While organisms everywhere are learning to live alongside humans, nowhere is the human hand in evolution more apparent than in the emergence of hybrid animals. In eastern North America, a genetic admixture of coyote, wolf, and dog has become so prevalent—and so successful—that many argue it represents a new species. When forest-going wolves were extirpated from most of middle North America, the plains-going coyote could not fill their niche. Yet the eastern coyote (Canis latrans var.), often popularized as the “coywolf,” has seemingly skimmed the best of the canine world to accommodate heavy urbanization. At home beneath open sky, dense trees, and perhaps most importantly, tall buildings, it now numbers in the millions.

Interbreeding between species typically occurs when a sexually mature individual can’t find a suitable partner. It’s likely that wolves, depopulated by hunting and habitat loss, sought coyote mates between 150 and two hundred years ago in the Great Lakes Region. The resulting offspring pushed east, where at some point large dog species such as German shepherds entered the mix. Today most eastern coyotes reflect about a quarter wolf DNA and 10 percent dog, which has dramatically expanded the scope of their predecessors’ habitats and diets. Eastern coyotes raid vegetable gardens, capture small game and hapless pets, and, like wolves rather than solitary coyotes, have started hunting whitetail deer in packs. And they can do it just about anywhere: at least twenty inhabit New York City.

When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, he noted that it was impossible to track the emergence of a new species. But as with virtually all features of the Anthropocene, speciation is speeding up. In an even more arresting instance of hybridization resulting from human-generated pressures, polar and grizzly bears have started mating. Sightings and a confirmed specimen shot by an Inuit hunter in 2016 suggest that the hybrid, dubbed a “grolar” bear or “pizzly,” is a symptom of increasingly shared ranges—and is perhaps the first real offspring of climate change.

Grizzly bears, heading north to cooler temperatures and taking advantage of prolonged seasons of vegetative growth, are meeting polar bears trapped on land by the retreating sea ice. An international symbol for the global rise in temperatures, polar bears rely on Arctic sea ice to hunt seals, which they catch by stalking their breathing holes. During summer, when the ice retreats, bears caught on land survive by coasting on their fat reserves until the ice returns. But the ice hasn’t been returning. Images circulating on social media of emaciated polar bears are but one illustration of the Arctic’s bleak future; in the evolutionary course of preserving their own, it’s not unlikely that polar bears will continue seeking out grizzly mates.

But even in the Anthropocene’s radical acceleration of natural processes, speciation takes time. What’s more likely is that polar bears, faced with the imminent collapse of their habitat, will be genetically subsumed into neighboring grizzly and Eurasian bear populations, in a way not unlike how most humans retain relict bits of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA. But then, like the cousins of Homo sapiens, polar bears will disappear, too.

One way or another, everything comes back to climate change. It is the defining event of our time and maybe our species, and we’re still only beginning to understand what it means. The prospect of polar bears’ extinction may feel remote—they’re not even officially listed as endangered yet—but this animal’s story gives us a clearer picture of just how near the future is.

The Arctic sea ice polar bears depend on is in precipitous decline. Measured at its minimum annual level, ice coverage has dropped by 50 percent in the last thirty years, while in volume it has declined by 75 percent, with NASA recording the lowest levels of ice on record in 2016. At this rate the Arctic summer may be entirely ice-free by the year 2040. And while polar bears present a compelling face to the crisis, the reality is that all of us—plant, animal, human—rely on the ice to regulate the planet’s climate. As global temperatures have warmed, the jet stream, held in check by the arctic ice, has started behaving irregularly, slowing down and wandering off track. Capricious invasions of warmer climates by colder air (and vice versa) have been conclusively linked to extreme weather events, among them record snowfalls in Europe, astonishing heatwaves in Russia, and oversized storms like Hurricane Sandy—mere previews of what will become commonplace.

During the most recent extreme event, when twin hurricanes slammed the Caribbean and coastal United States at the end of last summer, there was a lot of talk about the Paris Agreement. The first international climate accord to be almost universally endorsed since the Kyoto Protocol, the Agreement’s signatories aim to lower greenhouse gas emissions in order to hold levels of warming to “well below” two (and “pursue” 1.5) degrees Celsius, the maximum increase in temperature before, to put it reductively, all hell breaks loose. After the US and China—together accounting for nearly half of global emissions—each agreed to ratify the Agreement in December 2016, media worldwide celebrated the restoration of ecological equilibrium. Then, in June 2017, the Trump administration withdrew.

But in the ensuing media furor and political grandstanding, it was easy to forget: the Paris Agreement was never a climate change panacea. No binding mechanism holds each country to its determined contribution, and the commitments demanded by the Agreement cannot even achieve its basic goals. If every signatory reduced emissions by the mandated amounts, global temperatures will still warm to at least 2.7 degrees Celsius by 2100. The gates of hell are already loose at the hinges.

The Agreement and its discussion in global media shows how unwilling we are to address the philosophical underpinnings of what caused the climate—and biodiversity—crisis in the first place. Amitav Ghosh describes this well in his 2016 book The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, when he writes that the Agreement refuses to acknowledge “that something has gone wrong with our dominant paradigms.” The doctrine of “perpetual growth,” in which every country relentlessly pursues a growing GDP and every individual the latest in consumer goods, is integral to the Agreement, while its side effects—socioeconomic inequality, the destruction of the natural world, the sixth extinction—are willfully unaddressed. This isn’t blindness; the Agreement was designed to sustain unfettered economic growth, even though it was the heedless acquisition of capital that produced the climate crisis. At this terminal juncture we can no longer do without profound, collaborative action to halt the use of fossil fuels and invest in renewable energy. But as Ghosh observes, so long as there’s a profit to be made, our capacity to delude ourselves is boundless.

We’ve forced every other organism on Earth to adapt to us or die. Now, in a case of what is either deep irony or cosmic justice, we have forced ourselves to the very same brink.

Our relationship to wildlife has changed drastically in just the past few decades. The shoot or tame mode of what we called civilization, which decimated large predators, megafauna like the rhinoceros and American bison, and the forests, plains, and hills that were their habitats, has assumed a distinctly uncivilized pallor. The popular turn worldwide toward preserving and nurturing what nature we’ve yet to destroy is definite—and heartening.

With a one-third decline in the African elephant population from 2007-2014 and much official foot-dragging, grassroots international pressure has at last forced major countries to ban the ivory trade. After mutual agreement saw the United States and China outlaw all ivory sales in 2016 and 2017 respectively, this past February Hong Kong’s legislature finally voted to phase out the city’s ivory commerce, with a full moratorium taking effect in 2021. In the face of overwhelming public demand, the United Kingdom—the world’s biggest exporter and one of the last key holdouts—looks set to follow suit. These are crucial victories, which speak to a cross-cultural desire to bring extinction to a halt.

Yet popular demand rarely translates to legal action. The decades-long battle for governments to band together in stopping the ivory trade, still unfinished, can look meager next to the effort required for organizing around anything like a global carbon tax, or an international fisheries management plan, or a way to stop the razing of the world’s rainforests. As an international community we’ve never been more aware of ecological crisis, and have never poured so many resources into environmental protection—but most of us are powerless to do much beyond taking our humble stands as we watch the world’s wildlife disappear.

Why does biodiversity matter? Plenty say it doesn’t, claiming that we humans will get along just fine without a full spectrum of organisms. This is a dangerous assertion, as the environmental analyses of the past few decades are hardly enough to assess ecosystems that took tens of millions of years to develop. There is so much we don’t know. We don’t know for sure yet how the collapse of bee populations and other insect pollinators will affect our food supplies. We don’t know where the world’s coastal communities will turn after the strip-mining of the world’s oceans. We honestly can’t imagine a world without polar bears. But these concerns are just as anthropocentric as the reckless dismissal of biodiversity. We should really be asking whether that’s the kind of world we want—one that is for Homo sapiens alone, this most privileged and cynical of species.

Even if the answer is yes, the rest of the world’s creatures are not going to sit back and accept it. On our rooftop not long ago, my wife and I were visited by the alpha male of the local rhesus monkey troop. We had encountered this forbidding, heavily muscled fellow before on the path home, where he’d stood guard over females with infants. This time he was alone. He climbed up the drainpipe and swung lightly onto the rooftop bannister, where he did a languid about-face, revealing a bright scarlet rump and menacingly weighted testicles. The two of us stopped speaking and stared as he strolled across the bannister and leapt onto the stairwell’s concrete vestibule, blocking our way back inside. He never gave us a glance, but it was clear he knew, with his inch-long canines and raw physical brawn, that he had our fullest attention. For a good five minutes he sat gazing out upon the forested ravine, ignoring our whispered and somewhat anxious exchange. Then he got up and returned nimbly the way he had come.

For all the tigers that have vanished from Hong Kong, these monkeys have only prospered, finding an evolutionary niche in the gash wreaked by humans. This one’s message was clear: This is my rooftop, too. There was nothing spectral about him.