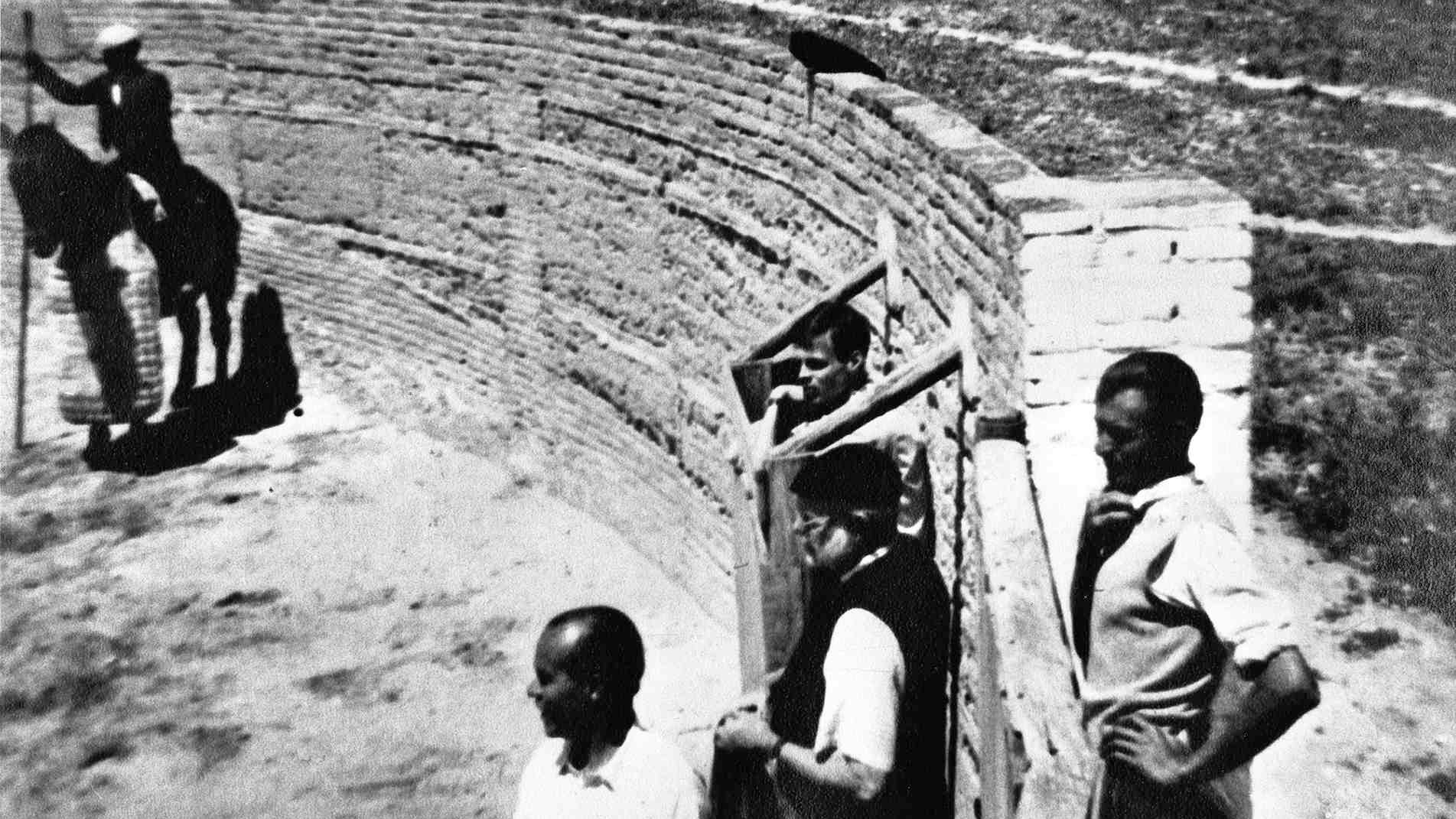

In early 1959, George Plimpton was preparing to watch an execution in Cuba. The Cuban revolutionaries, led by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, had just marched on Havana and ousted the US-supported dictator Fulgencio Batista. The young Paris Review editor and other New York literary figures arrived during a period marked by hope for a democratic Cuba. They were there, too, as witnesses. Wary of US media distorting events, the revolutionaries had called in writers and intellectuals to witness the changing of the guard.

The changeover involved infamous trials—and even more infamous executions—that had become increasingly controversial. Guevara had witnessed an earlier coup in the region, in Guatemala, and calculated that it had been possible only because the country’s new leader allowed military officers loyal to the imperialists to remain in their posts after the election. Fearing a similar US-supported rollback, Guevara insisted the war criminals who had done the dictator’s bidding must be tried, read an accounting of their crimes, and summarily executed.

In some versions of what happened next, it was Hemingway who, leisurely sipping tequila sunrises, took Plimpton to watch the prisoners offloaded from trucks and shot. In other versions, Hemingway stayed home and it was Plimpton and the other visitors from New York who viewed the shootings as entertainment. Regardless, the event marked a high point in Plimpton’s long cultivation of a friendship with Hemingway, which he had initiated with an interview request—the acclaimed author declined, cursing wildly—six years before. The interview nevertheless appeared in the famously apolitical Paris Review, which syndicated it around the world to literary magazines funded by the CIA’s Congress for Cultural Freedom. The Paris Review offered it to the CIA’s literary family without Hemingway ever being told, and Plimpton quietly joined, however indirectly, the chorus of pundits, bureaucrats, and friends who politicized Hemingway’s home in Cuba when it had become politically taboo to live there. Not long after Hemingway returned from the island, his discomfort living in the nation of his birth, and the government’s relentless surveillance of him there, would lead to his suicide.

“Hemingway himself is an outrageous old man,” Plimpton wrote William Styron in 1953, proposing the interview to his co-editors during The Paris Review’s launch. “I met him in the Ritz bar where he agreed to give us an interview…. His language is what you’d expect, and I should guess the most difficult problem of the interview would be to tone it down…. He is in Kenya at the moment, adding some Mau Mau filth to his vocabulary…and will be back here in November.” If this progress report sounds less than adulatory, it may have been tongue-in-cheek bravado; gradually but emphatically, Plimpton came to idolize Hemingway. More likely, it pointed to the abuse that Hemingway doled out to the upstart editor, both verbal and physical.

In his first written response, Hemingway attributed his reluctance to be interviewed to injuries sustained after a pair of plane crashes in Uganda in early 1954. In a string of very bad luck, his touring plane went down, then his rescue plane caught fire and crashed. He was understandably ornery.

My temper is a little bad from a slight surfeit of pain. I truly never mean to be rude ever but…I cannot talk like Forster, nor Graham Greene, nor [Irwin] Shaw and I might say fuck the Art of Fiction [though] what I would really mean was fuck talking about it. Let us practice it and shut up.… My experience has been that when a writer talks about himself and his work except with his girl or other writers or to try to straighten kids out with whatever you know that can help them he is usually through, or a poseur or more or less a pompous ass.

Undeterred, Plimpton found a way to Spain to catch Hemingway during his annual visit to run with the bulls. He wrote to his colleagues: “I had a most splendid time in Pamplona…but I received the worst of it in the amateur [bull] fights, getting myself tossed and tromped on. I was carrying a furled umbrella at the time (someone had given it to me to hold) and the incident—while humiliating and painful to me—caused great merriment to 15,000 people and presumably one cow.”

Plimpton was a pioneer of a wing of New Journalism that some have taken to calling participatory journalism. He was also a serial exaggerator. This combination of qualities charmed friends, fans, and readers alike—on the page, on television, and while entertaining guests at his legendary cocktail parties. As a writer, Plimpton admired the reporting of Paul Gallico, who believed that you should hardly write about sports until you enlisted to pitch against professional baseball’s sluggers or stood in as quarterback for the Detroit Lions. Both of these Plimpton famously did. Plus he went on safari, played goalie for a professional hockey team, jumped from a plane, did stand-up comedy, played a bit part in a John Wayne Western, became a trapeze artist, and played triangle for a world-class New York City symphony orchestra.

Throughout, short-form or long-, he wrote about it. Was it just a coincidence that this editor, whose magazine would help the CIA distribute positive propaganda around the world, spent a career writing pieces that celebrated American pastimes? Was it merely a matter of Plimpton listening to determine what was in harmony (and funded by), and what was discordant, with the music of the Cold War?

Whatever Gallico’s influence, the letters between Plimpton and Hemingway make it clear, too, that Hemingway’s heroism also left its mark. Plimpton was using not just the interview to maintain contact with the novelist but also his participatory writing. Plimpton’s sports writing could at times be gimmicky, managing to appear both self-flagellating and self-obsessed. He clearly had less personally at stake in some of his “stunts,” as he called them, than others. His more acclaimed literary friends tended to view the participatory writing as downright silly and unserious. James Salter said that Plimpton’s participatory journalism was “a genre that really doesn’t permit greatness.”

But Plimpton used it in such a way—asking Hemingway for help finding a boxing coach, seeking his advice when his editor wouldn’t let him print the athletes’ curse words—as to fold the novelist and man-of-action into the lore of The Paris Review, its blue-chip canon of author interviews (alongside the party hoppers and other outsized personalities), and to enwrap the canonical writer into Plimpton’s own legacy. He appeared to be having a great deal of fun.

When Hemingway wasn’t mercurial and cranky, he could ooze with praise and even occasional earnestness. In blurbing Plimpton’s baseball book, Out of My League, he called Plimpton the “dark side of the moon of Walter Mitty.” And it exercised him that Plimpton wouldn’t be allowed to record the real color of conversations around the baseball diamond, when the publishers wouldn’t print the players’ colorful dialogue in full. Papa, as his admirers called him, could cuss—e.g., “fuck the Art of Fiction”—and the anger and frustration embedded in American dialogue were an indispensable component of his own literary technique. Plimpton won Hemingway over with charm and persistence. Courage was essential to the participatory journalist, and as he fought championship boxers or played quarterback with professional football players, Plimpton found that the comic form of the amateur against the professionals barred his success in a given game or match, while at the same time lowering expectations enough that he could triumph just by having shown up—so long as he survived. Plimpton’s bungling among the pros flattered both the amateurs reading in their armchairs and the experts, as Hemingway fancied himself, and often was. At the height of their bonding, they became friends, and Hemingway encouraged Plimpton more than Plimpton’s own father, who had dismissed the first issue of The Paris Review as “exhibitionist” and could be a severe disciplinarian and scold.

Plimpton’s Hemingway interview and their subsequent friendship were themselves part of this participatory experiment. One wrong move in the acolyte’s attempt to immerse himself could be painful. On one of Plimpton’s Cuba visits (and contradictory claims make it unclear if there was more than one), Hemingway famously decked him over an impertinent question (“What is the significance of those white birds that sometimes turn up in your, ah, sex scenes?”). Hemingway may have seen it as part of Plimpton’s belated training. Plimpton shared Hemingway’s interest in boxing and had fought the light-middleweight champion, Archie Moore, in early 1959, as one of his writing stunts. Hemingway’s friend George Brown served as Plimpton’s trainer, and Hemingway had even tried to get Plimpton to enlist for preparatory fights. Frustrated that Plimpton had demurred, Hemingway’s rage was couched in the common language between them, the language of sparring, and the reluctant Plimpton’s prior evasions. “See how good you are,” Hemingway said, as he hit Plimpton hard enough to make him cry, tears Plimpton would describe as a result of the condition he called “sympathetic response.” Plimpton wrote that, while crying like this, “Suddenly I knew what to do.”

I dropped my hands and asked Papa a question. “How did you do that…how did you bring your hands up from that position?” turning him into an instructor, asking him in such wonder that he was enormously flattered. A smile appeared through those white whiskers.

To finish his Art of Fiction interview with Hemingway, Plimpton proposed a visit to the Havana suburb of San Francisco de Paula, where Hemingway then lived much of the time. Hemingway wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in his house there, which he called “Finca Vigia”; with his famous fishing boat, Pilar, he had used the place as a base of operations to hunt for German subs during World War II. (No subs were found, but the ploy increased Hemingway’s gasoline rations.) To earn this coveted visit—Plimpton had been previously rebuffed—he used Hemingway’s favorite pastime, besides boxing, as a lure. Hemingway took seriously the macho quietude of fishing. He once mocked a friend with an invitation to come bonefishing, “if you want to bring your grandmother along.” In other words there was fishing for women and fishing for men. By inviting himself to fish for the easier prey, as opposed to marlin, Plimpton showed he learned to manage Hemingway’s ego. As effective a self-deprecator in person as on the page, Plimpton steered away from Hemingway’s competitive irritability and positioned himself as a fool before the master’s throne. “If you want a talisman I’d have to admit I’m not the best to have around. Last time out on the Gulf Stream I had the smallest sailfish on the line ever seen in those parts.”

Since childhood, Plimpton always had what his Paris Review co-founder Peter Matthiessen once described as a “social genius.” He signaled to Hemingway that he was no threat, that he needed the older writer’s advice, his wisdom, and that in Plimpton he had a devoted disciple and friend. It worked. When finally Plimpton visited Hemingway, in late winter 1959, the interview had already been published—finished by correspondence. The house’s famous ceiba tree would have been in bloom, and the day of fishing they shared had been sunny and fun.

Plimpton’s interview remains much cited to this day, especially for its iceberg analogy: “I always try to write on the principle of the iceberg,” Hemingway said cryptically. “There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows. Anything you know you can eliminate and it only strengthens your iceberg. It is the part that doesn’t show. If a writer omits something because he does not know it then there is a hole in the story.”

More than a year before it was published, the interview was sought for syndication by at least four CIA magazines. The CIA had worried in the years after World War II that the Soviets’ fame in funding culture might turn out to be a lure to Western European intellectuals as their highly rationed, bombed-out region repaired itself. Melvin Lasky, an officer of the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom and an editor of its first magazine, Der Monat, in Germany, wrote on Paris Review letterhead, its logo and address crossed out, to thank the magazine’s Paris editor for showing him a draft of the Hemingway interview. Lasky asked to see the interview again when it was closer to done, but it was close enough for him to know he wanted it. For Der Monat, he wrote, “I should very much like to have first crack at the German rights…

But could you start the correspondence [for] an option on the Spanish, Italian, and possibly French translation rights. Our associated reviews in those languages might very well be interested too. In which case with a good lump sum most of the foreign rights would be disposed of.

The magazines the CCF sponsored in those languages were, respectively, Cuadernos, Tempo Presente, and Preuves, and all were overseen, launched, and funded by the Central Intelligence Agency. The Hemingway interview touched only lightly on politics, specifically in discussing the Ezra Pound affair. But as far as CCF magazines were concerned, the literary value of American and “pro-Western” authors was now a standard commodity used for positive cultural diplomacy. The five-year-old Paris Review was enabling a clutch of CCF magazines to offer a new snapshot of a popular American novelist who had won the 1954 Nobel Prize for Literature, and whose work had shown sensitivity to Cuban poverty and, in its way, the plight of developing nations.

But for the magazine’s editors, cultural diplomacy was surely secondary to promoting The Paris Review. And for that, Hemingway’s appeal was far-reaching. Plimpton’s Paris editor, Nelson Aldrich, wrote to the New York office, “Laski [sic] is coming to Paris any day now and I will give him the H. interview as per instructions.” He continued, “I have already heard expressions of interest from magazines in the countries of our Axis allies…. In short, I guess we shan’t have much trouble selling Papa.” The Congress’s magazine in Japan was called Jiyu, or “Freedom.”

Did Plimpton realize that he was making the defiantly leftist Hemingway into a US propaganda tool, even vaguely? Aldrich, for one, believed that Plimpton knew the CCF was a CIA front. The magazine wasn’t just engaged in the relatively harmless practice of syndicating Western authors for positive propaganda. The Paris Review had envisioned a symposium around the Pasternak controversy of late 1958, when the Soviets banned the publication in Russia of the original Russian text of his novel Doctor Zhivago. The CIA schemed to smuggle an edition into Russia, via the World’s Fair in Brussels, while Plimpton jumped at the chance to juice the controversy, writing to his colleagues that the Congress for Cultural Freedom might fund brochures and create a publicity campaign around it. When they first discussed it, The Paris Review’s editors, one of them transitioning to a position at the Congress for Cultural Freedom proper, may not have known how much danger Pasternak was in. Foreign visitors represented enough of a threat that the Soviets had Pasternak place a sign in English in front of his house that read: “no foreign visitors allowed.”

But did Hemingway know? Though many of the letters between Plimpton and Hemingway are archived, suggesting a near-complete collection of their editorial correspondence, there is no hint in them that Plimpton ever told Hemingway that his interview would be reprinted in covert state lit mags. Amid all their friendly back and forth, in which recreational and editorial endeavors merged, Plimpton never dropped a word that the interview they had worked so hard on together, over which Hemingway toiled against his pain—rewriting it again and again despite health concerns and depression, fighting for time against his paying work in order to finish—could appear in the European and Asian magazines of the CCF. Was this because Plimpton assumed that Hemingway would demur?

Plimpton also tried to steer Hemingway’s leftward politics back to the vital center. In October 1959, months after visiting Hemingway in Cuba, Plimpton sent a note that was off tone. “I hope to catch a glimpse of you on the way through [New York]. It’s been a summer and fall of slow death, realizing what I missed; I just couldn’t get away, try as I did.

But there were good moments in the summer here. I wrote well. I did a few more stunts for the [participatory journalism] series…but you’ll find me very much the listener come your arrival. I’m afraid it may have been worth shucking all responsibilities to see just a portion of what you saw this summer. I will always remember your initiation to it, and a steady smoldering rage at being unable to do anything about it.

Among Plimpton’s solicitous, jocular letters, this last sentence above stands out. It points to his disapproval of the tribunals of Batista’s functionaries in Cuba, which Plimpton witnessed on that same trip when Hemingway punched him. According to two former Paris Review editors, Hemingway had taken Plimpton to watch those trials and executions, part of what the Cubans called Operation Truth. Plimpton could little have known how his own government had inspired those tribunals.

Operation Truth began soon after Castro’s revolutionaries came to power in Havana, aimed at the hundreds of functionaries of the ousted dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, the US ally who had fled into exile and left a long list of war crimes and criminals in his wake. Hemingway hated Batista, and even recorded that the bastard’s soldiers had killed his beloved dog. Guevara, Castro’s second-most-powerful comrade, after his brother Raúl, would now have his chance to put the lessons from Guatemala into action. The mistake had been allowing members of the old regime to stay, Guevara believed, and allowing those with mixed loyalties to hide in the new government and in the armed forces. Guevara had been in Guatemala City during the US coup there, and he had even tried to rally militias from the supporters of the democratically elected president, Jacobo Árbenz. His first attempt at armed revolution, then, was defensive, and it arose against a hated American coup that led to tens or hundreds of thousands of dead Guatemalans.

Knowing the Americans might attack Operation Truth in the media, the newly ascendant Castro had put out a call for writers to visit, simply to observe and listen at the tribunals. Younger writers, journalists, leftists, revolutionary idealists, anti-imperialist Latin Americans, and at least one future Nobel Prize winner—Gabriel García Márquez, then a budding journalist—were among those who attended. Though the American media was loud and unanimous in its condemnation of what it saw as arbitrary executions in Cuba, historians described the tribunals instead as a provisional justice to appease the people. “To demonstrate that these were war criminals and not simply followers of the ousted dictator,” scholars Ángel Esteban and Stéphanie Panichelli wrote, Cuba opened the trials to the world.

In his published version of events, Plimpton was more lighthearted than he had been in his letter to Hemingway, and the “smoldering rage” belonged instead to theater critic Kenneth Tynan, also in Cuba for the trials. In Shadow Box, Plimpton’s 1977 book about Mohammed Ali, boxing, and the New Left, he tucked in a vignette about those executions that lasts a few pages: “That very evening there was going to be a lot of activity in the fortress,” he wrote. The writers were drinking with an “American soldier of fortune” who went by the name Captain Marks, and who would “be delighted if we would consider joining him as his guests at what he referred to as ‘the festivities.’… At this point there was a sudden eruption from Tynan. He had been sitting, rocking back and forth in his chair; he came out of it almost as if propelled.”

Unable to resist playing with Tynan’s stutter, Plimpton continued in a send-up of the serious political convulsions that Cuba was experiencing:

At first, I don’t think Captain Marks was aware that these curious honked explosions of indignation from this gaunt arm-flapping man in a seersucker suit were directed at him, but then Tynan got his voice under control, and Captain Marks could see his opened eyes now, pale and furious, staring at him and the words became discernible—shouts that it was sickening to stay in the room with such a frightful specimen as an executioner of men (“l-l-l-loath-some!”), and as for the invitation, yes he was going to turn up all right, but in order to throw himself in front of the guns of the firing squad! He was going to stop the “festivities”—the word sprayed from him in rage—and with this he pulled his wife up out of her chair…and rushed to the exit.

When Tynan’s wife and biographer, Kathleen Tynan, recapped the scene, it was clear that Plimpton was himself compelled to watch the executions. The allure of something so politically “loathsome” attracted him. Didn’t the participatory style call for it? “Plimpton, to his own shame, wanted to attend that execution,” she wrote, “and he went over to Hemingway’s finca that afternoon to get some advice and tell him about Ken, how Ken had stunned the man Marks and steamed with rage.

Hemingway felt that it had been a mistake to ask Ken to an execution since his emotional makeup was just not suited to such things, that he would give the revolution a bad name. But he encouraged Plimpton to go.

Tynan continued, “Thus armed, Plimpton set off to meet [Tennessee] Williams for the event. Tennessee had discovered from Captain Marks that a German mercenary was scheduled to be shot that evening and he felt that if he had the chance to do so he would get close enough to give him a small encouraging smile.”

In the end, the execution was canceled. “Frankly, I have no idea whether Tynan was actually responsible,” wrote Plimpton.

I like to think that he was; that the officials got wind of his outraged reaction to Captain Marks…that he was going to throw himself in front of the guns. No, it was best to let things cool down; to let this weird fanatic clear off the island.… At least they would not have to worry that just as everything was going along smoothly, the blindfolds nicely in place, not too tight, just right, Tynan’s roar of rage would peal out of the darkness (“St-st-stop this in-in-infamous be-be-behaviour!”), and he would flap out at them across the courtyard, puffs of dirt issuing from his footfalls as he came at them like a berserk crane.

Plimpton’s account, first appearing in print almost two decades after the event, makes light of the varied responses, each of his friends’ reactions standing almost satirically for different sensibilities of the political and cultural left. If not for Williams, Plimpton himself might have come off in the various accounts as the politically frivolous one. Between Tynan’s righteous indignation and Williams’s blasé flirtation, Plimpton positions himself (with an assist from Tynan’s wife) as occupying a reasonable middle space—the literary equivalent of the vital center—from which he can make jokes and pass others’ judgments.

Yet this story also had a way of changing with the times. As late as 2009, The Paris Review’s former managing editor, James Scott Linville, reversed his colleague’s position in a piece for Standpoint magazine, showing Plimpton heroically drawing a line in the sand against injustice, like Tynan but without the silly stutter, while Hemingway drank and enjoyed the sunset executions.

Linville recalled receiving, in the mid-1990s, Guevara’s Motorcycle Diaries in galleys. He asked to excerpt it in The Paris Review. The Cold War was over. The Diaries were more humanist than Marxist, he believed. So Linville was surprised when Plimpton, feet up on his desk, refused to publish an excerpt from that book or anything by Guevara. “It was right after the revolution,” Plimpton told him, explaining his stance. Hemingway took him on an expedition.

The nature of the expedition was a mystery; Hemingway made a shaker of drinks…. They got in the car…and drove…out of town. They got out, set up chairs…as if…to watch the sunset. Soon, a truck arrived. This, explained George, was what they’d been waiting for. It came, as Hemingway knew, the same time each day. It stopped and some men with guns got out…. In the back were a couple of dozen others who were tied up. Prisoners.

The men with guns hustled the others out of the back of the truck, and lined them up. Then they shot them. They put the bodies back into the truck. I said to George something to the effect of “Oh my God.”

Linville proceeded to describe the executed men as “political prisoners,” and compared these executions to those in Chile following the 1973 coup. “About Guevara’s role in [their] execution,” he crescendoed, “the world has taken less interest. For myself, after reading the accounts I was never able to feel the same way about some things ever again.” It’s beautifully euphemistic. Here the famed editor of the “apolitical” Paris Review, condemning the revolution without acknowledging the US role in its development, was fronting Linville’s very political reading of history.

It was that same political reading of events that, in 1961, had lead the US to one of its most famous military and public-relations disasters: the failed invasion attempt at the Bay of Pigs. And weeks before that invasion, Plimpton would do a bit of subtle lobbying in order to leverage Hemingway’s politics. While it’s difficult to pin down Hemingway’s precise views on Cuba in the period of the late 1950s and early 1960s, just before he died, Plimpton would have known that he was somewhere between favorable to the Cuban Revolution and wary over how it would mature once in power. Hemingway had donated money to the Cuban Communist Party and famously went fishing with Castro and Guevara at the onset of their incumbency (in a fishing tournament that Castro won, and Hemingway judged). Clancy Sigal has written, “When the Batista regime fell, Hemingway wished Fidel ‘all luck,’ and later donated his Nobel Prize to Castro. Henceforth the new revolutionary government honored ‘Ernesto’ as an adopted son of Cuba.”

With Castro in power, Hemingway weighed in on the storm over Operation Truth by denouncing the US media for their Cuba-bashers, and he even kissed the Cuban flag. “I consider myself one more Cuban,” he said. “My sympathies are with the Cuban Revolution and all our difficulties. I don’t want to be considered a Yanqui.” This all went dutifully into his secret FBI file. The scholar Keneth Kinnamon recounts how Hemingway’s doctor, Dr. José Luis Herrera Sotolongo, linked Hemingway to Fidel Castro. Hemingway had backed the overthrow of the dictator Gerardo Machado in the 1930s and had supported the Cuban Communist Party with donations amounting to twenty thousand dollars through the Cuban Revolutionary period.

Hemingway left Cuba in 1960, after the US ambassador to Cuba had told him that his continued habitation in the country was regarded as unpatriotic by the United States. Valerie Hemingway, the writer’s daughter-in-law, wrote that “Papa” bristled at the suggestion “fiercely.” In early 1961, Plimpton sent the novelist a friend’s open letter to Fidel Castro, asking the Cuban leader to reconsider allying his country with the corrupt Soviets. The open letter made the case for reform in Cuba, arguing that nonalignment was better than Soviet alignment: an ideological and a moral plea. (Practically, however, Hemingway knew that the Cubans would need to sell their sugar crop to somebody, and the United States wasn’t buying. It wasn’t just Fidel who chose the Soviets; it was the United States that forced Fidel’s hand.)

Sent as an enclosure, a mere FYI between friends, the letter was certainly harmless, and Plimpton was no doubt right that it would interest Hemingway. Yet Hemingway read it while he still entertained hopes of returning to Cuba. He was depressed as hell; in the US he was being followed by spooks, though no one believed him on this point. Then came the Bay of Pigs—open hostility against his adopted country by his beloved home country.

Hemingway shot himself in his Ketchum, Idaho, home in July 1961, three months after the Bay of Pigs and a year after he had been bullied into leaving the island he so loved because his presence there had grown contentious. His FBI file, released many years later, confirmed that, indeed, he was followed and watched as relentlessly as he had said. At Mayo Clinic—where he had received shock treatment to align his delusions with the world that denied them—one of the psychiatrists even “contacted the FBI to ask permission to tell his patient, who ‘was concerned about an FBI investigation,’ that ‘the FBI is not concerned with his registering [at the clinic] under an assumed name.’”

Whether the FBI ever worried that the constant surveillance might have had a calamitous effect on Hemingway’s mental health is not clear. Hemingway biographer and friend A.E. Hotchner wrote an op-ed fifty years after the novelist’s suicide, admitting that he had minimized Hemingway’s paranoia. “In the years since, I have tried to reconcile Ernest’s fear of the FBI, which I regretfully misjudged, with the reality of the FBI file. I now believe he truly sensed the surveillance, and that it substantially contributed to his anguish and his suicide.” But it wasn’t just Hemingway’s choice of residence that had been politicized. Though few would have mourned his death as fervently as Plimpton, Hemingway’s literary voice was subtly remade into more Cold War propaganda by the CIA’s magazines, and it had been funneled out to the lot of them via The Paris Review.