By Geoff Watkinson

Our mental health funding allocation has been moving in the wrong direction for decades. The US Department of Health and Human Services cites that since 1986 the percentage of mental health and substance abuse expenditures out of all health care expenditures has continued to drop. In 1986 it was 9.7 percent. In 2014, it is estimated at only 5.9 percent. Although this seems like a minor decrease, it adds up to huge cuts: the 2014 budget is $203 billion, which includes both public and private spending.

Public spending (government dollars), however, accounts for only $118 billion: 30 percent covers prescription drugs (up from just 7 percent in 1986) and 22 percent covers hospital treatment (down from 41 percent in 1986). We’ve been moving away from hospitalization and towards pharmaceuticals. The US government spends approximately $26 billion on mental health hospital treatment, or $500 million per state. Much of this supports current facilities, not the construction of new ones. This simply isn’t enough.

We’re overmedicating and undertreating. One in five Americans is on psychiatric medication. Yet less than one-third of people on antidepressants have actually seen a therapist. Much of this has to do with the sparseness of mental health care professionals rather than patient aversion to seeing them, as well as the cost associated with such visits.

By the 1990s, the country simply no longer had the infrastructure to house and care for the mentally ill. Doctors started writing scripts instead

The good news is that because of the new health laws, cost may become less of a burden. Florida, for example, has implemented a Medicaid-based program designed for people with Serious Mental Illness (SMI). The program has an estimated value of $1.5 billion over the next five years, and because of its comprehensive coverage for those with SMI, the state believes it will actually save money on overall costs. Approximately “140,000 low-income Floridians are expected to be eligible,” providing a group of people with coverage who have, historically, had a difficult time receiving it. The goal is to get Floridians enrolled, and provide patients with the treatment they need—doctors, specialists, and other staff—before hospitalization becomes the only option.

But until this transition happens nationwide, and a generation has seen its benefits, we still have a well-documented shortage of mental health facilities. In 1959, the total US population was just over 177 million, half a million of which were institutionalized. By the late 1990s, the general population had grown to over 270 million, and yet only 70,000 people were in mental hospitals. The deinstitutionalization process of the 1970s was greatly responsible for this shift, but new infrastructure was never built. Sure, medications improved over the course of those decades, increasing recovery and granting some people with SMI the ability to function within the community. But by the 1990s, the country simply no longer had the infrastructure to house and care for the mentally ill. Doctors started writing scripts instead.

The President’s new initiative has granted approximately half of the total cost of building a 320-bed facility.

The story of Virginia Senator Creigh Deeds—stabbed by his mentally ill son who couldn’t get admitted to a mental health facility because of a bed shortage—is representative of the fact that many of those with mental illness who seek inpatient care are turned away (see the January 2014 60 Minutes feature). Unfortunately, it has taken the combination of a high-powered political figure and a barrage of mass shootings to put the spotlight on mental illness. Still, the federal government is doing little about the problem.

President Obama launched the “Now is the Time” initiative in January 2013 in response to the Newtown Elementary School shooting. It was a four-part plan “to protect our children and our communities by reducing gun violence.” The plan included closing background check loopholes, banning assault weapons and high capacity magazines, making schools safer, and, lastly, “increasing access to mental health services.” But it allocated a mere $164 million “to expand mental health treatment and prevention services across the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).” Let me put this number in perspective. In 2013, Massachusetts opened a new 320-bed psychiatric facility. The cost was $302 million. So the President’s new initiative has granted approximately half of the total cost of building a 320-bed facility.

Gun violence and mental health care are huge issues on their own. Congress can’t even pass a roads bill. They’re not going to pass some sweeping piece of legislation that tackles the major obstacles of both gun violence and mental health. But maybe—just maybe—they can tackle mental health care. It’s a bipartisan issue, and arguably the most pressing domestic policy decision of present time.

Congress cannot ignore the fact that prisons have become the new mental health facilities. In a 2006 Special Report (a new report is in-progress), the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) “estimated that 705,600 mentally ill adults were incarcerated in State prisons, 78,800 in Federal prisons and 479,900 in local jails.” That’s 1,264,300 incarcerated mentally ill people in a single year. According to the BJS, there were a total of 6,937,600 people in the correctional system at the end of 2012. Thus, at least 18 percent of all those incarcerated are mentally ill (although many estimates put the number much higher).

Individually and collectively, we need to be empathetic. We need to see the brain as it is: the most complex organ on the planet that, like any other organ, gets sick.

The lack of hospital beds also leads to homelessness. PBS reports that approximately 39 percent of homeless people are mentally ill, and 20 to 25 percent of these people meet the criteria for Serious Mental Illness. The specific number of homeless people in this country varies dramatically, but according to the 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, on a single night in January 2013, there were 610,042 homeless people. In other words, that 39 percent means that approximately a quarter of a million homeless people are mentally ill.

We’re never going to get these numbers down to zero, but these numbers are shameful.

The federal government, in conjunction with the states, needs to come up with a 10-year-plan for fixing mental health infrastructure. The new health care laws will help force some of this effort but substantially more needs to be done.

We need to create comprehensive programs that aim at providing services to individuals before they’re at the stairs of a hospital or prison, similar to what some states like Florida are doing. And if someone does need to go to a hospital, then there needs to be a bed for him or her. We need to build dozens of these new state of the art facilities—the antithesis of the facilities that closed in the 70s—like the one recently opened in Massachusetts, where people can have access to inpatient treatment when they need it. We need to incentivize degrees in psychiatry, psychology, and counseling to build a new generation of mental health workers. This is an industry that can create tens of thousands of well-paying jobs. And doctors need to not simply write a script for someone feeling depressed; they need to refer patients to counselors who can in turn offer the emotional support that no pill can.

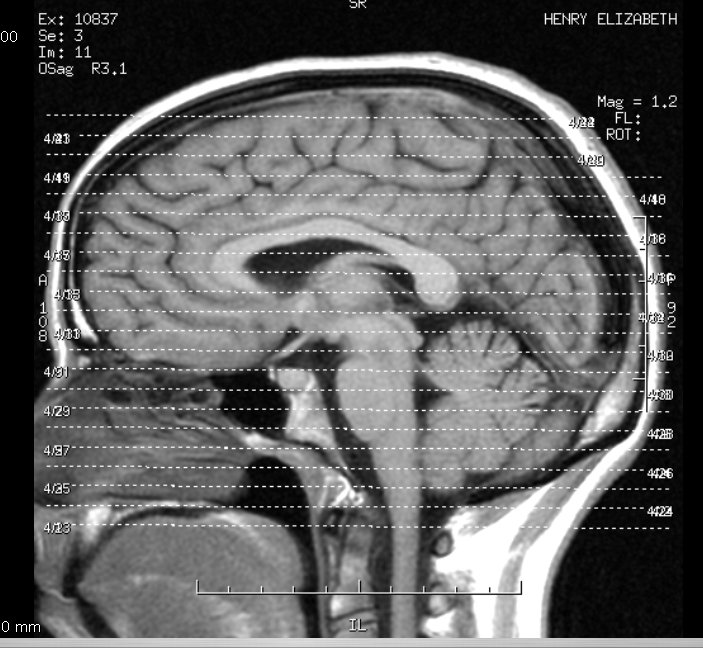

Individually and collectively, we need to be empathetic. We need to see the brain as it is: the most complex organ on the planet that, like any other organ, gets sick. We need to recognize that most people who get sick also get better. We need to eliminate the stigma of mental illness. And the best way to do this is to be advocates for the most basic of care.

Geoff Watkinson founded Green Briar Review in June 2012. He has an MFA from Old Dominion University, where he was the managing editor of Barely South Review. Geoff has contributed to Moon City Review, The Good Men Project, Bluestem, Prick of the Spindle, and FLARE: The Flagler Review, among others. He’s received residencies/scholarships from the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center and Wildacres. Find him at www.geoffwatkinson.com.