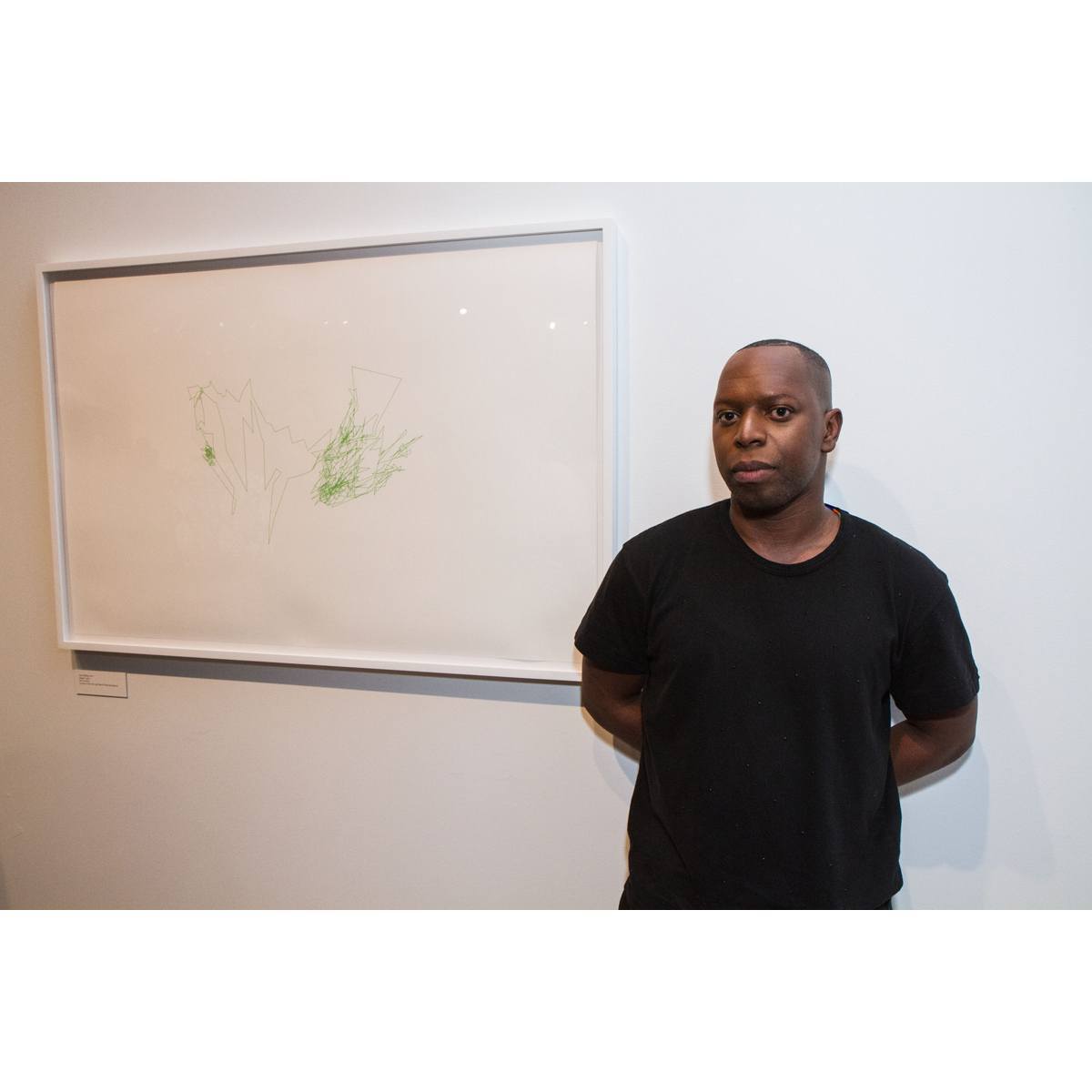

Installation view, New Orleans Museum of Art, The Great Hall, 1st Floor (Photo by Mike Smith)

June 21 - Sept 15, 2013. Photos by Mike Smith, and "FIVE" (Drawing Center) in New York, performed live March 6, 2014. Photos by Jena Cumbo, courtesy the artist

E

arlier this month at the Drawing Center, Rashaad Newsome presented the latest production of “FIVE,” a multidisciplinary performance piece that he debuted in 2010 as part of the Whitney Biennial. This time, the piece incorporated an Xbox Kinect camera, which was used as a pen to reproduce the gestures of his performers three-dimensionally. As before, in three previous presentations of the piece, Newsome conducted the work from a laptop using a color-coded system he conceptualized with Max/MSP and Jitter software.

“FIVE” perhaps best exemplifies the Baroque tendency in Newsome’s practice, because it uses the body as a platform to explore the dynamic visual spaces of vogue, sculpture, and vector graphics. While much of Newsome’s work is a synthesis of historical iconography in art, “FIVE” specifically recalls action painting. The lines generated in real time during the performance capture the improvisational responses of each dancer to live music and to commentary by Kevin Jz Prodigy. A forthcoming series of in-the-round sculptures will be based on the resultant 3-D drawings and the five primary elements of vogue-femme choreography.

A fellow Louisianan, I have followed Newsome’s work since 2008, when we first met in New York. I relate to the feminist impulse in his work, and the drive to dismantle hierarchy through performative acts and gestures. Empowerment is a recurring theme of Newsome’s artistic practice. Strong female characters are among his common subjects, and their privilege is often equated with decorative excess.

The narrative in Newsome’s work explores heraldic systems of achievement and rank derived from New Orleans’s rich history of pageantry and parades. This past summer, the New Orleans Museum of Art featured more than a dozen of his custom-framed collages in the exhibition King of Arms. I organized that project with him as well as a separate presentation of his Swag: The Mixtape video-portraits, which ran September through January in Baton Rouge.

An insider of two cultural establishments—hip-hop and the art world—Newsome builds a creative space that manages to critique both worlds simultaneously. His work is also heavily influenced by New York’s 1950s and 1960s performance scene and the collaborations that occurred between artists like John Cage and Merce Cunningham. He produces a picture of the American vernacular that refuses to be easily categorized as either visual art or pop culture.

Newsome and I sat down in the studio in late December to discuss the projects he has worked on over the past year. Our conversation touched on exhibitions, stereotypes, carnival culture, and his “Jungle Gardenia Tincture” for the Lamborghini Murciélago.

—Laura Blereau for Guernica

Guernica: The kind of art that you create has found a wide international audience, yet its themes are emblematic of the Gulf Coast. How did being raised in New Orleans influence your perspective on art and culture at large?

Rashaad Newsome: When I think about New Orleans as a point of inspiration, I think about growing up in a place where street theater is so readily available all the time. Brass bands are vibrant. Drumming, improvisation. In my work I often use improvisation as a device to compose. For example, it’s a very important component of my performances “FIVE” and “Shade Compositions.” In that sense, I think part of my process is connected to the musical traditions of the New Orleans landscape. I’m also influenced by the region’s sense of color, ornament, its interest in pageantry, obviously, and Baroque architecture.

I did not want to leave New York and I feel like I’m such a New Yorker. But I knew that in order to continue to make the work I wanted, I needed to find some kind of loophole, and connecting with the squatting network was it.

The experience of art can be had strolling from Camp Street to the Bywater, and on that walk one can encounter so much. Maybe someone is playing a trumpet, and then you go a little further and see a mime; then up the block somebody is singing, and another person is painting canvases on the street. Whether it is “good” or not is debatable, but there are a lot of artistic gestures constantly happening around you there. It’s a very accessible art community that way.

Guernica: What were you aiming to find when you left Louisiana in 2001? I understand that shortly thereafter you went on to squat in Paris, Berlin, and Zurich.

Rashaad Newsome: At that time I thought New York was the center of the art world, and I wanted to be a part of that. After being in New York for a while, I found myself in Europe. When I went to Europe initially, I was working on “Shade Compositions,” and during my time there I conducted my own ethnographic research on black vernacular. I gained so much information on those trips, not only for the work but also on a more practical and financial level. New York is a really difficult place to live and maintain a studio practice. I was already aware of squatting from my early punk-rock days, so part of the experience in Europe was just finding a space to continue to create comfortably, yet nomadically. I did not want to leave New York and I feel like I’m such a New Yorker. But I knew that in order to continue to make the work I wanted, I needed to find some kind of loophole, and connecting with the squatting network was it.

Guernica: During the Prospect 1.5 biennial in New Orleans, an exhibition at Good Children Gallery featured video documentation of “Shade Compositions” performed at the Kitchen in NYC. “Shade” is a piece with roots in collaboration as well as in culture from the American South. How did it originate?

Rashaad Newsome: My performance of “Shade” at the Kitchen was far more Baroque than its beginnings. The very first effort toward “Shade Compositions” was when I directed my roommate in Brooklyn in 2004 to stand in front of a camera and perform a series of gestures. That led to a conversation about how that gestural language had become a part of popular culture, yet was still very stigmatized.

I was introduced to software which would change “Shade” drastically, especially in terms of how improvisation was handled. It all comes back to jazz, right?

For me, black American women were the starting point for this vernacular, and I am interested in their hyper-performance of femininity, mainly because gestures that are considered to be the stereotypical body language of black females are also the same for gay males globally. You see it so much on reality TV and in pop culture. The way the women are communicating is very akin to the gay community—and the fact is that guys are often behind the scenes on these shows, doing the makeup, hair, styling, etc. Somehow these men are manufacturing the look and communicating through the women.

Eventually I had a studio residency in Paris while I was doing research on European appropriation of this vernacular. During the day I would go to different parts of the city, such as the Marché Barbès, and ask specific women I met to visit me at the studio. Then I asked each participant to stand against a white wall and perform a set of gestures that were already prescribed for the piece. I also asked them each to give me something gestural that they do, or that family members do. Gradually, I started to build this library of appropriated American vernacular that I observed not only in France, but also Germany, London, and Italy.

The first live “Shade Compositions” was at Glassbox Gallery in Paris, and all of the performers in it were from Africa, not Europe or the United States. It was interesting meeting women from continental Africa who were not African-American, but yet were owning the language as well. The whole experience made me consider authorship.

A few years afterward, in New York, I had a residency at Harvestworks and I was introduced to software which would change “Shade” drastically, especially in terms of how improvisation was handled. It all comes back to jazz, right?

Guernica: A few years ago, you collaborated with vocalist A$AP Ferg, from Harlem, who is part of a younger generation of MCs. Can you talk about how that project happened and why you wanted to work with A$AP Mob?

Rashaad Newsome: I first met A$AP Mob through a friend named April who organized the 2011 Bomb magazine party at Marlborough Gallery. When we were introduced I had just finished all the music for Swag: The Mixtape, a video series for my first show there, and I wanted to test it. The event doubled as a listening party for me. What better way was there to test it than to have a bunch of rappers rhyme over it?

Sometimes rappers are stuck in a hyper-masculine world and seem to worry about guilt by association when it comes to collaborating with gay guys. I admire A$AP because they don’t have those kinds of issues with masculinity. As young black guys, you might think they would have that, but they absolutely don’t.

It’s a real sign of the times. Things are different. They’re a lot younger than me, and I think A$AP demonstrates how the hip-hop world is changing a bit. It has a long way to go, but when I saw how open they were, I wanted to keep working with them.

Guernica: Glittering characters and rites of passage are frequent subjects in your work. We see this in your “King of Arms” performance, as well as in the collages and narrative arc of the video trilogy. Do you locate your art within the tradition of Southern ostentatiousness?

Rashaad Newsome: That’s funny. I went to Memphis and saw Elvis’s house once. These systems are definitely something that I’m playing with. My art is a product of that region and there is a certain way of recognizing value or rank. But it’s just material. The language of power is simply a material in my art practice. That may take various forms: flamboyant dress, movement, words, imagery, objects, but these things still remain part of that universal language of power, so what I am doing can’t be read literally.

Guernica: You recently completed a few album cover projects, including one for Saint Heron records, the new R&B label out of New Orleans that was started by Solange Knowles. How did your collaboration with her come about?

Rashaad Newsome: Solange saw my work at the New Orleans Museum of Art for the first time and just got super inspired. She was looking for ways to approach cover art for the new record label, particularly the release of a mixtape. When we talked she suggested that we do a pop-up trunk sale to celebrate the mixtape and launch of her label. I had the perfect plan because I had just debuted the “King of Arms Float,” a Lamborghini Murciélago wrapped in my “Jungle Gardenia Tincture,” a vinyl wrap. Everything came together so seamlessly. We took the car to four spots: the Studio Museum in Harlem, a retail shop in SoHo called Opening Ceremony, Habana Outpost in Brooklyn, and the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, in her old neighborhood. The Lamborghini’s “Jungle Gardenia Tincture” was a natural extension of the album cover and the perfect vehicle for her to sell her record out of.

Guernica: Your “Jungle Gardenia” certainly gets around. It’s a sports car’s exterior, it’s a collage, and a perfume. How do you see the custom car wrap as a system, and how does it relate to the King of Arms exhibition?

Rashaad Newsome: The “King of Arms Float” is a public sculpture. It exists as an object that you can look at and appreciate. Everywhere it goes, it brings a certain type of energy to that event, no matter where it is. And as a spectacular car, it’s just an event unto itself. It can also generate sounds in many different ways, from the engine to the speakers.

I feel like in some black art, there is pressure to celebrate and not critique. For me, all these things are happening at the same time. There is nothing sacred within the creative process.

In the context of the King of Arms film, which was shot at the NOMA, it’s used specifically as a float, playing with the traditions of carnival. It is a chariot that carries the king. At the same time, it’s referencing the pastime urban communities have of ornamenting one’s car. That’s a parade all its own. It happens in other US cities as well, but my experiences of car stunting came from New Orleans. On Easter Sunday in New Orleans people would show off their cars at the Lakefront. They would take so much pride in it. It was like a piece they had been working on for a long time and were finally exhibiting. I really relate to that in a lot of ways. I was also referencing the annual Order of the Garter processions at Windsor Castle, and the Treme neighborhood Mardi Gras Indian processions, and Super Sunday second lines. So all of that was compressed into this completely contemporary mass processional experience.

Guernica: Are more automobile tinctures in your future?

Rashaad Newsome: Yes, this was just the first. The next one is going to be on the Lamborghini Adventador. It’s much more geometric. I’ll play a lot more with prismatic images and diamond cut on it, because the car itself has a very heavy angular design. I like the idea of taking what I do on a flat page and literally applying that to a three-dimensional object. Even though my collage frames tend to be sculptural extensions, they are not experienced in the round. You can walk around the car 360 degrees.

Guernica: Who is the “King of Arms Krewe” and how does that relate to the film you shot with the car in New Orleans?

Rashaad Newsome: The “King of Arms Krewe” came about through the creation of all my performance work. Mentorship is a huge component of my artwork surrounding the vogue phenomenon. This started with the first two videos Untitled and Untitled New Way, which each serve as formal archives for the vogue language and its history. Vogue, as an art form, got co-opted so early in its creation. In the early ’90s its conversation was relegated to performing gender, but not by anybody who was from the community.

“FIVE” was a platform I created to employ these dancers and also to build a series of live performances. On a practical level, a lot of the performers have difficulty finding work because of their sexuality or gender. I’m not a flâneur. I’m deep in this work, and I view the process as a political gesture. No one is mediating my work with people in the community. This is created for us and by us. And through the process of making that work, I get to see some of the ills, limitations, and frustrations in my community. I feel like in some black art, there is pressure to celebrate and not critique. For me, all these things are happening at the same time. There is nothing sacred within the creative process.

Mentorship is part of the DNA in vogueing culture. You have the Mother of the House, and the Father of the House. I’ve kind of become the mother and father of my own house. It started to grow more and more, so I decided to give it a name, the “House of Arms.” And Mardi Gras season earlier in the year was a turning point for this decision because that’s when my NOMA exhibition plans were finalized. I knew there would be the parade in June, and in New Orleans, carnival krewes always host a ball right before the big parade. So I produced the New York “King of Arms” ball in March 2013. At the time that I was developing everything, all these performers that I mentioned had previously walked in the ball. But they’re not necessarily represented in houses, so I said, OK, so this is the “House of Arms,” which also became my Mardi Gras krewe.

Guernica: Are you planning more balls with the “House of Arms”?

Rashaad Newsome: There will be another one on August 23rd. I’ve decided to do one every year from now on. Some of the most innovative people in that scene are the younger dancers. And last year, because it was held in a bar, some couldn’t go. This next one will be at Riverside Park South, along the West Side at sunset, on a pier that comes out like a really long runway. The piers on the West Side are historical sites. Back in the day, people would cruise on the pier, and that’s where the kids in the houses got together to hang out and practice vogue. So that area is very related to the fellowship and history of the ballroom scene.

Guernica: The NOMA named your krewe “an official parading branch of the museum.” How did the mayor respond?

Rashaad Newsome: The New Orleans mayor, Mitch Landrieu, declared June 21st the “King’s Day for Art in the Park” on opening weekend. The museum is located in City Park.

Guernica: In the museum’s French collection galleries, your “Herald” video hung beside a life-size portrait of Marie Antoinette. Its booming bass line activated the room in an unexpected way.

Rashaad Newsome: Right, the mood was dark—although “Herald” itself is upbeat and essentially presents a coronation ceremony. I think the Gregorian chant and cognac diamond-colored background gave everything a heavy tone in that room, including the paintings of King Louis XIV and XVI. My work does acknowledge darkness, though. Some pieces can be read as really beautiful, fun, and colorful at first, but there is something scary in them as well.

My goal is to walk a tightrope between identity politics and abstraction.

Guernica: In “Herald” is that a moment of death, when your character erupts into flames at the end of the video sequence?

Rashaad Newsome: Yes, you could say death, or perhaps transcendence. For me all those pieces in the trilogy—“Pursuivant,” “Herald,” and “King of Arms”—contain visual cues that represent transformation. It’s not so much about ending an era; it’s more related to my use of transgender people in the work. I’m playing with gender and roles that are shifting as this elaborate allegory for transformation. The body can change. That’s ultimate emancipation, to just completely change your body, to change your physicality. My figures are totems. Incorporating transgenderism into the work becomes this visual cue of what I always want the work to do. I want the work to constantly evolve and change.

Guernica: In doing this, the work mixes such a wide range of influences that it’s not about identity at all. Is it beyond the perspective of one person in a singular instant?

Rashaad Newsome: My goal is to walk a tightrope between identity politics and abstraction. The work plays with identity because of the use of the figure, but everything comes together so abstractly that it’s not really about identity in the end.

Guernica: What is the biggest misconception that people have about your work?

Rashaad Newsome: Sometimes people will see the work and try to anchor it just within hip-hop culture. A lot of the imagery I am using doesn’t even come from music magazines, but from auction catalogs or “high society” ladies. Everything I am working with is very global—the jewelry might come from princesses in the Middle East, or Elizabeth Taylor, or British royalty.

I’m throwing those materials in a blender with architecture and hip-hop royalty to create works of abstraction that speak to fantasy, human impulse, and America’s capitalistic sensibility. My hopes are that the works will encourage a conversation about the complexities of popular culture and the emerging global mainstream.