“Reception” is the first segment in a three-part series. Click here to read part 2, “Presence,” and part 3, “Withdrawal.”

ref·uge

noun

the state of being safe or sheltered from pursuit, danger, or difficulty

1. Protection or shelter, as from danger or hardship.

2. A place providing protection or shelter.

3. A source of help, relief, or comfort in times of trouble.

Wednesday 23 February 2011:

An Afghan man who was denied asylum in the Netherlands has been murdered in the Afghan capital of Kabul, reports Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf. A women’s rights activist and outspoken critic of the Taliban, Nezam Azimi was deported to Afghanistan in 2006 after a five-year struggle to remain in the Netherlands. His death occurred in September of last year following abduction at the hands of Taliban fighters, but the news of his murder has only just now been made public.

According to a recent statement by his daughter, Azimi had been living in hiding since returning to Afghanistan. He was 60 years old at the time of his murder. I am not someone who gets mad. But I felt persecuted. Like they thought I was a terrorist or a criminal.

Thursday 07 April 2011:

An Iranian asylum seeker who set fire to himself in Amsterdam’s Dam Square died of his injuries today in a Dutch hospital. Eyewitnesses observed the man yesterday shouting in broken Dutch before dousing himself in liquid and setting himself on fire near the National Monument to the victims of World War II. A number of individuals in the busy tourist zone attempted unsuccessfully to extinguish the flames.

The 36-year-old man had been living in the Netherlands and seeking asylum for several years. He was denied refugee status for the second time last week after courts turned down his most recent appeal against the rejection decision of the Dutch Immigration and Naturalization Service (IND). According to broadcast news service NOS, Dutch officials are attempting to contact the man’s relatives in Iran.

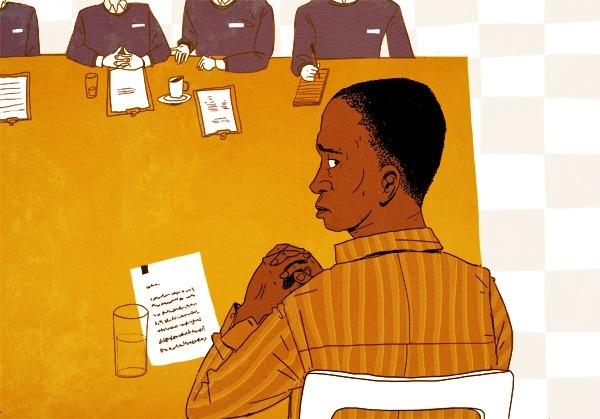

Interview of Adam Al-Ibrahim, rejected asylum seeker, at the Organization for Human Rights and Refugee Health, Utrecht, The Netherlands, December 2012:

DR. MERTENS: I’ll start by asking you about your current living situation. I understand that you have shelter.

ADAM: Yes. I live with two other refugees in an apartment in Amsterdam, in the Indische Buurt.

DR. MERTENS: And you feel this is a safe environment for you?

ADAM: Yes.

DR. MERTENS: Can you tell me about any general health issues you might currently be experiencing?

ADAM: For a long time now I have pain in my back. I have headaches and sometimes I feel that I can’t see anymore out the sides of my eyes. It is difficult for me to sleep at night.

DR. MERTENS: When you first arrived in the Netherlands, did you talk about these problems during your interview with the IND?

ADAM: When I came here I had pain but it was still new. In my interviews I didn’t say anything.

DR. MERTENS: Do you remember an interview with a doctor? Someone like me who asked you about your health?

ADAM: Yes, I remember. But there were too many interviews, too many men. In the room were always five to ten men and I had to talk for hours. I would become very nervous. I don’t know these men, I don’t know how things go here. I remember that during my interview with the doctor I became very afraid. The IND is there, the doctor is there, and I just became too afraid. My lawyer, even the security guard at the interview, they said, “You must stop the interview, this man is not okay.” The doctor from the IND, even he says, “No more interviews, this man is not okay.” But the IND, they still want to interview me. It was then that I felt they are playing with me. They are playing.

DR. MERTENS: Were you angry?

ADAM: Not angry. I am not someone who gets mad. But I felt persecuted. Like they thought I was a terrorist or a criminal. They treated me that way. The IND, they try to trick you. They ask me about dates, to describe a certain situation. Later they ask me the same question in another way. I don’t like repeating things, like I am a program or a machine. They want me to mess up. I don’t trust them.

DR. MERTENS: What were you afraid of during the interview?

ADAM: Everything.

DR. MERTENS: Can you be more specific?

ADAM: In this time I was afraid of everything. I was afraid that Sudanese agents would come to take me. In these interviews I did not know who was from the IND. There are many informers in Sudan, you never know them, you never know who they are.

DR. MERTENS: You were afraid you would be sent back?

ADAM: Yes. From the first day I understood that some people were sent back.

DR. MERTENS: Do you still have fear of being sent back?

ADAM: Every day. Ever since I fled the IND, you know, I have feared the police. If I see police, I shake. I shake. The police here look for any mistake. If you don’t have a bike light or if you cross a traffic light, they stop you. If you are black they ask for your ID, and I don’t have ID. So if my bike light doesn’t work, I walk. I change my route every day. Just last night my friend called me, he said, “Don’t go on the bicycle tonight. They are stopping black people.” Another friend told me to always walk next to white people, to walk on the street with them like you’re in a group with them. The police are embarrassed to stop you in front of white people. I am always afraid, you know. I cannot move here, I cannot be free. I’m afraid even to sleep.

DR. MERTENS: Why are you afraid to sleep?

ADAM: I am always thinking, you know. I see images in my head. War, blood. Other things. Even when I sleep I see these things.

DR. MERTENS: What do you see?

ADAM: (No response)

DR. MERTENS: Adam?

ADAM: I have dreams.

DR. MERTENS: What kind of dreams?

ADAM: Horrible dreams.

DR. MERTENS: Can you tell me more?

ADAM: I wake up in the middle of the night and I can’t go back to sleep. I dream like this five, maybe six times a week. I dream that I am with my family, that war is around us. I see villages falling, being taken over one by one. In my dreams they are always out there, killing men in the villages. My father comes home and he cannot speak, he cannot hear. My mother, she just cries. She is always crying in my dreams. And I am with my family, just trying to stay calm, but I know they are coming for us. Things like this.

DR. MERTENS: Do you take medication to help you sleep?

ADAM: My doctor, he gives me medicine. With it I can sleep fourteen or fifteen hours. If I wake up from a dream I can just go back to sleep. It helps. But I have side effects, you know. I know people that are handicapped, people made crazy by medicine. I have a friend who tells me the medicine will block my mind, that it is like a drug. But I want to keep it. I don’t want to kill myself. The doctor says it is okay, he says if I want to I can stop taking it. He says not to worry. But I do.

DR. MERTENS: Have you thought of killing yourself, Adam?

ADAM: (No response)

DR. MERTENS: Adam?

ADAM: Yes.

DR. MERTENS: Have you tried?

ADAM: No. But I always think about it.

DR. MERTENS: How would you do it?

ADAM: Jump from a building. That’s easy.

DR. MERTENS: How often do you think like this?

ADAM: Maybe every week. I only think of jumping when I feel pain, when I feel that no one wants to help me.

DR. MERTENS: Why do you feel that no one wants to help you?

ADAM: Respect to you all, but I go to so many of these meetings, I meet so often with people, but I don’t trust anyone. I am here for five years now and no one has helped me. I had four lawyers and they didn’t help, none of them helped me. I’m sorry to say, but I feel that everyone just goes home, they forget. They are all at work. It is a job for them. They just want to be busy with me, to fill their hours.

DR. MERTENS: I understand that must be a difficult feeling for you, Adam. But I must remind you that all I’m here to do is to evaluate your situation. This is not therapy and I’m not in a position to offer you help or advice. All I can do is document what you tell me. Does that make sense to you?

ADAM: I understand. It is their right in the Netherlands to seek asylum, it’s not like a criminal procedure, I’m not an interrogator.

Selected text from the Immigration and Naturalization Service online fact sheet, The Procedure at the Application Center, accessed April 2013:

What happens during the asylum procedure?

1. Initial interview

The initial interview is a meeting with an IND employee. The interview is intended to establish the identity, nationality and travel route of the asylum seeker.

2. Detailed interview

The detailed interview is a meeting with an IND employee during which the asylum seeker will be able to tell why he applied for asylum. An interpreter will be present at this interview as well. A legal assistance counselor will prepare the asylum seeker and is allowed to attend the interview. The asylum seeker will first tell his story after which the IND employee will ask questions.

3. Report and intended decision

After the detailed interview, the IND will decide what should be done with the asylum application. There are three possibilities:

- The asylum seeker satisfies the conditions for an asylum residence permit. The asylum application is granted.

- The IND needs more time for the investigation. The asylum application is handled further in the Extended Asylum procedure. An asylum seeker will receive a report of the detailed interview and will be placed in a reception centre.

- The asylum seeker does not satisfy the conditions for an asylum residence permit. He will receive a report of the detailed interview and a written intention to reject the asylum application. The intention contains the grounds for the rejection. The asylum seeker, together with the legal assistance counselor, will be afforded the opportunity to provide additions and corrections to the report and to respond to the intention.

Jonathan de Vries, asylum case worker with the Netherlands Immigration and Naturalization Service (IND), Schiedamse Vest 146, Stadsdriehoek, Rotterdam, May 2013:

The interview is I think the most difficult part. I’m training myself more and more to be open, to be more aware of my body language. It is their day, so they just need to share their story without feeling ashamed or rejected. It is their right in the Netherlands to seek asylum, it’s not like a criminal procedure, I’m not an interrogator. I am just here to facilitate, to listen and to ask questions. I ask questions just to get a proper understanding of the story, so we know why, so we see the whole picture. And that needs to be clear. It can really be problematic during an interview if your attitude influences how an asylum seeker feels, whether he or she feels really comfortable to share his or her story, so I always try to reflect, to be neutral in my reaction.

It sometimes happens that we start to ask very detailed questions and we continue to ask very detailed questions because the only way for us to assess their case is based on what they tell us. If they have documents it’s easy for us. But the whole process, because people are usually coming almost without any documents, is based on trust. You’re sharing a story and I really need to trust you in a sense.

Often people in the Netherlands, people on the street, illegals, they say, “Yeah, I’m a refugee.” Of course there are exceptions, but my experience so far is that very few people coming to the Netherlands are really entitled to get asylum. They are rejected because they have no proper grounds to be granted refugee status. That’s the problem in the media; the legal definition of refugee is not being followed. And that makes the debate very hard. It’s hard to engage in this debate when we are talking about people without giving them their proper name.

I think the current laws with regard to asylum and refugees, I think they’re pretty good. For me, the problems we really need to address are issues of inequality. Of course all those people who are not really refugees, I do believe they have challenges. They have reasons. When your circumstances are so desperate, even if you don’t fear for your life, you flee. Or yeah, you seek opportunities. I can understand that they are coming to the Netherlands because probably I would have done the same.

But the majority of people coming to the Netherlands, they come because of the enormous disparity of wealth that exists in the world. That is really the underlying problem. I think that’s what we need to be addressing. And often that debate, that is much more profound, eh? And I feel that’s not really being addressed in the media. It’s always like, oh, they are so, yeah, how do you say? Zeilig. Sad people. And yeah, we feel for them. Of course, I feel for them too, but not that they need to be granted asylum. No. We need to look more in-depth, look at the underlying reasons, to tackle those problems.

Wednesday 29 February 2012:

The number of new asylum applications filed in the Netherlands fell for a second straight year in 2011, according to new figures released by the Dutch Central Bureau for Statistics. The 11,590 applications received last year are the fewest recorded since 2007 and represent a 13 percent decrease from the 13,340 requests filed in 2010.

Wednesday 11 July 2012:

The total percentage of asylum applications accepted by the Netherlands is nearly twice that of the average European Union member state, according to the latest figures from EU statistical database Eurostat. The 45 percent approval rate reported by the Dutch last year was exceeded only by the Czech Republic, Finland, and Slovakia.

In a statement to the Dutch national news service ANP, a spokesperson for the country’s Immigration and Naturalization Service claimed that asylum seekers find the Netherlands attractive because “every request is handled with care.” For a while you know I stop drink, I even stop hash. But after a while, I think for what? I still have pain, I’m still dying.

Tariq Saiyed, rejected asylum seeker, Madurastraat 26, Indische Buurt West, Amsterdam, March 2013:

Old people say god decides where you die, how you die. I say no. If my doctor says I die in one month, I will enjoy. Only enjoy. I will only play. Smoke, drink, fuck, be with friends, be with women. In Pakistan if you die on the street, you die. But at least we enjoy life, we travel, use money. Here I don’t know how they use money. They only save, only work. But me, I’m bound here. I’m captured. If I go home they kill me. So I try to enjoy myself. But this atmosphere doesn’t help me.

For a while you know I stop drink, I even stop hash. But after a while, I think for what? Why I stop? For which reason? For who? I don’t have aim. I still have pain, I’m still dying. So why am I stop drinking? Why am I stop smoking? Why am I stop fucking? I like hard drink. I like to smoke. Me I want to relax, to enjoy. So I don’t think now about my life, I think only about the day.

Me I hate sympathy. If you have too much sympathy for me, I feel you are my enemy. I hate the question: How are you? How am I? I cannot explain you. Me I have pain but I don’t say it. Why I say? And for what? You see my face relaxed now. This is make up. It’s a mask. Me if I don’t have pain, I feel worried. I’m changing my mind, you understand? I’m used to pain now, enjoying it. Nice trick, eh?

The names of all individuals and non-governmental organizations have been changed to maintain anonymity.

Portions of “REFUGE” originally appeared in Dutch translation in the August 14, 2013 edition of the magazine De Groene Amsterdammer under the title “Op zoek naar beschutting.”