As we drove south from the border the sun lowered and the landscape grew quiet, shifting with color and deepening shadow. Kirsten, my partner, was worried about gas. We passed by fields and orchards, following the course of the Bambuto River through the long desert valley that separates the pine-studded heights of the Sierra Cibuta and Sierra el Pinito. In a nameless town we exited the highway and drove slowly over speed bumps, looking for gas. Young men with backpacks walked hurriedly through the streets. For several moments we were forced to pull our car aside to make way for a procession of women dressed in black. I looked to Kirsten. Maybe we should stick to the main road, I suggested.

It was dark when we finally arrived in the town of Magdalena de Kino. As we ate our dinner on an empty restaurant patio beneath the illuminated facade of the Templo de Santa María de Magdalena, a sense of relaxation finally began to settle over us. Kirsten and I lived just a few hours north, in Tucson, and were passing through Magdalena on our way to the Sea of Cortez, where we hoped to find temporary escape from the sadness and anger of our daily work along the Arizona border—Kirsten as a journalist and me as a lawman. We wanted to be far from the poisonous discourse that swirled around questions of immigration, far from the echo chamber amplifying the menace of peripheral violence.

Kirsten was familiar with Magdalena from a prior visit, and after dinner she took me to the small mausoleum that housed the remains of the 17th century Jesuit missionary Eusebio Kino. Centuries ago, Father Kino traveled through the deserts of Arizona and Sonora erecting a chain of mission churches to impose faith upon the native peoples of the region. Under the frescoed dome of the mausoleum, we peered into the crypt of one of Kino’s long-destroyed missions and gazed upon his exposed skeleton lying face-up in a crumbling coffin, his skull misshapen and forlorn in the incandescent light.

In those moments it became possible for us to forget the news of bloodshed and human struggle.

The next morning we resumed our journey to the coast, traveling across densely vegetated bajadas and rolling valleys of mesquite and ironwood. In the hot streets of Hermosillo, the state capital, I became lost. Kirsten and I argued with the windows rolled up, moving slowly through a crush of vehicles. Away from the city, the desert seemed ravaged and we stared out at the landscape without speaking. Several miles from the oceanside town of Kino Bay, we stopped the car to walk through a forest of cardón, the most massive cactus on earth, which often grow in excess of 60 feet. Beneath their hulking arms even the giant saguaro were diminished, scorched and crippled and stripped of dignity.

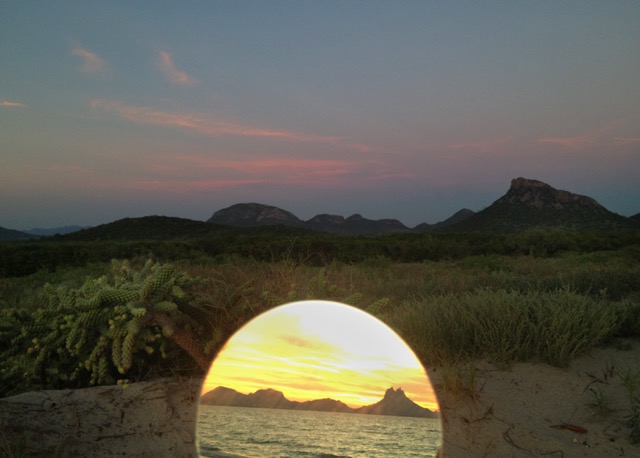

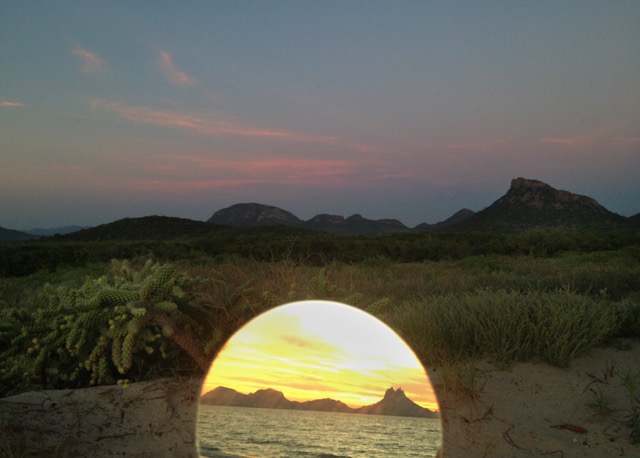

Kirsten and I spent the next two days in the warm glow of the Sea of Cortez. We took pictures of each other squinting in the sun, we combed the beach for the globular remains of cannonball jellyfish, and we flew cheap kites on drafts of salted wind. For long hours we lay on the hot sand, reading and contemplating the islands across the bay, and in those moments it became possible for us to forget the news of bloodshed and human struggle that so relentlessly loomed in our daily perception of the borderlands.

That night, on the balcony of our guesthouse, Kirsten and I drank bad wine and wiped the blood of dead mosquitos from our legs. In the distance a buoy flashed near the uninhabited coast of Isla Tiburón, Mexico’s largest island, a place that once served as a refuge for the indigenous Seri people during centuries of persecution by Spanish and Mexican regimes. Now a depopulated wilderness, the island is rarely visited. As I lay in bed that night, I pictured the surface of the island and imagined animals moving in the dark, crossing a landscape that had forgotten the human violence once visited upon it.

Barely a month after our return to the US, a convoy of black trucks and SUVs would descend upon the town square of Tubutama.

The next morning we left the coast and began our journey home. North of Hermosillo, we exited the highway to travel along the small roads tracing Father Kino’s historic mission trail. We stopped for gas in the town of Altar and decided to pay a visit to its pastel cathedral. We parked among the empty shuttle vans that ringed the central plaza and walked toward the church through empty market stands displaying backpacks, baseball hats, underwear, socks, talcum powder, caffeine uppers, catholic charms, and laminated blessings for migrants on the hard journey north. Shopkeepers seemed to retreat from us behind piles of clothing, hiding their faces under the shade of their tarp awnings. An air of transience and resignation cut through the town and I began to sense suspicion in the sidelong glances of the men lounging in front of the church. As Kirsten and I wandered through the aisles of the cathedral, I looked over my shoulder at a man who appeared to be following us, his phone held out as if to film our every move. The man met my gaze with cold and darting glances. I whispered quietly to Kirsten that we should return to the car.

On the highway north we followed the Altar River through a low-lying valley to the fortified village of Tubutama. On its main square was a whitewashed mission ringed by a small aqueduct and rows of dilapidated adobe buildings. Established by Father Kino in 1691, the building was repeatedly destroyed and rebuilt during successive waves of bloody revolt by the indigenous O’odham population. We encountered no signs of life on our wanderings through the village until, back on the highway, we passed two federal police vehicles, their emergency lights pulsating in the mid-afternoon heat.

Barely a month after our return to the US, a convoy of black trucks and SUVs would descend upon the town square of Tubutama. The town’s few residents estimated the number of vehicles to be anywhere from 30 to 100, all of them painted with white X’s to distinguish them from their rivals. In the early morning hours of Thursday, July 1st, 2010, the convoy headed north toward the Arizona border. As the vehicles negotiated a sharp bend in the highway, members of a rival drug cartel barricaded the road and opened fire from adjacent hilltops. Inhabitants of the nearby town of Sáric were woken from their sleep and reported hearing nearly an hour of sustained gunfire. Officials placed the death toll at 21, but murmurings persisted that more than 100 corpses had been taken from the scene. Photographs made public by the Mexican press showed SUVs and pickup trucks riddled with bullet holes and splattered with blood, a highway littered with dead bodies slumped in car seats and sprawled amid tangled mesquite. In one picture, a man could be seen lying face-up on the roadway, his features twisted and leering in the sunlight, brain matter trailing across the surface of the asphalt.

One evening at our home in Tucson, where Father Kino established what would become his northernmost mission, I shared news of the massacre with Kirsten as we puttered through our brightly lit kitchen. We discussed the events with polite and requisite shock, the way two people might speak of a natural disaster in some far-off and unfamiliar land. Lying in bed that night I thought of the people of Sonora, my neighbors, living under a threat of bloodshed as palpable as it was centuries ago during times of conquest and revolt. As I tried to sleep, I swatted blindly at mosquitos and imagined once again the surface of Isla Tiburón, its mountains and dark waters rippling with moonlight, and I wondered what solace might be found there, in a landscape emptied by violence.