We migrated from Abbottābad to Kashmir before Pakistan was born.

We went from the railway station to the river Jhelum, which we crossed in a canoe. The steady thrum of our movement rippled the valley’s morning silence. Fog momentarily obscured Father, who was separated from me by the length of Mother’s coffin.

Two undertakers, squatting on the bank with their chins propped on shovels, moored us to a tree stump and picked up the coffin. They chanted Quran verses. We followed their lead through a thicket of fir woods and reached the Sunni cemetery. It started to drizzle as they set to work. When the hole was deep enough, they stepped out and whispered to each other.

Father lay down on Mother’s coffin.

I just want to keep it dry, Father said, not getting up, his face beaded with raindrops.

No, one of them said. Don’t you need a holy man?

They fetched a mullah, who fished from the pocket of his long white caftan a clear glass bottle that held sacred Mecca water. A thimbleful from each ancestor who made a pilgrimage, he said. It took six generations to fill the bottle.

I took it, tipped it, thumb pressed to its mouth. The liquid swiveled and met my skin. Cold. Ancient. A water thirsty from a long journey.

Father slid open the coffin lid. I had my first glimpse of her in four days: arms crossed, blue flares of pagoda sleeves brushing her cheeks, which had gone paler.

I ran my glistened thumb down the cleft of her chin.

To the murmur of sacred verses, she was lowered into the hollow. The earth of Kashmir took her. I was sixteen and understood the meaning of forever. The weight of the word—all the time it contained—pressed down on my shoulders.

We moved that afternoon into our new riverside bungalow. Our things were in transit: our old home emptied, boxed, shipped, not delivered, not yet. Father slept on the floor, his face to the wall, as I stood in my room, bare as a limb, and looked out the window. The Jhelum was not the river of my boyhood. It was Father who wanted to bury Mother next to her kin; it was he who wanted to live in her homeland. Our migration to Kashmir was, I knew, his response to the homesick look that stained her eyes in her last days. But my memories of Mother had formed in Abbottābad. During Ramadan, after we broke fast, we went to the night bazaar to eat corncobs hand-turned to a golden brown over crackling embers. In the spring, I sat by her side in the deer park, where she composed sheet notes that she later played on her santoor. When I came back home from summer camp, there lingered on my pillow slip a trace of her cold cream. Posterity turned all that routine to ritual; it enshrined Abbottābad in memory. I resented Father my uprooting and resolved to never call Kashmir home.

On the first white night of that winter, I sat in our library in an embryonic darkness. Our packages had all arrived from Abbottābad, and while every piece of furniture found its corner, every piece of clothing its rack, its hanger, every spice, every vessel a shelf or a hook in the kitchen, we hadn’t yet unpacked our books. The vacant teakwood racks around me smelled of varnish.

There was an explosion of light, and I screwed my eyes shut, and on opening them, I saw Father standing under the flare of a scone light, its string in his fist, a pipe clenched between his teeth, wisps of tobacco smoke billowing about his face. He said, Let’s go out.

This late?

Perfect for tea. You haven’t understood Kashmir until you’ve tasted her tea.

I had no desire to be around the chatter of strangers, to pore over a menu card, to select something under the polite, pressurizing gaze of a waiter, to, with Father’s expectant eyes on me, sip the beverage when it was still a degree too hot: I could feel the scab on my tongue.

I put on my winter coat and went with him. It had stopped snowing but it was still cold. A good winter, Father said. We’ll have a good harvest next year.

You always say that.

I’ve run this business since before you existed, Father did not say. I seethed in his silence as the horses clattered our carriage to the lake, as an old man rowed us across Lotus Lake to the boathouse that served as the tearoom.

Rice lights illuminated the tearoom’s slanting wooden roof. Its windowpanes were squares of flickering amber. On opening the wooden door, the chimes strung to its handle released a bell-like tinkle. Conversations dimmed. Faces looked up from steaming cups.

The cash drawer was shut with a ring. We sat cross-legged in front of a teapoy. The air steamed with the fragrance of cardamom and crushed ginger.

I said, You order, Father. You know the local flavors best.

He beamed. I used to come here with your Mother, boy. Before we got married.

I pictured them: she an orphaned girl of the working class, he a businessman visiting from Abbottābad, the two sitting here, and over a hot mug of tea, their fingers finding each other.

When my tea was served, I dipped in a sugar cube and watched it turn brown. Around me couples leaned toward each other, old men struggled to find warmth in threadbare overcoats, young men in caftans gathered in a circle. Abruptly, the lights were turned out.

In the boathouse opposite the tearoom, a child’s fingers twitched against a hazy gas bulb. A single santoor note and then four more sputtered to life. Someone turned the knob of a lantern, illuminating the face of the musician.

Father had me rowed across a lake flaked with ice slivers this late in the night not for a cup of tea but to tell me that Mother received her musical legacy from the land I rejected.

She played for an hour. Raga Malkauns. On the burning skin of my ears, the santoor notes met: the ones teased by this young stranger, those composed by Mother. A frame stood in our old library: Mother and I, squinting in the sunlight, radiating each other’s happiness.

The audience applauded cheerfully. The lantern was turned down and the bulbs came slowly back to life. Outside, the child’s fingers still twitched hungrily.

This is what we old-timers call music, Father said.

There’s no snow, I said, and pressed my wrists to my eyes.

Father and I spent a week arranging Mother’s books in the library, not alphabetically, but chronologically. Mother marked her date of purchase on every last page.

Taking with me a volume of stories, I went to the cemetery and, leaning against Mother’s tombstone, I began to read.

Reading at her grave became an after-school ritual I took to every afternoon. In September, the hills that circled the woods were carpeted in purple: flowers from whose cores farmers plucked the blazing red herb of saffron. On quiet-skied winter afternoons, I retreated to the wood’s white silence to read, watching, on my way back, old men sitting by windows with lanterns and knitting pashmina sweaters.

Oftentimes, Mother would begin reading to me from a book in her collection, but a narrative image, a story event, a verse would evoke some memory of her girlhood in Kashmir, and the act of reading would turn into an act of recollection—time paused, details teased out, facts repeated. And so once I was in Kashmir, each street, each sound and smell, brought to mind anecdotes, sharpening the bite of her absence.

Her books, on the other hand, by telling stories of Kashmir through a people I shared no history with, by offering personal glimpses in an impersonal manner, allowed me to place myself in the landscape. Thereafter it became safe for me to recollect her anecdotes, to tease more out of Father, to then go to the places where those anecdotes happened, those parks, those streets; I went to the secondhand bookshop still presided over by old Muhammad—silver beard, his cap still spotless as a summer cloud, and indeed, every so often, a sound like that of a hubble-bubble ricocheted up his throat. Picking up a book, I inhaled its aged pages and met Mother from another time and made her acquaintance.

In August 1947, shortly after my seventeenth birthday, as the country celebrated her independence—children running with the national flag in one hand, a pinwheel in the other, farmers offering crops to Hindu deities and Islamic patron saints, womenfolk welcoming independence by leaving turmeric handprints on temple walls—cartographers carved a border through India’s body and engraved on maps the name Pakistan. The distance between Mother’s birthplace and mine remained the same, but they now stood separated by a national border.

Before the year ended, there appeared—on the town’s walls, shop shutters, and dustbins—graffiti that in drooping green ink demanded that India make Kashmir a freed Muslim state. In the riots that followed, kitchen utensils and corpses of strays turned to weapons in hands that couldn’t get hold of things more dangerous. The tearoom was shut down. Canoes that once carried orchids from one side of Lotus Lake to the other stood paralyzed in algae-clogged waters. Hindu farmers fled town, abandoning homes where forefathers were born, where they conducted their boys’ birth ceremonies. They were followed by pandits who chanted hymns of forgiveness before they picked up stone deities from ancestral temples and walked away.

Into such abandoned temples I strayed; I touched stone carvings of decapitated gods and dancers. I walked through a paddy field and arrived at a blackened, balded patch, stepped into empty houses, touched objects left behind: scarves, spectacles, timepieces, shrunken dentures, empty trunks with lids thrown open, rocking horses moving vacantly in the wind.

Our street, which clung to the foothills and housed saffron farm owners, was still safe, each home guarded by patrolmen. It trilled with a quiet so impossible that at dusk we heard the sound of parakeets settling in the apple trees.

With a book of Dinantah Nadim’s poetry in hand, I crossed the river and picked my way toward Mother’s grave. Policemen stood along the fir woods’ border. They wore khaki vests and trousers and helmets in green and held rifles across their chests. I tried entering from between two men. One of them grabbed my shoulder then shoved me back. My book fell behind him and I dropped to my haunches. His face was impassive as he stared straight ahead. I reached for my book. He raised a leg and brought it down, crushing my fingers with a fat leather heel. I howled.

I want my book, Sir, I cried.

Where’s the book? he asked, releasing my hand.

I pointed at it with a swollen finger.

Where’s the book?

Behind you.

Where’s the book?

In the woods.

Which is government property now. So the book is also ours. Zafar! Collect the evidence.

From a jeep to my left, a bearded man in khaki shorts and a half-sleeved brown shirt stepped out with a briefcase. He wore a pair of latex gloves, and with a surgeon’s precision he stuffed the book into a plastic slip, which he sealed. He pasted on top a label on which he wrote the date, location, and the word, Book.

It’s my mother’s book.

And you, mister, had a little meeting planned with a brother from another mother from across the border, am I right? That’s why you were dying to get in. Your fingerprints will tell.

I’m sixteen.

You fellows used six-year-olds as suicide bombers. You’re an old hat by that count.

The patrolman barked, Frisk the boy, Zafar.

I stood spread-eagled. Zafar ran his hands down my body, up again, front then back.

The patrolman said, You checked the crotch properly, Zafar? Dicks, guns, same-same to these fellows.

Sir, please, I said, flinching.

He said, One to shoot, other to raise shooters. You reproduce like rabbits.

He walked up to me. His tobacco breath burned my brow. I shut my eyes.

Six years later, when I flew to New York, the security check—the gloved pair of hands that frisked me—would bring back memories of the policeman’s hands, his fingers poking, curling, squeezing, squeezing hard, until I went from wincing in silence to squealing, giving pain a voice, burning with the shame of giving him what he sought.

Dusting his hands, he said, Now scram before I stuff your skullcapped head with a bullet.

I came home and sat with my hand dipped in a bowl of hot mint-oily water and pondered the weeks before Mother died giving birth to my dead sister. She had lain in bed, her breath shallow and ragged, and I had read to her, my mouth close to her sweating ear.

On opening my eyes, I found Father squatting in front of me.

Mother’s book is government property now, Abba.

Put off doing homework. I’ll write your teacher a letter.

Mother’s grave: that’s government property too?

Do you want to take tomorrow off?

When the cemetery opened again some months later, the borderline, we discovered, ran through it, some graves now in a new country. Survivors had to procure multiple-entry visas and go through border security each time they went to pay homage to their ancestors.

I wish there was good news for me to give, to make you feel better, he said.

What do you mean?

He wants the saffron for himself.

Your manager? What did he say?

Said nothing, not since the partition. That’s one problem.

The other problem being?

My bank account, the one in Abbottābad.

I gathered details in the years to come: men separated from their wealth by the border, they in one country, their wealth in another, petitions to investigate the man in question filed away. Does he use his money against the soil on which he earned it, colluding with our unsavory neighbor? Why else would he be there? The proffered questions were never answered, nor the men ever reunited with their savings.

You’re not going there—I hope not?

Maybe he saw in my eyes the recent headline, the Kashmir-bound express that arrived from Karachi, a train full of dead migrants, just as I saw his eyes flicker, not with the uncertainty of his return if he went, but the fear of what he’d find there.

I better listen to you. You were right last time.

Of course I was.

He laughed, and I joined him, for what else was there to do?

As I drifted into sleep that night, I heard the shuffle of footsteps. They paused outside my door and entered, by my bed. I kept my eyes closed. Father planted a kiss in the air above my forehead. When his footfalls grew faint I watched him walk haltingly down the corridor.

That week all but Father’s rooms, into which I moved, were locked. We let go of all of our staff but our cook who, once a week, for a little extra, cleaned the common areas. No patrolmen guarded our home. Our safety became one of association, flanked as we were by neighbors whose guards kept their nightly vigil—blew their whistles into the dark, ran their batons on iron gates—making our home a lucrative prospect when the rooms were reopened to be rented to people whose houses had been gutted.

Father found a job as a manager on our neighbor’s saffron farm, and every evening as he made polite conversation with our tenants, I knew that his face was flushed not from a long day of work. He strained to give the scent of saffron a new meaning, a new verb.

I paused once outside a rented room where a woman ran a comb through her daughter’s freshly oiled hair. She met my gaze and her face blossomed with a startled look—startled that she was no longer startled by her situation, her home gone, her family’s life confined to a single, rented room. Behind her a strung sari dripped drops of indigo into the balcony’s once-immaculate silence. The strange had become our reality’s material substance.

One morning when I heard Father return earlier than normal from his morning walk, I came down the stairs and found him at the dining table. Next to a steaming teacup there sat a handmade poster conveying an appeal from the library for books.

But they’re Mother’s books, I said, realizing how feeble my words of protest were, realizing the fact of their utterance only in their wake—that therein lay an already-made decision. Together we went up and unlocked the library door. The books looked ready for their freedom. I held him, my shuddering and the ragged sounds I produced a camouflage in which he too could let go.

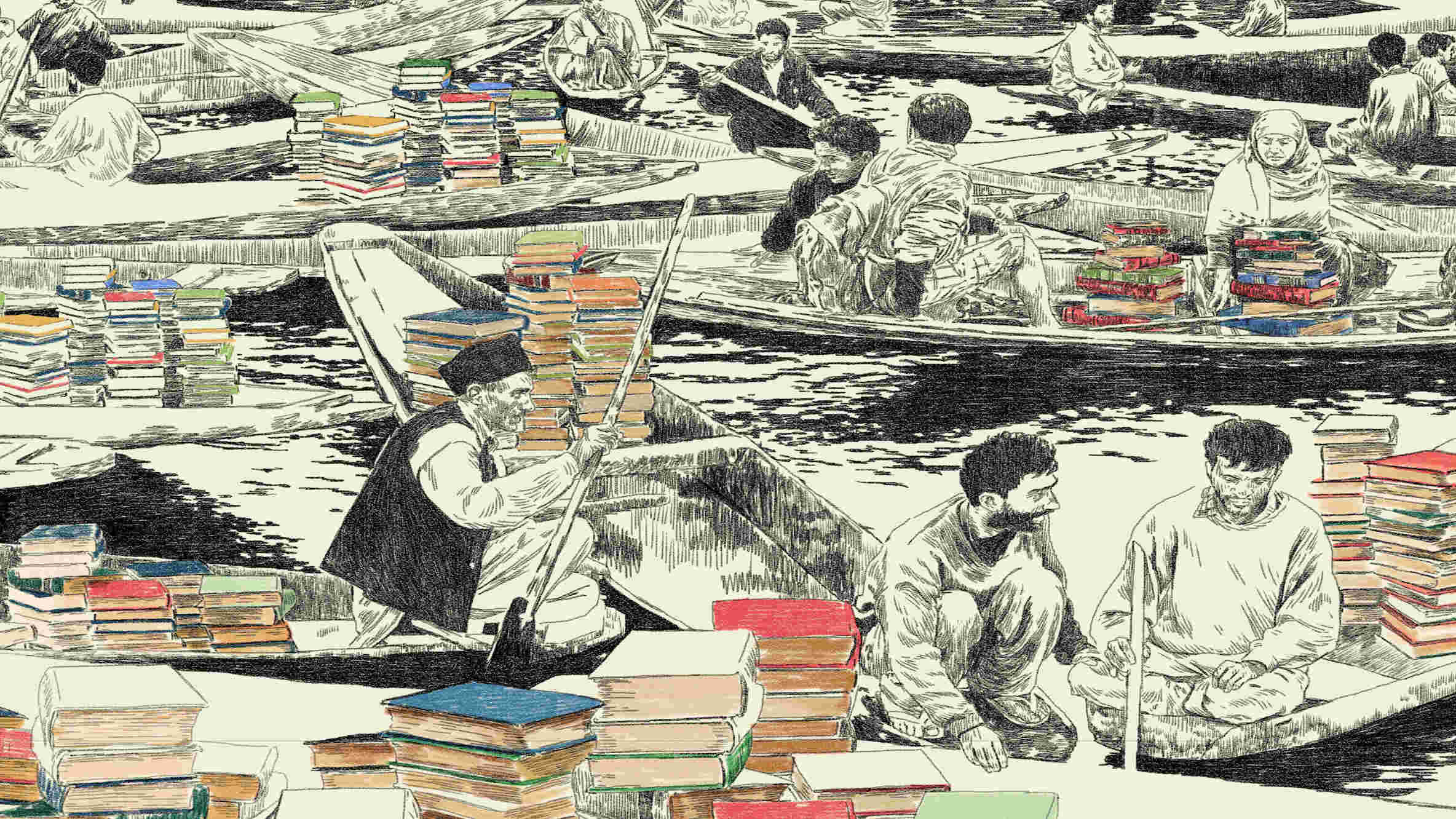

We heaped all of Mother’s books in three canoes and dragged them down the road. Past wild flowers that rose from curbside cracks, past houses with barren window boxes and shuttered windows, past a torched wool factory. We entered Market Street, where makeshift bazaars sold shrouds and feeding bottles. We were followed by a girl in a woman’s chador, a man with a pail of yogurt rice, a woman with winter-white hair who rocked an infant.

We turned onto Woodpecker Boulevard and saw the librarian, Muhammad, a lanky man with a pear-shaped face who sat leaning against a birdbath, his red caftan stained with ash. Father squatted by his side. We saw your poster, Father said. We brought you books.

Muhammad looked from Father to the books in the canoes. Relief pinched then paled his face. He returned his eyes to the ashen heaps that lay amid rubble, their scent of old paper and teakwood gone faint.

I stacked the books on wooden slats in the space of the burned-down library. Amid the ruins, against the overcast sky, the book spines rose like a bouquet of roses.

Muhammad campaigned for the new library at the makeshift houses, a cluster of brown tents set up on the outskirts, at what housing colonies remained, bruised but not annihilated. He once kneeled to knock on a fallen door; once he clambered up a rope ladder and stood on the top rung as he spoke to the head of the family. His face glowed as he recollected his morning for me every evening.

In the early days we got a mere eight to nine readers. But they became our regulars. I came up with an idea to bring more visitors, but Muhammad shook his head. It won’t work, he said.

One morning brought new visitors, a girl, ten or eleven, with a woman in a fuchsia chador, the same earl-gray eyes studded on both their faces. The girl moved from one pile of books to another. She paused by a stack, touched a hardbound. I plucked the book and offered it to her, but she didn’t take it.

Do you want something to read? I asked the woman.

I can’t read, Brother, she said, taking the book, her eyes lowered. But Miriam-jen will read to me.

You’re new to town, Sister? Muhammad said.

Visiting. But we’ll return the book before leaving, don’t worry.

No, no, Muhammad said, blushing. I was only curious about what brings you here.

I’m staying with my brother, but I came for Swallow, she said, and upon seeing Muhammad’s perplexed expression, she pinched her chin and asked, You don’t know him?

I didn’t know he was here.

The woman met my eyes and Muhammad’s and she smiled, and it was the most intimate expression that I’d seen exchanged in a while.

They stepped out of the library, the girl holding aloft Mother’s green hardbound.

Who is Swallow? I asked.

The man who can make your plan work, Muhammad said.

He took me that night to Ali Beig shrine, from whose courtyard emerged the voice of Swallow. He held in his throat a bass note, then his voice soared as he picked the note up and took it, sharp as a knife, swiftly up the octave. In being Sufi, Swallow had won the devotion of both Hindus and Muslims. Devotion: a creature so rare in those times.

In the months gone by, many a wall, stairwell, roof, and pillar had collapsed like dollhouses around chairs, tables, and sofa sets that were blackened, that had cracks running down wooden backrests, but that survived and were left standing amid rubble.

That night I entered the ruins of the sugar merchant’s villa and picked up a chair and carried it away, past a photo frame still nailed to a half-broken wall: a woman’s monochrome behind crackled glass.

The next morning he came to the library, pointed a finger at his chair, and said, That’s mine.

Now it belongs to the library, I said.

Rubbish. I’m taking it.

Swallow emerged from behind a stack of books. He said, Where’s the chair, Aziz?

In the library, Swallow, he said, stepping back.

Then it belongs to the library.

In the expression that flickered across his face, I saw a likeness between him and the woman in the moonlit monochrome. He opened his mouth to demur then lowered his head in deference to the holy man.

I said, The chair can be yours again. If you earn it back.

Name your price.

Come and read. An hour a day for twenty-one days.

Over the next few days, the library swelled with stolen furniture, bodies, voices, and the smells of local workspaces—water-chestnut fields and malachite mines, saffron hills and camphor gardens, the street, the river, the roads, the muddy tent cluster. I watched, by the steady flame of lanterns, the elongated shadows of furniture bearing silhouettes of man, woman, child, book in hand, and wondered if seeing fictional characters in their landscape would make their own interactions with the earth less painful, make their nostalgia less shadowed by recent history. Only then would they keep reading even after they had served their reading period.

That week, one of the early regulars, an architect, nailed together, with asbestos sheets and wooden frames salvaged from fallen houses, a roof and four walls. In being enclosed, the space became a place; it became a geography with the potential of accumulating history. It seemed to alter some of our readers: Was it the act of crossing a threshold to enter the library, the sight of their furniture once again penned in by a human enclosure? I watched them linger after their reading time was up; I watched them close their books and engage with each other, exchanges of story summaries leading to conversations with a personal grammar. I learned of locals who buried keepsakes by the river’s banks before rowing away toward safer lands. Decades later came grandchildren and treasure hunters who dug along the green river to discover pearl-studded ashtrays, silt-scented silk bags, silver nutcrackers, copper dancers, marble urns with jewelry from another age.

I suggested, Perhaps we should name the library?

The act of naming evoked their interest, and an animated discussion ensued. They called it Kashmiri Library, the word standing for both the people and their language.

This is like a naming ceremony, Swallow said. We should celebrate it, don’t you think?

The next day he brought a sack of corncobs, and we delighted in their scent, hay and warm grass. The nights were getting longer and colder; soon winter would be here. We shucked and roasted them over a bonfire.

I went and sat by Father. The embers crackled in our ears. He looked at me and smiled. I pictured Mother eating a corncob with Father, sometime before I was born. The image, over the years, became a memory full of detail and texture.

In recent years, when my homeland, Abbottābad, is remembered as Bin Laden’s hideout and deathbed, when news channels telecast ISIS flag-bearers parading the streets of my foster homeland, Kashmir, my past has become a source of interest to my friends and fellow teachers and students at Harper’s High School. In response to their questions, I tell them about the library, about readers who left, readers we gained; we laugh about the bait of stolen furniture. I tell them about the ethnic cleansers who came looking for the books published on the other side of the border, books that they proceeded to burn, no matter they were published before the border was born. We lost a third of our books that winter.

I tell them what became of the library in the war of ’71, which broke out between the two countries that were one country. They fall quiet. A certain kind of death leads not to rebirth, but to repurposing. The library, reopened in ’85, is decentralized and run from households: on Pomegranate Street lives fiction; on Woodpecker Boulevard is housed memoir and biography; and, befittingly, our old house by the river holds poetry.

They call the library’s survival a miracle. And I tell them that on a trip to India, many years back, as I was browsing through poetry racks, I found the volume of Dinantah Nadim’s poetry. Yes, the confiscated book, I confirm, the date of purchase scribbled on the last page in Mother’s hand. That, we all agree, is a miracle.