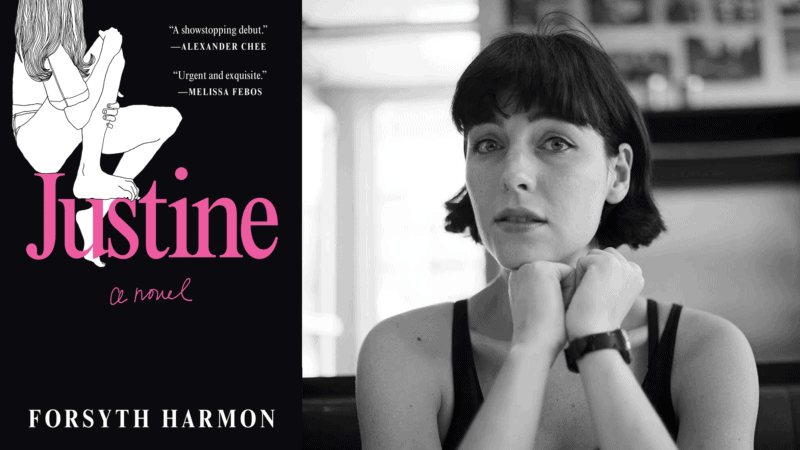

In the food court of the Walt Whitman Mall, lines from “Song of Myself” are engraved on the wall—and covered by the giant “M” of a McDonalds sign. Golden arches interrupting sprawling queer verse: It’s an apt hangout spot for Ali, the teenage girl at the center of Forsyth Harmon’s illustrated debut novel, Justine. On the North Shore of Long Island in 1999, wild desire can only run so free.

That is where, at the checkout of a Stop & Shop, sixteen-year-old Ali beholds her worst and most beautiful nightmare: Justine. Immediately drawn to the tall, “spooky” cashier with a “queenly attitude” and a “chin-length pitch-black bob,” Ali takes a job at the supermarket so she can be as close to Justine as possible. She looks at Justine the way she looks at the models on the magazines she pins to her bedroom wall. Her lust is aspirational. In a quest to become as skinny as Justine, Ali starves herself. She lives exclusively on Dannon Lite fat-free strawberry yogurts while Justine leads her on an endless bender around Long Island. Accompanied by the boys they date to turn away from themselves, they’re never alone, always hiding from their deepest urges. The abandon of Ali and Justine’s reckless summer spree belies a tragic repression.

Throughout the book, black-and-white drawings of soda cans, cats, pepperoni pizza, upside-down Smirnoff bottles, Tamagotchis, and unraveling cassette tapes begin to do, for the reader, what Ali’s evasive words can’t: They express suffering, searching, yearning. Harmon, who also illustrated Melissa Febos’s forthcoming Girlhood and Catherine Lacey’s The Art of the Affair, juxtaposes images and text to create a book that has the breezy intimacy of a ’90s zine, with narration that is alternately withholding and searing—and altogether haunting. In the tradition of Daniel Clowes’s Ghost World, Julie Buntin’s Marlena, and T Kira Madden’s Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls, Harmon explores what it means to navigate a female body through queer adolescent longing, amid the stifling uniformity of suburbia.

Over the phone, Harmon and I talked about Allen Ginsberg’s “Supermarket in California,” the nefariousness of Diet Coke, Long Island’s maddening contradictions, and what’s so addictive about rewriting your own coming of age.

—Logan Scherer for Guernica

Guernica: Ali’s desire for Justine is tied up with her desire not only to become Justine, but to stop being herself, to cancel herself out—especially through starvation. How do these forces of desire and self-loathing fuel each other?

Forsyth Harmon: Ali grows up with her grandmother in an isolated and lonely environment. When she meets Justine, it really is a kind of love-at-first-sight. She’s filled with these dual desires: to be, and to be with, this other person. But it’s not just about desire. It’s about escaping her circumstances, and herself. Self-starvation functions similarly. Ali pins these images of supermodels to the walls in her bedroom and, again, she desires to be these women and also to escape into the fantasies they play out. She feels like if she can mirror their images, she can live the lives they advertise.

Guernica: Do you see this interplay between desire and self-cancellation as particularly queer?

Harmon: I do see these self-starvation urges as being tied up in Ali’s queerness. Her sexual desire for Justine is repressed. She feels it in her body but she doesn’t really allow herself to reflect on it. In fact, she’s barely conscious of it. At sixteen or seventeen, she’s in this transition period of girlhood to womanhood and she starts to both occupy and desire another almost-adult female body. Self-starvation is this way to freeze her transition and her desire simultaneously.

Guernica: Ali is destroyed by starvation while working at a landmark of endless consumption—Stop & Shop—a landmark that takes on a towering sublimity. There is something stunning and horrible about the grocery store, with its Boboli pizzas, Sprite, Trident, Dannon Lite fat-free strawberry yogurt. And then, of course, there’s the Walt Whitman Mall. How did you conceive this juxtaposition between deprivation and consumerism?

Harmon: I can’t help but think of Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Supermarket in California.” It so beautifully reflects on how these grocery stores hold all this imagined potential that they never live up to, and Ginsberg addresses the poem to Walt Whitman. Here are a couple lines from the first stanza: “In my hungry fatigue, and shopping for images, I went into the neon fruit supermarket, / dreaming of your enumerations! / What peaches and what penumbras! Whole families shopping at night!”

So here’s Ginsberg looking to this supermarket with a physical, and I also think, spiritual, “hungry fatigue,” hoping that the store will hold some glimpse of the world Whitman creates in his poetry—nature, democracy, love—but then we’re shopping not for food, but for “images,” under harsh neon light. There are peaches, but at the same time there are these whole families shopping—the expectation of having this perfect nuclear family overshadowing the pleasures of the natural world.

Ginsberg goes on to find some beauty, following Whitman, “in and out of the brilliant stacks of cans.” This poem actually comes seven years before Warhol does his soup cans. But then Ginsberg asks, “Where are we going, Walt Whitman? The doors close in an hour.” And so I think he’s acknowledging that this beauty can’t last. He feels “absurd” for believing it could. He ends the poem with an image of the river Lethe, which runs through hell, and drinking from it makes us forget. For Ginsberg, the point is that this is what modernization and industrialization do: make us forget what’s natural, make us forget the past. We don’t know where the peach came from.

Sure, we can have anything we want when we want it, but at the cost of its meaning. So, here, we’ve got Ali surrounded by food but starving. I love the layering of Ginsberg over Whitman, and thinking about that in the context of Ali’s experience.

Guernica: And these two queer voices trying to marry their queerness to Americana.

Harmon: Yes! And there are these great lines where Ginsberg totally goes there, when he’s addressing Whitman, ”eyeing the grocery boys / I heard you asking questions of each: Who killed the pork chops? What price bananas?” I really love that poem.

Guernica: I’m obsessed with your descriptions of Diet Coke. This drink that is totally ’90s Long Island, and yet also totally time- and place-transcendent, becomes a hypnotic recurring image throughout the novel—and a literal image through your illustration. At one point, Ali even calls her own body “fizz, frothing, effervescent, a can of just-opened Diet Coke.” What is it about Diet Coke that compels Ali to become its very container?

Harmon: I don’t think there’s a way of answering this without addressing the Diet Coke call button Trump had installed in the Oval Office. When he pressed it, it would summon a butler who’d bring him a Diet Coke on a silver platter. He reportedly drinks a dozen Diet Cokes a day, and had joked to a reporter that everyone thought the button was the nuclear button. With that, we’ve already cast the beverage as being nefarious.

This harkens back to the Ginsberg poem: a mirage glistening with condensation, it promises this refreshment, this energy without any calories. It’s this materialization of a free lunch, and yet, over the past few years, studies have linked diet soda consumption to weight gain, diabetes, heart problems, dementia, strokes. For me, it becomes a symbol of what Ginsberg is interrogating in his poem.

Admittedly, I drank a shit-ton of Diet Coke when I was Ali’s age, so no shade on Diet Coke drinkers.

Guernica: Well, it is irresistible. “Glistening with condensation” makes me think of all the glittery surfaces in the book. The Stop & Shop parking lot glistens in the streetlight, the pink satin sheets shimmer in the Victoria’s Secret display at the Walt Whitman Mall. What do you see in the twinkle of pop Americana?

Harmon: Ali is so taken with these surfaces. There’s this beautiful promise in all of it; it’s the promise of this country: this idea that you can be anything you want despite the circumstances of your birth. Ali really believes this. I once believed it, too.

Guernica: Delusionally, at some level, I still believe that, too. It’s like a religion.

Harmon: I still do, too. Who even tries to write a novel without believing that? Who doesn’t curate their Instagram posts without believing that on some level, even as we know that we’re working for Zuckerberg?

Guernica: The late ’90s is such a wonderfully charged moment for a story of queer adolescence—on the cusp of wider liberation, but not quite there yet. At the same time, there’s something that feels so contemporary about Ali and her desire. What made you decide to locate Ali in 1999? What does it mean to revisit this moment now?

Harmon: In part, I put the book in 1999 because that’s when I came of age. Part of this project was dealing with some things now that I hadn’t been able to process at that time. It also takes place just before Bush takes office, not long before 9/11. I know the popular imagination looks back now and thinks, “Oh Bush and Reagan weren’t so bad. At least they were civil, right?” I just watched The Reagans. Reagan is polite, sure, but “states’ rights” and “law and order” meant the same things then that they do now. And Reagan’s handling of the AIDS crisis—he essentially presided over nearly 90,000 deaths without doing a thing. There are some echoes of the coronavirus there. Some things change over time, but so much remains the same.

There is also just something timeless about the adolescent experience.

Guernica: My favorite novels are about that. I feel like, in a weird way, it’s kind of the only thing worth writing a novel about: coming of age.

Harmon: Certainly so many of us start there. I love Stacey D’Erasmo’s work. I took a class with her once. I’m not quoting her exactly right, but she said something to the effect of, “We just write the same book over and over.” I see some truth in that. Having finished this first book and now working on a second, I am reflecting on how much both books have to do with the dynamics and patterns that were created in my adolescence—the set of firsts that I keep trying to relive or finally set right. That just becomes more and more clear to me over time.

Guernica: I was struck by the intimacy and urgency of your drawings—even (in fact, especially) the ones of commercial objects. There is such a sense of movement and confession in them. How do you think of the relationship between image and narrative?

Harmon: I want to distinguish this project as an illustrated novel, something that’s different from a graphic novel. It doesn’t follow the standard image-cell-checkerboard format. It’s closer to something like an illuminated manuscript, or even some of the illustrated literature of the nineteenth century. Charles Dickens comes to mind.

I have these full-page and spot illustrations show up whenever they need to. I wanted them to tell their own story, specifically because Ali is so repressed. The images stand in for emotions that she’s not able to express. They’re black-and-white, and usually at close-range, because she doesn’t have a lot of perspective. I tried to make them do the work of emotion for her—especially in the image sequences: the cassette tape unraveling, loose-leaf crumpling, a make-up compact opening.

Guernica: I loved the confessional text embedded in them.

Harmon: To be clear, those confessional texts are almost all Smiths lyrics, to take it back to working-class, repressed queerness. I’m disgusted by Morrisey’s current political views—what a disappointment—but those early Smiths songs were so important to me on Long Island. The music holds importance for the Justine character, so I snuck them in. There’s some inspiration in there, too, from Grace Miceli. She puts emotional text into images of consumer products. I really like her work.

Guernica: The images also remind me of ’90s queer zines.

Harmon: I made a lot of zines in college. In initial drafts of this book I was doing full watercolor illustrations, but I came back to that black-and-white look. Part of it was about a minimalism in line with the text, but part of it was a return to my Xerox black-and-white printouts. I do still have a couple of those old zines hanging around. When I look at them, I can see that this project was a continuation of that one. In the same way that I revisited certain experiences of my life at that time, I also revisited those zines.

Guernica: Having grown up as a queer person on Long Island myself, I found your depiction of Northport uncanny, riveting, comforting, horrifying. I’ve honestly never seen such a spot-on depiction of the kind of suburbia that’s specific to Long Island. What fascinates you most about that place?

Harmon: Long Island is so physically close to New York City—and yet in some ways it’s so far away. On the one hand, it’s quite actually an island isolated by bodies of water on all sides. At the same time, the island contains Brooklyn and Queens. I find that kind of funny: Do you know anyone in Queens or Brooklyn who says they live on Long Island?

One big difference is transportation. Subways don’t extend beyond Queens and anyone who’s faced a New York City commute from Nassau or Suffolk County knows that neither the Long Island Railroad nor the Long Island Expressway are ideal. Making consistent passage to and from the City is difficult, which increases the isolation. Despite that, growing up, I had this strong sense of New York City pride, thinking that my proximity to the City equalled access to its culture and power. But it was not true.

Long Island is actually politically and culturally more like the South and the Midwest than New York City. And, Suffolk County was one of the richest counties to vote for Donald Trump in the entire country in the 2020 election. This is what most terrifies me about Long Island: It’s this land of natural beauty and financial plenty—both of which are, of course, very unevenly distributed—and most of it votes to make it easier for those in power to harm those who aren’t.