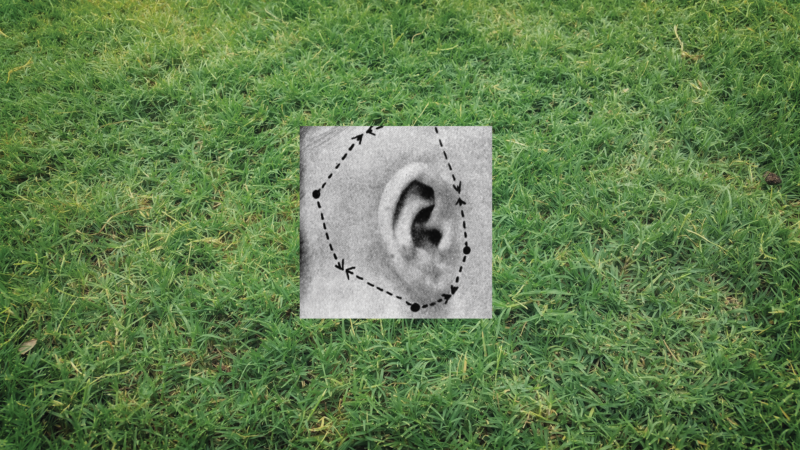

“VERY SLOWLY, we MOVE very close to the ear, gliding slowly around the crevices approaching the dark hole. A huge, low rushing of air SOUND, THEN DARKNESS.” —Blue Velvet, David Lynch

1.

There is a foreign body in my ear.

The doctor wrote it in his diagnosis, like this, in capital letters:

FOREIGN BODY EAR

He prescribed antibiotic cream and told me to lay on my side with hot compresses.

Soften it up. We will coax the foreign body out.

2.

The guide tells us that Jerusalem is a microcosm. That whatever happens in Jerusalem is a crystallization of whatever is happening in the whole country. In the whole world, in fact. Global shifts, Trump’s election. All immediately reflected here.

Eight of us, plus the guide, in a van heading down Derech Hebron Road. It’s a tour of Jerusalem called Meuchleket.

Uni-divided.

A play on words that contains within it the absurdity of life in this city, a badly stitched-up Frankenstein, bursting at the seams.

It feels strange to take a tour of a city I’ve lived in for almost twenty years.

3.

What happened is that my ear, without prior warning, decided to annex the silicone back of my earring. My ear became inflamed. Swollen.

I had just added two new piercings. I keep adding new holes. “Instead of having children,” I joke to those who ask me why.

A well-meaning friend tells me to use the holes I already have.

My eye sockets. My mouth. My.

But I long for holes in which I can hang beautiful things. Silver dangling. Holes I choose. Holes to remember. Holes I can control.

4.

Holes in my story. You can live in Jerusalem for twenty years and barely wonder. Life in Jerusalem is complicated enough as it is, without wondering.

Here are some issues that have concerned me, without wondering, during the time I’ve lived here: The soaring rent prices. The For Sale sign on my door. Intifada. What they call “negative immigration,” specifically the hordes of students pouring out onto the highway toward Tel Aviv the day after they graduate, thereby emptying the city of almost any potential for deep cultural growth. Another intifada. A sense of religious oppression, including a personal, aggressive campaign waged against me twelve years ago by a rabbi who disapproved of my relationship with A., my then-boyfriend. The sense, as a woman, of moving through the city as a foreign, unwanted body. Neighborhoods, mostly ultra-Orthodox, I am forbidden to walk through unless I am dressed a certain way. Body parts censored. My eyes. My mouth. My. Eyes that close. Heads that turn away. Streets that are crossed when I approach. Whether I am ugly or beautiful. Whether I’ve combed my hair neatly, or let it hang knotted like an old hag. Women’s faces and bodies blacked out with spray paint on bus-stop advertisements. Ears that close. Women’s voices excluded from municipal events and ceremonies. My presence as an actual foreign body in the city, not born or raised here, nor having ever managed to put down any roots. Or root. Not even one root. A foreign implant that hasn’t taken. The city rejects, ejects. Infects.

5.

Here are some words I write in my notebook during the tour: Double. Jerusalem was divided twice in 1948. Geopolitically. Racially. Triple. Jerusalem is a three-headed monster, with three city centers. Ultra Orthodox. Arab. Zionist. Lines. City Line. Seam Line. Lines of poetry arbitrarily censored in Palestinian schoolbooks taught in East Jerusalem. Walls. Western Wall. Separation Wall. Invisible Wall. Graffiti on wall covered by the army with rectangles of purple paint.

6.

Holes in the wall.

“Border” is a visual poem filmed, or staged as if filmed, through cracks and gaps in the wall of the border, which, from 1948 to 1967, divided Jerusalem in two.

I encountered this segment in Israeli director David Perlov’s 1963 documentary In Jerusalem while searching for found footage of Jerusalem shot during the sixties, for a project I worked on in film school. Commissioned as a kind of propaganda film by the Israeli Film Service and the Zionist Histadrut, In Jerusalem was considered groundbreaking here when it first came out, almost revolutionary. Perlov, strongly influenced by French New Wave cinema, created a sequence of what might be called poems about the city using a self-reflexive, non-linear form. At the center of the film is Jerusalem.

“The ruins are very photogenic,” the narrator states drily in “Border” as the camera focuses on a hole in the wall. The Old City peeks through.

“The pain is invisible in postcards sent from the border.”

Perhaps I received one of these postcards before I came to Jerusalem. As a child in a faraway land, across an ocean. A postcard selling myth devoid of pain.

7.

The guide of Meuchleket tells us how they just want people to agree to listen. She tells us people are afraid to even hear.

8.

The antibiotic cream is not working and my ear continues to swell. It has begun to morph into something monstrous, not ear-like. Distended, a pregnancy. My ear has a mind of its own.

The well-meaning friend tells me to rush to the emergency room. She reminds me that I have a tendency to neglect my body.

She heard of a woman whose entire ear was devoured by an infection of this kind.

And another who was hospitalized for weeks, hooked up to an IV drip.

I make an appointment with a plastic surgeon.

9.

What happens to body parts you neglect?

A woman in her late thirties, for instance, who chooses to disregard The Ticking of Her Biological Clock, might find herself at some point stuffed with hormones, spread-eagled, anesthetized on a hospital table, doctors yanking swollen eggs out of her uterus.

When she wakes up she might find that her ex-boyfriend A. has come to drive her home. The doctors will not be able to hide their surprise at the sudden appearance of this man, whose presence calls, even more, into question why a woman of this age is sending her eggs off into frozen Siberian exile instead of joining them, if not in holy matrimony then at least in a sterile test tube, with this man’s, or any man’s, virile sperm.

10.

“In Jerusalem,” the Other is a distant figure viewed through a crack.

Today this wall no longer exists, officially. Or it exists, but it’s invisible.

11.

In Jerusalem, there is a border between the eternal myth of the city and the reality of everyday life. A border that is blurred as myth forms reality and reality forms myth.

While the guide of Meuchleket speaks, we are attacked by scores of tiny flies that cling to our clothes, our hair.

“A sign of spring,” the guide says with a smile.

My ear is burning. I came here because of a myth I don’t remember anymore. Or perhaps I peered through a hole in the wall and the myth shattered. Or the myth remained intact and I shattered. The rest of the group seems unperturbed by the flies. They continue to listen, riveted, to the words of the guide.

I try to pick the flies out of my hair, one by one, but this becomes futile, as more and more land on my body. Tiny wings, legs, antennas tearing apart, sticking to my strands. Sticking to my ear, which is moist with antibiotic cream and Vaseline.

12.

Peep show. If a city is a woman. If the body of a city is the body of a woman is the body of a city.

No. This is another myth.

13.

The holes from Perlov’s film remained with me.

I wrote a play set in 1967, in which the main character, twenty-one years old, Jewish, recounts a dream-memory of trying to catch a glimpse of the Old City through a hole in the wall with her childhood friend.

“All I can see are people’s legs,” she says, “and I feel like I’m peeking at something forbidden, like I’m peeking into the nakedness of the city.”

The director chose to stage this moment so that the actress says these lines with her back to the audience, bent at the waist, legs spread. Her face glimpses out from between her knees as she speaks. Her skirt rides up. Her underwear is showing.

She is both the voyeur and the exhibitionist. The eye and the object. She is the wall and the city. She is both sides of the wall.

She has tried to flee Jerusalem, but the city haunts her body like a ghost.

14.

The surgeon first numbs my outer ear with a painful injection. While he does this I think of that other extraction, exactly one year ago.

I say a prayer for my eggs, languishing in a netherworld of ice.

I wonder where A. is. I never know where I’ll reach him these days, though last week he asked if he could register his name at my address, for bureaucratic purposes, at the Ministry of Interiors. Because he’s living off the grid now, a kind of private protest against urbanity. He wanted an address in Jerusalem and I said yes, because I have an address to give. An address of a crumbling-down house. With a “For Sale” sign on its door. That I might be leaving soon. Because I am always trying to leave Jerusalem. I’ve been leaving Jerusalem for at least five years.

Both of us are, to borrow a phrase from Isaac Babel, “people who have fallen through the cracks of life.” And after all these years, no, we are not together. But now registered formally at the same address. This one address in Jerusalem that unites us even though neither of us, probably, will be here soon.

I try to avoid talking politics with A. I’ve learned it is useless to argue politics with people you love. But when he was here last week, the words slipped out of my mouth, slipped out into a full-fledged fight, bottle of arack near empty on the floor between us. I told him that as a woman I find myself identifying with those who move, voiceless, through the world, through the city. I told him I know how it feels, and that he does too. I cut him off when he opened his mouth to protest.

“You really don’t want to go there with me,” I said. “I’ll crush you.” I heard myself saying: I will crush you.

I’ve never used words like that with anyone before. Perhaps it was the arack. Perhaps it was my ear, which, throbbing, sent pulsating urgent messages to me through Morse code.

“Are you mad at me?” I whispered, mouth to A.’s ear at the door, when he hugged me goodbye.

We both knew he must go. Both of us crumbling at the door. We are not together. We part, at our address. We have this invisible boundary between us, and we have this space that exists, that holds us together through time, in Jerusalem, officially. According to the Ministry of Interiors, at least.

15.

My stomach clenches with nerves, still, each time my play is performed in Jerusalem. All that raw female messiness laid bare in the city, on its landscape, like a misshapen birthmark unveiled on naked skin. I’m slowly trying to learn to relish the discussion this generates. The precarious privilege of having a stage upon which to perform.

After a Tel Aviv show, I was told I should have gone easy on all that Jerusalem talk. Perhaps I should even consider setting the play elsewhere. No one is really interested in Jerusalem here, they said.

16.

I called A. before the ear procedure but his voice mail answered. He is off somewhere in the wilderness without reception. Out of reach.

Such is life in the cracks, I think to myself as the surgeon prepares his tools.

I feel nothing when he yanks the thing out of my ear.

Afterward he waves it at me like a war trophy. The bloody, mucus-covered body to which my ear has given birth.

“In the ER, they would have sliced you open like a bread roll,” he says.

17.

“I don’t know why it had to be an ear,” David Lynch said in an interview, about the image that frames his film Blue Velvet.

That severed, human ear, found flung in a field, is the portal to a disturbing underworld, a realm of shadows which, once entered, cannot be unseen.

“It needed to be an opening of a part of the body,” Lynch said. “A hole into something else…. The ear sits on the head and goes right into the mind so it felt perfect.”

At the end of the film, we exit the vortex again, with “a huge low roaring sound.”

“SLOWLY WE COME UP OUT OF A HUGE DARK HOLE. We see we are rising out of an ear.”

18.

I leave the clinic, ear bandaged but intact, mostly.

I feel pounds lighter. Hollowed out.

This stitched up foreign body lurches her way through the city, toward a crumbling structure at an address that she may or may not call home.