My grandfather shot himself in the head with a handgun. He’d been an addict for years: booze, cigarettes, and, finally, pills, but it was the cancer sticks that got him. Lung cancer you can’t come back from. Emphysema. The former was terminal, and the latter made him miserable. He took matters into his own hands.

He had five grandchildren. I’m the only one he mentioned in his suicide note. I’m the only remaining male Osmundson. I have a sister.

“Make sure Joseph,” he wrote, “carries on the family name.”

I only met him twice, and the first time I was too young to remember. Still, I can picture his face and cheap leisure suit, see him folding his final note into three, placing it in an envelope, placing that envelope on a desk, then walking to his bedroom and putting the gun to his head. There was no blood on the letter he wrote to his son, and, through his son, my father, to me.

I first dreamed of my own pregnant body at nine. I saw it, side on, in a mirror. Picture me as I saw myself in my sleep: I was a nine-year-old kid stretched vertically by age, and out at my belly by the thing I held inside. I saw myself at eight-and-a-half months, stopping midway up the stairs to catch my breath, hungry for everything, but especially pickles and ice cream together.

I was a little cisgender boy.

My mother taught Lamaze classes. They started shortly after work hours, and my dad couldn’t make it home from work for a seamless child hand-off. By then, my sister had her after-school program. Too poor for a babysitter, I ha to accompany my mom. I was her teacher’s assistant, a job I thought real, and that I thought conferred some amount of importance and authority.

Pregnant people came to the class, and—over the weeks—their bellies grew. Women came mostly with their husbands, but we used the word “partner,” which didn’t mean anything about the relationship of the two people. A pregnant person’s partner might be a lover or sister or friend.

When their partners couldn’t make it, I played the part. I sat on the floor in the overheated portable classroom in the hospital parking lot. A good partner, I breathed along with the pregnant people, making sure they didn’t speed up too much, holding their breath steady.

“Just focus on the pattern of the breath,” my mom said gently, moving around the room, the only body standing, the rest of us couples on mats on the floor.

“Hee hee hee hoooooooeeeeeee,” I said to a woman, with a woman, rubbing her back in slow, counter-clockwise circles.

“You’re doing so good,” I said, my pre-pubescent voice genderless, high.

“Breathe out now, one, two, threeeeeeeeeee.”

The exercise over, I squeezed her hand one final time, signaling the completion of something. In my waking hours, I knew my body wouldn’t go through this change. I knew myself incapable of incubating a human life this way.

If I couldn’t be pregnant, I could be the next best thing. I could be, someday soon, I hoped, a father.

Washington Post email alert: Nov 26, 2019

News Alert: ‘Bleak’ U.N. report says world on pace to warm nearly 4 degrees Celsius by 2100, urges rapid action to avoid worst of climate change

And then, a virus. I saw it coming in February. I’m a microbiologist by training, my PhD in viruses and bacteria.

In my grad course on virology, we were taught not by one professor but by a series of the nation’s best virologists, two lectures a week. “It’s not if,” they said, one after the other, of pandemics, “but when.”

One of my best friends, his PhD in molecular development (he studied how we build our own ears), said, “This is like climate change in fast forward.” That was in March.

“We’ll see how we deal with this,” he said. “It will be harder to ignore.”

But our government ignored even this obvious crisis as it obviously killed people. Our nation feels like a suicide pact, a death cult. The instrument of death (whether COVID or climate change) feels almost irrelevant.

I’m thirty-seven and somehow a college professor. The PowerPoint slide says “The Carbon Cycle,” and I stand in front of sixteen twenty-somethings with tape measures in their hands. In twenty minutes, we’ll be outside measuring the diameter of two dozen oak trees in an urban forest on NYU’s campus.

“The Carbon Cycle.”

I explain. The earth’s atmosphere is a closed system. There is a fixed amount of carbon on earth and in the air.

There is one way to get carbon out of the air: fixing Co2 from the air into sugar.

To put carbon into the air, you burn the energy in sugar, by metabolism or industry, releasing energy and Co2 as a byproduct.

Yes, I say: When you go jogging, your body burns glucose made by plants and releases Co2, using the energy that comes from breaking down sugar to pull your muscles and propel your body.

“So, does jogging cause global warming?” a student asks.

“No,” I smile back.

For tens of thousands of years, humans existed in carbon equilibrium with the earth. The carbon cycle was balanced: We existed alongside many other plants, fungi, animals all using carbon for our metabolism, and we existed alongside plants, algae, and cyanobacteria fixing carbon out of the air into sugars.

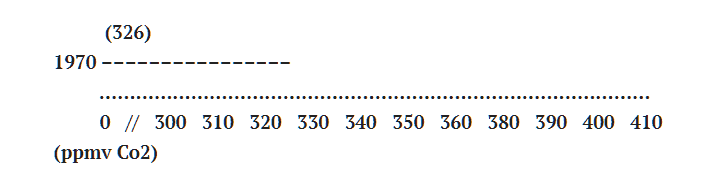

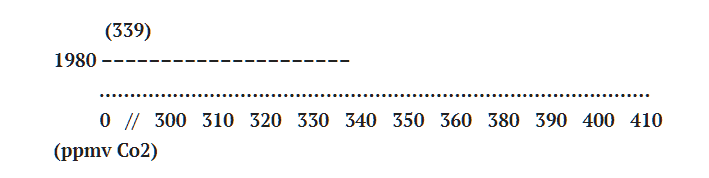

But then human animals realized the wealth of carbon our planet contained. Coal. Natural gas. Petroleum. All of these sources of modern human energy involved digging down into the earth for ancient carbon.

Where did that carbon come from?

It’s the carbon of long-dead things, plants and plankton that died millions of years ago, trapped in rich soil, forgotten about. Plants had taken carbon out of the atmosphere, and their deaths had trapped it underground.

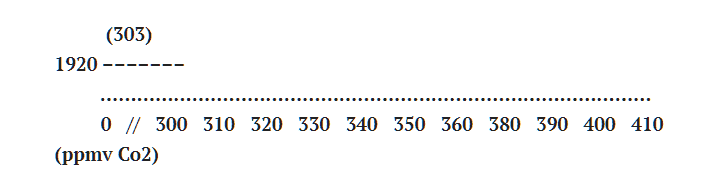

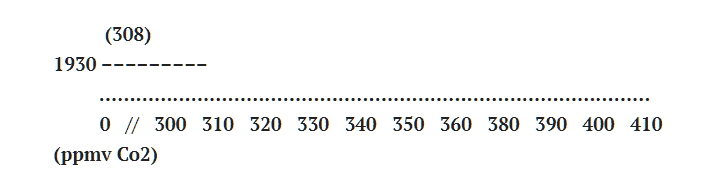

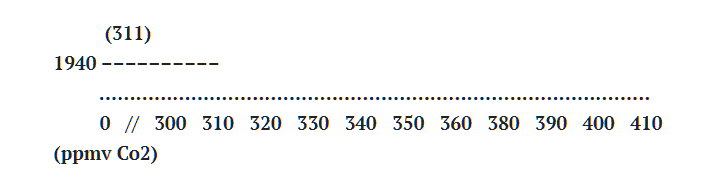

In the industrial revolution, starting around 1740 or so, humans began burning coal and fuel for energy to run machines that produced goods that could be sold, producing capital that could then be used to buy more goods.

A little industry led to more. More industry led to more. A feed forward loop of early capitalism. A feed forward loop we didn’t know—then—could end up eating us all alive.

Washington Post email alert: Dec 3, 2019

News Alert: Avoiding catastrophic impacts from warming gets harder as carbon emissions hit another record

“We’re blowing through our carbon budget the way an addict blows through cash,” said Rob Jackson, one of the authors of the report.

I pulled my body out of Saleema’s body. It was summer before her senior year of college, and we were in a dorm room at her summer teaching program. We fucked first thing in the morning, when the sun woke us up by shining too brightly at our window. Her roommates didn’t stir, and so we could take this time for ourselves without worrying about the noise we’d make.

It was Saturday, and we’d planned to work for a bit at a coffee shop and then head to the north beach at Lake Calhoun for a dip.

“Fuck.”

It was 2006, the year An Inconvenient Truth came out. Saleema wasn’t on the pill. It made her sick. The pill made her feel like shit so we used condoms.

It was annoying to find time to fuck in that tiny shared apartment, the walls so thin. But not that morning. I thought it was just that, that fear gone, that made her open up, that made me feel so good inside her.

The condom broke. I’d cum inside her.

“Fuck,” Saleema said. “Joseph!”

“I know!”

“God damnit. We have to go to the pharmacy on our way to the beach.”

“Ok.”

“It’s no big deal,” she lied.

Later that day, we sat on the beach together, and her body pulled its muscles too tight. Cramps. The sun was everywhere, reflecting off everything, hitting us even under the wide beach umbrella Saleema brought from home.

“God dammit,” she said, squinting her face against the pain, not the sun.

“Do you wanna go in the water?”

“Yeah.”

We walked together, and, once we were in the water, her body felt a little better. I held her in my arms and lifted her feet off the sandy floor. Minnesota was lake country, and lakes are fine for swimming, but the water was murky and didn’t invite us deeper. I carried her, almost weightless, as she giggled, as I kissed her, as she pulled me closer. I got hard under the water, and she reached under to touch it, moving her hand up and down before letting go.

I pictured our child, half her, half me. We both wanted kids. We just didn’t want kids yet.

“What if we had one?” I asked, holding her body in the water, lifting her up, her feet on my thighs. She wasn’t heavy.

“Joseph!”

“We’re too young, I know, but what if!”

“It would look white!”

I laughed.

“The horror,” I said.

“My mom would be so happy,” Saleema said.

“Mine too. She’d probably move to Minnesota to raise it.”

“She’d have to compete with mine.”

I felt her bounce on my legs under the water.

“It wouldn’t be so bad.”

Our lives would be different, but maybe not worse. Our lives would be something more than the sum of her life and mine.

What does it mean to mourn a child who never was? Or is it just another way I can miss, and mourn, her?

I don’t regret our decision. We weren’t ready. I wonder, though, if that might not have been my last real chance, and I imagine another version of this story, one where I’m carrying her body around that Minnesota lake, the water that murky green-brown, and in Saleema’s body another body, that little thing: her, me, us.

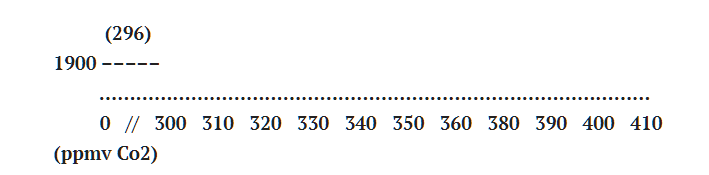

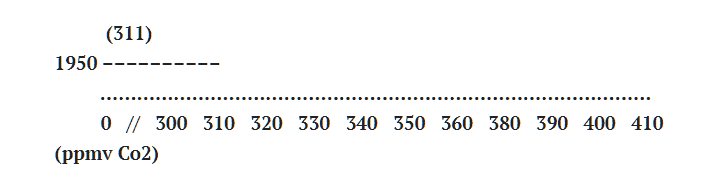

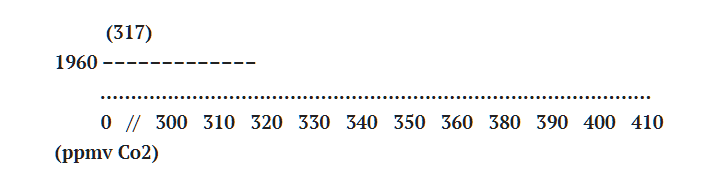

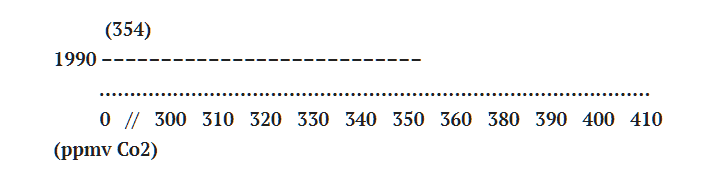

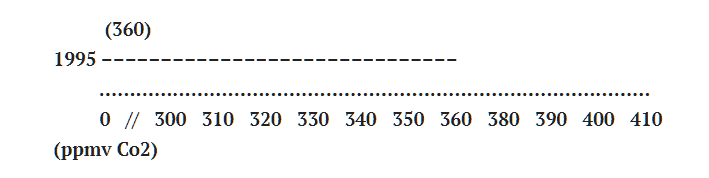

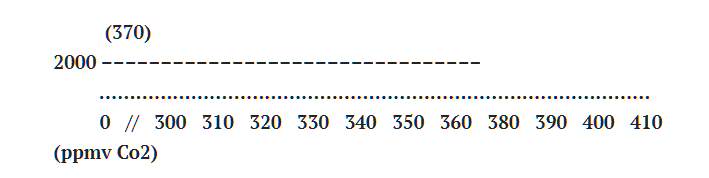

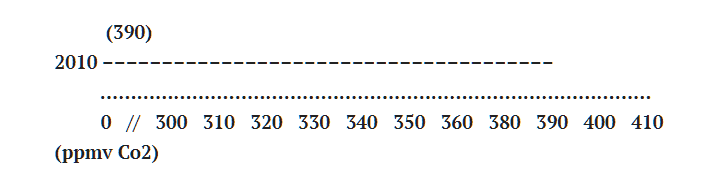

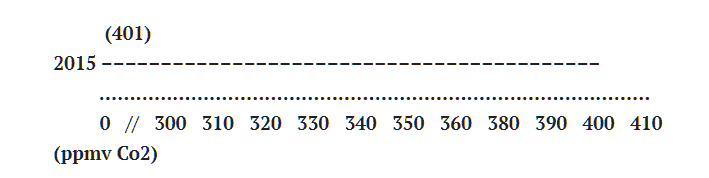

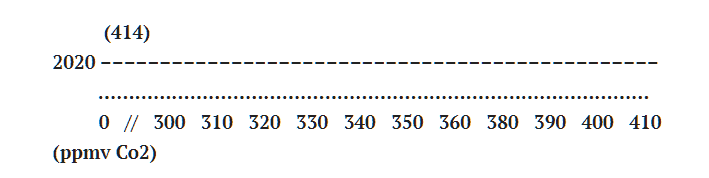

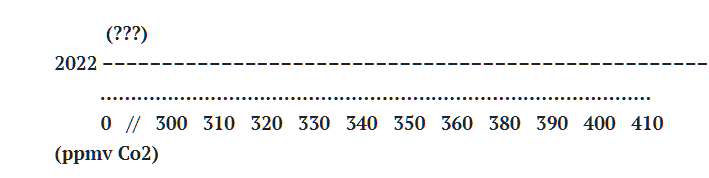

ppmv? Parts per million by volume. Basically, what percent of the air is that particular thing. We tend to think about air being mostly oxygen, because that’s what we need to breathe. But no, air is mostly nitrogen, 78 percent or 780,000 ppmv, and only about 21 percent (210,000 ppmv) oxygen.

Co2? 300 ppmv or 0.03 percent.

So what the fuck? What’s the big deal about 0.03 percent of our air?

Co2 in the air is a greenhouse gas. Thus that lil’ 0.03 percent of our air can lead to a lot of global warming.

The slide said “The Carbon Cycle” and I asked my students to form a hypothesis for their work that day.

These students, teenagers, accepted the reality of climate change. It’s the only world they know. We had no climate deniers in our midst.

“Can planting urban forests combat rising Co2 levels?” was the question we came up with.

I knew the answer already: This urban forest didn’t fix much carbon at all, and planting a million like it wouldn’t do shit to slow climate change.

Walking out of the classroom, each student seventeen years my junior, each student holding tight to a tape measure, we set out to measure the diameter, and so the radius, of trees, to see just how bad their future might be, and what exactly they can do about it.

I already knew the answer.

I text Claire: “Do you wanna have babies?”

I’m thirty-seven, and a lot of my friends are that age, too. For some folks, the biology of baby-making shifts around this age.

She texts back: “We’re maybe gonna try for a bébé next year”

Joseph Osmundson: “OMG”

Claire: “But my uterus might be all dried up”

Joseph Osmundson: “you’re young!!! Are you scared of climate change re: babies”

Claire: “Yes. I mean. It’s a selfish thing to do. But you know what if we don’t get pregnant I’ll just get loads of cats.”

It’s not just climate change she’s afraid of. It’s everything. For example: “What if I have a son and he’s a bro?” She’s mad that Stephen, her partner, won’t let her name the baby Florian.

“I am team Stephen,” I write back.

“I want my son to be an effete Victorian gentleman,” she writes, and yes, I agree, but I say for that to happen you’d have to name him something normcore, like Kevin.

I ask why it’s selfish. Isn’t it a selfless act, giving your whole life to raising another human?

She writes: “No if we’re talking about this as an intellectual problem for an article. I want to acknowledge global warming as a factor in having kids which it is. But also acknowledge my white rich lady privilege on not having that be my main concern. I have the luxury of worrying about whether or not I want bébés and being able to factor global warming into that decision.”

She writes: “But also like even if no global warming there would still be dangerous hellscape in other ways. There’s always been an existential threat for women and children and especially historically.”

“Yes,” I say. “I never thought about it that way,” and of course I hadn’t.

“Yes,” she says. “People say, ‘oh the worst things you can do for the planet are having kids, eating meat, and flying.’ And they tally it up. Like ‘oh I don’t have kids or fly so I can eat meat and feel virtuous.’ But it doesn’t work that way. And that’s why global warming is happening because it’s not a personal failure.”

My mother always insinuated, growing up, that couples with no babies were selfish, they cared only for themselves. My parents were both resentful of the financial ease their childless friends had, jealous of their vacations, too-large homes, new cars. Now it’s selfish to have kids, it signals we care nothing for the earth they’ll inherit.

And then a virus. They say COVID-19 is good for the earth. They say the earth is breathing better now. Air quality in Los Angeles and New Delhi better than in years, decades, haze gone, haze that’s been a fixture of those city since the industrial revolution.

They say we are the virus. Fewer flights, fewer people on flights. They say getting outside is safe now: Go on a hike! Enjoy the outdoors!

Co2 emissions are down by 17 million tons of carbon dioxide; they say they say that’s back down to 2006 levels.

None of this matters much, other than making us feel better about our temporary confinement. These changes, made permanent, still may not be enough to erase more than one hundred years of dumping carbon waste into the air.

COVID-19 made math a front-page exercise. We had to flatten the curve. But even when New York went on lockdown in late March, cases and hospitalizations continued to climb for two to three weeks. We saw math in action: between action and change there was a lag.

Climate change works this way, too. Changes we make now won’t immediately bring down the levels of Co2 in the atmosphere, or—really—even slow the growth, at least for now. Climate change follows similar math (exponential growth—look at the curves of COVID-19 before social distancing and the curves of Co2 growth in the atmosphere since 1900). The time scale on climate change is just much, much longer. We have less time–in a way—to take more drastic action, in pursuit of effects that won’t be felt for a decade or more.

It might be too late, even if we change our lives this much, and no one seems to think we’ll be capable of changing our lives this much for long. It’s August and social distancing is six months old. We’re tired of it. COVID-19 is racing back.

We aren’t even willing to change our lives this much—to socially distance, to avoid air travel—to save our lives now. Why would we be willing to sacrifice this much to save our future lives, or the lives of our future children?

There’s a white girl on the train, uptown D, long brown hair, drinking a green juice out of a metal straw. Omg are her shoes vegan leather? Wait… isn’t vegan leather just plastic? She has rings on all her fingers except her ring finger. I bet, in her Tinder profile, she describes herself as quote witchy unquote. She gets off at Columbus Circle. What’s her name, do you think?

I’m drinking my iced coffee with a plastic straw. I’m going to my boyfriend’s house. I look it up: Vegan leather is made from petroleum, which is made from oil. What do you think my name is?

I text Tommy, “I feel like u have the strongest will to live of anyone I know.”

Tommy texts back: “That is literally the best compliment I’ve ever been given in my whole life hands down.”

It’s not a joke though. My plan for climate change is suicide. It’s the same plan I have for if my lungs give out, cancer takes over, and every breath is a battle.

I’m not suicidal. I wouldn’t say I love living, but I love many living people, and I love my students, and I love writing. I want to stick around. But I don’t believe it’s somehow moral to suffer instead of dying.

My boyfriend’s grandma is dying of Alzheimer’s disease. “If I get like that, just kill me,” he says. “Please.”

Tommy texts, “It’s funny bc i often talk with Lauren Wilkinson about how when/if the apocalypse comes how we’d gladly walk into the zombie horde. But as she’s saying that I know she’s a wily bitch. She’d outlive everyone.”

I text back, “I could outlive everyone because of my survival training in youth. But I literally have no desire. Live for what? I wanna throw an orgy and do a cyanide pill.”

Saleema always tells me if the apocalypse comes, she wants to be on my team. “I have a car,” she says, “You get the passenger seat.”

Tommy texts, “Yeah but yr default is to fight. Which means we’re both going to be the final girls. All the while waxing poetic about being six feet under.”

“I agree,” I say, “but the thing is I would actively die. Fight to die in a way.”

“It’s reflexive, hoe. The kind of survival instinct I think we share. Honestly, I would rather die. But something trying to kill me unlocks this competitiveness that I didn’t know I had.”

“Lol yes same,” I type back. “If someone tries to kill me I’ll fight till the end. Nasty. Grab hair. Kick in Nards. I’m the only one who can kill me lol.”

“THAT’S EXACTLY WHAT IT IS. otherwise I wd be offended as fuck. If someone else killed me?”

“How dare they?”

This essay is a living will. I don’t want to live through an apocalypse, be it of my body or the planet. My grandfather got one thing right.

When it comes to the climate apocalypse that is someplace between possible and likely, kids would mean I couldn’t go. I wouldn’t do it. I wouldn’t leave them on their own. I wouldn’t raise kids knowing I’d throw my life away because the world was so painful, but expect them to keep on living.

I don’t know if I can make that promise—the promise to keep on living—to anyone.

NPR Headline: May 15 2019

U.S. Births Fell To a 32-Year Low in 2018; CDC Says Birthrate Is In Record Slump

“The birthrate is a barometer of despair,” said demographer Dowell Myers in NPR.

“Girl, true,” I say in response.

The NPR article discusses the economy, politics, but it doesn’t mention climate change once.

The PowerPoint slide says “Fitness” at the top. I’m not talking about cardio, y’all. Evolutionary biologists define fitness as the reproductive output of an individual.

It’s simple really, simple math. Let’s take… oh, I don’t know, rabbits. Let’s say one rabbit has ten babies and another has only one. That first rabbit has ten times the fitness of the latter, assuming all the babies survive. This is where you get into evolutionary strategies and game theory: If you only have one baby, you’d better make sure it lives. If you have ten, the investment in each can be a little less.

Sound brutal? This is how biologists imagine the survival of the fittest.

This last weekend, my boyfriend and I made a big and heavy meal together, and then he slept on me on the couch as I watched old episodes of Parks and Rec and scrolled through my Instagram. At around 2:00 am, he woke up, and I was ready for bed.

“Ready for bed babe?” I asked. He just nodded. We did that couple dance in the bathroom: He peed as I brushed my teeth, I peed as he brushed his, he washed his face, I took my night time pills.

In bed, with the lights off, I held onto him. And then his hand on my dick, and I was half asleep. “I’m tired babe,” I said. “You’ve already slept two hours.”

“Don’t worry, I’ll top.” And oh yes, oh this is what I wanted, and he was already hard, and the room was so dark I couldn’t see him anyway, and so I turned over on my stomach, the flesh of my own dick hard now too, and I felt him push inside of me, and I felt the room grow large and light and then large and dark again. He was using me to get off, and that got me off. I pushed the flesh of my thighs and ass back into his dick and he was deeper in me, all I needed then.

I turned over to see him, but the room was so dark I could only see his movement. “Are you gonna breed me?” I asked. “Use that hole,” and he did.

“Are you gonna breed me?” I asked, and I think he nodded, but I don’t know. What I do know is that two minutes later he pushed some half-cells inside me, and I held them in until the next morning, but eventually, yes, I did have to shit them out. How fit am I? How fit am I? He rolled over, and I came then too, and then, holding his body, we slept.

Here’s a good meme for you. It’s screen caps of that Greta Thunberg speech at the UN. She’s saying, “This is all wrong,” and “I shouldn’t be up here,” and “How dare you!” The caption at the top of the meme: “My sperm when I cum in another random guy’s ass on a Tuesday.”

In 1987 (Co2 levels 347.42ppmv), queer scholar Leo Bersani published an essay that became, over the next decade, a foundational text in the nascent field of queer theory. “Is the rectum a grave?” he asked, which, yes, but also, lol, why are queens so damn dramatic, I love us.

Bersani argues that the way gay people have sex ensures that our sex acts—unlike straight people’s—aren’t reproductive. No fitness for fags.

Most straight people imagine their legacy in the form of kids. That’s what they leave on this planet. This is my definition of futurity: Futurity is how I relate to what will exist on this planet when I’m gone.

Cumming in a rectum, then, ensures I won’t have kids. It’s a grave for the possibility of my genetic futurity.

As queer scholar Foucault put it just before dying of HIV, “The problem is not to discover in oneself the truth of one’s sex, but, rather, to use one’s sexuality henceforth to arrive at a multiplicity of relationships. And, no doubt, that’s the real reason why homosexuality is not a form of desire but something desirable.”

Being gay is good because it opens up the possibilities for different types of relationships as we live, not just children to remember us after we die.

But what if straights realized that their children might not have a future, either? That the fact of climate change may soon render us all queer? If there is no future, what do we do in the present? This is the possibility of climate change, one that we have not yet taken.

Goodbye capitalism, goodbye war, goodbye Defense Department and borders and surveillance and sorry World Bank, but bye to you, too. What we need now is a World Food Bank. Microsoft vs Apple, who fucking cares? The planet is melting. Can we build carbon sinks with biotic or abiotic components? That’s what I care about.

This type of radical departure from the status quo is the very thing, the only thing, that can save us now. By acknowledging that the earth is ending, we create the possibility of saving it.

Or will the straights (and certain gays) double down on zero-sum capitalism and be content with the deaths of everyone but the ones they made themselves?

Me? I’m sorry, Gramps. I don’t miss you. Your letter meant nothing to me, even then. What I didn’t know when you died: My rectum would become a grave. Even if I do have kids, I won’t be giving them your name. Even though I don’t know the stories, I bet dollars to donuts that you hit your son, my father, and your wife, and your second wife too. Yours is a story of addiction, which isn’t rare or troubling itself, and abuse, which isn’t rare, but troubles the waters of our family, still.

I don’t fault you for the way you died. I fault you for the way you lived. I want to live different, even if we all die the same.

Wanting to die when/if the apocalypse comes is indeed cowardly. It’s not lost on me that for many groups of people the apocalypse is already here, and has been for hundreds of years. And yet people lived through it, and continue to.

The indigenous apocalypse began hundreds of years ago. The Black American one, too. Queer people have been killed for countless years, often in silence, and a few decades ago and still now, they were murdered by state inaction in the face of a deadly virus.

Sound familiar?

White Americans have always tried to run away from the worst of our history. “Slavery was hundreds of years ago,” we say, “get over it!” We consume our way into wealth, we build economies based on endless growth on a finite planet.

And it’s the planet that’s now saying, “Enough!”

COVID-19 is showing us how unable we seem to be to care for the collective humanity we are a part of.

“Enough,” it’s our turn to say. Even if that means changing the way we live. And no, Mackenzie, using a metal straw with your green juice isn’t what I mean. Or wearing a mask in the grocery store. I’m talking about radically restructuring our cities, our nations, our states, to prioritize the planet, to limit the suffering of the most vulnerable to climate collapse, who also just happen to be the people upon whose suffering we’ve built our relative comfort.

The most at risk of dying from climate change are also the most at risk of dying from COVID-19: People without the infrastructure to protect themselves.

When can we pronounce all human life on the earth terminally ill? Only if we view humanity as an organism together, a family that sinks or swims together, will any of us have a real chance of survival—if not for ourselves then for the ones we say we love the most: our children.

An astute reader might find an odd and awfully heteronormative underpinning to the argument in this essay: One can have children without making new human beings. One can be an auntie or an uncle. One can, of course, adopt a child who’s already been born.

Adoption, yes. This might be the most ethical choice when it comes to our desire to parent in the Anthropocene. Even if I always did want biological babies, the image I had of myself pregnant is a relatively small thing to give up. In fact, this feels like a way to queer fatherhood, to imagine family without a direct biological link.

For me, though, adopting a child never felt possible. It’s just really fucking expensive. I always had an image of co-parenting with queer friends, and getting pregnant the old-fashioned way: with a turkey baster. I can’t afford tens of thousands in adoption fees. IVF? I don’t have the savings account. On top of the cost of actually, you know, raising a child.

I’m thirty-seven and a college professor.

For me, as a recovering working-class queer two years into a middle-class job, the ethical choice, adoption, is beyond my means. Like so many other ethical choices in late capitalism, only the very rich can afford it.

I text Ra’mon, who has two kids with their husband. They feel guilty for bringing new life into a melting world. And it’s not just the planet, but the politics of the moment, the rising white nationalism, the uptick in hate.

They feel guilty for having kids. I feel guilty for not having kids, for letting my parents die—unless I change my mind—without becoming grandparents, which they’ve always wanted.

Claire calls me to tell me she’s having a bébé. It’s 2020. It’s COVID time. I’m so proud of her. She’s so brave. Bringing a child into the world now. I could never. I don’t think I ever could.

“You won’t catch me having kids,” says Tommy, walking next to me on the Highline in summer. “Nope. My project is making sure I don’t die.”

I talk to Kelsey, who’s a straight married to a straight man I love, one of about four in the world. He has the Huntington’s disease allele. Huntington’s is a genetic form of dementia with very early onset—in your thirties. He watched his mom deteriorate from the disease as a kid, and kids can’t understand why their mom is suddenly angry, and then suddenly silent, and then suddenly sad.

“I never wanted kids,” she said, “but I was open.”

“Damon”—her partner—“did but only if he didn’t get the Huntington’s gene.” He did get the Huntington’s gene. “His grandfather shot himself when he got symptoms.”

“Honestly sometimes,” she tells me, “I feel inadequate as a cat parent.”

The slide says “The Carbon Cycle,” and I stare out at a bunch of twenty-year-olds and I tell them about the earth and, honest to god, I’m trying not to cry. Look. I didn’t make these children, but here they are. Here they are, looking to me to learn. Here they are, thinking I know something. Here they are, and here I stand looking at them, standing in front of a slide that says “The Carbon Cycle,” looking past them and out the window to an urban forest I can see in Washington Square Park.

“If urban forests aren’t going to fix enough carbon to make a dent in global warming,” I ask, “What can biologists do?”

These young people belong to me.

All young people are my young people.

I don’t have kids. I have Saleema and my boyfriend and Laila and Andrei and Kelsey and my parents and my sister and all the kids I’ve taught to care about the world, too. I might already be tethered. This earth, my earth, no clean way out. This earth, my planet, how I’d give my life for it, for them, for you.

All we can do is make the best of it. The good good news: nothing short of everything will save us now. Our children won’t save us now. We have to save us, for them.