For the fourth time in almost as many years, Ma Bille had to go in for eye surgery, this time to have her cataracts removed. She was not afraid: at sixty-eight years of age she had been in and out of the operating room so many times that the antiseptic reek of hospital walls was as familiar to her as the smell of baby poop. The thing that worried her, that made her wake up this morning with her heart hammering in her ears, was the suspicion that she was all alone in a world that had seen the best years of her life.

While she waited for sensation to return to her legs, she ran her mind over the tasks for the day. Her domestic routine, established after her husband’s death and perfected in the years since the last of her five children had left the house, was the cogwheel of her existence, the real reason to live. After the last operation she had shuffled around the house for five days with a blindfold of surgical gauze over her eyes, condemned to do nothing but eat, bathe, sit on the toilet bowl, and listen to the sounds of the street outside her window. She had emerged from that invalid’s limbo with a renewed zest for workaday duties, but since she noticed the fog creeping in again from the edges of her vision, she had begun to wonder if she was fighting fate.

At first, glaucoma—two failed operations, and one success. Now, cataracts, which, the doctors said, was a complication they had expected. Next time, God knows what else. She was tired of the hospital visits, of the countless eye tests, of the segments of her life that were stolen by anesthetics. But, especially, she was fed up with the troop of jeans-wearing surgeons who attended to her, who reassured her of complete recovery in happy-go-lucky tones, who declined to describe her ailment in comprehensible language and dismissed as inconsequential her complaints of blistering headaches, of the nausea that was triggered by the flash of bright lights, of the pain that seared her eyeballs night and day. After three operations, all that remained of the worst symptoms were the memories of how she had suffered. Now, quietly, without the theatrics of physical discomfort, her eyesight was fading.

The worst thing to happen to you, she said to herself, then dragged her legs to the side of the bed—huffing from the effort and wincing from the shocks of pain that shot through her knees—and edged them over.

She could feel herself slipping back into sleep, so she pulled aside the duvet and looked down at her legs. The sight of her stumpy, varicose, bunion-knuckled legs never failed to shock her, always seemed to mock her, to impose on her—at the start of each new day—an intimate image of decay. Mr. Bille used to say she had the finest legs in all of Ijoland, and sometimes, God forgive her, she thought it a good thing that he died before he could see what arthritis had done to her legs. The worst thing to happen to you, she said to herself, then dragged her legs to the side of the bed—huffing from the effort and wincing from the shocks of pain that shot through her knees—and edged them over.

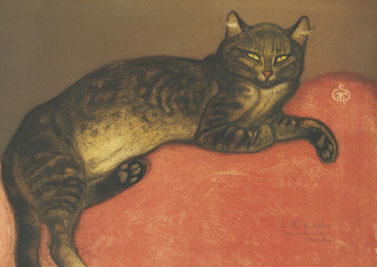

When she opened her bedroom door Cardinal Rex loped over to meet her with his tail raised. He rubbed his sides against her ankles, purring and flicking his tail; then he padded after her as she went about her housecleaning, shining his yellow-fever eyes at the back of her head and resting on his haunches to lick his charcoal fur whenever she stopped too long at a spot. After she wedged open the kitchen door and swallowed her morning dose of Celecoxib tablets and cod-liver oil capsules washed down with two bottles of lukewarm spring water, she scraped the leftovers of last night’s cooking into his green plastic plate. She sat on a shortlegged stool in the center of the courtyard and with a chewing stick cleaned her strong, yellowed teeth. While the morning air washed over her naked, collapsed breasts as she waited for the water on the stove to heat up for her breakfast and bath, Cardinal Rex ate at her feet.

She finished her meal of maize porridge, moin-moin, and Lipton tea, waited for the food to settle in her gut, then rose from the stool and carried her plates to the kitchen sink. Over the sound of running water she heard Cardinal Rex scramble up the fence of the house onto the roof to sun himself. She had lived in this house for thirty-two years, ever since Mr. Bille left her, and for many of those years she had cohabited with cats, yet she still wondered how come every one of the eight cats she had owned at different times always took the same path onto the roof. Her husband had hated cats—they were arrogant and disloyal, unlike dogs, he used to say. There was a time, when he was still alive, that she, too, favored dogs; but now the sight of their eager bodies, the sound of their yaps and bays and yelps and growls, gave her palpitations.

The first Cardinal Rex had been a white female cat. But after seeing the ease with which her coat got smudged, after suffering through the nighttime caterwauls of wooing males, and after what had to happen happened and she woke up one morning to find a litter of four blind kittens that their mother abandoned because she moved them from the rug in the parlor into a cardboard box lined with old handtowels, Ma Bille learned her lesson. When the animosity that bloomed between cat and owner drove the first Cardinal Rex into exile, Ma Bille replaced her with a black male cat. Until his death from stoning at the hands of some neighborhood children who mistook him for a witch’s cat, Cardinal Rex the second lived a happy, simple life. It was from his time that she established her routine of feeding her cats twice a day. It was with him that she fell into the habit of talking to her cats, of threatening to withhold their meals when their conduct called for rebuke, of rewarding them with scraps of dried crawfish when they were good.

Her plate washing done, Ma Bille took up the pot of hot water, shuffled to the bathroom, shouldered open the heavy-timbered door, and went in. The bathroom was small, low-ceilinged, and stank of mildew. A colony of chitinous creatures thrived in the wet earth underneath the metal bathtub. She glanced around out of habit to see if any cockroaches had ignored the daylight signal to return to their hiding places, but in the dim lighting, her eyesight failed her.

With her towel around her waist and her bare feet smearing the floor, Ma Bille emerged from the bathroom. The sun was blazing, the ground was awash with light, her eyes were suffused with the brilliance of everyday colors, and as she crossed the courtyard she stepped on something squishy. She halted in surprise, stooped to see better, released her breath in anger, then picked up the half-eaten rat by the scabby tail and tossed it over the fence. Raising her voice so that Cardinal Rex, wherever he was, would hear her, she said:

“No supper for you today, bad pussy!”

On ordinary days, after she took her bath she would slip into one of her old, wash-faded boubous and then walk to God’s Time Is Best supermarket on the street corner to buy a chilled bottle of Harp. She would return home with the beer, go into the kitchen to fetch her beer mug, then carry mug and bottle on a tray to the parlor and place the tray in the chair that stood before the window facing the street. That was where she sat, on the armrest of the chair, sipping her beer, gazing out on the tide of life through the age-browned, flower-patterned lace drapes, until lunchtime.

She rubbed palm kernel oil into her halo of thinning hair, cocoa-buttered her skin, drew on her going-out girdle and a white underwired brassiere. She chose her clothes with painstaking care…

But today was not an ordinary day. Ma Bille had somewhere to go.

She entered her fluorescent-lit room, stripped off the towel, and tossed it on the bed. She walked to her jumbled dresser and stared in the tall mirror, searching for soapsuds between her legs and mucus in the corners of her eyes. She rubbed palm kernel oil into her halo of thinning hair, cocoa-buttered her skin, drew on her going-out girdle and a white underwired brassiere. She chose her clothes with painstaking care, as she flitted from trunk to mirror and back again. She settled for a yellow brocade blouse and a George wrapper, and once dressed, powdered her face, applied mascara, glossed over the cracks in her lips with brown lipstick, and clasped on a coral-bead necklace and a matching bracelet. She wrapped some money in the knot of her wrapper, stepped into her rubber-soled Bata slippers, then walked to the front door and went out to buy her beer.

She was perched on the armrest, beer mug in hand, when the door of the house across the street crashed open. The house was fenced, but Ma Bille could see the front door through the grilled gate. She pressed her forehead against the window bars and watched as a figure emerged and sat down on the doorstep. She couldn’t make out the face—there was once a time when she could see all the way into the courtyard of that house—but she knew for certain it was Perpetua.

In all the years that they had stared into each other’s houses and watched one another grow old, Ma Bille and Perpetua had never called each other by name, never held a conversation, never greeted. Perpetua was a widow with only one child whom everybody knew was a drunk who hated her mother. To the scandal of her daughter’s condition was added other strangenesses: Perpetua never came out at night; she was the first person on the street to wall up her frontage and the only one who put razor wire in her fence, even though she was poor; she was the widow of one of the first foreign-educated men in Poteko, a man who had streets and government buildings in the city named after him, yet she was poor. Ma Bille had warned her children time and again—when they still lived with her—to avoid “that woman’s house,” and only her youngest, Nimi, disobeyed: he used to cross the street to sit and chat with Perpetua. Despite that provocation over the years the two women had not found an excuse to quarrel, but Ma Bille blamed Perpetua for the death of Cardinal Rex the second, because it was in front of her house that she had found his broken body.

Ma Bille turned away from the window, muttering with a vehemence that watered her eyes. She lifted her mug, tossed down the warm, bitter remains of her beer, and rose from her seat, carried the mug, empty bottle, and tray into the kitchen, then locked the kitchen door, her bedroom door, and the front door behind her. From her doorstep she scanned the sun-washed street. A FanYogo carton lay on the road, and strawberry yogurt had leaked out and pooled on her paved frontage, a lurid pink surface dive-bombed by flies. Ma Bille walked to the road’s edge, looked left, right, left again, and then hurried across. As she approached the other side she heard the murmur of Perpetua’s voice, and glanced in through her gate. Perpetua was chatting with a bread hawker, a young mother with a sleeping baby strapped to her back, who knelt beside her wooden tray piled high with oven-fresh bread. She was spreading mayonnaise on a split loaf with slow sweeps of her knife. Ma Bille stared. There was something different about Perpetua—she was wearing a new blouse, a striking shade of blue, like the sky on a bright day, today; and, also, she seemed to have lost weight, she looked younger. Then Ma Bille got it: she had shaved off her hair. At that instant Perpetua looked up and fell silent. The bread hawker turned around. “E kaaro, Ma,” she greeted, but Ma Bille walked off without answering, her footsteps quickening as Perpetua snickered.

It was close to Christmas, there were carnivals and street parties happening everywhere in the city, the roads were jammed with traffic, so the bus ride to her daughter’s house, which usually took twenty-five minutes, lasted more than an hour, and cost double the normal fare. When she protested the amount, the bus conductor called her an old soldier and barked at her to get off the bus and use her legs. He was shouted down by the other passengers, several of whom, all men, in response to his taunts, threatened to teach him a lesson they promised he would never forget.

The fourteen-seater Volkswagen bus was packed full. Ma Bille had taken the last spot, the seat beside the open door. The bus conductor leaned over her the entire ride, his shoulders jammed in the doorframe, his hip pressed against her side, his smell of old sweat and unwashed underwear blowing in her face. By the time her stop arrived her legs were shaking. “My lastborn is older than you, you stupid boy!” she hissed at the conductor as she disembarked, but the cornrowed, cashew-juice-tattooed teenager winked at her and whirled round to chase after the moving bus with long, easy strides. She shook her head after him, and then looked around for a respectable stranger to lead her across the busy motorway.

She gave him her farewell blessing only after he had promised to steer clear of civil rights marches, to abstain from drugs and alcohol, and, most important of all, to avoid relationships with crazy women, which all white women were.

Her last child was thirty-seven years old. He had lived with her until nine years ago, when he traveled to China—via Libya, then Qatar, then Malaysia—in search of a better life. He was married now, to a Filipino woman he had met in a textile plant in Zhengzhou, and they had two children, a four-year-old girl whom they had named Corazón after his wife’s mother, and a one-year-old boy who was called Ramón after his wife’s father. He had sent his mother their photographs with the last parcel of canned pork and imitation-leather handbags that arrived from him with climatic regularity. The letter that accompanied the parcel informed her he was doing well, that he no longer worked in factories but now tutored Chinese professionals in the English language, and that he might come to visit next year with his family. In her reply she had urged him to come quickly because the eye trouble had recurred, and she wanted to see her grandchildren before she went blind.

Nimi wasn’t the only one of her children who had made his home in a foreign land. Her first child, Ineba, lived in the UK, and had been resident there since she left Nigeria with her diplomat husband in 1982. She never sent money, gifts, or letters, and the last time Ma Bille spoke with her—four months ago, on her daughter Alaba’s phone—she had scolded her mother for her backwardness in refusing to get herself a mobile phone. Ineba had three children whom their grandmother had never met, and whenever Ma Bille expressed the hope that this oversight would be corrected, Ineba brushed aside her request with a litany of complaints about Nigeria. But Ma Bille expected to meet her first grandchild soon. He was a journalist and wrote for the Shetland Times, one of his articles had won a prize that his mother never tired of talking about, and she had told Ma Bille that he planned to visit Nigeria in the coming year to carry out research for the book he was writing about the immigrant experience.

Of all Ma Bille’s children, Otonye, her first son, was the first to leave home. He was granted a college athletics scholarship to the US when he was nineteen. She had felt he was too young to travel so far from home, and if he hadn’t insisted and threatened to run away, she would not have let him go. She gave him her farewell blessing only after he had promised to steer clear of civil rights marches, to abstain from drugs and alcohol, and, most important of all, to avoid relationships with crazy women, which all white women were. She didn’t know if he had kept his word, because the last time anyone in the family had heard from him was twenty-six years ago, when his mother received a Burger King postcard. It was postmarked Champaign, Illinois, and it announced in one short sentence that he had graduated magna cum laude. The script was in a hand that she recognized as her son’s, but the name was Tony Billie.

Her fourth child, Ibiso, lived in faraway, sun-ravaged Sokoto, where she was a home economics teacher in a mission school. She was married to Christ, as she curtly informed her mother whenever the issue of her single status cropped up in conversation. Ma Bille did not look forward to her visits, which happened once a year during the Ramadan season, because her born-again daughter dedicated her holidays to saving her mother’s soul.

Alaba, her third child, lived in the same city, Poteko, a few miles from her mother’s house. She was married to a Trinidadian, the tuba-voiced, hummus-complexioned Amos Stennet, who was a field engineer with Shell. He spent more time on floating rigs in the Bongo oilfields than he did with his family. Whenever he was onshore—as he was now, because of the spate of ransom kidnappings that had caused his company to evacuate all expatriate personnel to the mainland—he made up for the time away by impregnating his wife. Alaba, at forty-two, had seven children, four girls and three boys, the oldest in university, the youngest in kindergarten. Ma Bille doted on them.

The walk from the bus stop to the gate of her daughter’s house took seventeen minutes, and Ma Bille was puffing, her forehead dappled with sweat, when the gateman opened to her knock. Alaba lived in GRA—Government Reserved Area, a high-class neighborhood with middle-class antecedents—on a tree-lined street called Springfield Avenue. Her white-stuccoed, villa-style house stood amid a forest of cycads and conifers. The wall around the house was as high as a battleship and it was topped with strings of electrified wire. The winding, gravel-paved driveway that led to the front porch was bordered on both sides by manicured azalea bushes. When Ma Bille stepped onto the porch, the scent from the flowerpots that swung from the ceiling, that hung from the fluted pillars, that lined the floor and balustrade like squat terracotta sentinels with headdresses of vibrant color, made her sneeze.

“Welcome, Ma,” Alaba said. She spoke in a low, tired voice, and her face, underneath its bright makeup, was gloomy.

Ma Bille pressed the doorbell and waited for the housemaid to open for her. A key rattled in the lock, the steel-armored door inched open, and a face appeared. “Alaba!” Ma Bille exclaimed, throwing up her arms.

“Welcome, Ma,” Alaba said. She spoke in a low, tired voice, and her face, underneath its bright makeup, was gloomy. She wore a red silk blouse and tight blue jeans. Her nubuck leather waist belt—which was studded with mother-of-pearl, as were her red thong sandals—cinched her blouse over her belly. Her gold-streaked braids were gathered in a ponytail, her fingers and toes were garish with blue nail polish, and around her neck hung a gold necklace dangling a heart-shaped ruby in the cleave of her breasts. As she pushed the door wide and stepped aside for her mother to pass, a blast of eau de cologne wafted through the doorway.

“Where’s Tokini? Why are you not at the boutique? What happened?” Ma Bille asked in a rush, and peered into her daughter’s face. Alaba did not reply until the door closed.

“It’s a long story.”

Ma Bille followed her daughter into the high-ceilinged lounge, then sat down in the white leather armchair closest to the French window and jiggled her knees while Alaba headed to the kitchen to fetch some drinking water. As Ma Bille drank, she kept her eyes on Alaba’s face, but her gaze clouded over when the cold water stuck in her throat. She choked and spluttered, and beat her chest with her hand. She took a deep breath, ducked her head, and dabbed her eyes with the edge of her wrapper, then straightened and set down the glass.

“Tell me before I die of fear. What has happened?”

With an impassive voice, Alaba said that the housemaid had been dismissed.

“Why?” Ma Bille asked.

“I found out she was pregnant.”

“What!”

“I’ve suspected it for some time, she’s been acting funny. But when she was cleaning fish two nights ago she threw up in the kitchen, so I confronted her.”

“But how, who… no!”

“Yes, Ma, it was him.”

“Ah! Amos has killed me! Where is he? Let me talk to him!”

“I kicked him out with Tokini. He must fix that problem before he sets foot in this house again. When a man can’t keep it in his pants, this is the disgrace.”

“But, Alaba, the kidnappers…”

“Serves him right if they get him,” Alaba said. “Good riddance to bad rubbish.”

“Don’t say that. Don’t say something you’ll regret later. What he did was wrong, but he’s still your husband. Call him. Let him come back. Let’s look for a way to solve this.”

Alaba’s eyes glistened, her nostrils flared, her lips curled in a snarl, she gripped her knees and leaned forward. “No, no, no, Ma, hundred times no! After seven children, what more does that man want from me? I’ve not even told you—I’m pregnant again. The few months he’s spent at home, he’s impregnated me and the house girl together! So all the time he’s away, what has he been doing? How many of his bastards are running around the streets?”

Ma Bille shifted her feet and rubbed her palms together. After a long pause, she said: “Please, my daughter, treat this with wisdom. You know what I always say: the worst thing to happen to you—”

Alaba cut her off. “Yes, Ma. I know what you always say.”

They relapsed into silence. The house was alive with electronic noises: the whirr and screak of the ceiling fan, the hum of the refrigerator, the sporadic clicking of the stabilizer; but it was the faraway, persistent woofing of a dog that broke into Ma Bille’s thoughts. She cocked her head, listening to the sound. Her blunt-nailed, wizened hands twitched in her lap.

“You’re thinking about them, aren’t you?”

Ma Bille looked up to find her daughter staring at her; the expression on Alaba’s face was hidden by the fog that followed Ma Bille’s gaze like a willful shadow.

“Yes,” Ma Bille replied.

“They were just dogs.” Alaba leaned forward, so her face jumped into focus. “It was a long time ago, you should forget it. There are more important things to worry about.”

“Alaba,” Ma Bille said, holding her daughter’s gaze, “one day you will see that the only important things in this life are your memories. So leave me with my own.”

“All right,” Alaba said. She folded her arms across her belly and pursed her lips, then changed the subject. “So why did you come? You know I’m at the boutique around this time.”

“I wanted to see Amos. I was planning to wait around till you returned.”

“I hope no problem?”

“My operation is tomorrow.”

“Hah, I forgot. This eye problem even, it’s getting too much. This is the third time, isn’t it? I hope you’re not afraid?”

“He just disappeared in America like a person who has no background.”

“No—fourth time,” Ma Bille said. “I’m not afraid. But I need someone to follow me to the hospital. I was hoping it would be Amos, but with this thing he has done, it will have to be you.” The barking had ceased. From the treetops outside, birds twittered. Ma Bille spoke. “All other times I’ve gone alone, so you know I wouldn’t ask if it wasn’t important. The nurses these days are not very nice, and they’re overworked anyway. It’s not that I can’t go by myself, but they’ll bandage my eyes, so I won’t see. The last time after the operation I woke up at night with a running stomach, and I stayed in that hospital bed calling for more than an hour, yet nobody came. I had to crawl out of the ward on my knees, because I kept banging my legs against the beds.”

“I’m sorry, Ma. I didn’t know it was like that.”

“It’s okay,” Ma Bille said. “Old age has its lessons too.”

“But it’s not okay!” Alaba burst out. Ma Bille stared at her in surprise, and kept on staring as Alaba shot out of the chair and paced the room, her braids swinging, her hands chopping the air, the slate-flat heels of her thong sandals slapping the terrazzo. “I mean, what will people say when they hear that my mother crawled on the hospital floor, a public hospital for that matter? That is the height of suffering—and yet you have children who can afford to send you abroad for treatment! But where is Otonye, ehn, where is that one? He just disappeared in America like a person who has no background. And see Ineba, with her fri-fri talk, like it is British accent we will eat. As for Nimi, he’s the youngest, he should be here taking care of you instead of sending all those fake Chinese bags that anybody can buy in bend-down market!”

“Alaba… ”

“No, Ma, I have to tell you my mind. It’s not fair! All of them are abroad enjoying their lives, but look at me, look at my life, look at what Amos has done to me. I can’t be the only one doing everything. Taking care of my children, taking care of my husband, taking care of my mother, going to my boutique every day because all those girls I hired are thieves! I have seven children, plus another one coming, and now Amos has gone to give my house girl belleh! Nobody can take me for granted! I’m not a donkey that will be carrying everybody’s—”

Ma Bille raised her hand. “Sit down, Alaba. You’re giving me a headache.”

Ma Bille raised her eyes, stared at her daughter’s face, searching its contours for traces of the child she had breastfed, whose nose she had sucked mucus from, whose mouth had opened wide to gulp food from her fingers.

Alaba strode to the seat opposite Ma Bille and dropped into it. She crossed her leg, clutched the arms of the chair like it was hurtling through the air, and stared into space, scowling.

“Everybody has their own life to live,” Ma Bille said quietly.

“I don’t expect anybody to come and take care of me. I don’t ask any of you to feed me. All I’m asking is that you follow me to the hospital for my operation tomorrow.”

“But I can’t, don’t you see?” Alaba said. She stretched her hands, palms open, toward her mother. “I have to be in the house when the driver brings the children from school. I can’t leave them alone, I have to cook for them. If Tokini was still around then I would have followed you, no problem, but I can’t, not now, not until I get a new house girl.”

Ma Bille opened her mouth to speak, but shut it without making a sound. She bowed her head, stared into her lap, struggled to compose her face. One word rose above the hubbub in her head—abandonment. Her husband, her youth, her health, her sight even: all had abandoned her. Her children, too, had abandoned her. All the years she had given, the sacrifices, the worrying, the love—everything she gave, she gave for nothing.

“No, not for nothing,” she murmured. “I gave because I wanted to.”

Alaba glanced at her. “What did you say, Ma? I didn’t catch that.”

Ma Bille raised her eyes, stared at her daughter’s face, searching its contours for traces of the child she had breastfed, whose nose she had sucked mucus from, whose mouth had opened wide to gulp food from her fingers. Memories shuffled through her head, blinding her with images. When that face was seven years old, the child had tripped over a broom and gashed her forehead against the dining table, right there, where that scar glistened beneath the face powder. At seventeen, she had come first in her class, and as a treat Ma Bille took her to the Chinese restaurant that used to be on the third floor of Chanrai House. When she was in her final year in university—she was twenty-three then—Ma Bille sold her finest pieces of gold jewelry, presents from her late husband, to the black-market merchants on Adaka Boro Street, to pay Alaba’s fees. That night, when Alaba came home from the hostel to collect the money, she hugged Ma Bille and whispered against her cheek, “I love you, Ma.”

I love you too, Alaba, Ma Bille thought, gazing at her daughter’s averted face. All the support she had given, and she still gave, accompanying her daughter to the hospital whenever she went into labor, bathing her grandchildren when they were babies, feeding them, rocking them to sleep, passing on to her daughter the tricks of child-caring—everything she gave, she gave because she wanted to.

Ma Bille said her daughter’s name.

“Yes?” Alaba answered in a sullen tone, and sneaked a look at her mother.

“That belt you’re wearing, it’s too tight. Go and remove it. It’s not good for the baby.”

The children were happy to see their grandmother. Every time Ma Bille responded to the greedy questions they shot at her—all six of them who had tumbled into the house in a storm of dust and noise—she said their names: Wariso, Sekibo, Owanari, Nimi (whom everyone except her called Small Nimi), Ibinabo, and Dein. The oldest of Alaba’s children, Enefaa, who was studying for a law degree at the University of Jos, was Ma Bille’s namesake. Amos had insisted that his children be given native names, and Ma Bille, whenever she had the chance, instructed her son-in-law on the pronunciations, explained the meanings, described the idiomatic treasures of his children’s names.

It was evening when Ma Bille stood up to leave. The driver had closed for the day and Alaba was too busy with the children to drive her mother home, but it didn’t matter, because Ma Bille said she wanted to walk to the bus stop. The exercise was good for her legs, she told her daughter.

Six-year-old Ibinabo escorted her from the house, singing in a breathless voice and skipping circles around her grandmother. Her smooth legs flashed; her bare feet scattered gravel on the path. The gateman emerged from his cubicle, pulled open the gate, and Ibinabo crooned her goodbye, then whirled round and raced up the driveway toward the house. Ma Bille passed through the gateway and headed down the road she had come, her footsteps dragging. The road ahead was empty, darkened by twilight, bleak. As Ma Bille approached the fence of the next compound she heard a strange noise behind her, turned around to look, and froze.

A dog stood before her, near enough that she could smell its earthy odor. It was a big one, an outsized beast: its thick legs were splayed under the weight of its trunk. Its short-haired coat was brindled, brown and black, and a ruff of spiky fur grew over its shoulder and down the curve of its spine. A studded collar was fastened around its neck, and the leather leash snaked between its legs. It grinned at Ma Bille, its tongue lolling, its tail stump twitching.

“Don’t worry—don’t be afraid.” The speaker, a blond, teenaged girl, approached Ma Bille at a saunter. She was panting. “Here, Granbull, here, boy—woohoo!” she said to the dog, and stooped to pick up the leash. “Let’s leave the nice lady alone.”

When she tugged the leash, the dog opened its mouth and let out a boom. Then another, and another, each bark deeper, more ferocious. It resisted the girl’s desperate pulling without taking its heavy-lidded eyes off Ma Bille. Its red, serrated lips flapped and quivered.

“Behave, Granbull!” the girl commanded. She threw Ma Bille a close-lipped smile. “He’s never acted this way before. Maybe he knows you?”

“No, it’s not that,” Ma Bille said. “I have the blood of five dogs on my hands.”

The dog was still barking, its snout flecked with foam, and the girl was staring, her eyes round with shock, when Ma Bille turned and walked away.

In the struggle to free themselves the dogs had entangled their chains, and they were bunched together in one corner of the verandah, where the floor was puddled with dog-hair-colored water and scattered with dogshit.

She remembered their names, all five of them. “One for you to name and look after,” her husband had said to each of the children every time he brought home a round-bellied Alsatian puppy. It was Ineba who started the trend in beverages. She was gifted the first dog, and she named it Whiskey after her father’s favorite drink. Three months later, when Otonye got his dog, he told his sister, “Now Whiskey has her Brandy.”

Alaba called hers Sherry, because, she said, the name sounded aristocratic. Ibiso, even then, had faith only in what she knew, so she called her dog Cocoa. Nimi chose Coffee, because Beer or Tea or Coke did not sound to him like names even a dog would bear.

The dogs, all five of them, died on the same day thirty-six years ago, on a hot July afternoon. Because the sun was out and it was a public holiday, Ma Bille had instructed the children to wash the animals. After the bath, the dogs were tethered to the verandah railing so that they would not roll in the yard and soil their wet coats. Ma Bille was in the parlor darning school uniforms and listening to Boma Erekosima on FM radio when Nimi entered in tears and told her Coffee was suffering. She went outside to see for herself what the matter was. In the struggle to free themselves the dogs had entangled their chains, and they were bunched together in one corner of the verandah, where the floor was puddled with dog-hair-colored water and scattered with dogshit. The dogs whined and yowled, strained against their chains, looked dejected. They were plagued by a buzzing swarm of flies. Ma Bille directed the children to unravel the chains and clean up the mess, but even after the floor was washed with Izal disinfectant, the flies remained. The dogs shook themselves fiercely, and snapped at the air, and ducked their heads, but the flies circled and swooped, tormenting them. In a final exasperated effort Ma Bille fetched the can of Baygon insecticide from her bedroom and sprayed the floor, the walls, the flies, the dogs. The flies dropped out of the air, the dogs lay down in relief, Nimi wiped his tears, and Ma Bille went back inside to catch her radio program. Ten minutes later the dogs began to howl, and they did not cease this racket until they were stretched out in all corners of the yard, their coats sodden with diarrhea and blood and vomit, their jaws locked in the snarl of death.

“I don’t beg anybody for friendship,” she said, her voice assured, careful with pronunciation.

It was the worst time of her life: the guilt, the grief, the pileup of disasters. Two days later, two days after she killed the dogs, Mr. Bille suffered the final heart attack. There had been no time for forgiveness, no time to coax him out of the silence that followed his explosion of rage at the news of the dogs’ deaths. One morning he rose and left for work without replying to her greeting or eating her food, and by evening he was dead.

But for her children, she would not have survived. The catastrophe that collapsed her world exposed her children’s toughness. They stood by her in her darkest hour, frightened out of their mourning by the intensity of hers, pleading, consoling, urging restraint as she rolled around in bed and beat her fists, as she retched when the tears would no longer seep from her stinging eyes, as she wallowed in guilt and snot, embraced her grief along with her pillows, and turned her back on life, hope, self-control. Her children fought her with common sense and coerced her with love. They reminded her of the times the doctors had warned their father to give up smoking and alcohol and to adjust his eating habits; they told her, the dogs’ deaths don’t matter, the dogs’ deaths don’t matter, the dogs’ deaths don’t matter, until, one day, the dogs’ deaths didn’t matter. The worst thing that happened to her revealed the best thing she had.

When Ma Bille turned into her street, the security lamps on the front walls of the queued houses were glinting dully in the dusk. She stopped opposite her house, looked left, right, left again, then placed her foot on the road and looked right, just in time to glimpse a shape streaking across her frontage. Cardinal Rex, wherever he’d been, had seen her, she thought.

“That was a rat. They’re getting bigger and bigger these days.”

Ma Bille spun around, wincing as her joints creaked. But when her eyes—squinting, straining in the gathering darkness—confirmed what her ears had heard, she forgot about her pain. It was Perpetua.

Her gate hung open, which, given the lateness, was unusual; and, even stranger, Perpetua was still sitting in the darkened doorway of her house, as if she hadn’t moved since morning. Ma Bille sniffed loudly to mask her amazement, and slowly, deliberately, turned away. She hurried across the road, unlocked her front door, then stood on her doorstep, one leg in and one leg out, stared into the darkness, the loneliness of her house. She pulled the door shut and walked back across the road. She entered Perpetua’s gate, halted in front of her, and said, “How come it’s today you’re talking to me, after all these years?”

Perpetua raised her hand to slap away a cloud of mosquitoes. “I don’t beg anybody for friendship,” she said, her voice assured, careful with pronunciation.

There seemed nothing left to say, and Ma Bille’s legs ached. “I should go,” Ma Bille said.

“I know—time to feed your cat.”

“Yes.”

Ma Bille did not move. She wondered if she should ask. It wasn’t her business, but Perpetua had reached out, broken the silence. For a reason.

In a cautious tone, Ma Bille asked, “Is there a problem?”

“No,” Perpetua said.

“Are you sure? I’ve never seen you outside this late before.”

“Yes, I’m sure,” Perpetua said. “It’s just that my legs have refused to work.”

“Ah.”

Ma Bille clicked her teeth together. “Sorry, I know the feeling. My legs do the same thing every morning.” She paused. “Should I help you inside?”

“I’ll be grateful,” Perpetua said.

Ma Bille started forward, and Perpetua leaned aside to let her pass through the doorway, then raised her arms so that Ma Bille could grasp her by the armpits. Ma Bille pulled up the smaller woman, clasped her to her chest, and then dragged her into the house with backward steps. After a drawn-out, exhausting effort, Ma Bille eased Perpetua into a chair in the parlor, and then dropped into the adjoining seat, blowing hard and dabbing her face with the edge of her wrapper, her free hand rubbing her shaking knee.

When her heart rate calmed, Ma Bille pushed herself to her feet. Perpetua’s house was the same floor plan as hers, and in the dark, she could have been at home. She walked to the window and drew the curtains closed, then felt along the wall for the light switch and snapped it on. Perpetua was sprawled in the armchair, her arms dangling over the sides and her legs stretched out before her. Her ankles were swollen to the size of her calves.

“How are your legs?” Ma Bille asked.

“Still dead.” Perpetua passed a hand over her short dapple-gray hair. “It’s my arthritis. I’ll have to find a way to get to the hospital tomorrow.”

“Which one?”

“College Hospital.”

Ma Bille walked to the open door and gazed out for long seconds, then turned back into the room. “I’m going to College Hospital tomorrow for my eye operation,” she said. “In the morning, around ten… ” In the warm light, she caught the gleam of Perpetua’s teeth. She smiled back. “The blind leading the lame, no?”

At Ma Bille’s words, Perpetua looked down at her legs, the set of her head as expressive as a sigh.

“Don’t worry, it will be okay, these things happen for a reason,” Ma Bille said. “As I always say: the worst thing to happen to you is for the best—”

“Sometimes,” the two old women said together, and stared at each other in surprise, then burst out laughing, their voices ringing through the house and across the street.

A. Igoni Barrett was born in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, in 1979 and lives in Lagos. He won the 2005 BBC World Service short story competition, and his short fiction has appeared in Kwani?, Guernica, Black Renaissance Noire, and AGNI. This story is from Barrett’s short collection, Love Is Power, or Something Like That (Graywolf, May, 2013).