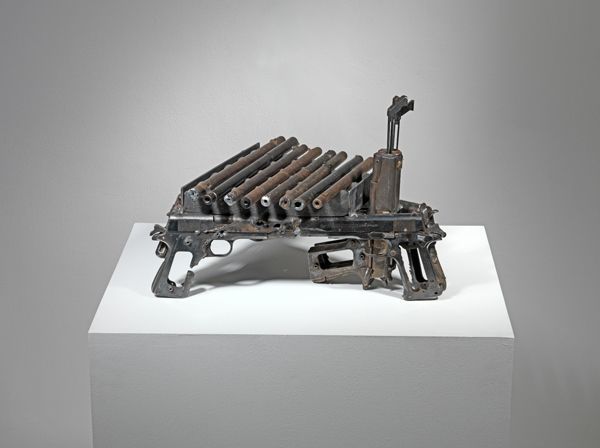

© the artist; Courtesy, Lisson Gallery, London

How We Won the War

Once again we received orders to occupy a madhouse, because the nutcases kept shooting at us. Right away we began shooting back like mad. The fire only died down the next day. One nutcase stepped out of the building with his hands up and said, “I’m not crazy. I’m a time traveler. I was sent to sign a peace treaty with you.” We reported on the two-way radio that the only nut alive asked to surrender, but that we shot him anyway, so that the entire future can know. In his coat pocket we found a newspaper clipping from the twenty-third century with a headline announcing the end of war. The headline faded in front of our eyes. We wasted no time, and immediately stormed the next madhouse.

How to Dance

“Let’s dance, Death,” said the little girl.

“I never learned how,” Death admitted.

“If you give me your hand,” the girl offered, “I can teach you.”

“I don’t think we have enough time,” Death pointed out. “The missile is about to hit.”

“Give me your hand anyway,” asked the girl. “I’m afraid to dance alone.”

Circle

I tried to write at the café again, but couldn’t concentrate because I kept waiting for the next siren. A gray-haired man at a nearby table said, “I can’t believe my children are going to stay here. This can’t go on any longer.” His friend asked, “Then why don’t you just leave yourself?” The man shrugged and said, “Because of my parents.”

Outside of Time

In the room with the grief-drawn shutters, outside of the rain, she makes her son’s bed. Time stands still. She’ll dream him back from the dead.

The Very Short Legend on the Disappearance of Birds

This was a kingdom where sirens were heard every minute of every day. But one night—otherwise this wouldn’t be a legend—the alarm system in the entire kingdom broke down and wouldn’t play. All the kingdom’s citizens woke up in a cold sweat right away. The silence was grand and terrible decay. It was as if the worst had come their way: the current war ended before the next was underway. To everyone’s relief, the malfunction was fixed before sunrise. The few birds that remained in the kingdom crashed into the windows of skyscrapers in the capital.

The Interpretation of Reality, As Explained to Me by a Five-Year-Old

—Is there a bomb shelter in dreams, too?

—Why do you ask?

—Because I dreamt there was a siren. And I didn’t know where to run.

—So what did you do?

—I woke up.

Boris Anatoliwitz Epstein’s Muse

By the way, in 1945 World War II ended. Oh well. And my paternal grandfather’s uncle—Boris Anatoliwitz Epstein—to keep this short I’ll try to call him Seryoja from here on out—completed the great endeavor he’d begun long before the Nazis killed his momentum: a Yiddish translation of the Odyssey (from Russian). It almost goes without saying that he couldn’t help himself from inserting into the story, among other things, a bald guy who fought with him in Stalingrad: the man boasted about killing three German cyclops with one potato. And in his version, Odysseus woke up on the beach in Calypso’s arms and said: “Spit on my chest. I like the sea.” And of course, each time a sailor watered down wine, he announced: “Red wine is good for your health and you need your health to drink vodka.” Etc, etc. The whole thing wasn’t all that well received by his one-and-only reader (his wife, Masha Arkadyevna Epstein, who, in short, I will from now on call Natasha), but Boris Anatoliwitz Epstein dismissed her objections immediately: “Just wait till I start translating Don Quixote,” he said. She hit him over the head with a frying pan. She was his muse, but that’s really another story.

The Addiction to Happiness

There once was a man who replaced the names of all the contacts in his phone with the name of the woman who left him. Since then, whenever the phone rang, if only for a moment, he was as happy as a child.

Alex Epstein was born in Leningrad (St. Petersburg) in 1971 and moved to Israel when he was eight. He is the author of ten works of fiction in Hebrew, and in 2003 was awarded the Israeli Prime Minister’s Prize for Literature. His work has appeared in Guernica, Iowa Review, Electric Literature, Words Without Borders, Kenyon Review, PEN America, and elsewhere. He lives in Tel Aviv. Two of his collections of micro-fiction, Blue Has No South and Lunar Savings Time, are available in English from Clockroot Books.

Yardenne Greenspan is a writer and translator working in Ithaca, New York. She has an MFA in fiction and translation from Columbia University. In 2011 she received the American Literary Translators’ Association Fellowship. Her translation of Some Day, by Shemi Zarhin, was chosen for World Literature Today’s 2013 list of notable translations. Yardenne serves as Asymptote Journal’s editor-at-large for Israeli literature. Her translations from Hebrew include work by Gon Ben Ari, Etgar Keret, Yirmi Pinkus, Alex Epstein, and Yaakov Shabtai. Her fiction, essays, and translations have been published in The New Yorker, Haaretz, Words Without Borders, Drunken Boat, World Literature Today, Hot Metal Bridge, Two Lines, and Asymptote, among other publications. She is currently working on a novel about fatherhood and the American-Israeli dream.