Carl had a secret thought about his boss, Ray. Ray had a secret thought about Lisa, one of the girls in fundraising. Lisa had no thoughts about Ray, secret or otherwise. At least that’s what she would have said if anyone asked her.

And who would ask her? Ray just wasn’t the kind of guy a girl like Lisa would think about. He was old for one thing—she put him at 35, minimum—with the slumped shoulders and jutting forehead of a Neanderthal, Also, he was short and prone to V-neck sweaters in cheap synthetic blends. If, for some reason, his name had come up in conversation, she would have said something like, “Ray? You mean Ray the computer guy?” as though she knew a number of Rays and couldn’t quite place him.

In fact, Lisa knew exactly who Ray was: she had inadvertently been the cause of a long-running joke about him. Once, at an office party, Ray had gotten drunk and stared so closely at Lisa’s cleavage that his face practically touched the scoop of her scoop-neck bodysuit. In the bathroom afterward, when Lisa recounted the incident to a handful of co-workers, Lauren had wrinkled her nose and exclaimed, “Eeew! A booby gazer!”

After that, whenever the database went down or the printer wouldn’t work one of them would say, “Better call Booby Gazer,” and they would throw their heads back and laugh. They always pronounced it in the Boston way: “Booby Gayzah,” although none of them actually spoke like that. Over time, the nickname had morphed, first into “Bobby Gayzah,” then, after a number of months, into simply, “Bobby.”

“Why does everyone call me Bobby?” Ray asked one day. He was standing in the hallway, looking back at them with the meek, bemused expression Lisa had sometimes seen on her father’s face when she and her sisters mocked him. She felt sorry then and a little ashamed, and she pretended to be busy with a file on her desk while Lauren said, in a bright, false voice, “That’s not your name?”

These two incidents were the exception, though; most days Ray never crossed Lisa’s mind. So it was a surprise one morning when she woke up to find that she’d dreamed about him.

In the dream, Ray had a daughter. That was it, that was the whole dream: the fact of the daughter (she was about five or six years old), and a sweet, floating sense of joy—Ray’s joy—for he had been beside himself with happiness.

He was married, he had two children; there was no way she’d go down that path.

“Yeah, right,” Lisa said out loud, throwing off the covers. The floor was cold under her feet but the air was warm, an early summer sensation. She stopped to stretch, naked, in front of the mirror and her breasts rose up a little, nipples erect. She stood there a moment on the cool floor, transfixed by the perfect wholeness of her reflected body. A nameless anticipation was blossoming inside her. The dullness, the shrinking withdrawal of the winter months, was over; she felt dilated and alive, like a flower turning to meet the sun.

Out of nowhere she thought of the VP of fundraising, the corded muscles of his forearms when he rolled up his sleeves. Not that this meant anything. He was married, he had two children; there was no way she’d go down that path. The thought was just an extension of the physical happiness she felt right then, of the heightened sense of perception that brought to her, as she dropped her arms and walked into the bathroom, the memory of his smell—sharp and slightly sour beneath the starch of his shirt.

Lisa had no intention of mentioning her dream to Ray. Why on earth would she? It was weird enough that she’d dreamed it. Later that day, though, when she saw him sit down alone at the other end of the office lunchroom, she heard herself call out, “Hey, Ray, I dreamt you had a daughter.”

Ray looked up from his sub. “A daughter?” he said, his face oddly empty of expression. “Really?”

“Yeah,” Lisa said carelessly, “a little girl, like about five years old.”

Ray tipped his head. “A daughter,” he said. A quizzical, wondering look came into his eyes.

Then Ray’s assistant Carl lumbered in with a slice of pizza on a paper plate and Ray’s expression darkened. “You better not be coming in here if that server’s not backed up,” he said.

Carl bent his head like a balky ox. “I’m not,” he muttered.

Ray glanced at Lisa and snorted. “What do you mean you’re not? You’re not in here?”

“Th-th-the backup’s already f-finished.” Carl’s face had turned the dark red of an internal organ.

Lisa stabbed a piece of lettuce with her fork. Why do that? Why make the guy stutter? So Carl was a weirdo—that was still no reason to humiliate him. Ray really was a dick; she was sorry now she’d bothered to say anything to him. She took a few more bites of her salad and read another paragraph in her magazine, just to show that she had nothing to do with either of them. Then she closed the lid of the plastic container, tucked the magazine under her arm and walked out of the room.

She was aware, without actually thinking about it, of the figure she cut from behind: the curve of her skirt, (her butt was one of her best features), the swing of her long, dark hair. It was not that Ray and Carl were men she wanted to attract; it was just a habit, like checking the rearview mirror in the car. She was used to being noticed and she dressed for it.

Down the hall in the kitchen, she dumped out the remains of her salad and put her fork and glass in the sink. Someone, or maybe several people, had left their dirty dishes: a few mugs, a plate, a glass filled with used silverware. Lisa squirted soap on the sponge and slowly, without resentment, began to wash them.

At the beginning, when she was thirteen and just developing, being stared at had humiliated her. Men seemed to watch her everywhere—when she bought a slushie at the convenience store, when she waited at the bus stop. She would feel it before she saw it: the tensing of the air, the sudden, blood-freezing isolation of being marked out. Then a hot shame would claim her body and she would hunch her shoulders and hurry by. No one ever helped her. When it happened once at the post office, her mother just turned away, a rigid half-smile on her lips, and asked for two books of stamps.

Over time, this fear and confusion had subsided. Being attractive became just a part of Lisa’s sense of herself, something she could flaunt (in a white halter top and mini) or pretend to disregard (sweatshirt and baseball hat). This public Lisa was her, but also was not; she held it out at a little distance from herself, like one of those old Venetian masks.

It was a relief, at times like this, to forget all that, to just let the sound of the running water, the warm sun from the kitchen window, lull her into silence. An animal silence, without any need to think or react or monitor, the clamoring, unruly thing she knew as herself suspended, bat-like, in a corner.

She laid a clean paper towel on the counter and then, with a simple sense of pleasure, placed on it the clean forks and spoons, the mugs and glass, the plate.

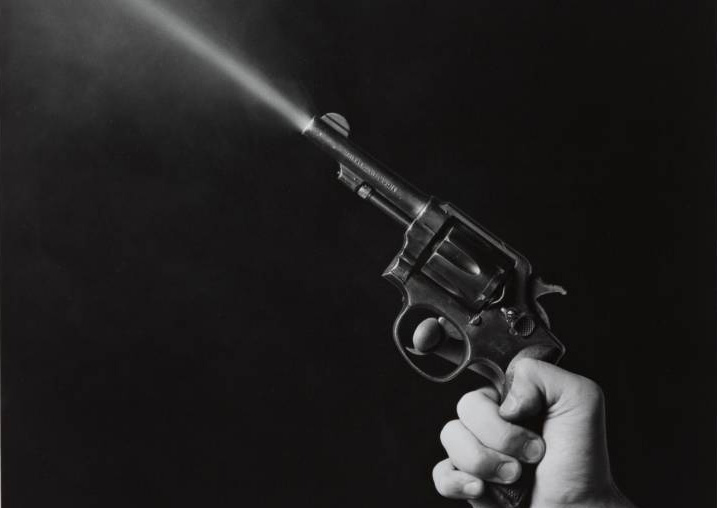

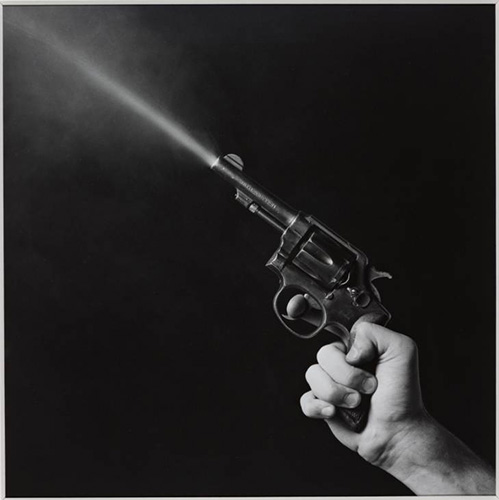

That night Carl woke in a sweat, his blood pounding. He sat up and reached into the drawer of his bedside table, crawling his thick fingers past the magazines until they made contact with cold steel of his grandfather’s gun. The red numbers on the clock read 4:08. He pulled his hand back and lay down again. Go to sleep, he told himself, but it was too late, he was already thinking about Ray.

He would come and stand in the doorway and say that, loud enough for everyone on the hall to hear: Carl, Carl, Carl.

What do you mean you’re not? You’re not in here? And then stupid him, stuttering like an idiot in front of that hot girl from the fundraising department. Lisa, her name was. They were all like that in fundraising, stalking around in their high boots, swishing their hair. They didn’t give Carl the time of day. Or Ray either, for that matter. For a second, this thought eased the tightness in Carl’s chest. But then he started thinking of other things Ray had said, days and weeks and months of things. You didn’t know that, Carl? You haven’t finished that, Carl? Carl, Carl, Carl. He would come and stand in the doorway and say that, loud enough for everyone on the hall to hear: Carl, Carl, Carl. A sort of joke it was supposed to be, one guy ribbing another. No one but Carl seemed to see the hard edge of contempt in Ray’s eyes.

During the day, when they happened, Carl’s impression of these things was muffled and oblique, as though he were listening through a heavy scarf. Even the adrenaline that surged through him at those moments had a distant, barely-felt quality. One or two nights a week, though, Carl would lurch out of sleep, his body tense with fury. Then it all would come back to him with searing precision, and he would lie awake reliving every insult.

The gun added a new dimension. Carl had acquired it accidentally a few months earlier, at the estate sale at his grandfather’s house. The morning before the sale, everyone in the family had gone to the house to pick something out for themselves. They were given colored stickers and told to tag whatever they wanted. Carl chose his grandfather’s bedroom set. This hadn’t seemed strange to him; he’d just moved to a new apartment and he needed a bed. The matching bedside tables and dresser were an afterthought: they all went together, so it seemed like a smart decision to tag them, too. But his father had made a big deal out of it afterward with his uncles. What kind of a douchebag would ask for a dresser when he could get a rifle or a table saw? Carl’s father looked around at his brothers as he spoke, the laughter already beginning to shake in his loose, red cheeks. He turned one hand palm up, as if to say, “Are you with me or what?”

They were, of course. Or so Carl assumed. He kept his face averted, so he never actually saw who had joined in and who hadn’t.

It was only after he got home that he found the gun, as he was idly pulling open the drawers on one of the side tables. It was in the top drawer, wedged behind a piece of cardboard that made a false back a few inches from the real one. Taped down beside it was a small box of bullets. Carl picked up the gun and turned it over slowly in his large hands. It was as small and flat as the water pistols he had played with as a child, but surprisingly heavy. In an indented circle above the handle was an Indian Chief and around it, in old-fashioned typeface, the words “Little Savage.”

What Carl felt, holding his grandfather’s gun, was the boyish elation of a lucky find. It was only later that the gun became mixed up with the things he thought about when he woke up at night.

At first, what he imagined was Ray’s face—how his expression would change when he saw the gun. Carl, Carl, Carl… and then what? Carl envisioned a hundred different scenarios: Ray falling to his knees, Ray begging and blubbering, Ray crapping his pants. These were all good, but after a while Carl needed more. He needed to see Ray hurt; he needed to know that Ray couldn’t just get back up off the floor and go back to being Ray. Slowly, the scenes Carl imagined shifted from threats to actual violence—beating on Ray’s face with the butt of the gun, kicking him; even, finally, shooting him.

But here the pure jet of Carl’s rage always shut off. The thrill of cutting Ray down to size would evaporate and a panicky, lost feeling would take its place. Carl would start worrying about logistics: how to get out of the building, and whether he’d be able to arrange a getaway car, and how to get to Mexico, and also, on particularly bad days, who else he might have to shoot.

Tonight what he was thinking about was Lisa: would he have to kill her, too? He saw again the disdain in her face as she turned back to her salad, and flushed. It was always like that with girls for him—it was always no, and forget about it, and what do you think you’re looking at?

He lay in the dark, eyes closed, imagining what Lisa would say when she saw the gun. Would she beg? Scream? Offer him a blow job? That was an interesting train of thought, but soon he was distracted by the question of how he would get to her desk before the cops came, because he’d have to do Ray first, of course, that was a given.

He tried to picture the fundraising area. Was her desk the one by the VP’s office? Or was it at the other end of the row of cubicles, by the water cooler? And what if she wasn’t at her desk, would he have to run around looking for her? After a while, without Carl’s noticing, his thoughts became magical and confused, until he and Lisa were together in a swimming pool, naked and smooth and wonderfully warm. She pulled him close and he put his arms around her, his hands clasping the two ends of the gun behind the small of her back. Lisa leaned in and whispered, “I can drive you.” She had the car running already, he could hear its horn beeping rhythmically in the background. Relief washed through him. Only why did she have to keep pushing his shoulder like that?

Carl woke with a jolt to find his roommate shaking him. The alarm on the digital clock was going off.

“Carl! Jesus Christ, are you deaf? That thing’s been beeping for, like, 10 minutes already.”

“Sorry,” Carl mumbled. He hit the button on the top of the clock and the sound cut off. It was 8:05, too late for anything but a quick change of clothes. He leaned back against the headboard and waited for his startled heart to slow.

Staring at the battered metal doorknob, Carl felt the cage of his life close in around him.

Usually, in the daylight, Carl’s idea—the idea of killing anyone—seemed nightmarish and absurd. But this morning, after he had put on his coat and shut the apartment door, he stood in the hallway for a minute. He felt shaky and weak, as though he’d just been bested in a fight. He wasn’t up to a day of work; even the idea of getting on the bus felt vaguely threatening. And of course, when he got there, Ray would be all over him because he was going to be late; there was nothing he could do about that now.

Staring at the battered metal doorknob, Carl felt the cage of his life close in around him. Quickly, before he could change his mind, he went back into the apartment and fished the gun out of the drawer.

Ray had a dream of his own. He dreamed about a puppy. Or maybe it was a lobster? It was hard to tell. He held it in the crook of his arm and its warmth spread through his chest. Later, when it was definitely a puppy, he took it for a walk through the mall. But then he realized he shouldn’t have—it was too weird looking, with that red shell, those little ball eyes sticking up on their stems; it just didn’t look like a puppy should look. He thought about maybe ditching it, opening one of the exit doors and unclipping the leash, giving it a little shove. But it broke his heart to think that, so he went on walking, stiff with shame.

Then a miraculous shift occurred. A young girl pointed at the lobster dog and cried, “How cute!” She came over, she bent down and patted the dog on its hard, red head. Other people stopped, too: teenage girls, mothers with baby strollers, other men. Everyone was friendly, everyone seemed to like Ray. They leaned toward him, smiling, and Ray smiled back. A weight seemed to lift off him; when he half-woke and rolled over, the bed felt softer.

He was still in a good mood when he got up in the morning. He flung back witty comments at the men on the morning talk show; he even thought, shaving, that his face looked a little angular, a little GQ-ish even. Outside, the warm spring air held a scent of flowers. He threw his keys up in the air and caught them, just for the hell of it.

But when he turned the key in the car’s ignition and heard the frantic, failing whinny of the starter, the mess of everything rose up before him again: things done wrong (leaving the headlights on, the new fundraising database), or still unsolved (the email server), or just not happening (sex, love, money—you name it), and then something else that had been nagging at the back of his mind, a problem from the day before. It didn’t come to him until later, while he was waiting for the AAA truck: Lisa in the lunchroom, the look on her face when Carl came in.

No, not when Carl came in—it was when Ray spoke to Carl. It was Ray she had been looking at when her eyes went hard.

Ray spread his hands out against the steering wheel and stared at the coarse black hairs on the backs of his fingers. Why had he spoken to Carl, anyway? He hadn’t wanted to talk to Carl; hell, he hadn’t even wanted him in the room. What Lisa said about her dream had brought about some change in the atmosphere: a thaw, a little opening, and sitting there, talking with her, he’d felt as though he might be on the verge of something. Then Carl showed up. Carl, with his big, reluctant body, his drawling Um, yeah. Did you run the backup, Carl? Um, yeah. Is the email server down again, Carl? Um, yeah. Could you get fucking clue, Carl? Um, yeah.

Ray had tried with Carl; no one could say he hadn’t. He’d sent him to classes, suggested books to read. He tried to be a mentor, he really did—he gave Carl pointers on a daily basis. But nothing seemed to get through: Carl’s large, slack face remained a stubborn blank. Just the way he moved was enough to drive a person crazy, just the way he dragged his feet over the carpet, as though the entire gravitational force of the earth was against him. And underneath, concealed by that expressionless face of his, a sneaky undercurrent of rebellion, of disrespect.

But Lisa had not seen all that. Lisa had seen Ray and what she had seen had disgusted her. A spasm of anger ran through him. He got out of the car and slammed the door. Where the hell was AAA?

When Ray stopped at Dunkin Donuts in the morning, he usually drank his coffee in his car in the office parking lot. That way he could listen to the radio and also avoid looking cheap for not picking up extras the way the VP of fundraising always did. But today, by the time the tow truck showed up and the car had been jumped, he was running nearly an hour late. He’d have to take his coffee into the office like everyone else. He barked his order at the Indian girl behind the register, put the exact change on the counter, and watched, irritated, while she carefully took a cup off the stack and poured in the coffee. She placed the lid on the cup and pressed around its entire circumference with one slender brown finger. For chrissake! Ray thought. It was ridiculous. Why have someone so slow on the morning shift? He made up his mind to complain about her to the manager. Then the girl looked up at him and smiled. Not a fake smile but a real one: her whole face lit up.

“There you are,” she said in her musical accent.

Ray took the cup from her outstretched hand. “Thank you,” he said stiffly. His tone was harsher than he’d intended, and as he turned away he saw her smile die away. He walked heavily toward the door, weighed down by a sudden gloom. Through the glass, he could see the bright spring light glittering on the cars, a triangle of blue sky, but these seemed as far away as the happiness he had felt earlier, something for other people to enjoy.

He spotted the girl’s face again the instant he turned around, shining like a beacon between the backs of the people in line. He took his place behind a construction worker and waited. “You know what?” he said in a friendlier voice when he reached the counter, “I think I’ll take one more.”

He was rewarded with another smile. “Most certainly,” the girl said. “How would you like that?”

Ray hesitated. He had turned around on instinct; he hadn’t actually decided who the extra coffee should be for. Lisa, he thought now. But then he remembered he was in trouble with Lisa; also, that he’d only ever seen her drinking tea. This brought him to Carl. Grudgingly, he let himself think it: the coffee should be for Carl. He’d bring the guy a coffee; show Lisa that he wasn’t whatever she thought he was back in the lunchroom yesterday. He pictured the half-drunk coffee Carl abandoned on his desk every day, the milky star on its surface. “Light, no sugar,” he told the girl.

“Light, no sugar,” she repeated.

It was the right thing to do, he could tell, because immediately he felt better. He took the two coffees and pushed open the glass door with his shoulder, his shoes crunching on the leftover winter sand by the curb. He put the cups in the car’s cup holders. When he turned the key, the engine started.

Carl was sitting at his desk with his jacket on. His head was buzzing with exhaustion or maybe hunger—he had skipped breakfast to make the bus. And now Ray wasn’t even there. At this thought, a fresh wave of anger washed through him and he pictured Ray again: Ray sneering, Ray gloating, Ray in the doorway saying his name. He reached into his coat and touched the gun. The cold metal seemed to transmit a shock. Was this it? Was he really going to do it?

This was the trouble with bringing a gun to work: you couldn’t stop thinking about it. Shoot Ray, don’t shoot Ray, shoot Ray—he’d been back and forth at least ten times already. He flipped the safety off and then on again, staring at the small patch of carpet between his feet, tired of trying to figure it out.

To the extent Carl had ever thought of the carpet, he’d thought of it as gray; now, though, he saw that it was a random mixture of colors—there were brown parts in it and even black. His eyes traced a strange, H-shaped group of brown nubs; then an anomalous patch of white. There was no pattern to it, really; in fact, he could see it was kind of a mess now that he looked at it. Still, it felt surprisingly good to sit there and stare. The office was quiet. No one walked past; even the hum of the servers was strangely muted. He seemed to be alone in a little bubble of timelessness. Slowly he let his eyes drift out of focus.

Time stretched out, a vast, featureless plain, then suddenly shrank to nothing: Ray, coming heavily down the hall. The door to his office opened and then shut, shaking the cheaply-made walls. For a few moments there was no sound. Then Carl heard Ray’s door open again. Heat flashed through him. This is it, he thought. A quick glance at the monitor was all Ray would need to see that he hadn’t done any of the morning tasks. For once, Carl deserved to be yelled at. He kept his eyes on the carpet. He sensed, rather than saw, that Ray had come to stand in the doorway.

Inside his coat pocket, Carl flipped off the safety.

“Carl, Carl, Carl,” Ray said.

Inside his coat pocket, Carl flipped off the safety.

Still moping, Ray thought. He held out the cup. “I stopped by Dunkin Donuts,” he said. But Carl didn’t look up; he was staring at the floor in the sullen, beast-of-burden way that drove Ray nuts.

Carl could feel his hand holding the gun, far away at the end of his arm. Now, he thought, I could do it now. Blood began to hammer in his head.

“Got you a coffee,” Ray said.

Coffee. The word snagged in Carl’s mind.

Ray stuck his arm out a little farther. “I stopped at Dunkin Donuts.”

Dimly, Carl registered the repetition, the out-thrust cup. Now here was a situation: Ray was sucking up to him. Or was this just a new way of dicking him around? His heart was so loud he couldn’t think. He adjusted his grip on the gun, waiting for a cue.

What happened next was something unexpected: there was a noise in the hallway, the brisk slap-slap-slap of someone walking in flip-flops.

“Oh, hey there!” Ray called out. “Good morning!”

There was something in his voice—a softness or even a pleading—that made Carl glance up. With a little shock of pleasure, he recognized Lisa’s dark head.

“Keepin’ busy, huh?” Ray said.

“Yep,” Lisa said, not bothering to look at him.

“What is it, crunch time for the annual?”

Carl could still see Lisa, she was just a few feet beyond Ray; it wasn’t possible that she hadn’t heard his question. And yet she kept walking, she turned the corner into the copy room with the end of her ponytail bouncing against her slender back.

Ray stared after her. “Annual appeal,” he said. “Lot of pressure on those girls.”

But nothing he said could cover for it: Carl had seen how she had treated him. The Ray who turned back toward him now, the Ray who stood in the doorway, his hand on the sill, was a different Ray—a blunted, weakened Ray. Carl let his eyes drop back to the rug.

“Anyway, here you go,” Ray said, holding the cup out again. “Light, no sugar, right?”

It came to Carl that he could just reach out and take it. He could let go of the gun and take the coffee, and all the ordinariness, the familiar nothingness of the rug, would remain as it was. He would not have to kill anyone, he would not have to run. He would not have to hunt Lisa down in the fundraising department. Carl’s mind halted.

In the doorway, Ray felt his eyes snap with irritation. The tension in his jaw was coming back. He forced himself to try again. “What, that’s not how you take it?” he said.

Carl scanned the muddle of gray and brown nubs, his mind trolling back. What was it? A pull like that of a still-warm bed, a promise—of sex or skin; a warm, naked tangling. He blinked, unable to remember. A fantasy, it must have been, or a dream; something that had no place in the cold light of the office. Slowly, as though he were waking from a trance, Carl raised his eyes. “No. No, I mean—yeah,” he said. “That’s how I have it. Light. No sugar.” He pulled his large hand out of his coat and took the cup.

“Okay, good,” Ray said. He let his breath out, inexplicably relieved. “Good,” he said again, as he stepped backward into the hall.

Carl held the cup with both hands. He could smell it now: the bitter coffee, the faint underlying sweetness of the cream. Ray’s head reappeared in the doorway. “Hey, ahh, don’t forget we’ve got that meeting on the new database at 11:00. Should be a real ball buster.”

“Yeah, I know,” Carl said. “Thanks,” he added, but Ray was already gone.

Walking back down the hallway with her copies, Lisa caught a glimpse of Carl through the open door, his head bent. He seemed to be cradling something in his hands. She froze in mid-step, alarmed. She had the odd impression it was something alive—a bird maybe, or a mouse. But when she glanced back, she spotted the familiar pink and orange logo between his fingers. It was only a cup of coffee. He was just trying to wake up, the poor slob.