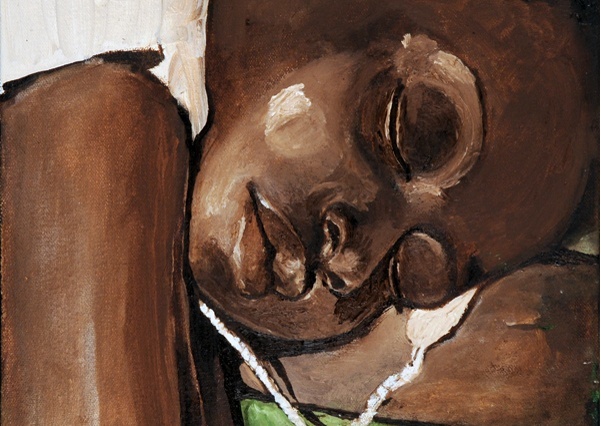

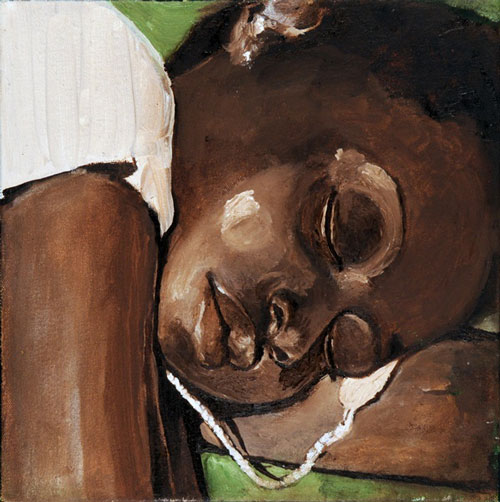

Rubell Family Collection, Miami, FL; courtesy of Roberts & Tilton, Culver City, California

R

everend Ezekiel Green squinted at the billboard erected in the field of grass gone past green, on its way to golden brown in the scorch of Texas sun. Built beyond the church’s parking lot three summers ago to catch the eyes of northbound travelers on the Martin Luther King Jr. highway, the sign was of his congregation’s love for him:

You who are broken, stop by the potter’s house.

You who need mending, stop by the potter’s house.

Give him the fragments of your broken life.

My friend, the Potter wants to put you back together again.

You Are Welcome At

Ephesus Baptist Church

Sunday Services 11:00 AM.

Every Sunday, Reverend Green sang the billboard’s lyrics in a raspy baritone as he welcomed strangers to join his church family or extended a sure hand to the young on their first step toward baptism. “The Potter’s House,” his signature tune and for many the high point of church service, held within its altered chords his testimony: a man not only beaten by life, but broken by it at every juncture: boyhood without a father; manhood without a mother; and now a loss so senseless he could not think of what to call it. For the last several months, Sister LouAnne embellished the song with poignant vamps, repeating phrases on the organ to which he improvised and shared what was in his heart.

The sound of motors revving past him as he unfastened his seatbelt, doubt lingering like the last bit of green on the Ephesus lawn. He stood beside his Lincoln Town Car, a gift from his congregation, or, as they had put it, a cherry to top all of the Sundays he had given them. That red car in the 10,000-square-foot parking lot gleamed like a ruby on a jeweler’s black cloth.

No one ever left Ephesus unless they moved to a distant city or went to meet their Maker.

The recent membership count amazed him; at 1,012 the congregation had grown by 182 in a single year. After thirty-three years they were still coming. More important, no one left. No one ever left Ephesus unless they moved to a distant city or went to meet their Maker. For these reasons the church board fought hard against his resignation. Several members questioned why he wanted to leave. Sister Hattie Grayson asked if he was sick. He assured them that the Lord was keeping him in good health. Remembering how Reverend Green had given them a loan for the purchase of their first house, Deacon Grayson dropped his head and stammered, “Ain’t right, then.” They reminded the Reverend of his anointing; said they were sure God wanted and needed to use him, still. They warned him that he wouldn’t know what to do with himself during retirement because he was put here to preach, and that was just all there was to it.

Ezekiel listened for two hours; it seemed his great-aunt had been right long ago when she’d said, “Boy, you talented at religion.” She had seen it in him when he was ten years old. Sitting on the porch snapping peas one Saturday evening, she waited until he finished reciting the tenth Beatitude and said to him with a face full of pride and seriousness, a face that nearly scared him, “Boy, you fixing to move a lot of hearts and change a few minds if you keep on with that Bible-speak.” He didn’t know what she meant, but he figured talent—any kind of talent—was a good thing.

Reverend Green fumbled for the right key under a purple awning that led to brass-framed stained-glass doors of red and gold. He stepped into the frigid vestibule. At the end of the hallway, before the stairs to the sanctuary, he stopped in front of the office door where his nameplate had once been. “Pringle.” He repeated the new senior pastor’s name, “Reverend Winston Pringle,” grateful that the congregants and church board were in accord on the election. Foolishly, he thought the ease with which they had chosen a new shepherd would make turning over his flock easier. But how could it ever be easy when his life had started there?

The way the story had been told to him it was 104 degrees the Sunday Reverend J. B. Tucker preached the sermon that filled the unborn baby with the Holy Spirit. The mother-to-be disrupted her row, stepping on the toes of people rocking to Reverend Tucker’s sermon. She waddled down the steps to the bathroom where she discovered it wasn’t urine that had wet her dress. Another flutter came, stronger than the one she felt at the start of the sermon.

Ezekiel Green’s fondest memories were all born in that place. As a boy he had liked to lean his head against the billowy bosom, damp from perspiration, of his great-aunt, who smelled of rosewater and butterscotch candy and would envelop him with one meaty arm while fanning them both with the other hand.

She leaned against the stall door, both hands on her belly, concentrating on the minister’s voice issuing from the speaker mounted high in the corner above her head: “See, there was these dried bones laying around and God told Ezekiel to prophesy to the bones. Told him to tell the bones, ‘I will make breath enter you.’ Well, Ezekiel said what God told him to say, and you know them bones started rattlin’ together… and flesh appeared on them… but there was no life in them. So God told Ezekiel to command the bones again, except this time to add ‘Lord’ to it. So Ezekiel said, ‘The Lord make breath enter you.’ And breath entered the bones and Ezekiel had him a whole army.” An usher entered the bathroom, exclaiming at the strange sight: two thick legs jutting out below a stall door. She found Ruth Green propped against the toilet, twisting and panting her way through the final stage of labor. The story made it all the way to Houston, even crossed Louisiana’s state line: Reverend J. B. Tucker preached so hard and so good, pregnant women gave birth in the church basement.

Ezekiel Green’s fondest memories were all born in that place. As a boy he had liked to lean his head against the billowy bosom, damp from perspiration, of his great-aunt, who smelled of rosewater and butterscotch candy and enveloped him with one meaty arm while fanning them both with the other hand. Church elders often asked him, “Boy, you love the Lord?”—a question to which Ezekiel always nodded yes. On Sundays, everyone waited cheerfully in bathroom lines, making happy small talk: Girl, you sure are wearing that hat! Or: Nice suit Mister So-and-So. Or: You must be feeling good cause Lord knows you look it. Ezekiel thought of his own manners, exemplary on Sundays. “Yes Ma’ams” and “No Sirs” came easy since, dressed in their very best, Ephesus members really did look like something.

Church brought out the best in everybody. And it brought out something else, too, that as a child Ezekiel could not articulate. He had noticed that during the week his mother had no joy, made evident by the persistent furrowed brow and words that stumbled midway through a sentence, causing her to re-order her thoughts like so: “Ezekiel, you need to come straight home from school tomorrow. Don’t stop and play nowhere cause… I’m losing my mind. What was I about to say… Oh yes, cause I need you to run some errands for me.”

Momma worried a lot. Sometimes she raised her voice at him or at no one and complained about things of no real consequence, like running out of milk or coming to the end of the aluminum foil. During the week all of these things added up, winding her so tightly that by Sunday morning she snapped. Ezekiel watched from his place in the third pew next to his great-aunt as his mother, seated in the first row of the choir, came undone. Sometimes it started during Reverend Tucker’s sermon. She’d begin to rock slowly back and forth, back and forth. Sometimes it started during a choir member’s solo—her shoulders hunching up and down repeatedly, like the valves of his trumpet. No matter how it began, it wasn’t long before his mother’s tears flowed like wine at the Cana wedding.

On most Sundays, Ezekiel waited for his mother in the vestibule after the benediction. She took her time disrobing and socializing with the other choir members in the room he was not allowed to enter. When she found him, choir robe covered snugly in plastic flung over her arm and lipstick freshly applied, he always gave her a tight squeeze around the waist. Then he’d ask the same question: “Momma, why do you cry?”

“Aw, baby,” she would say, flashing a bright smile he would not see again for seven whole days.

In middle school, Ezekiel looked to the men of the church for lessons on how to become a man. No one knew the whereabouts of his own father, and his mother forbade him from playing outside of the pool hall, let alone going inside. She even escorted him to the barbershop. So Deacon Grayson, who taught him how to knot his tie better than his mother could, took him aside when he got to be eleven or twelve and told him he was big enough to get a paper route and start keeping a little change on him. Mr. Kilson, an usher, had unknowingly taught him a thing or two about deportment. The young Ezekiel liked the way he walked and stood and made subtle gestures with his hands when he spoke. The janitor and groundskeeper, Mr. Simmons, who always completed a thought with “mind your momma, boy,” had told him when he started his last year of high school, “When you meet a nice lady just think of all she’s had to do to become that way and don’t you do nothing to make her work hard in vain. In other words, if you can’t add to her, leave her alone. But be a man, don’t take nothing away from her.”

On a full scholarship from the University of Texas, Ezekiel earned a degree in political science. Angry with God for taking his great-aunt and mother during his first year, he had rethought declaring religion for a major. Tucked away in the back of his mind, though, was the awareness that practically every black male politician was also a preacher, so he was still surreptitiously on track should he decide to call a truce with God.

In Austin he met Iyantha, a student at Huston-Tillotson College visiting UT to inquire about its graduate program in education. He saw his wife-to-be on the steps of Blanton Hall, and forgot where he was headed. They were married after she completed the program and moved to Dallas, where Ezekiel enrolled at the Dallas Bible Institute. His thesis, on the epistles of Paul, cemented his love of the apostle’s writings and inspired the naming of the only child Iyantha would give him. The summer of his son’s birth he attended the annual Ephesus Baptist Church picnic, where Reverend Tucker pulled him to the side.

“There’s a calling on your life, Ezekiel. Been there ever since you were born. What are your plans now?”

“I don’t exactly have a plan—except we like this area and plan to stay. I suspect I’ll find a job and wait until a post opens up for me at one of the churches.”

“I imagine you been real prayerful about the situation. Trusting in the Lord with all thine heart, leaning not to thy own understanding, like the Good Book says. While you thinking and praying on it, though, I wanna tell you Reverend Mack is leaving the church. He’s moving to Oklahoma City to lead his own congregation. I’ll be without an assistant pastor. The post is yours if you want it.”

Thirty-four years ago Ezekiel had accepted the assistant pastorship and when Reverend Tucker died of a heart attack one year later, the decision was unanimous: the church voted in the preacher born in the basement.

When the young people left in droves for whatever pubescent Christians do on Sunday mornings after they quit the church, Ezekiel decided to fight fire with fire.

Under Ezekiel’s leadership Ephesus prospered: remodeling begun under Rev. J.B. Tucker was completed, the thirty-one-year mortgage burned; church staff expanded; a newsletter launched; a motor coach and several buses purchased; national and international conventions hosted; and a radio broadcast aired live every Sunday. Recently, they had purchased the retreat facility they had rented for years.

For four years the church’s Women’s Guild had sold dinners in order to raise money for a daycare center that would serve not only their congregation, but the entire community. Even those who had not deigned to set foot in the church on Sunday signed the waiting list. Something about their child being in a church daycare made them feel safe. One morning Ezekiel dropped by, unannounced. A little past nine in the morning, a woman entered wearing a tube top and a pair of Daisy Duke shorts, with a can of beer in one hand and her little girl’s hand in the other. A teacher who had just ended her tour with the reverend gave him a wide-eyed look of concern. He couldn’t help but see his own granddaughter in the little girl, so he smiled at the teacher and motioned for her to welcome the mother and child. “That child needs us,” Ezekiel said. “All you have to do is look at the momma to see the child’s need. If there isn’t room, make room for that one.”

When the young people left in droves for whatever pubescent Christians do on Sunday mornings after they quit the church, Ezekiel decided to fight fire with fire. He prayed for an answer, a way to lure his teenagers back. One evening while flipping through the channels, he paused at BET to watch a rap video. If he ignored the degrading words, he understood why the youngsters found the music exciting—hard not to with the relentless beats and all the flash of the rappers. The next morning he called Ms. Young, a music teacher at the high school, and asked her to start a teen Christian rap group. He suggested she encourage the young people to write their own rap lyrics at choir rehearsal and to use the Bible as their source. He bought video equipment so they could make music videos at the church. When Ms. Young approached him with the kids’ idea to make a CD, he consented so long as all proceeds established the Ephesus Baptist Church College Fund. And that was how he went from being Reverend Green, with twenty-four teenagers in a congregation of nearly seven hundred, to MC (Missionary for Christ) Zeke, as the young folks, whose numbers quickly surpassed one hundred, called him.

Now Ezekiel took a seat in the corner of the last pew in the same spot he had often sat to have a little talk with God. Before him, water flowed into the baptismal pool from a recent installation—gilded pitchers held by three gold-plated cherubs, behind them the setting sun’s orange glow illuminating the crucifixion scene on the stained-glass window. He squeezed his eyes shut on a painful image engraved on his memory: the frightened and beautiful face of his granddaughter looking at him with the starriest eyes he’d ever seen. Together they stood in the baptismal pool, Tasha trembling as the water that only reached her grandfather’s waist bobbed against her chin. Ezekiel placed one hand behind her back. Tasha crossed her arms over her chest as she had been told in rehearsal. “Father God, I give this child to you,” he began, laying the other hand across her forehead and then slowly pushing her back. “She was one of yours,” he said now in a voice so weak he did not recognize it as his own. “And yet you forsook her.”

Ezekiel looked at his watch, then around the church, and way up in the rafters above the baptismal pool where he saw Iyantha. There was no material likeness of her anywhere but he saw her just as plain. He blamed it on his thinking, he had thought hard about her lately. She was hurting just the same as him but he had felt too empty to give her anything to help. He wiped his eyes but Iyantha was still way up there, hovering over the baptismal pool. He saw this as the will of God, and kept looking until he could see himself, too, beside her in a way that he had not been for months. Maybe even years. Yes, he had made the right decision. Leaving Ephesus would be good for them even if it was good for nobody else.

Six months ago the decision to leave his post as senior pastor had wrenched his conscience. “I’m going to run this race for the Lord for as long as He sees fit,” had been his vow to Iyantha over the years, steeped in the belief that he had a special anointing from the Lord; there could be no other explanation for the fire he felt when he preached. Ezekiel entered a pact with God: should his trust in him flicker or the flame of his passion for The Word dwindle to an ember, he would no longer preach the gospel, though he could not fathom either would come to pass.

A telephone call from his son relaying the Saturday afternoon visit from a pair of Casualty Assistance Calls Officers broke the pact. The CACOs notified Paul and Cheryl of Tasha’s death. A roadside bomb, which the men had referred to as an “improvised explosive device,” went off as her convoy passed Fallujah. With no words of comfort for his son, Ezekiel simply handed the phone to Iyantha. Alone in his study, he looked down on his desk at the reply he had begun in response to his granddaughter’s latest letter. He removed Tasha’s letter from his Bible where he’d tucked it to inspire a future sermon. From the front of the house he heard Iyantha cry out, “Lord Jesus. Lord Jesus.” He read:

Dear Paw Paw,

Yesterday I saw two young boys get shot down outside of a mosque. They looked to be about fourteen or fifteen. It is hard to see something like that and not question your faith. I don’t mean to disappoint you but I’m writing to you because of all people, you can help me stay strong while I’m over here. I have not seen other people get killed like I saw those two boys but the gunshots and explosions go on all of the time. Somebody told me you learn not to hear it but I’ve been here seven weeks and I still do. I have a friend here, a girl from Midland. And Ricky and I talk or write letters as much as we can. I have seen him once. He’s holding it together in Baghdad. He’s changed a lot, Paw Paw. Hard to believe he’s been over there a year. When we talk I try to focus on the future, our wedding plans.

I tell Ricky it’ll help to look forward to life after this. He says it won’t. Don’t worry, though. You’ll get your great-grands one of these days.

This morning when I woke up the day was all orange, the sky and everything. It was beautiful, and then the shots rang out and I thought of the two young boys from yesterday. When I look around here I think of the pictures I had in my mind of biblical places when I was little. I remember looking at those maps at the back of the Bible you gave me when I was baptized. I think some of the places back then must’ve looked like this.

How is everybody at Ephesus? I miss you and I miss grandma—especially her chicken-fried steak, mashed potatoes, and pecan pie. Please tell her I said so. And, please pray for me. Pray for us all.

Love, Tasha.

Despite his wife’s grief, the news was not real for Ezekiel until drinking his morning coffee over the Fort Worth Star-Telegram two days later. Even then, he did not react but excused himself from the table to retrieve a pair of scissors from his study. Upon his return, he clipped out a tiny portion from the paper that read “Pfc. Tasha L. Green, 20, Fort Worth, Texas, died in convoy attack in Fallujah, Iraq, May 27.”

When her body was flown from Iraq to Dallas/Fort Worth International, the four of them—his wife, son, and daughter-in-law—were present to greet it. They held hands on the airport tarmac as two soldiers appeared in the doorway of the plane, lifting a casket clothed in red, white, and blue. Paul released hands first, bending at the waist and covering his face. He moaned loudly while his stammering wife pummeled his back with her fists. “Paul, no. That’s not my baby in there. That ain’t none-a Tasha. That’s not our baby in there!” Iyantha turned her back on the scene, dropping her head in a silent cry. Only Ezekiel stood tall as the flag-draped coffin moved down the conveyor belt toward his torn family. In that moment his flame for the gospel flickered and died.

A few nights later Iyantha was sharing a lighthearted story about one of the kids in vacation Bible school, spooning mashed potatoes onto her husband’s plate, when Ezekiel raised his voice impatiently. “Don’t give me so many—save some for Tasha.” He pushed back from the table and sat staring into his lap for a long time, then said in a low voice, “Lord, help me.”

The congregation grieved hard for the pastor and his family. Their tidings, in the form of flowers, food, cards, and money, did not stop for weeks.

Ephesus had witnessed many funerals, but never before had the deceased been a soldier. Two officers from Fort Hood’s Fourth Infantry Division presented a folded flag to Paul and Cheryl as a recording of “Taps” played over the church P.A. system. The congregation grieved hard for the pastor and his family. Their tidings, in the form of flowers, food, cards, and money, did not stop for weeks. Not until Ezekiel addressed them: “Saints, the Green family appreciates your thoughtful gestures and loving gifts during our difficult hour, but there is no reason to continue. We accept the Lord’s will and do not want to offend the Almighty’s judgment with our grief. To do so is to send the message that we don’t trust the Lord’s infinite wisdom. I believe that the Lord called Tasha home early for a reason. We are glad that she is with her Maker.”

They had expected a fiery anti-war sermon fueled by his granddaughter’s death, but in the subsequent Sundays Ezekiel’s preaching cooled to lukewarm teachings from the Old Testament. And even then he struggled to give them a positive word to take away. His private prayers changed. Where he had always used prayer to offer praises and thanksgiving, he now used it for inquiry. He asked the Lord to please make sense of Tasha’s death for him, to reveal to him how he should serve and lead the church with so little hope and so much confusion. When the answers didn’t come, he prayed more fervently, asking for patience like Job’s. With this patience he ministered to the church for six months after his granddaughter’s death.

His last Sunday morning as senior pastor, Ezekiel knelt at the first step of the pulpit and whispered the same short prayer he had sent up to the Lord for thirty-three years. “Dear Lord, edify the words of my mouth so that they may be acceptable in thy sight.” Once seated in the giant oak chair on the pulpit that rose dramatically above the congregation, Sister Lou Anne struck an organ key. The assistant pastor rose from one of the two smaller chairs flanking the reverend and spoke into the microphone: “Those of you who are able, please rise.”

The rustling of church bulletins, fans, Bibles, and pocketbooks accompanied Sister Lou Anne’s prelude. At the rear of the church two sets of double doors in opposite corners flew open. No sight pleased Ezekiel more than the one hundred choir members swaying into the sanctuary in kelly-green robes as vibrant as late spring with flowing gold satin sashes bright as the sun. Their voices robust and cheerful, they marched, bouncing a little on the left foot and then the right, right hands held in the air, left hands behind their backs. He recalled how in the past he had felt like a king as they closed in around him, his faithful and loving soldiers. That Sunday the feeling almost returned when their mouths opened so wide, yearning to please their Master, and him, too. Today more than any other Sunday he felt they wanted to reach him with their song; his favorite tenor belting from the back of the line; the organ, bass, and drums locking the congregation in rollicking rhythm as the choir swelled to heightened frenzy (“My word,” Iyantha would say later, “they wanted to send the roof flying off!”):

Step to Jesus and everything will be all right;

Step to Jesus he’ll be your guiding light;

Step to Jesus all your battles he will help you fight;

Step to Jesus he’ll make everything all right;

If you feel you can’t go on, pray the Lord will make you strong;

A heart-fixer is he, there is nothing he does not see…

When the choir filed into their pews behind the pulpit, Ezekiel approached the lectern to begin the responsive reading. As a child, Tasha had enjoyed this portion of the service most. Even as the church grew to seven hundred, he could hear her voice, uniquely robust for a little girl, reading above all of the others.

“This morning’s responsive reading comes from Psalm 27, verses one through four, ten, and thirteen.” He had given the Psalm of Protection to Tasha before she left for Iraq. He closed his eyes, recited from memory. “The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom shall I fear? The Lord is the strength of my life, of whom shall I be afraid?” Soft Amens rippled through the congregation. “When the wicked, even mine enemies and my foes, came upon me to eat up my flesh, they stumbled and fell. Though an host should encamp against me, my heart shall not fear; though war should rise against me, in this will I be confident.” These words weighted his heart now. He wondered if Tasha had been confident in her last hour. Had the faith she questioned in her letter returned?

“For in the time of trouble he shall hide me in his pavilion: in the secret of his tabernacle shall he hide me: he shall set me up upon a rock.” So he had promised but it was not so. He had not set Tasha upon a rock.

Baskets for tithes and offerings changed hands quickly down each row while Sister Lou Anne played softly. Ezekiel started to sing: “There’s pow’r in the blood, pow’r in the blood.” And the congregants followed with: “There’s won-der-work-ing pow’r, in the blood (in the blood) of the lamb. There’s pow’r, pow’r, won-der-work-ing pow’r in the pre-cious blood of the lamb.” They repeated the song many times, as though casting a spell. Those who entered a trance did so not only by singing along but by recalling the delicious memory of their deliverance. When all the baskets were carried to the front of the church by men and women in black suits, green ties, and brilliant white gloves, Sister Lou Anne played the doxology and everyone’s voices rose, “Praise God from Whom all blessings flow…”

The deacons disappeared through side doors with the baskets overflowing with checks and cash as Ezekiel began a prayer of thanksgiving: “Father, I stretch my hands to Thee. No other help I know. If Thou withdraw Thyself from me, O whither shall I go?”

During his sermon, Iyantha watched closely. She paid little attention to what her husband said, so rapt was she in her prayer that he make it through the sermon all right. He had tossed and turned during the night like the ship carrying Jonah, ate breakfast silently, and only checked to make sure her seatbelt was fastened in the car on the too-quiet drive to church. She had placed her hand over his on the steering wheel when they pulled into the church parking lot. “You can stay on as pastor emeritus,” she’d said. “I’m sure they’d allow it. You are so loved.” He grunted that his work for the Lord had ended.

The soft drone of central air conditioning, an intermittent “Amen,” a cough, and an infant’s cry of discomfort were heard beneath the amplified voice of the preacher. Ezekiel fumbled through the sermon, repeating himself often, wiping his eyes. His faithful sent up prayers of their own that Reverend Green would have a change of heart.

The lights dimmed in the main vestibule as Deacon Hayward, charged with lighting the five-foot candelabra near both pulpit entrances, went to work. Ezekiel and Reverend Pringle began the ritual preparation of the wine and bread while the church softly sang: “Let us break bread together on our knees (on our knees)…” When the last communion-takers returned to their seats, Iyantha sat down at the piano. She accompanied her husband on “The Potter’s House” sung during the invitation to discipleship. During the last month many longtime members had requested special prayers. They walked to the front of the church below the pulpit where the minister stood and whispered in his ear the details of their family issues, financial worries, or health problems. But in four Sundays no one had accepted his invitation to join the church, which Ezekiel read as a sign that God no longer had intention to use him.

He concluded the verse with closed eyes, unaware of the young woman leaving her seat for the red-carpeted aisle that would lead her to him. “No more than twenty,” he thought as he pulled her close. His shoulders curled toward her, his knees bent in order to lay his head in the crook of her perfumed neck. In this pose, he whimpered like a baby fighting his sleep. “Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, Jeeesus,” his voice quivered into the tiny microphone clipped on his robe. To bear up under the weight of the man was too much for the petite woman, whose knees trembled, sending Iyantha from the piano bench to her husband’s side.

Iyantha’s hand on his back, Ezekiel finally released the young woman. Sweat rushed from his brow as he offered the stranger a sad smile. “Are you here to accept the Lord as your personal savior?” His words sounded like gravel. The young woman gulped hard, “Yes.” He did not ask the young woman’s name, where she was from, or any of the questions usually directed at new members. “Bless your heart. Do you accept the Lord as your personal savior?” The young woman looked to Deacon Grayson standing nearby. In three months of visits to Ephesus she had not seen Reverend Green ask anyone this question twice. In a high-pitched and tearful voice he repeated, “Do you accept the Lord as your personal savior?” Iyantha peeled her husband’s hand from the young woman’s shoulder, clasping it in her own. “Ezekiel. Ezekiel. It’s all right now, honey. It’s all right.” The congregation overheard as the microphone caught all of the whisper. She motioned for Deacon Grayson to help her lead her husband away as Reverend Pringle stepped up to the lectern.

—For ALM