It wasn’t common during socialism for families to have three children. They either had one or two, or none. In our building, only our family and the gypsies on the second floor had three kids. That always made me suspicious. I would look at my mother’s long dark hair, dark makeup, and peculiar taste in bright colors and I’d be like: There’s no way she is not a gypsy.

I have a birthmark above my butt, which is undeniable proof of gypsiness, ask anyone. Birthmark above the butt, and a small dot under any number 3 in your passport—this was how you knew you were a gypsy, according to the kids in my building.

My mother’s official version was that when she was pregnant with me (out of wedlock, let the record show), she stole a plum. When they caught her, she hid it behind her back. If a pregnant woman steals or was startled and then touches her face or body, her baby will have a birthmark in the shape of the stolen thing at the same spot she touched. So pregnant women would often throw their hands away from themselves whenever they stole or when they were afraid of something. You often saw these women, standing like balls with two arms sticking out on each side, like snowmen. Whenever I saw a pregnant woman I would run in the opposite direction. I didn’t want to be near the hands that left marks on everything they touched.

“Why didn’t you buy a pound of plums? Or just ask politely for one. Why would you steal like a gypsy?”

“Hormones,” she answered. ”You don’t think properly when you’re pregnant, you’ll see.”

“I don’t want to see, I’m ten.”

“Plus,” she added, “I could always find you by your birthmark if you got lost.”

My mother quit stealing after I was born, so my brother and sister ended up with no birthmarks and were jealous of me. They lived in constant fear that sooner or later she’d lose them somewhere. It was just a matter of when. Buses and trains were torture. A trip to the women’s market in the center of the city always turned into a tragedy. My siblings screamed and refused to get on the bus, because if the doors closed before my mother got on, that would be the end. We’d never see them again. They would live between umbrellas and purses in the lost and found department, until they turned ninety, no one to recognize them.

Because of this fear of separation we learned to love each other and cherish moments of togetherness, since any one of them might be our last. While trains and buses roared around like kidnapping machines, we were obsessively holding onto hands, legs, hair, and parts of each other’s clothes, so we could literally be in touch.

Some days our parents called us Huns, because of our excessive running around, yelling and breaking property. My mother yelled at us that grass was not going to grow in our wake. We were happy to have this power, though we didn’t know how to use it in our small apartment. Other times, my parents looked at each other and said, “Barbarians.” We were proud since any agreement between those two was rare.

Our barbarian days went something like this:

The three of us, smelly and itchy, clinging to each other, waiting for the gasoline and vinegar in our hair to start the killing. We had lice. Our heads were wrapped in bright turbans made from my mother’s old hippie skirts. She was reading my left palm to see if I was going to pass my math test. With one hand, my sister was holding my nose, and with the other she was drawing skulls and bones on my brother’s arm with a red pen. With his left hand he was holding her foot, and with his right, the table. We were always prepared in case somebody tried to separate us by force.

Fighting parasites was a big part of life, especially when you had so much life running around in your tiny apartment.

Loud arias from Carmen would waft in from the living room radio. They were the background my father needed to get a tick out of Charlie’s ear. Charlie was our Irish setter, named after Charlie Chaplin. Carmen, herself a barbarian of some sort, had moments where she sang too high, and Charlie howled with her for a while, then lay his head back obediently on my father’s lap to be cleaned. Fighting parasites was a big part of life, especially when you had so much life running around in your tiny apartment.

My father was an artist and the biggest opera lover I knew. He wasn’t an opera goer though, because as he’d explain it, he didn’t own a suit to go in. He’d worn a suit only once in his life, on his wedding day, and even that one had been borrowed. That was proof he wasn’t a gypsy, because they wore suits all the time. Dirty, shaggy, wrinkled, but suits, nevertheless. But on the other hand, as my grandmother liked to repeat daily, “Whoever you join, that’s who you become,” meaning—he’d joined my mother, and become a gypsy.

We had reasonably normal childhoods for a bunch of barbarians, and our days continued something like this:

The toilet seat fell thunderously every fifteen minutes; the faucets ran noisily all the time; the TV, the radio, and the parakeets were competitive chirping, volume on max, all of them winning. In the same time slot and on the same channel, you could also listen to a battle between the phone, the doorbell, and the dog. The apartment smelled of burnt toast, or cake, or hair. Somebody was yelling at somebody else, I’m not going to name names, because I was asked not to air my family’s dirty laundry, but all the yellers and the yellees were blood-related. Outside, three car alarms, with the complicated new five-song repertoire, were ringing simultaneously. A big night for car thieves, but at least those were two problems we didn’t have to deal with: first, we didn’t own a car, and second, our tribe didn’t steal anymore.

My mother took out the garbage (lice, ticks, and everything else), tied up the bag, and dropped it in front of our door—not next to it, in front. She expected one of us to trip on it, feel guilty, and take it down to the dumpster. We never did. The four of us and the dog would jump over the trash bag and continue about our day. The neighbor, a respectable man in a suit and also a huge opera fan, would cave in and throw it out for us. But my mother was convinced that one of us had done it, and was pleased with her modern pedagogical techniques. The neighbor stopped saying hello, but continued to throw out our trash, out of civic duty or pity. For some reason, we didn’t care.

Money was a dirty word, my father thought. His encounters with money went something like this:

He would hold the money, in small denominations, away from his body. With his elbow, he would push away the opponent’s hand offering him money in a battle over who should pay for a cup of coffee. He somehow always won, and paid, and then turned back to us to explain that it is not a matter of money, but rather of dignity. He had enough dignity to pay off Bulgaria’s national debt, but did not have the money.

My mother would shout at him, “How can you be so naïve, beh?” They never cursed but instead used “beh”—an insulting way of addressing someone by making him sound stupid and stubborn, like a cross between a sheep and a mule. We were told to not say “beh” but they always would.

“And why are you so mercantile, beh?” he would shout from the other room and slam the door.

She would run after him, open the door, and wave her broom threateningly, because she was constantly “cooking, cleaning, and doing laundry” (and liked to chant it in that order, too).

“Who are you calling mercantile, beh, if I was mercantile would I be married to an artist?” This is pronounced with a grimace of disgust and irony.

“Oh, village woman, you will never understand!” (probably a line from Verdi), and he slams the door in her face. She opens the door and yells, “Who are you calling a village woman, beh? Varna is a European city! Look at where you were born!” He knew he was the one born in a village, during a World War II evacuation. And this would go on for as long as needed.

This is how a suicide attempt became the only option.

I locked myself in the bathroom, the only room with a key, and studied for a math test in the empty bathtub. Ignoring the knocking on the door, I periodically flushed the toilet, to make it all sound real. I was enjoying (you may say) privacy, only that the word did not exist in Bulgarian, neither did the concept. I wrote my equations on the mirror with a piece of soap, even though I knew I wasn’t supposed to write on mirrors. You were also not supposed to look at yourself in the mirror in the dark, because you would become ugly. And most of all you were not supposed to break the mirror, which somehow I managed to do by pressing too hard with the soap. Seven years of bad luck were to follow.

This is how a suicide attempt became the only option. I decided to leave the apartment so as not to contaminate them all with the bad luck I was to bring. Next to the giant dumpster in front of the apartment building was the big gray electrical box with a red sign “Do not touch, dangerous for your life” and a drawing of a lightning bolt and a skull and crossbones below it.

I went and touched. I don’t remember how long I stayed there quietly crying (I was always a quiet person). There were things in life I loved and only realized it after I touched the box. Red sugar roosters and bunnies, merry-go-rounds, hot dogs, Pif magazine, my brother and sister, and most of all, swimming with a life preserver.

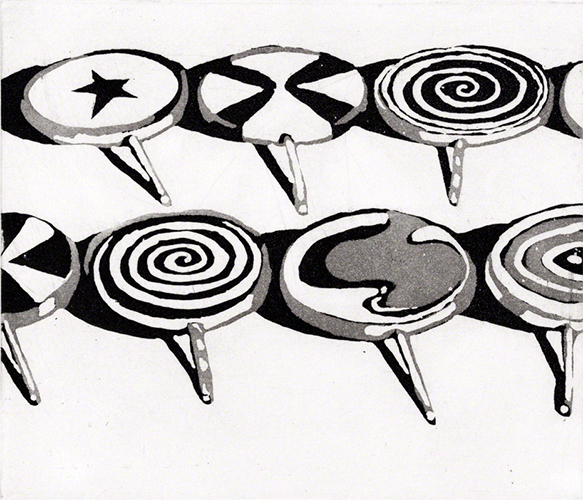

While I was waiting for death to come and take me to a better place, Crazy Mary appeared out of nowhere. We were all afraid of her and her cartful of cardboard to recycle. She was always yelling at kids and waving around a gun-shaped lollipop. She always carried some of those with her and tried to get children to come closer. She looked like the witch from Hansel and Gretel, enticing you with sweets to fatten you up so she could eat you. We would scream and run away as fast as we could. Somehow on the day of my suicide attempt I didn’t run. I took the revolver from her. She patted me on the head and took my hand and moved it way from the electrical box. Then she left. The candy revolver tasted really good and lasted twice as long as a sugar rooster. But it was more expensive.

Realizing I was immortal, I started betting with the neighborhood kids that for twenty cents I could touch the skull and crossbones box. I decided to buy a bike, and I would only need to touch the box 425 more times. But there weren’t that many kids in the building, so around the eighteenth time my enterprise slowed down. I didn’t have enough for the whole bike, only for a handlebar and maybe a bell. I went and purchased all the lollipop revolvers they had in the store and distributed them fairly between my friends and family. We stayed in front of the skull and crossbones sign like a bunch of savages, sugar guns in our mouths, and in the eyes—no fear whatsoever.