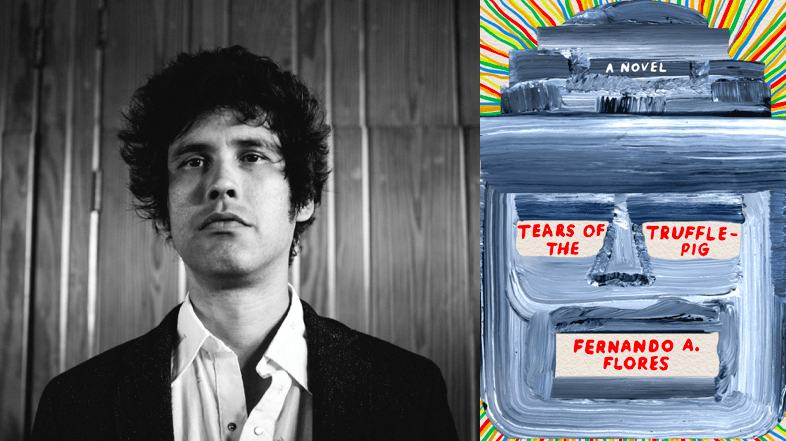

Welcome to the trippy parallel universe of Fernando A. Flores’s forthcoming debut novel, Tears of the Trufflepig. Set on the border of South Texas and Mexico, the book follows Esteban Bellacosa, whose attempts to lead a simple life after the loss of his wife and daughter are thwarted when he encounters journalist Paco Herbert. His new companion scores him a hot ticket to an illegal underground dinner serving “filtered” animals—animals scientifically brought back from extinction to entertain and feed the super-rich—and things become increasingly treacherous from there. Bellacosa takes an interest in the Trufflepig, a mythical creature at the dinner party once worshipped by the thought-to-be-disappeared Aranaña Indian tribe, and he subsequently embarks on a journey of flame-shooting border walls, a heist of ancient Olmec artifacts, crime syndicates at every turn, and, for all its absurdity, a surprising amount of sobering parallels to our current behavior as a society.

Never read anything like it before? Neither had I. I reached Flores over email and via Google docs to get to the bottom of his imaginative new book.

— KrisAnne Madaus for Guernica.

Guernica: You’re a bookseller in Austin. Tell me about your bookstore and your journey to write. You’ve written a book of stories, but this is your debut novel, and it’s not a safe one. How did you get it published?

Fernando A. Flores: Yes, I’m a bookseller at Malvern Books, where we specialize in poetry and fiction from indie presses. I started working there in September 2014, when, within a matter of a few weeks, I won an honorable mention award from the Alfredo Cisneros Del Moral Foundation, was laid off from my job as a barista, and had gotten hired at Malvern to work only two or three days a week. I wrote the first draft of this book on my typewriter in three months starting in October of that year. I wrote out of straight-up fear—fear I’d run out of prize money and would have nothing to show for it. After I finished, a couple writers I’d befriended gave me some advice about querying agents; then I did that until I found my incredible agent. It was probably my first time receiving real criticism from anybody based on a raw piece of writing. After signing with her, I revised it two or three times before it was sent out, and I really learned a lot about the editorial process, which was something I’d never really had practice with before.

Guernica: Had you not been in survival mode, what kind of book would Tears of the Trufflepig be?

Flores: Honestly, it would probably be more or less the same novel. But the way the project was written dictated the type of project it became, so there was no other way it could’ve happened, and I knew this at the time, too. I was very influenced by narratives that don’t relent in driving character and narrative forward, works such as Macbeth and The Girls of Slender Means by Muriel Spark. What kind of book would the first part of Don Quixote be if Cervantes wasn’t in jail? How would Kafka’s oeuvre be different if he’d had more time to write and wasn’t sick? I pay attention to the way I write my projects, because I believe that the energy exerted while writing can come across when reading. Which is why I have to hype myself up mentally before finally sitting down and getting the first word down. After the first word, the rest just spills out, usually.

Guernica: There is a current of energy running through this book, for sure, and it doesn’t just go away when you finish reading it. With the rhythm and pacing, too, you can tell music was involved. Which brings us to the really incredible nine-song Spotify playlist that accompanies the novel. Instead of easing my book hangover, the music kept me in the circuitous world of the book. I felt like a piece of clothing spinning in the dryer. How did music influence you as you wrote?

Flores: I’m very glad you enjoyed the playlist; thank you for listening. One of my great interests is finding old recordings of music, usually found in compilations that are often hard to come by. I guess I’m interested in music before the idea of recorded music. What was music before the idea of a radio hit single, or a commercial? Can anybody really tell me? I’m interested more in the regular people who would get together and play music, the kinds of tales or warnings that were handed down through songs, and, most importantly, the psychedelic time signatures. And not just from the US or Mexico, but I’m interested in the earliest recorded music of the world, which gives me a certain landscape, a certain texture that is hard to come by. I feel a lot of this novel derives from those textures.

Guernica: And what about the humor? Without the humor this would be a very heavy narrative, but with it, it’s more like a tragic circus. It does really feel like the “Circling Pigeons Waltz,” which is one of the songs from the Spotify list. Can you tell us about how conscious you were of these moments of levity while writing?

Flores: Something that occasionally bothers me about most literary novels is how stark they are, how devoid they can be of the humor and absurdism that surrounds our lives. Nothing is ever just completely stark and singular in its tone. Even in our darkest moments, something peripheral is often funny, or absurd at the very least. But, at the same time, I’m suspicious of deliberate humor, so I always avoid being deliberate in anything I do. That song, “Circling Pigeons Waltz,” is something special. Almost every day, before writing, I’d listen to this song probably eight to ten times in a row, pacing in a circle, before I’d finally sit down to write. I always had to remind myself that no matter what this novel was, it had to be like this song. It had to follow its timing and its rhythm and its strangeness, translated into narrative.

Guernica: What about the role of imagination? I kept looking things up I thought might have a kernel of truth to them. The huarango thorns used to stitch the mouths of soon-to-be shrunken heads are real, but the tribe attributed to the shrunken heads—the Aranaña—is not. Can you tell us about the interplay between research and invention?

Flores: Upon starting this project I really wanted to write what I called the “anti-research” novel. If I stumbled upon a piece of information, I would use it, but if I needed to find out something about a certain subject, or a landscape, I didn’t do research—I just wrote it. In this book, I knew there had to be the story of the Aranaña people, and I didn’t feel comfortable with researching existing indigenous cultures or histories, or anything like that. This novel began with the vision of the Trufflepig—what is it? It was probably very early 2014 when the vision of the Trufflepig came to me, so in many ways this novel is the research itself. I’m interested in fiction as research into the subconscious, and I really wanted to dig in and discover what the Trufflepig is. I’m still always learning about the Trufflepig, to this day.

Guernica: I wanted to ask you about other inventions, like the beliefs the general public holds when it comes to the American West. We see this, too, in your book. The protagonist studies a painting and sees “an image seemingly of the American frontier: cowboys driving cattle across a shallow stream in a junglelike terrain with red snakes coiled around sharinga rubber trees. The setting was very unlike the landscape of Texas, or the old west.” What do you think is the greatest misunderstanding people have about Texas and the border?

Flores: To be honest, I have no idea how other people perceive this place. Something about Texas, however, that I’ve always seen, that comes across in its underground music and visual art but not so much in its literature, is how surreal this place is, how psychedelic. I’m always wondering about the stories here, about all the lost stories. What type of stories existed in this land before 1492? I bet the oldest stories of this land were fantastical in essence. In writing this book, I was perhaps trying to access some of these, trying to understand what literature in this part of the world could have been without the influence of Europe.

Guernica: In a previous interview about your short story collection, you said, “If there’s anything political in any of these stories, it just appeared,” and that you weren’t “trying to smuggle in any political stuff.” What about in this novel?

Flores: The same definitely applied here. I never set out to write anything political. At the time when I wrote this, I was merely trying to harness all the crazy energy in my life to maintain some kind of creative equilibrium. All these heavy themes appear in the book because that’s what the story wanted to be. In many ways, writing this story was more like a performance, and that’s how I approached it, and how I approach all my projects. I merely sit down and perform the story on the page, and the story does what it wants through me. At least in that first draft. Later I can use my more aware, editorial brain to clean up what I did, of course.

Guernica: There’s a lot of ego and authorship with some writers, but I don’t get that vibe from you at all.

Flores: When writing my previous book, Death to the Bullshit Artists of South Texas, I tried experimenting with this writing technique where I’d just try to remove myself and the reality of everything, and I learned to really follow stories toward wherever they led me. I realized I had a lot of fun writing this way, and Tears of the Trufflepig was the first time I tried to use this technique with a novel, which made the experience of writing it even more terrifying. I’d seriously wake up in the middle of the night in a panic during those three months, because I didn’t know what was going to happen next in the book. But then, after sitting down and forcing myself even to write that first word, what needed to happen next became so obvious.

Guernica: Like when E.L. Doctorow said, “Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” Wherever it was you were trying to go, I think you made it. I have to come back now to the little guy in the title, the Trufflepig. A tiny-eared pig with a bird’s beak and crocodile skin. How did you make us love such an ugly animal?

Flores: I am grateful to the Trufflepig. It’s my modest contribution to The Book of Imaginary Beings, South Texas-style.

Tears of the Trufflepig is available May 14, 2019 from MCD × FSGO.