“The House Republicans don’t seem to have noticed that today’s U.N. is not the U.N. of the 1970s when the Soviets and their pals could pass a resolution that the world was flat.”

—Thomas Friedman, 1995

The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century

—Thomas Friedman, 2005

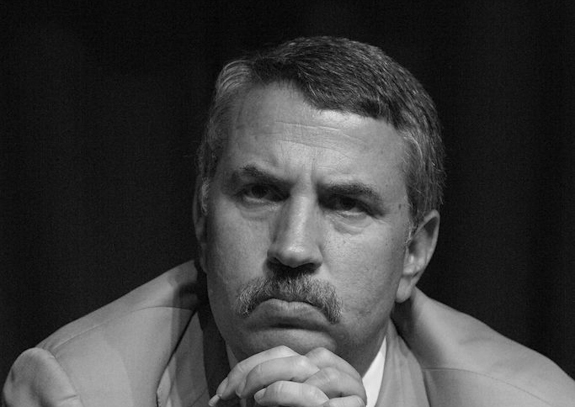

In the first chapter of his bestseller on globalization, The World Is Flat, three-time Pulitzer Prize–winning foreign affairs columnist for The New York Times Thomas Friedman suggests that his repertoire of achievements also includes being heir to Christopher Columbus. According to Friedman, he has followed in the footsteps of the fifteenth-century icon by making an unexpected discovery regarding the shape of the world during an encounter with “people called Indians.”

Friedman’s Indians reside in India proper, of course, not in the Caribbean, and include among their ranks CEO Nandan Nilekani of Infosys Technologies Limited in Bangalore, where Friedman has come in the early twenty-first century to investigate phenomena such as outsourcing and to exult over the globalization-era instructions he receives at the KGA Golf Club downtown: “Aim at either Microsoft or IBM.” Nilekani unwittingly plants the flat-world seed in Friedman’s mind by commenting, in reference to technological advancements enabling other countries to challenge presumed American hegemony in certain business sectors: “Tom, the playing field is being leveled.”

The Columbus-like discovery process culminates with Friedman’s conversion of one of the components of Nilekani’s idiomatic expression into a more convenient synonym: “What Nandan is saying, I thought to myself, is that the playing field is being flattened… Flattened? Flattened? I rolled that word around in my head for a while and then, in the chemical way that these things happen, it just popped out: My God, he’s telling me the world is flat!”

No compelling justification is ever provided for how a war against deterrables will solve the problem of undeterrables who by definition cannot be deterred.

The viability of the new metaphor has already been called into question by Friedman’s assessment two pages prior to the flat-world discovery that the Infosys campus is in fact “a different world,” given that the rest of India is not characterized by things like a “massive resort-size swimming pool” and a “fabulous health club.” No attention is meanwhile paid to the possibility that a normal, round earth—on which all circumferential points are equidistant from the center—might more effectively convey the notion of the global network Friedman maintains is increasingly equalizing human opportunity.

An array of disclaimers and metaphorical qualifications begins to surface around page 536, such that it ultimately appears that the book might have been more appropriately titled The World Is Sometimes Indefinitely Maybe Partially Flat—But Don’t Worry, I Know It’s Not, or perhaps The World Is Flat, Except for the Part That Is Un-Flat and the Twilight Zone Where Half-Flat People Live. As for his announcement that “unlike Columbus, I didn’t stop with India,” Friedman intends this as an affirmation of his continued exploration of various parts of the globe and not as an admission of his continuing tendency to err—which he does first and foremost by incorrectly attributing the discovery that the earth is round to the geographically misguided Italian voyager.

Leaving aside for the moment the blunders that plague Friedman’s writing, the comparison with Columbus is actually quite apt in other ways, as well. For instance, both characters might be accused of transmitting a similar brand of hubris, nurtured by their respective societies, according to which “the Other” is permitted existence only via the discoverer-hero himself. While Columbus is credited with enabling preexisting populations on the American continent to enter the realm of true existence by reporting them to European civilization, Friedman assumes responsibility for the earth’s inhabitants in general without literally having to encounter them.

As the world becomes ever more interconnected, Friedman appears to be under the impression that he is licensed to extrapolate observations of select demographic groups, such as Indian call center employees pleased with the opportunities provided them by U.S. corporations, and to issue pronouncements like the following on behalf of humanity: “Three United States are better than one, and five would be better than three.” Not surprisingly, Friedman does not respond favorably when elements of humanity fail to internalize the aspirations he has assigned them, resulting in anthropological revelations such as that one of the impediments to freedom in the Arab world is “the wall in the Arab mind.” Friedman explains in 2003 that “I hit my head against that wall” while conversing with Egyptian journalists who “could see nothing good coming from the U.S. ‘occupation’ of Iraq” and who are thus written off as proponents of “Saddamism.”

Friedman’s writing is characterized by a reduction of complex international phenomena to simplistic rhetoric and theorems that rarely withstand the test of reality.

Friedman initially hocks the possibility of a democratizing war on Iraq as “the most important task worth doing and worth debating,” based on a variety of fluctuating reasons, such as that “install[ing] a decent, tolerant, pluralistic, multi-religious government in Iraq… would be the best answer and antidote to both Saddam and Osama.” However, Friedman himself reiterates that the real threat to “open, Western, liberal societies today” consists not of “the deterrables, like Saddam, but the undeterrables—the boys who did 9/11, who hate us more than they love life. It’s these human missiles of mass destruction that could really destroy our open society.” No compelling justification is ever provided for how a war against deterrables whose weapons are not the problem will solve the problem of undeterrables who are the weapons and who by definition cannot be deterred anyway. As for Friedman’s speculation in a 1997 column that “Saddam Hussein is the reason God created cruise missiles,” this is not entirely reconcilable with his suggestion in the very same article that Saddam be eliminated via “a head shot”—not generally a setting on such weaponry.

Though he never disputes the idea that war on Iraq was a “legitimate choice,” Friedman gradually downgrades his war aims to “salvag[ing] something decent” in said country, while appearing to forget for varying stretches of time that the U.S. military is also still involved in a war in Afghanistan. Given the prominence of Friedman’s perch at The New York Times, from which he is permitted to promote—and to disguise as pedagogical in nature—bellicose projects resulting in over one million Iraqi deaths to date, it is not at all far-fetched to resurrect the comparison with Columbus in order to suggest that the designated heir is also complicit in the decimation of foreign populations standing in the way of civilization’s demands.

The foundations of Friedman’s journalistic education consist of a tenth-grade introductory course taught by Hattie M. Steinberg at St. Louis Park High School in a suburb of Minneapolis in 1969, after which Friedman claims to have “never needed, or taken, another course in journalism.” Following a BA from Brandeis University and an MPhil in Modern Middle East studies from Oxford, Friedman worked briefly for United Press International and was hired by The New York Times in 1981. He served as bureau chief in both Beirut and Jerusalem in the 1980s before becoming chief economic correspondent in the Washington bureau, and became the newspaper’s foreign affairs columnist in 1995. He has written six best-selling books, dealing variously with the Middle East, globalization, and the clean energy quest: From Beirut to Jerusalem (1989), The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization (1999), Longitudes and Attitudes: Exploring the World After September 11 (2002), The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century (2005), and Hot, Flat, and Crowded: Why We Need a Green Revolution—and How It Can Renew America (2008), and That Used to Be Us (2011).

Friedman’s writing is characterized by a reduction of complex international phenomena to simplistic rhetoric and theorems that rarely withstand the test of reality. His vacuous but much-publicized “First Law of Petropolitics”—which Friedman devises by plotting a handful of historical incidents on a napkin and which states that the price of oil is inversely related to the pace of freedom—does not even withstand the test of the very Freedom House reports that Friedman invokes as evidence in support of the alleged law. The tendency toward rampant reductionism has become such a Friedman trademark that one finds oneself wondering whether he is not intentionally parodying himself when he introduces “A Theory of Everything” to explain anti-American sentiment in the world and states his hope “that people will write in with comments or catcalls so I can continue to refine [the theory], turn it into a quick book and pay my daughter’s college tuition.”

In the case of Friedman’s musings on the Arab/Muslim world, the reduction process produces decontextualized and often patronizing or blatantly racist generalizations, such as that suicide bombing in Israel indicates a “collective madness” on the part of the Palestinians, whom Friedman has determined it is permissible to refer to collectively as “Ahmed.” Criticism of Israeli crimes is largely restricted to the issue of settlement-building; generalizations about the United States meanwhile often arrive in the form of observations along the lines of: “Is this a great country or what?” This does not mean, however, that the United States is not in perennial danger of descending into decisive non-greatness if it does not abide by Friedman’s diktats on oil dependence and other matters, such as the need to expand U.S. embassy libraries across the globe because “you’d be amazed at how many young people abroad had their first contact with America through an embassy library.”

Complementing his reductionist habit is Friedman’s insistence on imbuing trivial experiences abroad with undue or false significance, often in support of whatever “meta-story” he is peddling at the moment. The “tiny Vietnamese woman crouched on the sidewalk with her bathroom scale” in Hanoi in 1995, to whom Friedman gives a dollar to weigh himself each morning of his visit, thus becomes proof that “globalization emerges from below, from street level, from people’s very souls and from their very deepest aspirations.” The Pakistani youth wearing a jacket imprinted with the word “Titanic” on Friedman’s Emirates Air flight in 2001 becomes a sign that Pakistan is either the Titanic or the iceberg. The presence of pork chops at Friedman’s cousin Giora’s bar mitzvah in Israel prompts deep reflection: “I thought about the meaning of Giora’s pork chops for several days. They seemed to contain a larger message.”

A different metaphorical pile-up occurs when… readers are bombarded with an image of Kabul as a smashed cakelike Liberia-esque Ground Zero East covered with snow, ice, and aspects of Dresden, the Beirut Green Line, and Hiroshima.

Friedman begins The Lexus and the Olive Tree with a detailed recounting of a 1994 experience in a Tokyo hotel in which his room service request for four oranges results first in four glasses of orange juice and then in four peeled and diced oranges, all transported by a Japanese serviceperson unable to correctly pronounce the word “orange.” Only after almost two pages do we learn that the point of this citrus saga, plus another one in a Hanoi hotel dining room involving tangerines, is that Friedman “would find a lot of things on my plate and outside my door that I wasn’t planning to find as I traveled the globe for the Times.”

That these extensive travels have not produced a more relevant introductory anecdote to a book about globalization is curious, especially since Friedman boasts in Longitudes and Attitudes that he has “total freedom, and an almost unlimited budget, to explore,” and especially since he criticizes writers who eschew shoe-leather reporting in favor of “sitting at home in their pajamas firing off digital mortars.” It perhaps does not occur to our foreign affairs columnist that, in the era of online publications, most writers do not have access to the funds that would enable them to fire off digital mortars about the “Russian breakfast” option on the room service menu at the five-star Meliá Cohiba in Havana, or to arrive at conclusions regarding the root causes of poverty in Africa by going on safari in Botswana. It should be noted, however, that Friedman’s coverage of the Lebanese civil war and the first Palestinian Intifada—though often plagued by untruths as well—was more readily classifiable as shoe-leather reporting, perhaps because he did not define his job at the time as “tourist with an attitude.”

Friedman additionally reveals in Longitudes and Attitudes that the “only person who sees my two columns each week before they show up in the newspaper is a copy editor who edits them for grammar and spelling,” and that for the duration of his columnist career up to this point he has “never had a conversation with the publisher of The New York Times about any opinion I’ve adopted—before or after any column I’ve written.” It comes as no surprise, of course, that said publisher feels no need to rein in an employee whose last failure to toe the paper’s editorial line appears to have occurred in 1982, when Friedman’s reference to indiscriminate Israeli shelling of West Beirut launches a battle ultimately resulting in a $5,000 raise and an “emotional lunch” with Times executive editor A. M. (Abe) Rosenthal, who “threw his arms around me in a big Abe bear hug, told me all was forgiven and then whispered in my ear: ‘Now listen, you clever little !%#@: don’t you ever do that again.’” Friedman’s confirmed immunity from most kinds of editing meanwhile explains his continued ability to churn out incoherent metaphors, the terms of which he himself tends to lose track.

Consider, for example, his pre-Iraq war advice to George W. Bush to throw his steering wheel out the window in a vehicular game of chicken with Saddam Hussein, immediately followed by the warning that “if Saddam swerves aside by accepting unconditional [weapons] inspections,” the Bush team cannot “also swerve off the road, chase [Saddam’s] car and crash into it anyway”—an option that would seem to have been obviated by removal of the Bush team’s navigational instrument. A different sort of metaphorical pile-up occurs when Friedman visits Afghanistan, and readers are bombarded with an image of Kabul as a smashed cakelike Liberia-esque Ground Zero East covered with snow, ice, and aspects of Dresden, the Beirut Green Line, and Hiroshima.

Alas, the point of my new book on Friedman, from which this introduction is taken, is not to laugh at Friedman’s bungled metaphors, or the number of times he devises foreign policy prescriptions based on experiences in hotel rooms, restaurants, and airplanes. Rather, it is to demonstrate the defectiveness in form and in substance of his disjointed discourse, and in doing so offer a testament to the degenerate state of the mainstream media in the United States.

Friedman’s reporting is replete with hollow analyses (e.g., an American victory in Afghanistan is possible as long as it recognizes that “Dorothy, this ain’t Kansas”) and factual inaccuracies, ranging from the relatively trivial (Chile shares a border with Russia but Poland does not) to the sort of deliberate obfuscation of fact that is condoned by the establishment (the Palestinians were offered 95 percent of what they wanted at Camp David). Self-contradictions abound, and, two hundred pages into The World Is Flat, Friedman defines Globalization 1.0 as the era in which he was required to physically visit an airline ticket office in order to make his travel arrangements—whereas, according to the definition he provides at the start of the book, Globalization 1.0 ended around the year 1800.

As for contradictions in matters of greater geopolitical consequence, these include the aforementioned continuous adding and subtracting of motives for the Iraq war, which is alternately characterized as evidence of the moral clarity of the Bush administration, evidence of the U.S. military’s ability to make Iraqis “Suck. On. This,” and simultaneously a neoconservative project and “the most radical-liberal revolutionary war the U.S. has ever launched”—indicating that “the left needs to get beyond its opposition to the war and start pitching in with its own ideas and moral support to try to make lemons into lemonade in Baghdad.” The supremely liberal nature of the war is especially confounding given that Friedman also defines himself as “a liberal on every issue other than this war.”

Whatever era of globalization we are currently in, it is one in which news professionals are increasingly poised to influence the outcomes of the very world events they are reporting. Friedman’s contributions are not limited to Iraq, as is clear from the following passage from veteran British reporter Robert Fisk’s The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East:

“How many journalists encouraged the Israelis—by their reporting or by their willfully given, foolish advice—to undertake the brutal assaults on the Palestinians? On March 31, 2002—just three days before the assault on Jenin—Tom Friedman wrote in The New York Times that ‘Israel needs to deliver a military blow that clearly shows terror will not pay.’ Well, thanks, Tom, I said to myself when I read this piece of lethal journalism a few days later. The Israelis certainly followed Friedman’s advice.”

That Friedman discredits himself as a journalist by championing the killing of civilians has not prevented him from being hailed as a master of the trade, an objective commentator on the Middle East, and a foreign policy sage sought out by Barack Obama in times of international uncertainty (such as the 2011 Arab uprisings). Friedman appears as required reading on university syllabi and receives $75,000 for public speaking appearances. He occupies slot No. 33 on Foreign Policy’s Top 100 Global Thinkers of 2010, accompanied by the reminder that “Friedman doesn’t just report on events; he helps shape them”—despite minor setbacks such as the disastrous fate recently met by his thoughts on the Irish economy.

Friedman’s exceptionalism lies simply in the extent of his symbiosis with centers of power.

Friedman’s latest incarnation as award-winning conservationist has spawned a whole new level of irony as he has endeavored to reconcile this identity with preceding ones: “The neocon strategy may have been necessary to trigger reform in Iraq and the wider Arab world, but it will not be sufficient unless it is followed up by what I call a ‘geo-green’ strategy.” Readers may question how many true “geo-greens” would advocate the tactical contamination of the earth’s soil with depleted uranium munitions. Why not introduce a doctrine of neoconservationism?

A more critical question, of course, is how a journalist whose professional qualifications include rhetorical incoherence has nonetheless ascended to an internationally recognized position as media icon. (Friedman even suggests at one point that Osama bin Laden has been perusing his column.) Hardly a fluke, Friedman’s accumulation of influence is a direct result of his service as mouthpiece for empire and capital, i.e., as resident apologist for U.S. military excess and punishing economic policies.

Naturally, Friedman is far from alone when it comes to co-opted media figures providing a veneer of independent validation to state and corporate hegemonic endeavors in which they are entirely complicit. Friedman’s exceptionalism lies simply in the extent of his symbiosis with centers of power. Let us briefly reconsider the evolution of The World Is Flat, which begins with Friedman’s hobnobbing with the Infosys CEO in Bangalore.

A favorable profile of Friedman from a 2006 edition of The Washingtonian specifies that Friedman’s flat-world theory was developed in collaboration with the vice president of corporate strategy at IBM, and that—in addition to remaining on The New York Times bestseller list for over a year—the book “jump-started a national debate over American competitiveness that was picked up in President Bush’s State of the Union address.” An article from the Financial Times website the previous year meanwhile announces Friedman’s receipt of the first annual £30,000 Financial Times and Goldman Sachs Business Book of the Year Award for The World Is Flat; Friedman is quoted as repaying the compliment by declaring the Financial Times and Goldman Sachs “two such classy organizations, who take business and business reporting seriously. I’m thrilled and honored because the judges who made this award are such an esteemed group.”

Among the “esteemed” components of the “classy” Wall Street firm is executive Lloyd Blankfein, a member of the judge’s panel for Friedman’s award who, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial meltdown, reiterated his commitment to serious business by lying under oath to Congress about Goldman’s classy defrauding of clients. In an indispensable exposé for Rolling Stone, investigative journalist Matt Taibbi provides the following analogy about the firm’s self-enriching exploitation, “at the expense of society,” of the meltdown it helped to create:

“Goldman, to get $1.2 billion in crap off its books, dumps a huge lot of deadly mortgages on its clients, lies about where that crap came from and claims it believes in the product even as it’s betting $2 billion against it. When its victims try to run out of the burning house, Goldman stands in the doorway, blasts them all with gasoline before they can escape, and then has the balls to send a bill overcharging its victims for the pleasure of getting fried.”

Friedman, despite criticizing U.S. investment banks in 2008 for deviating from the corporate ethics set forth in his friend Dov Seidman’s book How: Why How We Do Anything Means Everything… in Business (and in Life), by bundling together risky mortgage bonds in order to “engineer money from money,” continues throughout 2008 and 2009 to quote Goldman Sachs executives and analysts on how the U.S. government should respond to the financial crisis—namely by throwing more billions at banks. It is not until 2010 that Friedman directly denounces Goldman as “the poster boy for banks behaving by ‘situational values’—exploiting whatever the situation, or rules that it helped to write, allowed.” Another Seidman concept, situational values are the opposite of “sustainable values” and are consistently decried by Friedman, who fails to explain how intermittent denunciation of Goldman Sachs is indicative of a sustainable value system. He meanwhile continues to campaign against entitlements and to encourage the slashing of corporate and payroll taxes, policies obviously not designed to punish the poster boy.

Aside from Blankfein, the judging panel for the 2005 FT-Goldman Sachs award also happens to include the Chairman and Chief Mentor of Infosys, star of The World Is Flat. Though £30,000 may be an insignificant sum for a character who accumulates at least seven figures of annual income on top of having married into one of the hundred wealthiest families in the United States, the award is a useful example of the potentially incestuous nature of the relationship between businesses and business reporters. The process of mutual aggrandizement in this case is straightforward: Friedman writes book about globalization under guidance of corporate executives, corporate executives hail book as ingenious blueprint for world, accolades propel Friedman’s fame, Friedman exploits fame to further reinforce elite power structures while occasionally attributing his project to more sentimental motivations such as those cited in The World Is Flat:

“When done right and in a sustained manner, globalization has a huge potential to lift large numbers of people out of poverty. And when I see large numbers of people escaping poverty in places like India, China, or Ireland, well, yes, I get a little emotional.”

As for Friedman’s genuine motivations, he regularly advertises his subscription to billionaire investor Warren Buffett’s theory that everything he has achieved in life is a result of having been born in the United States, and reiterates his duty to pass his situation on to his children. Given that the overwhelming majority of offspring produced in the United States—not to mention the world—cannot aspire to situations that involve belonging to one of the country’s hundred richest families, it goes without saying that Friedman fully endorses the perpetuation of a system of institutionalized economic inequality.

As he himself notes in The Lexus and the Olive Tree with regard to the “Darwinian brutality” of free-market capitalism: “Other systems may be able to distribute and divide income more efficiently and equitably, but none can generate income to distribute as efficiently.” Friedman’s tendency to convert victims of imposed economic systems into victims of natural selection is symptomatic of his categorical dismissal of the realities affecting the global poor (see, for example, his response to Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph Stiglitz’s observation in 2006 that “The number of people living in poverty in Africa in the last 20 years has doubled” with the statement: “But India matters”). Such tendencies are meanwhile rendered all the more grating by Friedman’s occasional assumption of the role of capitalist victim himself, as in the following scenario from 1998:

“While waiting to see if the U.N. Secretary General’s eleventh-hour visit to Iraq can avert a war, I sought some diversion by catching up on the sports news. Talk about depressing. If you want to see how the other great superpower at work in the world today—the unfettered markets—is reshaping our lives and uprooting communities, turn to sports.”

The superior depressiveness in this case is in part a result of adverse effects of unfettered markets on Friedman’s NBA season tickets, such as that “teams are being forced to trade away high-priced stars left and right.”

“Ten years from now, will an institution like Thomas Friedman be possible?”

Friedman’s prophecies and directives do not all emerge from the depths of corporate libido. He is also equipped with a “brain trust,” a group of academics, experts, and rabbis with predictable views who are personal friends of Friedman and are quoted so regularly at times that one finds oneself wondering, for example, if Johns Hopkins professor Michael Mandelbaum, Middle East expert Stephen P. Cohen, and Israeli political theorist Yaron Ezrahi might not be nominated honorary New York Times columnists. Mandelbaum and Cohen also share the distinction of being Friedman’s “soul mates and constant intellectual companions,” while Cohen is graced with the additional denomination “soul brother.”

As late Palestinian American scholar Edward Said notes in his 1989 essay “The Orientalist Express: Thomas Friedman Wraps Up the Middle East”—in reference to Friedman’s blissful reductions of Arabo-Islamic peoples in From Beirut to Jerusalem—Friedman “palms off his opinions (and those of his sources) as reasonable, uncontested, secure. In fact they are minority views and have been under severe attack for several decades now.” Other passages from Said’s essay are useful for comprehending the triumph of the persona of Thomas Friedman on the journalistic stage:

“It is not just the comic philistinism of Friedman’s ideas that I find so remarkably jejune, or his sassy and unbeguiling manner… It is rather the special combination of disarming incoherence and unearned egoism that gives him his cockily alarming plausibility—qualities that may explain [From Beirut to Jerusalem]’s startling commercial success. It’s as if… what scholars, poets, historians, fighters, and statesmen have done is not as important or as central as what Friedman himself thinks.”

As for what happens when Friedman himself thinks that Iraqis should “Suck. On. This” as compensation for 9/11, we can only assume that haughty refrains of sexual-military domination find resonance among audiences seeking to defy feelings of individual and/or national inadequacy. It is meanwhile not clear why Friedman subsequently purports to be scandalized by the sexual military goings-on at Abu Ghraib.

Regarding the future of the Friedman phenomenon, a television anchor from Israel’s Channel 2 informs him during a 2010 interview that he is an “endangered species” and poses the question: “Ten years from now, will an institution like Thomas Friedman be possible?” She is referring not to the possibility that by the year 2020 journalists who assign “moral clarity” to George W. Bush will no longer receive Pulitzer Prizes for “clarity of vision,” but rather to current trends away from print media.

Friedman laughs and suggests that the substance of his work will ensure his continued relevance. But you never know. After all, as Friedman himself has reasoned, it would be crazy to pay a lot of money for a belt if you already have suspenders, “especially if that belt makes it more likely your pants will fall down.”

This excerpt is from The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work.

Copyright © Belén Fernández 2011

Published by Verso Books.

Reprinted here with permission.