Library image number: 122450.

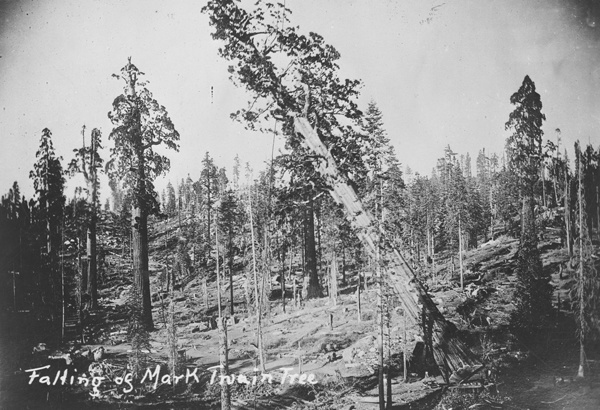

In the fall of 1891, Samuel David Dill wrote a letter to his boss. “I saw Mr. Moore he says he will go right to work and cut the specimen and have it hauled out,” he wrote. “He will have to get a saw made to order about 23 feet long.” In the accompanying photo the tree hangs at a fifty-degree angle, felled but still falling. The land around it is mostly cleared already, just a couple other giants remaining in the coppiced wood. Two men, employees of the lumber barons Austin D. Moore and Hiram T. Smith, stand beside the stump, watching eight days of hard work come crashing down.

Dill was a collector for the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The Mark Twain Tree, as that giant sequoia was known, “was of magnificent proportions, one of the most perfect trees in the grove,” wrote George H. Sherwood in a 1902 piece for the museum, “symmetrical, fully 300 feet tall, and entirely free of limbs for nearly 200 feet.” Moore and Smith donated the tree, and the museum covered the cost of labor and transport. Once they’d felled the sequoia, lumberjacks cut a four-foot-thick section of its trunk, then split it into pieces. They loaded the pieces onto wagons to get them down from the Sierra Nevadas, then put them on train cars for the journey cross-country.

Library image number: 42131.

Another segment of the tree was eventually sent to the Natural History Museum in London, where it sits like an altarpiece at the top of a flight of stairs at one end of the main hall. The reassembled section is an almost perfect circle more than sixteen feet across, measured inside the foot-thick bark. Visitors stand far back, trying to get a full view, or move in close to peer over the railing at its close-packed rings. The tree is annotated in small white letters matching dates and events to the years of its life—1850: Darwin publishes The Origin of Species; 1500: Leonardo da Vinci invents flying machine; 1000: Leif Ericsson reaches North America; 600: Start of Islam; 557: Our sequoia is a seedling. The tree was 1,341 years old when it was felled, which, as Dr. Karen Wonders has noted in a piece on logging big trees, makes it a contemporary of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian.

The ancient trees always seem to inspire this measuring of their lives against ours. Though the comparison brings no real clarity to either the life of the tree or that of Justinian, we are impressed. We are staggered by the sequoias’ age as well as by their size. Cumulonimbus greenery billows from red-orange bole, tall as three blue whales laid fluke to prow; there is nothing as big as a sequoia and never was, and few things as old. In a world full of brevity and smallness, size and age are valuable. But it’s hard to say what they are worth.

If that were the end of the story, we would find it familiar: it is the story of our bigger past, when there was more space for wild things.

Encountering the trees in the mid-1800s, early Euro-American settlers’ first impulse was to cut them down. As Richard J. Hartesveldt wrote in a chapter on logging in the National Park Service’s The Giant Sequoia of the Sierra Nevada, “The thought that a single sequoia log contained more board footage than a whole acre of northern pine held, for a Lake States logger, a pocket-jingling interest.” Board feet are easily put into dollars; they’re of a more human scale. The intangible is outweighed by the tangible, the past and the future outweighed by the now. If that were the end of the story, we would find it familiar: it is the story of our bigger past, when there was more space for wild things, when there were Rocky Mountain grasshoppers and bison and passenger pigeons, when the Colorado was unbound and grizzly bears still wandered California.

From the beginning, though, many people recognized the trees’ intangible values, and fought to stop the destruction. The Scottish naturalist John Muir was foremost among them. After he died in 1914, a draft of an essay titled “Save the Redwoods” was found in his papers (“redwoods” serving for both the sequoias and their coastal cousins). Several sequoia groves were by then under federal or state protection, but many more were still in danger. In the piece, he pleaded for their protection, tallying what had been lost since his first visits to the Sierra Nevadas decades earlier, and what he expected still to be lost.

Although 100 years later the sequoias are safe from the axe, they are still not safe in a bigger sense. A long focus on simply guarding the trees only sets them up for a more devastating destruction. For decades, settlers and then grove managers stopped the low-burning fires that for millennia had regularly swept through the groves. Scientists now know that the fires were crucial to the vitality of the groves: they cleared brush without harming the fire-resistant sequoias, fertilized the soil, and killed fungi and other pathogens. Most importantly, the heat opened up the cones in the sequoias’ boughs, scattering the new clearings with their seed. Without regular fires, the sequoias’ shade-tolerant rivals grew up, creating fuel ladders into the canopy, and starving out sequoia seedlings. Many groves remain clotted, in a sort of suspended animation, vulnerable to catastrophic fires, their seedlings withering. This story, too, is familiar: it is the story of best intentions mislaid; of the cat that was meant to eat the rat, but ate only songbirds. Surveying the empty nests, it is hard to appreciate the original gesture.

Lately, the sequoias’ situation is even more tenuous. California’s current drought gives one vision of the future Sierra Nevada—warmer and drier. Already the trees are showing signs of stress. They’re self-pruning, shedding needles to conserve water. They’re not in danger yet, but scientists worry that if drought comes more frequently and for longer, as they predict it will, the trees will eventually die. This story is perhaps the most familiar of all: it is the story of our constantly shrinking future, where Glacier National Park has no glaciers and Joshua Tree National Park no Joshua trees. We gird ourselves for it, wondering how it will be when the Joshua trees wither and the glaciers melt, when it is hotter and drier and the sequoias die; in every case, it is hard not to wonder whether we will be forgiven.

While one ending is averted, another story begins. California’s largest timber company has begun planting sequoia seedlings in new groves scattered across its holdings, many of them hundreds of miles north of the sequoias’ natural range, where the climate is cooler and wetter, and hopefully the trees will be able to survive far into the future. The company calls it a “genetic conservation program.” There are reasons to be cynical about the company’s motivations, reasons also to suspect that trying to save the trees is as much an act of hubris as was cutting them down. But there are also reasons to think—to hope—that the seedlings will grow big and old, that this effort to save them and all the rest aren’t really in vain. A seedling is nothing but a possibility, and perhaps this story will turn out the same as all the rest. But that ending will be for another time.

Sequoiadendron giganteum, the species, is not in danger of extinction. Even in Muir’s day, seed collectors scoured the groves, hauling away bags of cones. Today giant sequoias grow from Scotland to Turkey to Australia. The species is safe, but it’s the safety of pandas in zoos. What’s special about the sequoias is not so much the individual trees as their collective effect. The groves are often compared, aptly, to cathedrals—open, echoing, high-ceilinged spaces, weighted with a sense of the eternal.

A crew of ecologists and foresters from the US Geological Survey hike through Sequoia National Park, pushing a path through the snow of winter’s first storm. They’re shaded by sugar pines, firs, and cedars, all of them dwarfed by the red-boned sequoias. This grove, the Giant Forest, is sparse and clean, resembling in the most important ways its condition before the arrival of Euro-Americans. Foresters here in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks have been intentionally lighting fires since the 1960s, but controlled burning is difficult, expensive, and often misunderstood by a public generally less concerned with the overall health of the forest and more with the individual, iconic trees.

The sequoias here are now self-pruning as a defense against California’s ongoing drought. Two members of the field crew stop to examine the crown of each of the big trees, gauging what fraction has browned, entering the figures in a palm-sized computer. With the data, the foresters hope to establish a baseline, which could be used for comparison if the trees lose their needles again.

“You see this really bad one?” one of them says, pointing as the crown of an old sequoia comes into view around a bend.

“Wow,” says Nate Stephenson, the group’s leader. Along with two members of his field crew, for whom this is a routine hike, Stephenson is joined by another forester and two office administrators. More snow is coming, and this could be the last chance for a field trip. “Wow!” he says again. The tree’s bark is rust-red, furrowed up and down, pocked with woodpecker holes and scars from fire. At its blackened base, the tree opens to reveal a deep hollow. The crack tapers closed, as though the tree is zippered together from the top. Its bark is layered like shale, grown over in places with yellow-green lichen. In other places bare wood is exposed, charred black and the texture of cracked dry mud. Into it someone has carved a five-pointed star. The snow beneath the tree is carpeted with golden-brown needles, each a cluster of cricked fingers with overlapping scales like birds’ legs. Stephenson peers at its crown, two hundred feet up, flecks of deep green amid the golden-brown. Maybe it was girdled during the last fire, leaving it vulnerable, he says. “It’s probably going to die.”

For thousands of years, predicting the groves’ condition from one century to the next would have been easy. To predict their condition even fifty years from now is impossible.

Whether you take the dead needles as a dire warning or not depends on your point of view. By the scale of Stephenson’s experience, the dying needles are unprecedented, at the very least. He’s worked in the park since the late 1970s. “Some of them have reached the point where they’re pretty darn stressed, and I’ve never seen that in my entire career,” he says. “I’ve looked back in the old written records, and talked to the old-timers, they’ve never seen it.” Stephenson says that nearly everything else about the park has remained much the same since well before his arrival; the dying needles are something new.

This impression of steadiness, though, disappears when you take a longer view. Measured against the life of a sequoia, the last 150 years have brought chaotic change to the groves. Now, even as the groves’ human minders work to remedy the errors of their predecessors, climate change threatens the long-term survival of the native groves. To put it another way, for thousands of years, predicting the groves’ condition from one century to the next would have been easy. To predict their condition even fifty years from now is impossible.

By the longer view, such periods of turmoil are regular, and the species appears not stolid, but migratory. Fossils of a species very similar to the sequoias can be found across Europe and North America, and as far away as Australia and New Zealand. Some of them are 200 million years old. Modern sequoias probably crossed the Sierras just as the mountains were rising, eventually receding to their narrow plot of its western slopes. Looking at the trees from this longer perspective, many, Muir among them, have called the sequoias the last few of a once-great race, doomed to extinction long before the arrival of Euro-Americans.

Stephenson says the sequoia forest here is only a couple generations old. By analyzing the pollen in layers of sediment, scientists are able to tell that, starting around 10,000 years ago, a warmer climate killed the sequoias off everywhere except at the edges of streams, pushing them close to extinction. Around 4,500 years ago, the climate became cooler and wetter, allowing the trees to expand to their current range. The trees can live at least 3,200 years, so the oldest ones alive today are the offspring of those that first recolonized this area, he says. This grove, measured in this way, is almost new.

Although the most vulnerable among them may die, most of these sequoias will probably survive the current drought, Stephenson says. Even assuming that intervals of drought in the region do grow more frequent and longer, we don’t yet know what the trees are capable of weathering. In the short term, it’s conceivable—probable even—that grove managers will decide to water their groves. Managers have already floated the idea. That might be sufficient for a few generations, but it’s a stopgap. Probably the best long-term solution would be to expand the trees’ range, something unlikely to be accomplished without human intervention, since many of the sequoia groves are currently barely reproducing. Assuming their present range becomes hotter and drier, it would make sense to expand their range into some place likely to be cooler and wetter—by our current best guess, somewhere north. Over the millennia, sequoias have thrived far north of their present range. In a certain sense, planting them in Northern California would be a reintroduction.

The tree alone remains, living now much as it did then. A sequoia sprouting today is similarly solitary, heading far into the future without us.

But even assuming that the sequoias will require human intervention for long-term survival, and that migration to a cooler, wetter climate is the best course of action, brings us to a puzzle: the sequoias will probably be okay during our lifetimes, and those of our kids and grandkids. For which generation are we trying to save them? Are we really culpable for their current situation, or were they doomed to extinction millennia before our arrival on the scene? Are we thinking on the trees’ scale or our own?

“Monarchs of monarchs,” Muir called the sequoias in Harper’s magazine, trees of “godlike grandeur” and “giant loveliness.” He marveled at their size, recalling a dance floor he’d seen made from a single tree’s stump, and at their endurance. “I never saw a Big Tree that had died a natural death,” he wrote. “Barring accidents, they seem to be immortal.” The world that an old sequoia occupied as a seedling is lost, the people who lived there alive to us only through the artifacts and words and names they left behind. The tree alone remains, living now much as it did then. A sequoia sprouting today is similarly solitary, heading far into the future without us. Muir was right, in that way—theirs seems a different kind of mortality.

The Dutch economist Kees van der Heijden wrote in a 1997 paper, “Scenarios, Strategies and the Strategy Process,” that most of what we know about the future is due to inertia—an object in motion tends to stay in motion, an object at rest tends to stay at rest. A tree today will likely be a tree tomorrow, a forest today will likely be a forest tomorrow. But our world is full of unbalanced forces—fire and landslides and men with crosscut saws. Inertia is quickly lost or gained. A few days further into the future, and a tree might as easily be fence stakes or matchsticks. The trees really live just the same as we do, day by day.

So the future is uncertain—obvious enough. But that also means that the trees can never truly be saved in any permanent way. Saving the trees in Muir’s day only delayed their doom. Restoring fire and attempting to bring the groves back to their pre-Euro-American condition also won’t be a permanent solution, if drought grows longer and more frequent. But it makes more sense to look at the sequence in reverse: saving the trees from the axe made saving them now possible, as saving them now will make it possible for them to be saved again by future generations.

We celebrate Muir for helping found the Sierra Club, for his advocacy of the national park system, for tirelessly trying to save natural spaces. The future cannot be imagined, of course, but he tried, and in imagining people who, like him, would appreciate wild things, who would value the big and old along with the quick and small, he in some way succeeded. He imagined us.

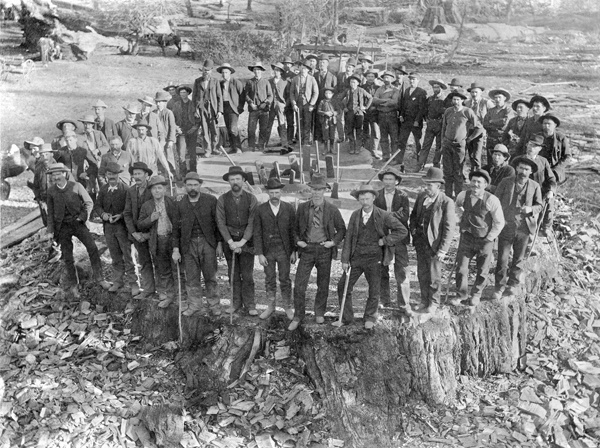

In another photo, twenty-five men and two boys are arranged in rows across the cut face of the Mark Twain Tree, standing on hammered-in pegs. They look like hunters beside their kill. The men wear vests and ties, hats and kerchiefs, and hold double-bit axes and rifles. With crossed arms, hands on hips, thumbs hooked into pockets, they are unsmiling, unconcerned, even defiant. More than anything, these men and the mill owners who hired them look shortsighted, craven in their failure to understand or care what the trees meant or would come to mean. They felled the immortals and thought of a future very near to them. But prescience is rare. They have become nearly as unreal to us as we were to them. They are anonymous, and in their anonymity, we do not blame them.

Glenn Lunak has a neatly trimmed gray mustache and a flannel tucked into his forest-green pants, and speaks with a slight Midwestern accent. He is the holotype of a forester. Lunak, the tree improvement manager for Sierra Pacific Industries, is driving high in the hills above Chico, in Northern California. Sierra Pacific is a third-generation, family-owned timber company. It’s the biggest timber company in California, and is one of the largest private landowners in the United States.

Over the next eighty or 100 years, in patches of about eighteen acres, Sierra Pacific will clear-cut more than half its holdings, or nearly a million acres. To call it tree farming “takes the romance out of it,” Lunak says, but that’s essentially what it is. By clear-cutting, replanting with a mix of native species, and periodically thinning to maximize growth rates, the foresters are able to harvest exponentially more board feet per acre than they could using the traditional “hunt and peck” method of periodically finding and harvesting just the most attractive trees in a natural forest, then allowing it to grow back in. Each clear-cut and replanted plot is thinned about fifteen or twenty years in, and then the remainder of the trees are harvested when they’re between eighty and 100 years old.

Environmentalists were outraged when the company announced the plan in the early 2000s. Clear-cutting destroys habitat for wildlife and causes runoff, they argued (and still argue), and Sierra Pacific uses herbicide to prevent the growth of weeds that would compete with its trees for water when it replants. It typically plants a mix of five species of pine and fir, which environmentalists describe as a monoculture compared to the hundreds of species of hardwoods, shrubs, grasses, and flowers that might populate a natural forest. “Conversion,” as Sierra Pacific calls it, looks bad, too, especially viewed from somewhere far off, like a helicopter or a satellite. The clear-cuts look like mange, everything good stripped off and hauled away.

The true nature of what is being passed on won’t be clear for many years.

Looking at a clear-cut, what is maybe most difficult is to imagine it as a forest. Nothing about the debris and exposed dirt suggests it. But, adopting Sierra Pacific’s longer perspective, it can be viewed as a freshly plowed field. Using data on the growth rates of its different crop species, combined with soil conditions, precipitation, elevation, and other information, the company is able to estimate how many board feet it will grow per acre over time. Although individual acres may be destroyed by disease or wind or fire, over thousands of acres and millions of trees, the company can be confident in what it is passing on for its next generation to harvest.

As the tree improvement manager, Lunak’s job is to find and breed the best-adapted individuals of each of the species the company grows, gradually creating straighter, healthier, faster-growing trees. From beginning to end, the process of choosing good breed stock, breeding, and replanting a better-adapted tree can take ten or fifteen years, he says. The company has been involved in tree breeding since the 1980s, in partnership with the Forest Service and other industry members. Lunak says, a few decades in, it’s already possible to judge his success. The full measure of his work won’t be apparent, though, until the trees are harvested and can be compared over their full lifespan. As with a clear-cut viewed too soon after the harvest or from too far away, the true nature of what is being passed on won’t be clear for many years.

Lunak drives from pavement to red dirt roads behind a locked gate, stopping once to wait while a worker in gray camo pants moves his bulldozer from the middle of the road. A beagle sits among the pedals at his feet, watching Lunak go by. He passes a clearing growing in with neat rows of Christmas-tree-sized seedlings, then into dense evergreen forest, blackberry vines creeping from the margins.

Back in 1980, Lunak says, when he was the replanting manager for this district, the state nursery had some giant sequoia seedlings. “I think I bought 500 giant sequoia seedlings, planted them just to see how well they would do,” he says. “It’s been years since I’ve driven back here.” He pulls into a clearing and hops out. Lunak looks around, taking in two decades of change. Though this is a conversion plot, clear-cut and replanted, the woods look almost natural, a mix of pines and firs and cedars, plus the sequoias. The trees are seventy, eighty feet tall, many of them with trunks more than two feet wide. “This is pretty cool,” he says. “This is way cool!” He laughs. He wanders into the woods, snapping over dead lower branches. He stops at a sequoia growing on a slope. The tree’s bark is lighter than that of the old sequoias, the corrugations in its bark more regular. Its canopy tapers neatly in a perfect Christmas-tree form, a spearhead reaching to the sky. “It’s only thirty-four years old,” he says. “I guess they’re growing pretty good, by God!”

“Maybe we’ll call it the Glenn Lunak Retirement Grove,” says John Hawkins, who manages replanting in the area, and they laugh.

“I’m gonna come out here next year after you thin it,” Lunak says to Hawkins. “It’s going to be so cool, it’ll be like a park.” What was unreal is made real, board feet made into something more.

In his 1986 book Under Whose Shade, Wesley Henderson wrote that on his high school graduation day, father Nelson Henderson, a second-generation farmer in Manitoba’s Swan River Valley, said to him, “The true meaning of life, Wesley, is to plant trees under whose shade you do not expect to sit.” On the way into the grove, Lunak had quoted Henderson—“and I take that to heart,” he’d said. Now, as he drives out, Lunak is quiet. The woods on either side are tall. Sunlight flickers through the shade.

Lunak stops next on a dirt road traversing a hillside. He and his companions lean against the truck, eating sandwiches for lunch. From up the road comes the sound of an engine, someone on a four-wheeler. Hawkins steps around the truck and holds up his hand. The driver stops. He pulls off his helmet, and they recognize him as a company biologist—he’s been out in the woods trying to trap fishers, but all he got was gray foxes.

It could be that if, in 100 years, Glenn Lunak is remembered, he will be remembered for his plan to save the sequoias. This is the cathedral.

“So, there’s giant sequoias here,” he says. “Did you guys plant them?” The foresters laugh, tell him yes.

“Huh, pretty cool,” he says. He puts his helmet back on and drives away. On the uphill side of the road is a natural forest, thinned but never fully cleared. Below is “Mountain Hollow Unit,” a conversion plot, recently clear-cut and replanted. A large tanoak stands alone in the middle of the plot, oddly reminiscent of the picture of the Mark Twain Tree. It was spared to provide a little habitat for wildlife and to soften the visual impact of the clear-cut. The clear-cut around it is stubbled with Ponderosa pine, incense cedar, Douglas fir, and species Sierra Pacific didn’t want but that grew anyway, bull thistle and Manzanita and nutmeg. Scattered among them are several hundred sequoia seedlings. It could be that if, in 100 years, Glenn Lunak is remembered, he will be remembered not so much for his work improving the genetics of Sierra Pacific’s breed stock, but for his plan to save the sequoias. This is the cathedral.

Lunak’s boss first came up with the idea at a conference on giant sequoias, but Lunak is in charge of planning and implementing the program. In 2010, the company started collecting cones from sequoia groves. Lunak says it aims to collect seeds from groves each year, waiting for storms to knock down fresh cones. A nursery sprouts and grows the seedlings, 20,000 or so from each grove. In many areas across the company’s holdings, previous owners planted sequoias as an experiment or out of curiosity, as Lunak did in the 1980s. These trees have allowed him to evaluate areas where the new groves can be expected to do well. The trees grow naturally only between about 4,000 and 7,000 feet of elevation, and always mixed with sugar pine. Roughly hewing to those criteria, Sierra Pacific plants the seedlings in a mix with native species, between 20 to 40 percent of the total, creating more than a dozen new groves per original grove, each bearing the full genetic diversity of its parent community. “What is the climate going to be doing fifty, 100, 200, 500 years from now?” Lunak says. “By replicating these grove representatives in numerous growing environments, we know some won’t do well, but by growing across this range of environments, we feel we will be successful in preserving the genetics of these groves over the long term.” Eventually, if all goes to plan, there will be more than 1,600 of these groves spread across the northern Sierra Nevada and southern Cascades, covering some 32,000 acres, compared to the roughly 47,000 acres of natural sequoia groves. As the company thins and harvests other trees, it will favor the sequoias, Lunak says, leaving them to grow fat and old.

As part of its agreement to collect cones on federal and state-managed groves, the company has pledged not to sell the sequoias it grows from those cones as timber, though there are indirect ways it could recoup its investment. Once they’re big enough, the groves could be entered into California’s carbon credit market, and someday they could maybe even be sold to the public as conservation easements, or parks. They could also be used as breed stock. Several years ago, Lunak conducted a study of the scattered sequoias that previous owners had planted across the company’s holdings, comparing them to nearby Ponderosa pines of similar age. In all but the most marginal ground, sequoias outperformed the pines in both diameter and height. Dr. Bill Libby, a geneticist specializing in sequoias, told me he thinks that under the right conditions, sequoias could have timber quality comparable to coast redwood, and could grow faster than any other species.

Dan Tomascheski, a vice president at Sierra Pacific, said that since they started the program in 2010, it’s cost roughly $150,000, not including the time that Lunak has spent on it. It’s not much money for a company whose founder is worth $3.6 billion, according to Forbes (company earnings aren’t available, as it is privately held). Both Tomaschescki and Lunak insist the program is purely altruistic. People outside the company who helped with the planning told me, though, that Sierra Pacific intends to make its money back, one way or another, although they believe the program is generally well intentioned. That a broad range of grove managers has agreed to allow Sierra Pacific to collect cones is also telling.

Of course, a single company can do bad as well as good; more than one environmentalist I spoke with about the program called it green washing, a public relations move, and it might be that. “I used ‘disingenuous,’ because I work directly with Sierra Pacific Industry folks in forest collaboratives,” John Buckley told me when I asked him over the phone how he would characterize Sierra Pacific Industries. “I think there’s a difference between calling someone a hypocrite and calling them disingenuous.” Buckley is a member of the Sierra Club and founder of the Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center, a Tuolumne County environmental nonprofit. Sierra Pacific’s supposed concern about climate change and its effect on giant sequoias is, at the very least, he said, at odds with what he’s seen from the company over the years. “They’ve consistently derided and denigrated those who have put forward the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” he said. Buckley was a wildland firefighter and Forest Service employee before he started the nonprofit twenty-five years ago. He said he disagrees deeply with Sierra Pacific’s clear-cutting practices, although he called it a “competent and professional tree-farming company.”

Lunak walks down the slope and stops in front of a sequoia. Its trunk is lavender, two inches wide at the base, its boughs four feet wide and four high. “Three years’ growth and look at that sucker,” Lunak says. But it doesn’t look like much, not yet. It’s still only a possibility. If and when these saplings grow to trees, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000 years from now, will people know their story? Will they recognize that they were deliberately planted? What language will those people speak? What world will they live in? And the trees themselves—will they take on the characteristics of natural groves, with snow covering them every winter and regular fires burning through to keep them healthy? Perhaps the grove in Sequoia National Park will be gone then, gone like the glaciers of Glacier National Park and the bears of the Californian flag. I ask Lunak and the others what they think this place will look like in 500 years. In a progress report the company released soon after my visit, Lunak wrote that in 160 years—or roughly the time required to grow, harvest, and replant the surrounding pine and firs twice—the sequoias could be between 170 and 240 feet tall, and between eight and ten feet in diameter. After the third rotation, at roughly 240 years, he wrote, the biggest of them would have swelled to nearly twelve feet across. But this day, looking out over the seedlings, he seems unsure how to answer. “Well, I can imagine that one at thirty-four years old,” Lunak says—the exact age of the trees we’d visited just an hour before. “Trunk diameter will be between twenty-four and thirty inches.” It is difficult even to speculate. Wherever these seedlings go, they go alone.

Muir’s house in Martinez is a blocky white Victorian, with thick columns and red trim and turquoise under the eaves. The land, just a handful of acres remaining from what was once a sprawling orchard, is scattered with olives and palm, pomegranate, rows of apple and pear and peach and grapes, all surrounded by a high fence. The parking lot and Park Service building at the east edge butts up against one of Martinez’s main roads. A graffiti-covered rail bridge and a highway pass along the southern edge. From the bell tower you can see both a large solar grid and a refinery to the north. Across the street is a yellow and teal Valero station. Tourists wander the grounds, snapping photos. The house is now a national monument.

AD 15,000 is the same as eternity, millions of uncertain days. Nothing of it can be known, not of the people nor of the trees.

In 1876, John Muir wrote an article on sequoias for the Sacramento Daily Union. “Judging from its present condition and its ancient history, as far as I have been able to decipher it,” he wrote, “our sequoia will live and flourish gloriously until A.D. 15,000 at least—probably for longer—that is, if it be allowed to remain in the hands of Nature.” AD 15,000 is the same as eternity, millions of uncertain days. Nothing of it can be known, not of the people nor of the trees. Looking forward, though, it seems unlikely that simply allowing the trees to remain in the hands of nature will be enough.

Much before then, the success or failure of our efforts to save the original cathedral groves will be clear, and also the success or failure of Sierra Pacific’s program. Perhaps in 500 years only the new groves will remain. Perhaps people will walk among them, traveling from around the world for a glimpse of immortality. Just as likely, the trees will have fallen to wind, flood, lightning, or any of the other myriad accidents that can kill a living thing. Maybe they’ll have been cut down for shingles. Maybe the program will have even somehow made things worse. Maybe the sequoias of Scotland and Australia and Turkey will have slipped their bounds and come to appear natural, or maybe climate change in California won’t mean what it did. Sierra Pacific may well be saving the sequoias, but this is probably not the last time they’ll need saving.

Muir’s tree is to the west of the house. He brought the sequoia seedling back from a trip to the Sierra Nevadas in the early 1880s. The tree is stunted, only a little taller than the sequoias Glenn Lunak planted in the 1980s. It tapers rapidly to a spindly crown, and its trunk bears long, weepy indentations, as though it’s collapsing inward. The tree is dying of a fungus, and probably has been since Muir planted it. Bill Libby, the geneticist, told me that every sequoia below 750 feet of elevation gets it. Planting them this low, Libby said, is “practically a death sentence.”

Chances are that Muir noticed the tree wasn’t thriving, said Keith Park, the arborist who looks after the tree—he may even have guessed before he planted it that it wouldn’t do well. “It’s limped along for many decades, and may limp along for many decades more,” he told me when I talked to him on the phone. Still, the canker rot is ultimately fatal. Park said he wanted to preserve the tree for posterity, to keep alive this connection to John Muir. He took cuttings from the tree, and a cloning company has managed to grow some seedlings. They should be big enough to plant next year, although he’s not sure yet where they’ll go, he said. Maybe back to the mountains. To flourish gloriously, to AD 15,000