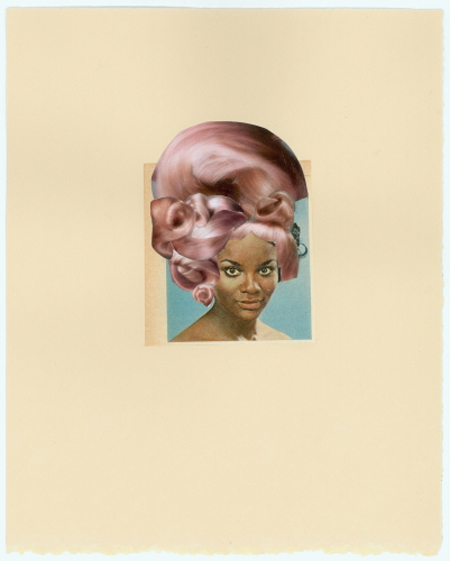

Courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

Mother raises those plucked, deep-toned eyebrows that did such excellent expressive work for women in the 1950s. Lift the penciled arch by three to four millimeters for bemused doubt, blatant disdain, or disapproval just playful enough to lure the speaker into more error. Mother’s lips form a small, cool smile that mirrors her eyebrow arch. She places a small, emphatic space between each word: Are. We. Rich? Then she adds, with a hint of weariness: Why do you ask?

I ask because I had been told that day. Your family must be rich. A schoolmate had told me and I’d faltered, with no answer, flattered and ashamed to be. We were supposed to eschew petty snobberies at the University of Chicago Laboratory School: intellectual superiority was our task. Other fathers were doctors. Other mothers dressed well and drove stylish cars. Wondering what had stirred that question left me anxious and a little queasy.

Mother says: We are not rich. And it’s impolite to ask anyone that question. Remember that. If you’re asked again, you should just say, ‘We’re comfortable.’ I take her words in and push on, because my classmate had asked a second question.

Are we upper class?

Mother’s eyebrows settle now. She sits back in the den chair and pauses for effect. I am about to receive general instruction in the liturgies of race and class.

We’re considered upper-class Negroes and upper-middle-class Americans, Mother says. But of course most people would like to consider us Just More Negroes.

It’s a big neighborhood, Mother says. Why would we know her janitor? White people think Negroes all know each other, and they always want you to know their janitor. Do they want to know our laundryman?

That would be Wally, a smiling, big-shouldered white man who delivered crisply wrapped shirts and cheerful greetings to our back door every week.

Good morning, Mrs. Jefferson, he’d say. Morning, Doctor. Hello, girls.

Hello, Wally, we’d chime back from the breakfast table. Then, one afternoon, I was in the kitchen with Mother doing something minor and domestic like helping unpack groceries, when she said slowly, not looking at me: I saw Wally at Sears today. I was looking at vacuum cleaners. And I looked up and saw him—here she paused for a moment of Rodgers and Hammerstein irony—across a crowded room. He was turning his head away, hoping he wouldn’t have to speak. Wally the laundryman was trying to cut me. She made a small “hmmm” sound, a sound of futile disdain. I don’t even shop at Sears except for appliances.

Langston Hughes said, Humor is laughing at what you haven’t got when you ought to have it—the right, in this case, to snub or choose to speak kindly to your laundryman in a store where he must shop for clothes and you shop only for appliances.

Still, Wally went on delivering laundry with cheerful deference, and we responded with cool civility. Was there no Negro laundry to do Daddy’s shirts as well or better? Our milkman was a Negro. So was our janitor, our plumber, our carpenter, our upholsterer, our caterer, and our seamstress. Though I don’t remember all their names, I know their affect was restful. Comfortable.

If, perchance, a Negro employee did his work in a sloppy or sullen way (and it did happen), Mother and Daddy had two responses. One was a period wisecrack along the lines of: Well, some of us are lazy, quiet as it’s kept. Humor is laughing at what you haven’t got when you ought to have it: in this case a spotless race reputation.

The second was somber and ominously layered: Some Negroes would rather work for white people. They don’t resent their status in the same way.

Let’s unpack that. Let’s say you are a Negro cleaning woman, on your knees at this minute, scrubbing the bathtub with its extremely visible ring of body dirt, because whoever bathed last night thought: How nice. I don’t have to clean the tub because Cleo/Melba/Mrs. Jenkins comes tomorrow! Tub done, you check behind the toilet (a washcloth has definitely fallen back there); the towels are scrunched, not hung on the racks, and you’ve just come from the children’s bedroom where sheets will have to be untangled and almost throttled into shape before they can be sorted for the wash. Cleo/Melba/Mrs. Jenkins will do that.

Would you rather look at the people you do all that for and think: If the future of this country is anything like its past I will never be able to have what these white people have, or would you rather look at them and think: Well, if I’d had the chance to get an education like Dr. and Mrs. Jefferson did, if I hadn’t had to start doing housework at fifteen to help my family out when we moved up here from Mississippi, then maybe I could be where they are.

Whose privilege would you find more bearable?

Who are “you”? How does your sociological vita—race or ethnicity, class, gender, family history—affect your answer?

Whoever you are, reader, please understand this: never did my parents, my sister, or I leave a dirty bathtub for Mrs. Blake to clean. (My sister and I called her Mrs. Blake. Mother called her Blake.) She was broad, not fat. She had very short, very straightened hair that she patted flat and put behind her ears. When it got humid in the basement, where the washer and dryer were, or in the room where she ironed clothes, short pieces of hair would defy hot comb and oil to stick up. My sister and I never made direct fun of her hair—Mother would have punished our rudeness—but we did find many occasions to mock Negro hair that blatantly defied rehabilitation. We used hot combs and oil, but more discreetly. And our hair was longer.

Mother made clear that we were never to leave our beds unmade when Mrs. Blake was coming. She was not there to pick up after us.

Mrs. B’s voice was Southern South Side: leisurely and nasal. Now that I’ve given my adult attention to the classic blues singers, I can say she had the weighted country diction of Ma Rainey and the short nasal tones of Sippie Wallace. Vowels rubbed down, end-word consonants dropped or muffled.

Mother made clear that we were never to leave our beds unmade when Mrs. Blake was coming. She was not there to pick up after us. When we were old enough, we stripped our own beds each week and folded the linen before putting it in the hamper for her to remove and wash.

Mother’s paternal grandmother, great-aunt, and aunt had been in service, so she was sensitive to inappropriate childish presumption.

Mrs. Blake ate her lunch (a hot lunch which Mother made from dinner leftovers) in the kitchen. When her day was done, Mr. Blake and their daughters drove to our house. He sent his daughters to the front door to pick her up. They had the same initials we did. Mildred and Diane. Margo and Denise. Mother brought us to the front door to exchange hellos with them. Sometimes Mrs. Blake left carrying one or two bags of neatly folded clothes. What did Mildred and Diane think as they unfolded, studied, and fit themselves into our used ensembles and separates?

Why do you want to know? Mother answers.

I want to know because I’ve spent two weeks as a Potawatami tribe member at the Palos Park summer camp in the Forest Preserves of Cook County, Illinois, being led down foot and bridle paths, sharing space with deer, birds, amphibians, and small mammals, wearing moccasins and woven feathered headbands at nighttime campfires.

According to an official history of Palos Park Village, Indians “roamed the hills” there in the eighteenth century, along with French explorers, traders, and soldiers, but the first white man to “settle” Palos was James Paddock, in 1834. Now, some 120 years later, Denise and Margo Jefferson have become two of the first Negro girls to attend the Palos Park camp alongside the descendants of white settlers.

And one of those descendants had asked if I had Indian blood. When I said I didn’t know whether I did or not, she scanned my face and said: You must. Ask your mother when she comes to pick you up.

On the last day of camp the little descendant stood beside me as Mother emerged from her car. Cotton piqué rose-and-white-striped dress. Light brown skin. A Claudette Colbert cap of dark hair. Beneath her black sunglasses a hooked nose asserted itself. The little descendant turned to me, nodded, and whispered: I told you you have Indian blood. Ask your mother on the way home.

Why should this be information I’m denied? It would be exciting to be something other than just Negro. I wait till we get home, till Denise and I have made our way through talk of cabin mates and counselors, hikes and canoe trips, through the success, achieved once more, by our normality. Then I ask my question and Mother sighs.

Here was an unexpected similarity between Negroes and whites: the slightly desperate need to believe we had Indian blood, or at least recreational kinship rights.

Yee-sss (drawn out to telegraph reluctance), we do have some Indian blood. But I get so tired of Negroes always talking about their Indian blood. And so tired of white people always asking about it. Here was an unexpected similarity between Negroes and whites: the slightly desperate need to believe we had Indian blood, or at least recreational kinship rights.

And the next summer a full-blooded Indian comes to camp. Denise and I take her up, enjoying her sweet manner and her dark, shining waist-length braids. Mysteriously, on the last day, no one arrives to take her home. We volunteer our mother.

Lanova gets into the back seat with us and tells Mother where she lives. The three of us grow quiet as Mother drives, drives, and drives. Finally we arrive at a shabby group of apartment buildings. No trees, no trimmed shrubbery. We don’t hug, but we say goodbye till next summer. Lanova gets out of the car, turns, and walks toward one of the big ugly housing project buildings. She has on a rust-colored shirt and the same jeans she’s worn every day at camp. Mother starts the car and speeds away. None of us says anything about Lanova. Do you know what tribe she really belonged to? I ask Denise that night when we’re alone in our room. She doesn’t answer.

The next summer no recognizable Indian appears at Palos Park. Another Negro does, though. Ronnie arrives a few days after the rest of the campers. He’s in my age group, he’s a little bit chubby and he wears glasses, though not as thick as mine. He’s definitely browner than I am, by several shades. He’s dark brown. I notice how carefully his blue jean cuffs are rolled—folded up and ironed—and how just-from-the-package his navy and white t-shirt looks with its crisp, three-button collar. I know he has bad hair because it’s been shaved so close to his scalp.

At the end of the week my counselor takes me aside. Can I help Ronnie fit in better, she wants to know, can I talk to him? Everyone is still calling him the New Kid. I’m mortified. I hate it when I’m supposed to be enjoying myself and Race singles me out for special chores. I will, I tell her, making myself sound agreeable. And I do. I can see the two of us even now, Ronnie and me, making trite, labored conversation. Neither of us smiling.

After that he leaves my memory. We had no more encounters. But here’s something I still want to know: Why wasn’t Phillip asked to talk to Ronnie? Because Phillip was a Negro too, Phillip was the other Negro at camp and he was a boy; he should have been asked to talk to Ronnie. Phillip was my friend; our parents were close friends. Phillip had Negro hair, but it was curly-frizzy hair no one would mind touching. Phillip had pale olive skin and crisp, neatly tailored features.

I feel a surge of grief when I think of Ronnie. And inside that grief is guilt, because I looked down on him.

Phillip should have been asked to talk to Ronnie! I exclaim when I tell the story to a white friend fifty-eight years later.

The counselors didn’t read Phillip as Negro, my white friend answers. She’s seen a picture of us standing with our mothers in Washington Park. Phillip settled into the landscape of whiteness.

Yes. Of course. We map it out. The counselors might have thought Phillip was half-white: his mother was clearly a Negro, but his father was often taken for a white man. Even if they’d only seen his mother, they would have decided that it was more appropriate, that Ronnie would be more comfortable talking to someone who looked more like him.

I feel a surge of grief when I think of Ronnie. And inside that grief is guilt, because I looked down on him, and shame, because “looked down on him” is accurate, but not sufficient.

I dreaded him.

—If, as was said, too many of us ached, longed, strove to be be be be White White White White WHITE;

—If (as was said) many us boasted overmuch of the blood des blancs which for centuries had found blatant or surreptitious ways to flow, course, and trickle tepidly through our veins;

—If we placed too high a value on the looks, manners, and morals of the Anglo-Saxon…

…White people did too. They wanted to believe they were the best any civilization could produce. They wanted to be white just as much as we did. They worked just as hard at it. They failed just as often. But they could pass so no one objected.

Caucasian privilege lounged and sauntered, draped itself casually about, turned vigilant and commanding, then cunning and devious. We marveled at its tonal range, its variety, its largesse in letting its most humble share the pleasures of caste with its mighty. We knew what was expected of us. Negro privilege had to be circumspect: impeccable but not arrogant; confident yet obliging; dignified, not intrusive.

Early summer, 1956.

Two Negro parents and two Negro daughters stand at a hotel desk in Atlantic City. This is the last stop on their road trip after Montreal, Quebec City, and New York: the plan is to lounge on the beach and stroll the boardwalk. It’s midday, and guests saunter through the lobby in resort wear. The Caucasian clerk in his brown uniform studies the reservation book, looking puzzled as he traces the list with his finger.

You said Mr. and Mrs. Jefferson…

Dr. and Mrs. Jefferson, says my father.

The clerk turns the page, studies the list, again, running his eyes and his index finger slowly up and down. Just before he turns it back again, he stops.

Oh, here you are, Doc. The hotel is so crowded this week. We had to change your room.

Trailing my sister and me, our parents follow the uniformed bellboy into the elevator. It stops a few floors up, they get out, he leads them to the end of a long hall then around a corner, unlocks the door and puts their suitcases just inside a small room, leading into another small room. We’re looking out on a parking lot.

Our mother has said that a lot of white people don’t like to call Negroes “Doctor.”

When the bellboy leaves, my father goes into the larger small room without saying anything. My sister and I had stopped talking when the clerk’s finger reached the bottom of the first page.

Unpack your towels and swimsuits, our mother orders. Read or play quietly till we go to the beach. She follows my father into the other room and shuts the door.

We unpack quickly so she won’t be annoyed when she comes back. Just what is going on? All the other hotels had our reservations. Our mother has said that a lot of white people don’t like to call Negroes “Doctor.”

At the beach the girls settle on their new beach towels and fondle the sand. Dr. and Mrs. Jefferson sit on their own blanket talking in low voices. My mother never swims, but my father loves to. Today, though, he takes us to the water’s edge and watches us go in and come out.

It’s getting cooler, it’s late afternoon: time to fold the towels neatly, put them in the beach bag, and return to the hotel. Take your baths, Mother says, but only after she has taken a hotel facecloth and soap bar to the lines on the bottom of the tub that don’t wash away.

Where are we going for dinner? I ask. What should we wear?

We’re eating here, Mother answers.

We want to eat in the hotel dining room.

We’re ordering room service and eating here, Mother says in her implacable voice. And we’re leaving tomorrow.

Denise speaks up for us both.

We just got here. We didn’t get to stay long at the beach. Why can’t we eat in the hotel dining room?

We resent the bad mood that has come over our parents. We want the beach and we want the boardwalk we’ve been promised since the trip began.

Mother pauses, then addresses us and herself. This is a prejudiced place. What kind of service would we get in that restaurant? Look at these shabby rooms. Pretending they couldn’t find the reservation. We’re leaving tomorrow. And your father will tell them why.

My father has not smiled since the four of us walked into the lobby and stood at the desk waiting as the clerk turned us into Mr. and Mrs. Negro Nobody with their Negro children from somewhere in Niggerland.

We drive back to Chicago, an American family returning home from the kind of vacation successful American families have.

The next morning Denise and I are told to sit on the lobby couch while our parents check out; we don’t hear what our father says, if he says anything.

We drive back to Chicago, an American family returning home from the kind of vacation successful American families have. We’d stayed at the Statler Hilton in New York and eaten in their restaurant. We’d pummeled and pounced on the bolsters of the Chateau Frontenac in Quebec. When Daddy asked strangers in Montreal for directions, their answers were always accurate and polite. Only Atlantic City went wrong. In the car our parents reproach themselves for not doing more research, consulting friends on the East Coast before taking the risk.

Such treatment encouraged privileged Negroes to see our privilege as hard-won and politically righteous, a boon to the race, a source of compensatory pride, an example of what might be achieved. Back in the privacy of an all-Negro world, Negro privilege could lounge and saunter too, show off its accoutrements and lay down the law. Regularly denounce Caucasians, whose behavior toward us, and all dark-skinned people, proved they did not morally deserve their privilege. We had the moral advantage; they had the assault weapons of “great civilization” and “triumphant history.” Ceaselessly, we chronicled our people’s achievements. Ceaselessly we denounced our people’s failures.

Too many of us just aren’t trying. No ambition. No interest in education. You don’t have to turn your neighborhood into a slum just because you’re poor. Negroes like that made it hard for the rest of us. They held us back. We got punished for their bad behavior.

1956, a month after our trip.

Professionals and small businessmen live on one end of our block. A cabdriver and his wife, a nurse, live at the midpoint next door to us. I play often with their daughter Shirley. At the other end of the block is Betty Ann, somebody’s daughter, we don’t know whose. She has lots of short braids on her head, fastened with red, yellow, and green plastic barrettes. She wears red nail polish and keeps it on till it’s nothing but tiny chips. I beg to be allowed to wear red nail polish outside, and not just when I dress up in mother’s old clothes. No, comes the answer, red nail polish on children is cheap.

In the summer Betty Ann saunters up and down the block letting the backs of her shoes flap against her heels. When she finds something ridiculous she folds her arms and goes oooo-oooo-OOO, Uh-un-UNNHH. When she laughs she bends over at the waist and shuffles her feet. Denise and I start to do this at home. Where did you pick that up, our mother asks. Don’t collapse all over yourself when you laugh.

One afternoon we see Betty Ann playing Double Dutch with two girls we’ve never met. They laugh a lot and say “Girrlll…” Then they start to turn the ropes.

Betty Ann’s the jumper. She leans in, arms bent, fists balled, gauging her point of entry. Turn slap turn slap turn slap and there she goes! Her knees pump, her feet quick-slap the ground, parrying the ropes till, fleet of foot and neat, she jumps out. Rapt and envious, we watch them take turns. Betty Ann doesn’t come down to play jacks with us or borrow Denise’s bike. She and her friends laugh and eat candy, and jump Double Dutch. After a week of this we stroll down the block hoping they’ll ask us to join. After a few days they do. Denise isn’t good but she’s not bad: she swings correctly and manages a few solid intervals before the ropes catch her. My swinging isn’t fast or steady enough, and the ropes reject my anxious feet in seconds. By the time I clamor for a third try, Betty Ann and her friends say No.

It’s not the No I remember; it’s their snickering scorn. I’m used to being the youngest and clumsiest when I play with Denise’s friends, but if one of them mocks or reproves me, another pets me to make up for it. If they act too badly, their mothers intervene. Or Denise does, and after a short quarrel and apology they resume play.

Not now. Betty Ann’s Ooo ooh ooooo, Un-un-unhhhh is definitive. Denise raises her voice: We have to go home now. Betty Ann and her friends laugh a little harder. Denise sets a slow pace, as if we’re leaving by choice. My father and uncle are waiting in front of the apartment: they’ve heard the laughter and looked down the block to see us in shamed, haughty retreat. I bask in their sympathy.

Over dinner the adults concur: we will never play with Betty Ann again. She and her friends are loud and coarse. They envy you girls.

Of course they envy us. Now I remember, now I can repeat to myself all the things I’ve heard my parents say about Betty Ann. Where are her mother and father? What kind of work do they do? Have you noticed how unkempt their end of the block looks?

We moved to this neighborhood just five years ago, my father says gravely. We may need to move again, soon.